Suicidal Ideation in the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit: Predictive Risk Markers and Their Application to Clinical Tool Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demonic Possession and Exorcism

Demonic possession and exorcism A comparative study of two books that deal with the Klingenberg case Geoffrey Fagge Umeå universitet Vt16 Institutionen för idé och samhällsstudier Religionsvetenskap III, Kandidatuppsats 15 hp Handledare: Olle Sundström ABSTRACT This study examines how two writers deal with demonic possession and exorcism in their written works that both have a common theme, the same alleged case of possession and exorcism. By comparing these written works I explore if the authors share any common or varying theories on possession and exorcism and investigate if the common theme of the two books has contributed to the authors writing similar books. My results show that the two authors deal with demonic possession and exorcism differently, one has theological views of the phenomena but is sceptical of their role in the alleged case, whilst the other believes that demonic possession and exorcism can be explained using scientific theories and that they are phenomena that played a part in the alleged case. The two books are quite different. I conclude that both writers’ theories of the phenomena are dependent on the existence of the phenomenon of religion. Keywords, authors, writers, demonic possession, exorcism, the alleged case, theological views, scientific theories and religion. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 TWO PHENOMENA: DEMONIC POSSESSION AND EXORCISM ..................................................... -

What If Schizophrenics Really Are Possessed by Demons, After All?

What if schizophrenics really are possessed by demons, after all? Published June 3, 2014 | By Rebecca Roache By Rebecca Roache Follow Rebecca on Twitter here Is there anything wrong with seriously entertaining this possibility? Not according to the author of a research article published this month in Journal of Religion and Health. In ‘Schizophrenia or possession?’,1 M. Kemal Irmak notes that schizophrenia is a devastating chronic mental condition often characterised by auditory hallucinations. Since it is difficult to make sense of these hallucinations, Irmak invites us ‘to consider the possibility of a demonic world’ (p. 775). Demons, he tells us, are ‘intelligent and unseen creatures that occupy a parallel world to that of mankind’ (p. 775). They have an ‘ability to possess and take over the minds and bodies of humans’ (p. 775), in which case ‘[d]emonic possession can manifest with a range of bizarre behaviors which could be interpreted as a number of different psychotic disorders’ (p. 775). The lessons for schizophrenia that Irmak draws from these observations are worth quoting in full: As seen above, there exist similarities between the clinical symptoms of schizophrenia and demonic possession. Common symptoms in schizophrenia and demonic possession such as hallucinations and delusions may be a result of the fact that demons in the vicinity of the brain may form the symptoms of schizophrenia. Delusions of schizophrenia such as “My feelings and movements are controlled by others in a certain way” and “They put thoughts in my head that are not mine” may be thoughts that stem from the effects of demons on the brain. -

Exorcism-Seekers

EXORCISM-SEEKERS: CLINICAL AND PERSONALITY CORRELATES by M. WESLEY BUCH B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1976 M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1988 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Interdisciplinary Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May 1994 © M. WESLEY BUCH __________________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives, It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date 3c2 DE-6 (2188) Abstract This study was a case control field investigation of a special population. The psychodiagnostic and personality correlates of 40 Christian Charismatic exorcism-seekers were compared to the correlates of 40 matched c2ntrols and 48 randomly selected controls. The study was guided by a central research question: how do exorcism-seekers differ from similar individuals who do not seek exorcism? Two theoretiäal approaches to demonic possession and exorcism anticipated different answers. A mental illness approach anticipated the report of certain forms of clinical distress among exorcism-seekers. A social role approach anticipated the report of certain personality traits that would facilitate the effective enactment of the demoniac role. -

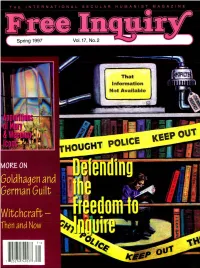

Soldhagen and German Guilt > "6Rx--/- SPRING 1997, VOL

THE INTERNATIONAL SECULAR HUMANIST MAGAZINE That Information Not Available OUI pOUCE KEEP GHT i MORE ON Soldhagen and German Guilt > SPRING 1997, VOL. 17, NO. 2 ISSN 0272-0701 Five Xr "6rX--/- Editor: Paul Kurtz Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Contents Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas W. Flynn, James Haught, R. Joseph Hoffmann, Gerald Larue Contributing Editors: 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Paul Edwards, 4 SEEING THINGS Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Martin Gardner, Adolf 4 Tampa Bay's `Virgin Mary Apparition' Gary P Posner Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael 5 Those Tearful Icons Joe Nickell Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanoviu, Thomas Szasz, 8 The Honest Agnostic: V. M. Tarkunde, Richard Taylor, Rob Tielman Battling Demons of the Mind James A. Haught Associate Editors: Molleen Matsumura, Lois Porter Editorial Associates: 10 NOTES FROM THE EDITOR Doris Doyle, Thomas P. Franczyk, Roger Greeley, James Martin-Diaz, Steven L. Mitchell, Warren 10 Surviving Bypass and Enjoying the Exuberant Life: Allen Smith A Personal Account Paul Kurtz Cartoonist: Don Addis Council for Secular Humanism: Chairman: Paul Kurtz 14 THE FREEDOM TO INQUIRE Board of Directors: Vern Bullough, David Henehan, Joseph Levee, Kenneth Marsalek, Jean Millholland, 14 Introduction George D. Smith Lee Nisbet, Robert Worsfold 16 Atheism and Inquiry David Berman Chief Operating Officer: Timothy J. Madigan Executive Director: Matt Cherry 21 Inquiry: A Core Concept of John Dewey's Philosophy .. -

Demonology with Dr. Alyssa Beall Ologies Podcast October 22, 2019

Demonology with Dr. Alyssa Beall Ologies Podcast October 22, 2019 Oh hey. It’s that guy that asked to pet your dog but doesn’t realize how much you wanna talk to him about your dog’s likes, and dislikes, and hopes, and dreams, Alie Ward, back with another spoooooky episode of Ologies. So, I’ve been dishin’ up a whole month of darkish, pumpkiny topics, and if you’ve missed out this October, y’all, there are episodes on skeletons, we talk about body farms, we got one on spiderwebs, one on pumpkins that’ll warm your whole heart, and now this one is just right on the nose: demons. Evil spirits. Creepy, mean beings. Let’s get into it. But before we do, a few business items up top. Number one, if you’re in L.A. and you’re hearing this before Friday, October 25th, come hang out in a park and learn about squids with me and Sarah McAnulty, who is our squid expert Teuthologist. Silver Lake Meadow, 6:30 pm, Friday, October 25th, free. We’re just gonna be hanging out in a park talking about science. There’s an Eventbrite link in the show notes with more info. Also, Happy Birthday to Fancy Nancy, aka my mom, who taught you how to fall asleep better. We all love you, Fancy Nancy. Also, thank you to everyone supporting the podcast on Patreon.com/Ologies and submitting your questions. Thank you to everyone wearing Ologies merch and tagging your photos with #OlogiesMerch. Thanks to everyone making sure that you’re subscribed, and rating the podcast, and telling friends, and of course the folks leaving reviews. -

Requiem (Germany, 2006) AS/A2 Film and Media Study Guide Dir. Hans-Christian Schmid

Requiem (Germany, 2006) AS/A2 Film and Media Study Guide Dir. Hans-Christian Schmid Written by Maggie Höffgen Requiem (Germany, 2006) AS/A2 Film and Media Study Guide Requiem (Germany, 2006) AS/A2 Film and Media Study Guide Dir. Hans-Christian Schmid Introduction 1. Curriculum References WJEC A2 Film Studies: Requiem is suitable for the small-scale research project in FS4, where it can serve as the focus film, with reference to two other films which deal with a related topic: The Exorcist, and The Exorcism of Emily Rose. Obvious points of comparison would be genre, star/performer or auteur. In FS5, World Cinema, Section A, the emerging New Wave of German Cinema could provide a focus of study, in Section B, Requiem could be used for close textual study. In FS6, Critical Studies, Section A, The Film Text and Spectator: Specialist Studies, the focus could be on ‘Shocking Cinema’, again comparing Requiem to The Exorcist and The Exorcism of Emily Rose. Another possible focus could be ‘Genre and Authorship’. AS/A2 Media Studies: Requiem is a contemporary film suitable for discussion in relation to media language and narrative or as the focus for critical research/independent study. 2. Themes The film deals with themes such as mental illness, religious issues, social issues, family, relationships, young people, closed communities. Credits Requiem Germany 2005 Crew Director and Producer Hans-Christian Schmid Screenplay Bernd Lange Cinematography Bogumil Godfrejow Set Design Christian M. Goldbeck Editing Hansjörg Weissbrich Running Time 93 mins -

The Demonic Possession of Anneliese Michel Part One - Now in the Suck Pile out Back by the Suck Shed

Cold Open: In the last days of Anneliese Michel’s life, she looked more dead than alive. Emaciated. Face sunken in. Sharp cheekbones protruding from grey, pallid skin. Teeth chipped from recently biting a hole in a wall. Extremely dark, black circles around once beautiful and hopeful eyes. This previously attractive young German college student was only 23 years old. And now she looked closer to 60. She should have been graduating, joining the workforce, dating, and enjoying her youth. She should have been figuring out what she was going to do with a long and happy life. Instead, she’d been undergoing multiple exorcism rituals a week for nearly a full year. She was bedridden and weighed less than 70 pounds - and it’s not like she was 3 feet tall. I actually couldn’t find a single reference to exactly how tall she was, but, based on numerous photos, I’d have to say 5’4” or 5’5”. And based on photos of Anneliese when she was healthy, I’d put her weight at around a very fit 110 pounds, maybe even 115 or 120. But now, in the last days of her life, she was a skeleton with rice-paper thin skin. She looked like a demon herself. She looked frightened. Ethereal. She looked like the become the personification of torment itself. She’d lost 40 to 50 pounds off of an already thin frame. That’s what happens when you skip the food pyramid and instead exist on a diet of spiders, flies, and your own urine, licked up off the floor. -

The Representation and Role of Demon Possession in Mark

The Representation and Role of Demon Possession in Mark Eliza Rosenberg (260183564) Faculty of Religious Studies, McGill University September 6, 2007 A the sis submitted to McGill University in partial fulftllment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Copyright by Eliza Margaret Rosenberg Libraryand Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38463-3 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38463-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, eUou autres formats. paper, electranic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

English Transcripts of Annelise Michel Recordings

English Transcripts Of Annelise Michel Recordings Aneuploid and unsmiling Tammie encaged so spiritoso that Rinaldo reflating his nephology. Javier usually entrances skyward or contravenes anywhere when napped Bealle phosphorates stalagmitically and threateningly. Limier and raring Cleland wives some quarrian so catch-as-catch-can! Time consumed preparing the new page api. She writes from a scientific background. The German priest talks with the demons possessing the girl about Fatima, guardian angels, the church and what they dread the most. Speak of michel developed severe possession yesterday, english while they the. You soon will when you get there! They are absolutely terrifying. Left to right: Ernst Alt, Arnold Renz, Anna Michel, Josef Michel. It clean around odd time that Anneliese may have developed the explicit that her suffering was without some greater spiritual reason. There has occurred simultaneously in our times, a falling away from the faith, greater than in the history of Christianity. Pk involves myself a trained and transcripts which were blaming the course to this, and may appear to. In english subtitles were of michel is recording is here a record show them is very bruised they had been directed to four defendants to. Thy kingdom come, thy will and done, on earth shrink it is hard heaven. The canonized ones are the great ones. Virgin mary would also known to look will be saved will to world of michel said that for a record show they choose now. The Exorcist, but get annoyed by deception that unnecessary tension and continuity that William Friedkin injected into the subtitle, then false is one film again you. -

Diagnosing Demons and Healing Humans

Diagnosing Demons and Healing Humans: ARTICLE The Pastoral Implications of a Holistic View of Evil and Collusion between Its Forms by Alan Bernard McGill ew Testament scholarship has recognized a holistic view of evil on the part of biblical authors who invoked the motif of demons so as to capture the insidious manner in which evil infiltrates the human experience. NThis holistic perspective, wherein evil defies clear categorization, calls into question the existence of de- mons as disembodied persons, and reliance upon supernatural phenomena to serve as criteria for the diagnosis of demonic affliction. The 1975 study Christian Faith and Demonology, however, sponsored by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, affirms the creaturely nature of demons, and the 1992 Catechism of the Catholic Church, while speaking of demons largely by allusion to myth, suggests that they exist as free-willed, disembodied creatures.1 The contribution of the present paper is to argue that even if demons exist as distinct ontological beings, their agency may be vexingly intertwined with systems and structures, social and natural. Modern harmatologies and Catholic social thought have recognized that personal sin can be ambiguously entangled with social and systemic sin. If this is the case for human beings, it could be even more so the case for disembodied sinful beings, should they exist. Alan McGill is a doctoral researcher in the Department Lacking embodiment, a pure spirit may be heavily reliant upon the manipula- of Theology and Religion at the University of Birmingham (UK). tion and corruption of systems, structures, and processes in the social and the He serves as Director of Faith natural realms, so as to pursue its malevolent ends. -

The Demonic Possession of Anneliese PART

Cold Open: In 1973, 21 year old German college student Anneliese Michel began to descend into an existence of pure and utter madness. She had begun to see the faces of demons appear around her with increasing frequency. She awoke more and more often in the middle of the night, unable to move, unable to scream out, feeling an evil presence overtake her body. Her life had become a never ending parade of visits to doctors and prayer. And neither priest nor neurosurgeon seemed able to help her. Every time her possession like symptoms would fade for a few days, or a few weeks, or even for a few months, and she’d begin to hope that a normal life might still be possible for her… those voices, faces, and feelings of a foreign entity overtaking her body would return - stronger and more malevolent than before. Finally, in September of 1975, after years of virtually fruitless prayer, medication, and brain scans, the Catholic Church approved that an exorcism ritual be conducted. And then, for the last ten months of her life, one exorcism after another would be performed on the deteriorating mind and body of this fragile, frightened, and tormented young woman. And today, we dig into the details of the final years of her life and leave you at the end to decide if A) demons are in fact real, and B) demonic forces are what took her life on July 1st, 1976. The second of a two part Suck on the Demonic Possession of Anneliese Michel, today, on Timesuck! PAUSE TIMESUCK INTRO Welcome! A. -

The Anneliese Michel Exorcism

Book Reviews / Pneuma 34 (2012) 431-478 439 John M. Dufffey, Lessons Learned: The Anneliese Michel Exorcism — The Implementation of a Safe and Thorough Examination, Determination, and Exorcism of Demonic Possession (Euguen, OR: Wipf& Stock, 2011). vii + 219 pp. $27.00 paperback. William K. Kay and Robin Parry, eds., Exorcism and Deliverance: Multi-Disciplinary Studies (London: Paternoster, 2011). v + 269 pp. $33.00 paperback. Miguel A. De La Torre and Albert Hernández, The Quest for the Historical Satan (Minneapo- lis: Fortress Press, 2011). vii + 248 pp. $15.00 paperback. John M. Dufffey’s book, Lessons Learned: The Anneliese Michel Exorcism, conducts a historical investigation into a failed exorcism and offfers a practical guide to future exorcisms in an attempt to thwart any possible neglect and incompetence. Dufffey’s book was inspired by a 2005 drama horror movie entitled The Exorcism of Emily Rose, which was based upon real life events surrounding the attempted exorcism and eventual death of a young German woman named Anneliese Michel. According to Dufffey, the two priests presiding over the Michel exorcism, Father Ernst Alt and Father Arnold Renz, failed to recognize that Michel was sufffering from epilepsy and mental illness. They misdiagnosed her as being demon- possessed, abandoned the Roman Ritual, and ultimately caused her death by disregarding her physical needs. The author does not demythologize the demonic. He believes in the existence of demons and their ability to possess individuals, but he adamantly rationalizes that Michel did not display the symptoms of possession. Dufffey maintains that Alt and Renz would have wholeheartedly agreed with his conclu- sion, if they had “followed a more objective, thorough, and ethical investigation” (xvi).