Published in Enduring Legacies, University of Colorado Press, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Bilingüismo En El Estado De Nuevo México: Pasado Y Presente

Tesis Doctoral 2013 El Bilingüismo en el estado de Nuevo México: pasado y presente Fernando Martín Pescador Licenciado en Filología Inglesa Universidad de Zaragoza DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍAS EXTRANJERAS Y SUS LINGÜÍSTICAS FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA Directora: María Luz Arroyo Vázquez DEPARTAMENTO DE FILOLOGÍAS EXTRANJERAS Y SUS LINGÜÍSTICAS FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN A DISTANCIA El Bilingüismo en el estado de Nuevo México: pasado y presente Fernando Martín Pescador Licenciado en Filología Inglesa Universidad de Zaragoza Directora: María Luz Arroyo Vázquez Agradecimientos A mi directora de tesis, María Luz Arroyo Vázquez, por todo el trabajo que ha puesto en esta tesis, por su asesoramiento certero, su disponibilidad e interés mostrados en todo momento. A Nasario García, Mary Jean Habermann, Tony Mares, Adrián Sandoval, Marisa Pérez, Félix Romeo y Ricardo Griego, que tuvieron la amabilidad de leer algunos de los capítulos y hacer comentarios sobre los mismos. Con todos ellos tuve conversaciones sobre mis progresos y todos ellos aportaron grandes dosis de sabiduría. A Mary Jean Habermann, Tony Mares y Lorenzo Sánchez, que, tuvieron, además, la gentileza de realizar una entrevista de vídeo para este trabajo. A Garland Bills, Felipe Ruibal, Joseph Sweeney y Neddy Vigil por reunirse a charlar conmigo sobre sus trabajos dentro del bilingüismo. A David Briseño, Rodolfo Chávez y Paul Martínez por incluirme en su equipo de la New Mexico Association for Bilingual Education, NMABE (Asociación para la educación bilingüe de Nuevo México) y permitirme colaborar en todas sus actividades. Gracias, también, a NMABE por otorgarme en 2012 el Matías L. -

EL RÍO D O-Your-Own-Exhibition Kit

EL RÍO D o-Your-Own-Exhibition Kit © 2003 Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC Teacher’s Guide Writers: Olivia Cadaval, Cynthia Vidaurri, and Nilda Villalta Editor: Carla Borden Copy Editor: Arlene Reiniger Education Specialist: Betty Belanus Education Consultants: Jill Bryson,Tehani Collazo, and Sarah Field Intern: Catherine Fitzgerald The “El Río Do-Your-Own-Exhibition” Kit has been produced by the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and supported by funds from the Smithsonian Latino Initiatives Fund, the Smithsonian Special Exhibition Fund, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Houston Endowment, Inc. Table of Contents Teacher’s Preface to the Teachers Guide Unit 1 Introduction Unit 2 El Río Story Unit 3 Where We Live: People and Geography Unit 4 How and What We Know:Traditional Knowledge Unit 5 Who We Are: Cultural Identity Unit 6 How We Work: Sustainable Development Unit 7 Bringing It All Together Additional El Río Six-part Videotape Materials —Part 1 Ranching:Work —Part 2 Ranching: Crafts and Foodways —Part 3 Shrimping —Part 4 Piñata-making —Part 5 Conjunto Music —Part 6 Fiesta of San Lorenzo in Bernalillo, New Mexico EL RÍO DO-YOUR-OWN-EXHIBITION KIT Exhibition Exhibition Sample 1 El Río Exhibition Floor Plan for Smithsonian Institution Samples List Exhibition Sample 2 El Río Exhibition Introduction Panel Exhibition Sample 3 El Río Exhibition Sample Panel Exhibition Sample 4 Exhibit Objects Exhibition Sample 5 People and Place Introduction Exhibition Sample 6 People and -

July 9 - 15, 2021

CALENDAR LISTING GUIDELINES • Submit Pasa Week calendar events via email to [email protected] at least two weeks prior to the event date. • Provide the following: event title, date, time, venue, brief description, ticket prices, contact phone number, and web address. • Inclusion of free listings is dependent on space availability. ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR CALENDAR COMPILED BY PAMELA BEACH July 9 - 15, 2021 FRIDAY 7/9 SATURDAY 7/10 Gallery Openings Gallery Openings Ellsworth Gallery Encaustic Art Institute 215 E. Palace Ave., 505-989-7900 505-424-6487, eainm.com/2021-global-warming- D1 & D2: Re-Connection, ceramics by Doug Black is-real-exhibit and paintings/sculpture by Doug Coffin; Global Warming is REAL, virtual group show reception 5-7 p.m. of encaustic-wax works; through Aug. 27. Horndeski Contemporary Santa Fe Opera season opener 703 Canyon Rd., 505-231-3731 or 505-438-0484 The Marriage of Figaro Music Paintings, narrative paintings by Gregory 301 Opera Dr., 800-280-4654, 505-986-5900 Horndeski; through Aug. 28; reception 5-8 p.m. Mozart’s comic opera of intrigue, misunderstand- Manitou Galleries ings, and forgiveness; 8:30 p.m.; $36-$278, simulcast 225-B Canyon Rd., 505-986-0440 $50-$125; santafeopera.org/operas-and-ticketing. Creatures and Critters, works by painter Amy Lay And, Wednesday, July 14. (See stories, Pages 24-32) and sculptor Paul Rhymer; through Aug. 7. Classical Music McLarry Fine Art 225 Canyon Rd., 505-988-1161 Chatter (In) SITE SITE Santa Fe, 1606 Paseo de Peralta, 505-989-1199 The Good Earth, landscapes by Peter Hagen; through July 23; reception 5-7 p.m. -

New Mexico Musician Vol 40 No 1

New Mexico Musician Volume 40 | Number 1 Article 1 9-1-1992 New Mexico Musician Vol 40 No 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_musician Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation . "New Mexico Musician Vol 40 No 1." New Mexico Musician 40, 1 (1992). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_musician/vol40/ iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Musician by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. @-lff FALL 199� inJ.jrr Inside: All-State Audition Information The Revised NMMEA Handbook NMMEA's Award Winners OFFICIAL PUBLICATION NEW MEXICO MUSIC EDUCATORS ASSOCIATION Volume XL WHEN??? FALL Band, Orchestra, Choir and Guitar Camps WINTER Christmas Concert Preparation SPRING Festival and Concert Preparation SUMMER Ten Weeks Music Camp Students Age 8 through 14 WHY??? Our clinicians and instrumental specialists teach sec tionals to prepare for your concert or festival. We accomplish in depth teaching in a woodland setting that combines music & outdoor recreation which in spires esprit-de-corps. WHO??? Cleveland Mid-School Band Jal High School Band Taos High School Band Grants NM Mid-School Band Los Alamos Mid-School Band Espanola High School Band Espanola Mid-School Band Lincoln Mid-School Band Las Cruces Mid-Schools Band Truman Mid-School Band Ruidoso Mid-School Band Mora High School Band Hayes Mid-School Band Clayton Schools Band Los Lunas Mid-School Band HUMMINGBIRD Jemez High School Band Highland High School Choir Socorro Mid-School Choir SUMMER MUSIC Jemez High School Choir and RECREATION CAMP Albq. -

Inside This Issue Icon of New Mexico, the American West, Articulated These Connections So Beautifully

Newsletter of the New Mexico Humanities Council Spring/Summer 2009 “If the landscape gave birth to American And while Ghost Ranch is one vehicle to help better understand New Mexicans’ identity, the West reaffirmed that existence.” attachment to place (and therefore get us closer to answering the RFP’s questions about “identity”) When we read that sentence in NMHC’s Mexico Press in July 2009. NMHC has we also know that if our project succeeds it request for proposals addressing the topic, contributed meaningfully to an important will be because so many visitors will leave the “What Does It Mean to Be a New Mexican?”, project, and we, in turn, will help further the exhibition thinking about their own deeply we immediately saw that our project was a council’s intent to explore “What it means to personal attachments to place. In short, our perfect fit. be a New Mexican.” exhibition’s educational promise is in uncovering In helping develop and deliver the multitude of personal narratives about special “Ghost Ranch and the Faraway places that provoke, inspire, and enlighten. Nearby,” we are working with a Ghost Ranch and the Faraway Nearby, the variety of humanities scholars, exhibition, will be presented at the Albuquerque artists, curators, and cultural Museum of Art and History from July 12 practitioners (for instance, through September 28, 2009, with the first Albuquerque Museum’s director, public slide-illustrated lecture on Sunday July 12 Cathy Wright and educational at 1 pm. The second presentation will be Friday curator, Elizabeth Becker have been July 17 at 6 pm at the new auditorium at the New key to developing the educational Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe, with three components of the exhibition). -

Galloway's Alabado and the Musical Traditions of the Penitentes

JAMES (SANTA FE) GALLOWAY’S ALABADO AND THE MUSICAL TRADITIONS OF THE PENITENTES Rebecca Weidman-Winter, B. M., M. M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2011 APPROVED: Terri Sundberg, Major Professor Bernardo Illari, Committee Member Kathleen Reynolds, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Weidman-Winter, Rebecca. James (Santa Fe) Galloway’s Alabado and the Musical Traditions of the Penitentes. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2011, 55 pp., 1 table, 37 musical examples, references, 39 titles. This dissertation explores the musical traditions of the Penitentes of New Mexico and how these traditions influenced James (Santa Fe) Galloway’s Alabado for soprano, alto flute, and piano. Due to geographical isolation and religious seclusion the music of the Penitential Brotherhood is not well known outside of these New Mexican communities. The focus of this study, as pertaining to the music of the Penitentes, is the alabado “Por el rastro de la cruz,” and the pito, a handmade wooden flute. Included in this paper are transcriptions of pito melodies performed by Vicente Padilla, Cleofes Vigil, Emilio Ortiz, and Reginald Fisher, which have been transcribed by John Donald Robb, William R. Fisher, Reginald Fisher, and Rebecca Weidman- Winter. Few resources are available on Galloway or Alabado, an unpublished work, yet the popularity of this piece is apparent from the regular performances at the National Flute Association Conventions and by flutists throughout the United States. -

El Camino Real De Tierra Adentro Archival Study

El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Prepared for: The New Mexico Spaceport Authority (NMSA) Las Cruces and Truth or Consequences, New Mexico The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Office of Commercial Space Transportation Compiled by: Jemez Mountains Research Center, LLC Santa Fe, New Mexico Contributors: Kristen Reynolds, Elizabeth A. Oster, Michael L. Elliott, David Reynolds, Maby Medrano Enríquez, and José Luis Punzo Díaz December, 2020 El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro As Revealed Through the Written Record: A Guide to Sources of Information for One of the Great Trails of North America Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Statement of Purpose .................................................................................................. 1 • Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 • Scope and Organization ....................................................................................................................... 2 • El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro: Terminology and Nomenclature ............................... 4 2. History of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro; National Historic Trail Status........................... 6 3. A Guide to Sources of Information for El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro .............................. 16 • 3.1. Archives and Repositories ....................................................................................................... -

Unlearning Rethinking Poetics, Pandemics, and the Politics of Knowledge

Unlearning Rethinking Poetics, Pandemics, and the Politics of Knowledge Charles L. Briggs Utah State University Press Logan Copyrighted material Not for distribution © 2021 by University Press of Colorado Published by Utah State University Press An imprint of University Press of Colorado 245 Century Circle, Suite 202 Louisville, Colorado 80027 All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America. The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of University Presses.. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State Uni- versity of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Wyoming, Utah State University, and Western Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1- 64642- 101- 5 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1- 64642- 102- 2 (ebook) https:// doi .org/ 10 .7330/ 9781646421022 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Briggs, Charles L., 1953– author. Title: Unlearning : rethinking poetics, pandemics, and the politics of knowledge / Charles L. Briggs. Description: Logan : Utah State University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021001139 (print) | LCCN 2021001140 (ebook) | ISBN 9781646421015 (paperback) | ISBN 9781646421022 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Folklorists. | Folklore—Study and teaching. | Mass media and folklore. | Applied folklore—Study and teaching. | Communication in folklore. Classification: LCC GR49 .B75 2021 (print) | LCC GR49 (ebook) | DDC 398.092—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001139 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001140 The University Press of Colorado gratefully acknowledges the support of the University of California, Berkeley, toward the publication of this book. -

La Musica De Los Viejitos: the Hispano Folk Music of the Rio Grande Del Norte

La MUsica de los Viejitos: The Hispano Folk Music of the Rio Grande del Norte Jack Loeffler Spanish culture came to northern New Mexi delight of local mice. A form related to the co with a musical heritage whose wellsprings lie romance is the relaci6n, a humorous narrative in European antiquity. Its traditions continued ballad still popular. One of the best relaciones is to evolve as descendants of the Spanish colonists entitled El Carrito Paseado, which was written in melded into the mestizaje of La Raza. the 1920s and tells the tale of an old, broken The mountains around the Rio Grande del down jalopy, Norte still ring with echoes of songs sung in Tengo un carrito paseado Spain hundreds of years ago in narrative ballads Que el que no lo ha experimentado called romances. This musical form branched off Nolo puedo hacer andar as early as the 12th century from the tradition of epic poetry and bloomed in the 13th century Tiene roto el radiador when juglares- wandering acrobats, jugglers, Descompuesto el generador poets, dancers and musicians - performed in Se le quebr6 la transmisi6n. public squares and noblemen's houses. Passed A form of narrative ballad that has evolved down through generations, these ballads gener from the romance is the corrido. Vicente Men ally exalted the deeds of warriors, kings and the doza, the late, eminent Mexican ethnomusicolo gentry. They were eagerly listened to by everyone gist stated, "The Mexican corrido, a completely including chroniclers and historians, who popular form .. .is an expression of the sensibility regarded the romances as popular accounts of of our people, and its direct ancestor, both liter significant events. -

Teaching Mathematics, Science and Social Studies. Student Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 284 442 FL 016 834 AUTHOR Santos, Sheryl L. TITLE Teaching Mathematics, Science and Social Studies. Student Edition. Bilingual Education Teacher Training Packets. Packet 3, Series C. INSTITUTION Dallas Independent School District, Tex. Dept. of Research and Evaluation. PUB DATE 82 NOTE 242p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Bilingual Education; Cross Cultural Training; Cultural Awareness; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; *English (Second Language); Faculty Development; Hispanic American Culture; Instructional Development; Instructional Materials; Second Language Instruction; *Social Studies; *Spanish; *Teacher Education; Teaching Guides ABSTRACT The teacher training materials contained in this manual form part of a series of packets intended for use in bilingual (Spanish-English) instruction by institutions of higher education, education service centers, and local school district inservice programs and address the content, methods, and materials for teaching effectively in the subject matter areas of mathematics, science, and social studies. Technical vocabulary is included and less commonly-taught information topics in science and social studies are presented. The manual's first section covers content development for bilingual social studies and features readings about the Spanish-speaking cultures, the Spanish language, and cultural and education needs of Americans of Spanish-speaking origin. Exercises for assessing intercultural knowledge, vocabulary, and bilingual and multicultural aspects are included. The aecond section features readings and exercises addressing teaching methods and strategies for the bilingual classroom. The third and last features readings, resources, and exercises regarding the development of English as a second language skills through social studies instruction. -

Ceremonial Music and Cultural Resistance on the Upper Rio Grande

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 65 Number 1 Article 2 1-1-1990 Las Entriegas: Ceremonial Music and Cultural Resistance on the Upper Rio Grande Enrique R. Lamadrid Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Lamadrid, Enrique R.. "Las Entriegas: Ceremonial Music and Cultural Resistance on the Upper Rio Grande." New Mexico Historical Review 65, 1 (1990). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol65/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Las Entriegas: Ceremonial Music and Cultural Resistance on the Upper Rio Grande. Research Notes and Catalog of the Cipriano Vigil Collection, 1985-1987 ENRIQUE R. LAMADRID The "Entriega de novios" (Delivery of the newlyweds) is a folk wedding· ceremony sung in verse, a subtle and complex counter ritual with roots in the religious customs and cultural conflicts of nineteenth-century New Mexico. As Juan B. Rael and other scholars have noted, wedding music and songs are used throughout Latin America and Spain, but none are as developed or share the same scope and ritual function as the "Entriega de novios" of the Upper Rio Grande, the Hispanic cultural area in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. 1 The "Entriega de novios" is the last formal event in a traditional marriage celebration. In the secular space of a dance hall or private home, an entregador(a) (deliverer) sings both fixed and improvised verses which congratulate, admonish, and bless the newlyweds and their families in their new set of relations. -

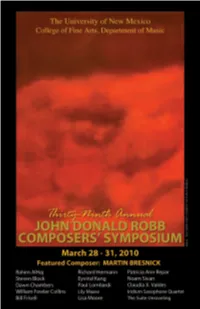

Composers Symp Pgm10.Pdf

Creative Soundspace Festival 2010 SPRING 2010 HIGHLIGHTS Kate McGarry Trio Zakir Hussain & Masters of Percussion Michael Anthony Trio w. Kanoa Kaluhiwa Southwest Jazz Orchestra Bill Frisell, Rahim AlHaj, Eyvind Kang ABQ Grand Slam Gretchen Parlato Quartet Roshan Jamal Bhartiya w. Ty Burhoe Omar Sosa’s Afreecanos Bassekou Kouyate & Ngoni Ba Gabriel Alegría’s Afro Peruvian Sextet Thursday, 7:30pm APRIL 1 Lisa Gill w. Michael Vlatkovich Trio César Bauvallet y Tradiciones Lily Maase & The Suite Unraveling Fred Sturm Ravish Momin’s Trio Tarana Doug Lawrence Group presented in partnership with the Rory Block John Donald Robb UNM Composers’ Symposium Ila Cantor w. Matt Brewer Loren Kahn Puppet & Object Theater Friday, 7:30pm APRIL 2 Cal Haines Trio J.A. Deane’s Harmonograph 2 X2 Joy Harjo w. Larry Mitchell Straight Up w. Arlen Asher & Bobby Shew Mark Weaver’s UFO Ensemble Lou Donaldson Quartet OUTPOST Performance Space 210 YALE SE • 268-0044 • www.outpostspace.org EXPERIENCE JAZZ IN NEW MEXICO LAND OF ENCHANTMENT Funded in part by the New Mexico Tourism Department FEATURED COMPOSER Martin Bresnick Rahim AlHaj Eyvind Kang Steven Block Paul Lombardi Dawn Chambers Lily Maase William FowlerJohn Collins Donald RobbPatricia Ann Repar Bill Frisell ’ Noam Sivan RichardComposers Hermann SymposiumClaudia X. Valdes ARTIST IN RESIDENCE Lisa Moore ENSEMBLES IN RESIDENCE Iridium Saxophone Quartet • The Suite Unraveling Symposium events are held at the University of New Mexico, Center for the Arts. All events are free and open to the public. Dr. James Linnell, Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts Dr. Steven Block, Chair, Department of Music COMPOSERS’ SYMPOSIUM STAFF Dr.