Hypertension Despite Dehydration in an Adolescent with Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.L1114 on 29 May 2019

STATE OF THE ART REVIEW Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.l1114 on 29 May 2019. Downloaded from hyperglycemic syndrome: review of acute decompensated diabetes in adult patients Esra Karslioglu French,1 Amy C Donihi,2 Mary T Korytkowski1 1Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of ABSTRACT Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome (HHS) are life threatening 2University of Pittsburgh School of complications that occur in patients with diabetes. In addition to timely identification of the Pharmacy, Pittsburgh, PA, USA Correspondence to: M Korytkowski precipitating cause, the first step in acute management of these disorders includes aggressive [email protected] administration of intravenous fluids with appropriate replacement of electrolytes (primarily Cite this as: BMJ 2019;365:l1114 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1114 potassium). In patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, this is always followed by administration Series explanation: State of the of insulin, usually via an intravenous insulin infusion that is continued until resolution of Art Reviews are commissioned on the basis of their relevance to ketonemia, but potentially via the subcutaneous route in mild cases. Careful monitoring academics and specialists in the US and internationally. For this reason by experienced physicians is needed during treatment for diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS. they are written predominantly by Common pitfalls in management include premature termination of intravenous insulin US authors therapy and insufficient timing or dosing of subcutaneous insulin before discontinuation of intravenous insulin. This review covers recommendations for acute management of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, the complications associated with these disorders, and methods for http://www.bmj.com/ preventing recurrence. -

Persistent Lactic Acidosis - Think Beyond Sepsis Emily Pallister1* and Thogulava Kannan2

ISSN: 2377-4630 Pallister and Kannan. Int J Anesthetic Anesthesiol 2019, 6:094 DOI: 10.23937/2377-4630/1410094 Volume 6 | Issue 3 International Journal of Open Access Anesthetics and Anesthesiology CASE REPORT Persistent Lactic Acidosis - Think beyond Sepsis Emily Pallister1* and Thogulava Kannan2 1 Check for ST5 Anaesthetics, University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire, UK updates 2Consultant Anaesthetist, George Eliot Hospital, Nuneaton, UK *Corresponding author: Emily Pallister, ST5 Anaesthetics, University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire, Coventry, UK Introduction • Differential diagnoses for hyperlactatemia beyond sepsis. A 79-year-old patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for manage- • Remember to check ketones in patients taking ment of Acute Kidney Injury refractory to fluid resusci- Metformin who present with renal impairment. tation. She had felt unwell for three days with poor oral • Recovery can be protracted despite haemofiltration. intake. Admission bloods showed severe lactic acidosis and Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). • Suspect digoxin toxicity in patients on warfarin with acute kidney injury, who develop cardiac manifes- The patient was initially managed with fluid resus- tations. citation in A&E, but there was no improvement in her acid/base balance or AKI. The Intensive Care team were Case Description asked to review the patient and she was subsequently The patient presented to the Emergency Depart- admitted to ICU for planned haemofiltration. ment with a 3 day history of feeling unwell with poor This case presented multiple complex concurrent oral intake. On examination, her heart rate was 48 with issues. Despite haemofiltration, acidosis persisted for blood pressure 139/32. -

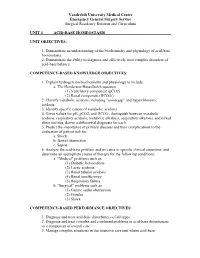

Unit 4 Acid-Base Homeostasis

Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum UNIT 4 ACID-BASE HOMEOSTASIS UNIT OBJECTIVES: 1. Demonstrate an understanding of the biochemistry and physiology of acid-base homeostasis. 2. Demonstrate the ability to diagnose and effectively treat complex disorders of acid-base balance. COMPETENCY-BASED KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES: 1. Explain hydrogen ion biochemistry and physiology to include: a. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation (1) Ventilatory component (pCO2) (2) Renal component (HCO3-) 2. Classify metabolic acidosis, including "anion gap" and hyperchloremic acidosis. 3. Identify specific causes of metabolic acidosis. 4. Given values for pH, pCO2, and HCO3-, distinguish between metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, metabolic alkalosis, respiratory alkalosis, and mixed abnormalities; derive a differential diagnosis for each. 5. Predict the importance of primary diseases and their complications to the evaluation of patient risk for: a. Shock b. Bowel obstruction c. Sepsis 6. Analyze the acid-base problem and its cause in specific clinical situations, and determine an appropriate course of therapy for the following conditions: a. "Medical" problems such as: (1) Diabetic ketoacidosis (2) Lactic acidosis (3) Renal tubular acidosis (4) Renal insufficiency (5) Respiratory failure b. "Surgical" problems such as: (1) Gastric outlet obstruction (2) Fistulas (3) Shock COMPETENCY-BASED PERFORMANCE OBJECTIVES: 1. Diagnose and treat acid-base disturbances of all types. 2. Diagnose and treat complex and combined problems in acid-base disturbances as a component of overall care. 3. Manage complex situations in the intensive care unit where acid-base Vanderbilt University Medical Center Emergency General Surgery Service Surgical Residency Rotation and Curriculum abnormalities coexist with other metabolic derangements, including: a. -

Lecture-1 Keto Acidosis, Bovine Ketosis, Ovine Pregnancy Toxemia

Lecture-1 Keto acidosis Ketoacidosis is a metabolic acidosis due to an excessive blood concentration of ketone bodies (acetone, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate). Ketone bodies are released into the blood from the liver when hepatic lipid metabolism has changed to a state of increased ketogenesis. The abnormal accumulation of ketones in the body occurs due to excessive breakdown of fats in deficiency or inadequate use of carbohydrates. It is characterized by ketonuria, loss of potassium in the urine, and a fruity odor of acetone on the breath. Untreated, ketosis may progress to ketoacidosis, coma, and death. This condition is seen in starvation, occasionally in pregnancy if the intake of protein and carbohydrates is inadequate, and most frequently in diabetes mellitus. Different Types of Ketoacidosis Diabetes Keto Acidosis (DKA): Due to lack of insulin glucose uptake and metabolism by cells is decrased.Fatty acid catabolism increased in resulting in excess production of ketone bodies. Starvation Ketosis: Starvation leads to hypoglycemia as there is little or no absorption of glucose from intestine and also due to depletion of liver glycogen. In Fatty acid oxidation leads to excess ketone body. Bovine Ketosis Introduction Bovine ketosis occurs in the high producing dairy cows during the early stages of lactation, when the milk production is generally the highest. Abnormally high levels of the ketone bodies, acetone, acetoacetic and beta-hydroxy butyric acid and also iso- propanol appear in blood, urine and in milk. The alterations are accompanied by loss of appetite , weight loss, decrease in milk production and nervous disturbances. Hypoglycemia (starvation) is a common finding in bovine ketosis and in ovine pregnancy toxemia. -

Diabetic Ketoalkalosis in Children and Adults

Original Article Diabetic Ketoalkalosis in Children and Adults Emily A. Huggins, MD, Shawn A. Chillag, MD, Ali A. Rizvi, MD, Robert R. Moran, PhD, and Martin W. Durkin, MD, MPH and DR are calculated because the pH and bicarbonate may be near Objectives: Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) with metabolic alkalosis normal or even elevated. In addition to having interesting biochemical (diabetic ketoalkalosis [DKALK]) in adults has been described in the features as a complex acid-base disorder, DKALK can pose diagnostic literature, but not in the pediatric population. The discordance in the and/or therapeutic challenges. change in the anion gap (AG) and the bicarbonate is depicted by an Key Words: delta ratio, diabetic ketoacidosis, diabetic ketoalkalosis, elevated delta ratio (DR; rise in AG/drop in bicarbonate), which is metabolic alkalosis normally approximately 1. The primary aim of this study was to de- termine whether DKALK occurs in the pediatric population, as has been seen previously in the adult population. The secondary aim was iabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a common and serious dis- to determine the factors that may be associated with DKALK. Dorder that almost always results in hospitalization, is de- Methods: A retrospective analysis of adult and pediatric cases with a fined by the presence of hyperglycemia, reduced pH, metabolic 1 primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of DKA between May 2008 and acidosis, elevated anion gap (AG), and serum or urine ketones. August 2010 at a large urban hospital was performed. DKALK was as- In some situations, a metabolic alkalosis coexists with DKA sumedtobepresentiftheDRwas91.2 or in cases of elevated bicarbonate. -

Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Evaluation and Treatment DYANNE P

Diabetic Ketoacidosis: Evaluation and Treatment DYANNE P. WESTERBERG, DO, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey Diabetic ketoacidosis is characterized by a serum glucose level greater than 250 mg per dL, a pH less than 7.3, a serum bicarbonate level less than 18 mEq per L, an elevated serum ketone level, and dehydration. Insulin deficiency is the main precipitating factor. Diabetic ketoacidosis can occur in persons of all ages, with 14 percent of cases occurring in persons older than 70 years, 23 percent in persons 51 to 70 years of age, 27 percent in persons 30 to 50 years of age, and 36 percent in persons younger than 30 years. The case fatality rate is 1 to 5 percent. About one-third of all cases are in persons without a history of diabetes mellitus. Common symptoms include polyuria with polydipsia (98 percent), weight loss (81 percent), fatigue (62 percent), dyspnea (57 percent), vomiting (46 percent), preceding febrile illness (40 percent), abdominal pain (32 percent), and polyphagia (23 percent). Measurement of A1C, blood urea nitro- gen, creatinine, serum glucose, electrolytes, pH, and serum ketones; complete blood count; urinalysis; electrocar- diography; and calculation of anion gap and osmolar gap can differentiate diabetic ketoacidosis from hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, gastroenteritis, starvation ketosis, and other metabolic syndromes, and can assist in diagnosing comorbid conditions. Appropriate treatment includes administering intravenous fluids and insulin, and monitoring glucose and electrolyte levels. Cerebral edema is a rare but severe complication that occurs predominantly in chil- dren. Physicians should recognize the signs of diabetic ketoacidosis for prompt diagnosis, and identify early symp- toms to prevent it. -

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) Is a Serious Problem That Can Happen in People with Diabetes

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a serious problem that can happen in people with diabetes. DKA should be treated as a medical emergency. This is because it can lead to coma or death. If you have the symptoms of DKA, get medical help right away. DKA happens more often in people with type 1 diabetes. But it can happen in people with type 2 diabetes. It can also happen in women with diabetes during pregnancy (gestational diabetes). DKA happens when insulin levels are too low. Without enough insulin, sugar (glucose) can’t get to the cells of your body. The glucose stays in the blood. The liver then puts out even more glucose into the blood. This causes high blood glucose (hyperglycemia). Without glucose, your body breaks down stored fat for energy. When this happens, acids called ketones are released into the blood. This is called ketosis. High levels of ketones (ketoacidosis) can be harmful to you. Hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis can also cause serious problems in the blood and your body, such as: • Low levels of potassium (hypokalemia) and phosphate • Damage to kidneys or other organs • Coma What causes diabetic ketoacidosis? In people with diabetes, DKA is most often caused by too little insulin in the body. It is also caused by: • Poor management of diabetes • Infections such as a urinary tract infection or pneumonia • Serious health problems, such as a heart attack • Reactions to certain prescribed medicines including SGLT2 inhibitors for treating type 2 diabetes • Reactions to illegal drugs including cocaine • Disruption of insulin delivery from an insulin pump Symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis DKA most often happens slowly over time. -

Observations Compensatory Hypochloraemic Alkalosis In

Letters 871 tended to the DQ-LTR13 integration, where we also find a con- 2. Pascual M, Martin J, Nieto A et al. (2001) Distribution of tribution of DQ-LTR13 to RA susceptibility in DQ8-positive HERV-LTR elements in the 5′-flanking region of HLA- individuals. Furthermore we recently published that patients DQB1 and association with autoimmunity. Immunogenetics with Addison’s disease—another HLA DQ8-associated autoim- 53:114–118 mune disease of the adrenals which may occur in combination 3. Donner H, Tonjes RR, Bontrop RE et al. (1999) Intronic se- with Type 1 diabetes as part of the autoimmune pluriglandular quence motifs of HLA-DQB1 are shared between humans, syndrome Type 2—have more often the DQ8-DQ-LTR13 com- apes and Old World monkeys, but a retroviral LTR element bination in contrast to the DQ-LTR3 insertion. Although both (DQLTR3) is human specific. Tissue Antigens 53:551–558 DQ-LTR3 and DQ-LTR13 are linked to DQ8, DQ-LTR13 en- 4. Donner H, Tonjes RR, Van der Auwera B et al. (1999) The hances the risk for Addison’s disease [7]. presence or absence of a retroviral long terminal repeat Whether DQ-LTR13 has a functional significance or not is influences the genetic risk for type 1 diabetes conferred by currently under investigation. Preliminary data indicate that human leukocyte antigen DQ haplotypes. J Clin Endocrinol DQ-LTR13 harbours regulatory capacity and shows functional Metab 84:1404–1408 activity of an upstream element as revealed by analyses of nu- 5. Seidl C, Donner H, Petershofen E et al. -

ACS/ASE Medical Student Core Curriculum Acid-Base Balance

ACS/ASE Medical Student Core Curriculum Acid-Base Balance ACID-BASE BALANCE Epidemiology/Pathophysiology Understanding the physiology of acid-base homeostasis is important to the surgeon. The two acid-base buffer systems in the human body are the metabolic system (kidneys) and the respiratory system (lungs). The simultaneous equilibrium reactions that take place to maintain normal acid-base balance are: H" HCO* ↔ H CO ↔ H O l CO g To classify the type of disturbance, a blood gas (preferably arterial) and basic metabolic panel must be obtained. A basic understanding of normal acid-base buffer physiology is required to understand alterations in these labs. The normal pH of human blood is 7.40 (7.35-7.45). This number is tightly regulated by the two buffer systems mentioned above. The lungs contain carbonic anhydrase which is capable of converting carbonic acid to water and CO2. The respiratory response results in an alteration to ventilation which allows acid to be retained or expelled as CO2. Therefore, bradypnea will result in respiratory acidosis while tachypnea will result in respiratory alkalosis. The respiratory buffer system is fast acting, resulting in respiratory compensation within 30 minutes and taking approximately 12 to 24 hours to reach equilibrium. The renal metabolic response results in alterations in bicarbonate excretion. This system is more time consuming and can typically takes at least three to five days to reach equilibrium. Five primary classifications of acid-base imbalance: • Metabolic acidosis • Metabolic alkalosis • Respiratory acidosis • Respiratory alkalosis • Mixed acid-base disturbance It is important to remember that more than one of the above processes can be present in a patient at any given time. -

Ketogenesis & Ketone Bodies

THE METABOLISM OF KETONE BODIES KETOGENESIS CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF KETOGENESIS • The production of ketone bodies occurs at a relatively low rate during normal feeding and under conditions of normal physiological status. • Normal physiological responses to carbohydrate shortages cause the liver to increase the production of ketone bodies from the acetyl-CoA generated from fatty acid oxidation. This allows the heart and skeletal muscles primarily to use ketone bodies for energy, thereby preserving the limited glucose for use by the brain. • The most significant disruption in the level of ketosis, leading to profound clinical manifestations, occurs in untreated insulin- dependent diabetes mellitus. This physiological state, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), results from a reduced supply of glucose (due to a significant decline in circulating insulin) and a concomitant increase in fatty acid oxidation (due to a concomitant increase in circulating glucagon). • The increased production of acetyl-CoA leads to ketone body production that exceeds the ability of peripheral tissues to oxidize them. • Ketone bodies are relatively strong acids (pKa around 3.5), and their increase lowers the pH of the blood. This acidification of the blood is dangerous chiefly because it impairs the ability of hemoglobin to bind oxygen. • It is important to note that animals are unable to convert fatty acids into glucose. • Specifically, acetyl CoA cannot be converted into pyruvate or oxaloacetate in animals. • The two carbon atoms of the acetyl group of acetyl CoA enter the citric acid cycle, but two carbon atoms leave the cycle in the decarboxylations catalyzed by isocitrate dehydrogenase and a-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. • Consequently, oxaloacetate is regenerated but it is not formed de novo when the acetyl unit of acetyl CoA is oxidized by the citric acid cycle. -

The Accuracy of Clinical Assessment of Dehydration During Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Childhood

BRIEF REPORT The Accuracy of Clinical Assessment of Dehydration During Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Childhood 1 1 ILDIKO H. KOVES, MD GEORGE A. WERTHER, MD hydration categories as those used for the 2 2 JOCELYN NEUTZE, MD PETER BARNETT, MD doctors’ assessments. 3 1 SUSAN DONATH, MA FERGUS J. CAMERON, MD 1 WARREN LEE, MD Statistical analysis Agreement between the doctor’s assess- ments of dehydration and between as- sessed and measured dehydration were Ͻ he objective of this study was to ex- were pH 7.30 (capillary, venous, or ar- evaluated using -statistics (5). amine the accuracy of the assess- terial) and/or bicarbonate Ͻ15 mmol/l T ment of clinical dehydration in and ketones in the urine on dipstick test- children with type 1 diabetes and diabetic ing. The following information was re- RESULTS — The greatest number of ketoacidosis (DKA). DKA remains the sin- corded by the primary assessing doctor: patients (18 of 37) were between 5 and gle most common cause of diabetes- newly diagnosed or established diabetes, 10% dehydrated at presentation (as related death in childhood (1). Accurate age, sex, date and time seen, heart rate, calculated by their weight gains), with assessment and management of dehydra- respiratory rate, blood pressure, pale a median absolute measure of 8.7% tion is the cornerstone of DKA treatment and/or cool hands and feet, peripheral dehydration. (1,2). The assessment of the degree of capillary refill time, reduced skin turgor, There was a good level of agreement dehydration has traditionally been ac- level of consciousness (on a rating scale of between the primary and secondary as- cording to clinical criteria including pe- one to eight), sunken eyes, sunken fonta- sessor (ϭ0.5). -

Fluid Management in Diabetic Ketoacidosis

CONTROVERSY 443 General paediatrics case controlled studies of cerebral Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.86.6.443 on 1 June 2002. Downloaded from ................................................................................... oedema complicating DKA and there is conflicting evidence as to the role of iatrogenic factors in fatal cases.613How- Fluid management in diabetic ever, excessive rates of fluid administra- tion, particularly early in resuscitaion,14 ketoacidosis and failure of plasma sodium to rise as plasma glucose declines, have been iden- C D Inward, T L Chambers tified as risk factors. Studies using computed tomography ................................................................................... suggest that subclinical cerebral swelling Have we got it right yet? may be a common occurrence in children presenting with DKA,15 16 although this has been disputed.17 If cerebral swelling oung people with insulin depend- may be considered and treated as a vari- is a relatively common event it is not ent diabetes mellitus are three ant of renal electrolyte disorder with clear why only a minority progress to times more likely to die in child- hypertonic dehydration. herniation. In addition, fatal herniation Y 1 hood than the general population. De- has occurred in the absence of any fluid spite advances in management over the FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE LOSSES therapy. Therefore, although clearly not past 20 years, the incidence of mortality The fluid and electrolyte losses of DKA the only cause, it seems reasonable to associated with diabetic ketoacidosis are predominantly caused by hypergly- conclude that fluid management may be (DKA) remains unchanged. Cerebral caemia with resultant glycosuria and a factor contributing to the development oedema is the predominant cause of this osmotic diuresis.