The Law of Look and Feel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 1998 A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager Scott .J Griswold University of North Florida Suggested Citation Griswold, Scott .,J "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" (1998). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 95. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/95 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 1998 All Rights Reserved A JAVA IMPLEMENTATION OF A PORTABLE DESKTOP MANAGER by Scott J. Griswold A thesis submitted to the Department of Computer and Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCES April, 1998 The thesis "A Java Implementation of a Portable Desktop Manager" submitted by Scott J. Griswold in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer and Information Sciences has been ee Date APpr Signature Deleted Dr. Ralph Butler Thesis Advisor and Committee Chairperson Signature Deleted Dr. Yap S. Chua Signature Deleted Accepted for the Department of Computer and Information Sciences Signature Deleted i/2-{/1~ Dr. Charles N. Winton Chairperson of the Department Accepted for the College of Computing Sciences and E Signature Deleted Dr. Charles N. Winton Acting Dean of the College Accepted for the University: Signature Deleted Dr. -

LWUIT Developer's Guide

Lightweight UI Toolkit Developer’s Guide Part No. 07-08-10 July 2010 Copyright © 2008, 2010 Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related software documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT RIGHTS Programs, software, databases, and related documentation and technical data delivered to U.S. Government customers are "commercial computer software" or "commercial technical data" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency-specific supplemental regulations. As such, the use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation shall be subject to the restrictions and license terms set forth in the applicable Government contract, and, to the extent applicable by the terms of the Government contract, the additional rights set forth in FAR 52.227-19, Commercial Computer Software License (December 2007). Oracle America, Inc., 500 Oracle Parkway, Redwood City, CA 94065. -

UI Manager Properties

APPENDIX A UI Manager Properties THROUGHOUT THIS BOOK YOU'LL FIND TABLES that list the property names and data types for all the UIResource elements of specific Swing components. Although these tables serve to list all the information about a specific component, I fig ured it would be handy to also group all the information about property names in one place. With that in mind, Table A-1 provides a complete list of properties used by the predefined look and feel classes-Motif, Macintosh, Metal, and Windows provided with the Swing 1.1.1 release. The table indicates with an "X" which of the four look and feel classes uses a particular property. To change the default setting for any one of these properties, you need to notify the UIManager by storing a new setting in the lookup table of the UIManager. For instance, to change the default text for the "Yes" button on a JOptionPane, 11 you'd replace the 0ptionPane. yesButtonText II property with the new setting 11 11 UIManager. put ( 0ptionPane. yesButtonTextll, Si II);. Then, any component cre ated after the setting change will get the new value: 11 5i 11 .1fyou want a displayed component to get the new setting, you must call its updateUI () method. When you change the current look and feel, any custom settings you install may be lost. If the class of the property value setting implements the UIResource interface (an empty marker interface such as Serializable), then the setting will be replaced by the default setting of the look and feel. -

Translate's Localization Guide

Translate’s Localization Guide Release 0.9.0 Translate Jun 26, 2020 Contents 1 Localisation Guide 1 2 Glossary 191 3 Language Information 195 i ii CHAPTER 1 Localisation Guide The general aim of this document is not to replace other well written works but to draw them together. So for instance the section on projects contains information that should help you get started and point you to the documents that are often hard to find. The section of translation should provide a general enough overview of common mistakes and pitfalls. We have found the localisation community very fragmented and hope that through this document we can bring people together and unify information that is out there but in many many different places. The one section that we feel is unique is the guide to developers – they make assumptions about localisation without fully understanding the implications, we complain but honestly there is not one place that can help give a developer and overview of what is needed from them, we hope that the developer section goes a long way to solving that issue. 1.1 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide one reference for localisers. You will find lots of information on localising and packaging on the web but not a single resource that can guide you. Most of the information is also domain specific ie it addresses KDE, Mozilla, etc. We hope that this is more general. This document also goes beyond the technical aspects of localisation which seems to be the domain of other lo- calisation documents. -

BORLAND Turbo Pascafbj Version 6.0

BORLAND Turbo PascafBJ Version 6.0 Turbo Vision Guide BORLAND INTERNATIONAL INC. 1800 GREEN HILLS ROAD P.O. BOX 660001, scons VALLEY, CA 95067-0001 Copyright © 1990 by Borland International. All rights reserved. All Borland products are trademarks or registered trademarks of Borland International, Inc. Other brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. PRINTED IN THE USA. R2 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 c o N T E N T s Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Writing Turbo Vision Why Turbo Vision? ................... 1 applications 23 What is Turbo Vision? ................. 1 Your first Turbo Vision application . .. 23 What you need to know ............... 2 The desktop, menu bar, and status line .. 25 What's in this book? ................... 2 The desktop . .. 26 The status line . .. 26 Part 1 Learning Turbo Vision Creating new commands. .. 27 Chapter 1 Inheriting the wheel 7 The menu bar ..................... 28 The framework of a windowing A note on structure . .. 30 application . .. 7 Opening a window. .. 31 A new Vision of application development. 8 Standard window equipment . .. 31 The elements of a Turbo Vision Window initialization .............. 33 application . .. 9 The Insert method ............... 33 Naming of parts .................... 9 Closing a window. .. 34 Views ........................... 9 Window behavior . .. 34 Events ........................... 9 Look through any window . .. 35 Mute objects. .. 10 What do you see? .................. 37 A common "look and feel" .......... 10 A better way to Write. .. 38 "Hello, World!" Turbo Vision style ..... 12 A simple file viewer .. .. 38 Running HELLO.PAS .............. 13 Reading a text file .. .. 39 Pulling down a menu. .. 14 Buffered drawing ................. -

Modifying Your Navigation Menu

Modifying your Navigation Menu The left side navigation pane is configured differently than your regular web site pages. You can add and remove links to your site pages, change how the menu is ordered and how the menu itself is displayed. By default, when you create a page it will show in the navigation menu. Automatically created links have icons that look like this. Manually created links have icons that look like this. note: Keep in mind that the navigation pane is designed to streamline your site and guide traffic to your web pages. If you will exceed 10 links in the left side pane, then it would be a good idea to speak with the Office of Institutional advancement and request assistance with developing the content and structure of your web site. Navigation Menu Default Settings 1.) If your navigation menu is not displaying your site links correctly, confirm it is configured correctly. Login to SharePoint, navigate to your site and click on Settings->Site settings 2.) At the next page, click on Navigation under the Look and Feel menu. 3.) In the Navigation menu, confirm that the Global Navigation and Current Navigation are set as follows. a.) Global Navigation - Select "Display the same navigation items as the parent site". b.) Current Navigation - Select "Structural Navigation: Display the navigation items below the current site". Leave the "Show Subsites" check box empty, but fill in the "Show Pages" check box. 4.) Scroll down to the "Structural Navigation" configuration. a.) Confirm the Structural Navigation: Sorting is configured to Sort manually. 5.) Scroll further down to view the actual navigation links in the Editing and Sorting window Editing Your Navigation Links New pages will automatically add themselves to the navigation menu, but you must organize the links manually. -

COPYRIGHTING "LOOK and FEEL": MANUFACTURERS TECHNOLOGIES V

Volume 3, Spring Issue, 1990 COPYRIGHTING "LOOK AND FEEL": MANUFACTURERS TECHNOLOGIES v. CAMS Brett N. Dorny* and Michael K. Friedland* INTRODUCTION Some new technologies fit easily into the preexisting legal frame- work. Immediately upon development, attorneys and courts comfortably place the technology into a familiar category. Rights are certain, trans- actions efficient, and technological progress continues unhindered. Such has not been the case with computer software,~ which, from the first, has resisted neat categorization. A programmer creates software by writing source code, a series of steps, logically arranged, containing commands similar to English words and phrases. Program source code, while distantly resembling free- flowing verse, is devoid of literary--or functional--value. In most common applications, program source code is translated into object code by a program known as a compiler. It is the object code that a computer understands. The object code, an uninterrupted series of zeros and ones, is not only uninteresting to humans, but virtually unintelligible as well. Only in the confluence of unintelligible software (object code) and com- puter hardware is a program given life, making it usable, and therefore appreciable in the marketplace. 2 Nevertheless, both source code and object code are protected by copyright, the body of law traditionally reserved for the protection of literary, cinematic, musical, and other artistic compositions. The marketability of a program depends in large part on its user inter- face. 3 In determining what software to purchase people rarely, if ever, consider the code the computer runs. Typical users are unsophisticated, and easy-to-use programs are in great demand. -

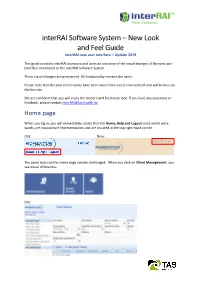

Interrai Software System – New Look and Feel Guide Interrai New User Interface – Update 2019

interRAI Software System – New Look and Feel Guide interRAI new user interface – Update 2019 This guide provides interRAI assessors and users an overview of the visual changes of the new user interface introduced to the interRAI Software System. These visual changes are permanent. All functionality remains the same. Please note that the pink screen-shots have been taken from a test environment and will be blue on the live site. We are confident that you will enjoy the modern and fresh new look. If you have any questions or feedback, please contact [email protected]. Home page When you log in, you will immediately notice that the Home, Help and Logout icons which were words, are now picture representations and are situated in the top right-hand corner. Old: New: The panel icons on the Home page remain unchanged. When you click on Client Management, you see visual differences. Old: New: Menu items are now highlighted to indicate where you are (solid dark blue highlight on the left-hand side menu) and an orange highlight will follow your mouse up and down the menu. An upper dark blue line borders the entry fields and highlights your current screen tab orange. A fine blue line displays around the field in which your cursor is sitting. The lower data field labels are also dark blue. A dark blue highlight shows when you hover your mouse over the Search and Clear Search Criteria buttons. Navigation When you enter a client record, you see visual differences on the Client Overview. The field labels are . -

EASY TEACHER WEBPAGES a Professional Development Session Presented by the Instructional Technology Department Clark County Public Schools

EASY TEACHER WEBPAGES A Professional Development Session Presented by the Instructional Technology Department Clark County Public Schools AGENDA Introduction • Web Safety • The Easy Teacher Webpage concept Set up • One-Time-Only setup process Getting Started • Resetting your Password • View your new page • Logging in to Administer Your Page • Navigating your new page: o Dashboard o Writing a post . Formatting Text . Adding hyperlinks . Adding images o Manage/Edit Posts o Creating Page Links Customization • Presentation Mode • Finding other Themes • Setting up special options Directing People to Your Site Additional Topics Time to get creative and explore your page! ONE TIME ONLY SETUP PROCEDURES These steps will only occur at the start of this session. You will never need to worry about this portion of the instructions again. STEP 1: Log into the set up page Open Internet Explorer In Address Bar type in: http://ilearn.clarkschools.net/sites/username STEP 2: Click on install.php STEP 3: Click “First Step” Continue to STEP 4 >> STEP 4: Enter basic information (this can be changed later, so don’t worry) Enter a working title Enter your Clark County email address ([email protected]) Click “Continue to Second Step” STEP 5: MOST IMPORTANT STEP – COPY YOUR ASSIGNED PASSWORD! BE SURE TO COPY THIS PASSWORD CODE. VERY IMPORTANT! Once copied, click “wp-login.php” Continue to STEP 6 >> STEP 6: Access the Administration Page for the first time The Username for everyone is “Admin” Use the password you just copied in the password box. Click Login STEP 7: Congratulations! You have just created your own webpage! The page you see on your screen is your Admin access page. -

Gnome and the Enterprise User

G N O M E A N D T H E E N T E R P R I S E U S E R Ghee S. Teo <[email protected]>, Brian Nitz <[email protected]> Sun Microsystems Inc. Abstract Sun announced the release of its Sun Java Desktop System (JDS)[tm] in late 2003 with a plan to deliver between 500,000 and 1 million copies of this desktop to China. This paper presents a behind the scenes view of the various problems faced and solutions adopted in the creation of an enterprise desktop based fundamentally on Open Source software. The primary targeted audience is project managers, engineering managers, CTO, and others who plan to distribute and contribute to Open Source Software. 1 Introduction The first section of this paper will cover the development of a GNOME desktop for enterprise users. It explores the development process as well as decisions and compromises made during this process. While it may be interesting to put together a desktop like the Sun Java Desktop System (JDS), the litmus test for the success of such an endeavor is what happens when it is deployed to real users. Therefore, in the second section we share our initial experiences in the deployment of this desktop. We will discuss lessons learned from desktop pilots within Sun and to external customers. It presents some of the problems faced by end users and discusses possible solutions. 2 Decisions Decisions The first step of the development was to choose the constituents for the complete desktop. 2.1 Choosing the base Desktop The choice of a base desktop was actually made in August 2000 when Sun chose GNOME as a replacement for the vintage CDE[tm] desktop on Solaris[tm]. -

Introduction Part 1 Learning Turbo Vision Chapter 1 Inheriting the Wheel Chapter 2 Writing Turbo Vision Applications

c o N T E N T s Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Writing Turbo Vision Why Turbo Vision? ...... ..... ...... 1 applications 23 What is Turbo Vision? ....... ..... 1 Your first Turbo Vision application .. .. 2S What you need to know . .. ... ... 2 The desktop, menu bar, and status line . 25 What's in this book? . .. ... .. ... .. .. 2 The desktop ..... ... .... .. .. " 26 ll1e status line ... .. .. ..... .... , 26 Part 1 Learning Turbo Vision Creating new commands . .. .. .... 27 Chapter 1 Inheriting the wheel 7 ll1e menu bar . ... .. .. ...... .. 28 The framework of a windowing A note on structure . .. 30 application. .. 7 Opening a window . .. 31 A new Vision of application development. 8 Standard window equipment. .. 31 The elements of a Turbo Vision Window initialization . .. .. 33 application . .. 9 The Insert method . ... .......... 33 Naming of parts ... .. .. : .... 9 Closing a window . .. 34 Views .......... .. .... .. 9 Window behavior . .. 34 Events .. .... .. .. .. .. .. 9 Look through any window . 35 Mute objects . .. 10 What do you see? ........ .. .... 37 A common "look and feel" .. ....... 10 A better way to Write .. ..... .. 38 "Hello, World!" Turbo Vision style ... 12 A simple file viewer . 38 Running HELLO.PAS . ....... .. 13 Reading a text file ... ....... .. 39 Pulling down a menu ... ..... ... 14 Buffered drawing . .. 40 A dialog box . .... ... ... ... 15 The draw buffer ...... ... ...... 40 Buttons . ..... .. ...... .. .. ..... 15 Moving text into a buffer ........ 41 Getting out . 16 Writing buffer contents ... .. .... 41 Inside HELLO.PAS .. .. .... ... ... .. 16 Knowing how much to write . ... 42 ll1e application object . .. .... ... .. 17 Scrolling up and down . ......... .. 42 ll1e dialog box object . .. .. .. .... 18 Multiple views in a window . .. 45 Flow of execution and debugging .... 19 Where to put the functionality ' " . 46 HELLO's main program. 19 Making a dialog box ... -

Composing User Interfaces with Interviews

Composing User Interfaces with InterViews Mark A. Linton, John M. Vlissides, and Paul R. Calder Center for Integrated Systems, Room 213 Stanford University Stanford, California 94305 Abstract In this article we show how to compose user interfaces with InterViews, a user interface toolkit we have developed at Stanford. InterViews provides a library of predefined objects and a set of protocols for composing them. A user interface is created by composing simple primitives in a hierarchical fashion, allowing complex user interfaces to be implemented easily. InterViews supports the composition of inter- active objects (such as scroll bars and menus), text objects (such as words and whitespace), and graphics objects (such as circles and polygons). To illustrate how InterViews composition mechanisms facilitate the implementation of user interfaces, we present three simple applications: a dialog box built from interactive objects, a drawing editor using a hierarchy of graphical objects, and a class browser using a hierarchy of text objects. We also describe how InterViews supports consistency across applications as well as end-user customization. Keywords: user interface toolkits, interactive graphics, workstation applications software. 1 Introduction Graphical user interfaces for workstation applications are inherently difficult to build without abstractions that simplify the implementation process. To help programmers create such interfaces, we considered the following questions: What sort of interfaces should be supported? What constitutes a good set of programming abstractions for building such interfaces? How does a programmer go about building an interface given these abstractions? Our efforts to develop user interface tools that address these questions have been guided by practical experience. We make the following observations: All user interfaces need not look alike.