Serving Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mon 18 Apr 2005 / Lun 18 Avr 2005

No. 130A No 130A ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 38th Parliament Première session, 38e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Monday 18 April 2005 Lundi 18 avril 2005 Speaker Président Honourable Alvin Curling L’honorable Alvin Curling Clerk Greffier Claude L. DesRosiers Claude L. DesRosiers Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Copies of Hansard Exemplaires du Journal Information regarding purchase of copies of Hansard may Pour des exemplaires, veuillez prendre contact avec be obtained from Publications Ontario, Management Board Publications Ontario, Secrétariat du Conseil de gestion, Secretariat, 50 Grosvenor Street, Toronto, Ontario, M7A 50 rue Grosvenor, Toronto (Ontario) M7A 1N8. Par 1N8. Phone 416-326-5310, 326-5311 or toll-free téléphone : 416-326-5310, 326-5311, ou sans frais : 1-800-668-9938. -

The Informer

Winter 2019 Table of Contents Welcome, Former Parliamentarians! We hope you’ve been staying warm. Below is a list of what you’ll find in the latest issue of The InFormer. Our annual holiday social/ 2 In conversation with John O’Toole/ 9 In conversation with Cindy Forster/ 11 In conversation with Sandra Pupatello/ 13 In conversation with Nokomis O’Brien/ 15 In conversation with Catherine Hsu/ 16 The artists who created the art in Queen’s Park/ 19 Political mentors/ 20 Unveiling Speaker Levac’s portrait/ 23 Spotlight on history/ 25 Behind the scenes/ 26 In loving memory of John Roxborough Smith/ 29 At the back of this newsletter, please find attached the 2019 OAFP membership renewal form. 1 Social Our Annual Holiday Social This joyous occasion was held in our newly renovated board room. The fes- tive atmosphere was enhanced with delicious food, refreshing beverages and sparkling conversation. As always, Joe Spina brought some fabulous Italian pastries. It was a great turnout of current and former Members. The gathering of about 60 people included Professors Fanelli and Olinski, two very strong supporters of our Campus Program, former Premier Kathleen Wynne, several newly elected MPPs, Legislative staffs, numerous former Members and our two Interns, Victoria Shariati and Zena Salem. A Special guest was Speaker Arnott.We took the occasion to present Speaker Arnott with the scroll proclaiming him an Honorary Member of O. A. F. P. The warmth of the occasion was wonderful, as you can tell with the photos we have included. All photos by Zena Salem. 2 Social David Warner and Jean-Marc Lalonde OAFP Scroll for Speaker Arnott 3 Social The many food options. -

Item 13 Ontario Legislature Internship Programme Director Report 2013-2014 Henry J

Item 13 Ontario Legislature Internship Programme Director Report 2013-2014 Henry J. Jacek, Academic Director Introduction This is my tenth year as Academic Director of the Ontario Legislature Internship Programme (OLIP). I could not do this job unless I had a capable and wise Programme Assistant. I am very fortunate to have an outstanding person in this position in Eithne Whaley, a former intern in the British House of Commons, now in her eleventh year with the Programme. Also in our management are two excellent employees of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, coordinators Rick Sage and William Short. Rick is a Research Librarian in the Legislative Library and Research Service and he is in his first year as a Programme Coordinator. Will is the Legislative Committee Clerk for two Standing Committees, Public Accounts and Justice Policy. Finally I thank Dagmar Soennecken, an Assistant Professor at York University, for her help in the intern selection process. Dagmar was an intern in 1998-1999. Every Friday the management team have a two-hour meeting with the ten interns. I think I can speak for all of us and say that this is the most enjoyable time of the week as we discuss the legislative events of the week, the recent experiences of the interns and the plans for future OLIP activities. As well we discuss the research projects of the interns, the fruit of which are the papers the interns present at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association. Intern Educational Activities: Orientation The core of the intern programme is the placements with two members of the Legislative Assembly, one with the government side and one with the opposition side. -

Mon 28 Apr 2014 / Lun 28 Avr 2014

o No. 132 N 132 ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario Second Session, 40th Parliament Deuxième session, 40e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Monday 28 April 2014 Lundi 28 avril 2014 Speaker Président Honourable Dave Levac L’honorable Dave Levac Clerk Greffière Deborah Deller Deborah Deller Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 325-3708. Hansard Reporting and Interpretation Services Service du Journal des débats et d’interprétation Room 500, West Wing, Legislative Building Salle 500, aile ouest, Édifice du Parlement 111 Wellesley Street West, Queen’s Park 111, rue Wellesley ouest, Queen’s Park Toronto ON M7A 1A2 Toronto ON M7A 1A2 Telephone 416-325-7400; fax 416-325-7430 Téléphone, 416-325-7400; télécopieur, 416-325-7430 Published by the Legislative Assembly of Ontario Publié par l’Assemblée législative de l’Ontario 6811 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ASSEMBLÉE LÉGISLATIVE OF ONTARIO DE L’ONTARIO Monday 28 April 2014 Lundi 28 avril 2014 The House met at 1030. -

The Informer

MONTHLY UPDATE!APRIL 2012 ONTARIO PARLIAMENT The Ontario Association of Former Parliamentarians Editorial: David Warner (Chair), Lily Munro, Joe Spina and Alexa Hu&man Welcome New Members Caplan, David !2011 Gilles, Phillip !! !2011 Johnson, Rick ! 2011 Lalonde, Jean-Marc !2011 Rinaldi, Lou ! 2011 Ruprecht, Tony !2011 Sterling, Norm !2011 Van Bommel, Maria ! 2011 Wilkinson, John ! 2011 Allen, Richard!!!2012 Dambrowski, Leona! !2012 Brownell, Jim ! 2012 Eves, Ernie !2012 The flag at the front of the Legislature is flown at half mast on Phillips, Gerry !2012 March 15,2012 to honour deceased member Tony Silipo. Pupatello, Sandra !2012 This issue will cover the Ottawa regional meeting, the Runciman, Robert ! 2012 Smith Monument, honouring Tony Silipo, the Annual Watson, Jim ! 2012 General Meeting and our regular Where Are They Now? ! PAGE 1 MONTHLY UPDATE!APRIL 2012 Introducing the New Speaker of the House Dave Levac was born and raised in the southwestern First elected to the Ontario Legislature in Ontario community of 1999 as the MPP for the riding of Brant, Brantford, where he Dave has since been re-elected three continues to live with his times. At the Legislature, he has held wife, Rosemarie. They have positions as the Public Safety & Security three adult children. Critic, Chief Government Whip and Chair of the Cabinet's Education After teaching elementary Committee and the Chair of the and secondary school for 12 Economic, Environment, and Resources years, Dave became an Policy Committee. He also served as the elementary school principal Parliamentary Assistant for the Minister in 1989. In his capacity as a of Community Safety and Correctional principal, Dave developed Services and later, the Minister of Energy conflict resolution programs and Infrastructure. -

FAO Annual Report 2016 EN

Annual Report 2015-2016 fao-on.org 2 Bloor Street West, Suite 900 Toronto, Ontario M4W 3E2 416-644-0702 fao-on.org [email protected] © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016 ISSN 2369-4289 (Print) ISSN 2369-4297 (Online) This document is also available in an accessible format and as a downloadable PDF at fao-on.org July 2016 The Honourable Dave Levac Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario Room 180, Main Legislative Building Queen’s Park Toronto, Ontario M7A 1A2 Dear Mr. Speaker: In accordance with section 14 of the Financial Accountability Officer Act, 2013 (the FAO Act), I am pleased to present the 2015–2016 Annual Report of the Financial Accountability Officer for your submission to the Legislative Assembly at the earliest reasonable opportunity. Sincerely, Stephen LeClair Financial Accountability Officer TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 1 Independence 3 Mandate and activities 5 Access to information 9 Legislative Assembly and information 19 Reporting and disclosure of information 25 Accountability 27 Financial statement 29 Office organization 31 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY1 he Financial Accountability Officer (FAO) is an independent officer of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. THis role is to provide the Assembly with the economic and financial analysis it needs to perform its constitutional functions, especially scrutinizing the government’s fiscal plan and its implementation over the course of the fiscal year. Mandate and activities The FAO performs this role by providing the Assembly with analysis on his own initiative and responding to research requests from MPPs and the committees on which they serve. In 2015-16, the FAO published two reports resulting of these requests have been partially fulfilled and two from analytical projects he initiated: An Assessment have not been fulfilled. -

The Informer and the Institutions

THE ONTARIO ASSOCIATION OF FORMER PARLIAMENTARIANS WINTER 2018 Bill 65 passed on May 10, 2000 during the 37th Session, founded the Ontario Association of Former Parliamentarians. It was the first Bill in Ontario history to be introduced by a Legislative Committee. Table of Contents Meet the Interns—2 Holiday Social Recap—3-4 OAFP Campus program—5 Interview with Iain Angus—5-8 Interview with John Hastings—9-11 Interview with Michael Prue—12 - 14 Advice From Former Members on Entering Politics—15 - 17 Notice: Nominations for D.S.A.—18 Interview Dr. Marie Bountrogianni—19 - 21 Queen Park’s Staircase To Nowhere 22- 23 Obituary: Ron Van Horne—24 Membership Renewal—25 Contact Us—26 1 Meet The Interns Emerald Bensadoun is a freelance journal- Dylan Freeman-Grist is a journalist and ist and communications specialist who cre- communications professional currently com- ates digital content. pleting his journalism degree at Ryerson Fascinated by governance and poli- University. cy, Emerald is interested in learning more An aspiring arts writer Dylan hopes about journalism in politics, and looking for to one day work in arts media while finding opportunities to apply existing skills and new platforms to advocate for and examine knowledge to solve the challenging problems contemprary Canadian culture. facing Canadian politics, society, and Dylan joined the InFormer and the institutions. Emerald began working with the Ontario Association of Former Parlimenta- Otario Association of Former Parliamentari- rians as a way to sharpen skills and learn ans to learn about the parliamentarians be- first-hand from those who have served in hind the policy and has thoroughly enjoyed office how government and policy can impact her time working with OAFP. -

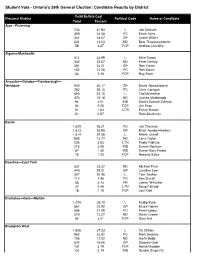

Candidate Results W Late Results

Student Vote - Ontario's 39th General Election: Candidate Results by District Valid Ballots Cast Electoral District Political Code Name of Candidate Total Percent Ajax—Pickering 743 41.93 L Joe Dickson 409 23.08 PC Kevin Ashe 331 18.67 GP Cecile Willert 231 13.03 ND Bala Thavarajasoorier 58 3.27 FCP Andrew Carvalho Algoma-Manitoulin 514 33.99 L Mike Brown 432 28.57 ND Peter Denley 351 23.21 GP Ron Yurick 152 10.05 PC Ron Swain 63 4.16 FCP Ray Scott Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough— Westdale 940 30.17 GP David Januczkowski 782 25.10 PC Chris Corrigan 690 22.15 L Ted Mcmeekin 473 15.18 ND Juanita Maldonado 94 3.01 IND Martin Samuel Zuliniak 64 2.05 FCP Jim Enos 51 1.63 COR Eileen Butson 21 0.67 Sam Zaslavsky Barrie 1,629 26.21 PC Joe Tascona 1,613 25.95 GP Erich Jacoby-Hawkins 1,514 24.36 L Aileen Carroll 856 13.77 ND Larry Taylor 226 3.63 LTN Paolo Fabrizio 215 3.45 IND Darren Roskam 87 1.39 IND Daniel Gary Predie 75 1.20 FCP Roberto Sales Beaches—East York 531 35.37 ND Michael Prue 440 29.31 GP Caroline Law 307 20.45 L Tom Teahen 112 7.46 PC Don Duvall 56 3.73 FR James Whitaker 37 2.46 LTN Doug Patfield 18 1.19 FCP Joel Kidd Bramalea—Gore—Malton 1,079 38.70 L Kuldip Kular 667 23.92 GP Bruce Haines 588 21.09 PC Pam Hundal 370 13.27 ND Glenn Crowe 84 3.01 FCP Gary Nail Brampton West 1,526 37.23 L Vic Dhillon 962 23.47 PC Mark Beckles 706 17.22 ND Garth Bobb 642 15.66 GP Sanjeev Goel 131 3.19 FCP Norah Madden 131 3.19 IND Gurdial Singh Fiji Brampton—Springdale 1,057 33.95 ND Mani Singh 983 31.57 L Linda Jeffrey 497 15.96 PC Carman Mcclelland -

ANNEXURE “1” the Official Declaration by the Republic of India

ANNEXURE “1” The official declaration by the Republic of India in the Gazette of India, announcing the banning of the Human Rights Advocacy Group Sikhs For Justice on July 22nd 2019, and extending the powers of the Central Government under the UAPA laws to the state governments of Punjab, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi and Chandigarh Administration in relation to the above said unlawful association. jftLVªh laö Mhö ,yö&33004@99 REGD. NO. D. L.-33004/99 vlk/kj.k EXTRAORDINARY Hkkx II—[k.M 3—mi -[k.M (ii) PART II—Section 3—Sub-section (ii) izkf/dkj ls izdkf'kr PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY la- 2387] ubZ fnYyh] lkseokj] tqykbZ 22] 2019@vk"kk<+ 31] 1941 No. 2387] NEW DELHI, MONDAY, JULY 22, 2019/ASHADHA 31, 1941 गृह मंJालयगृह मंJालय अिधसूचनाअिधसूचनाअिधसूचना नई Ƙदली, 22 जुलाई, 2019 का. आका. आ.आ. 2612612617261777(अ)(अ)(अ)(अ)....—जबƘक, के L सरकार ने िविधिवďŵ Ƙ;याकलाप (िनवारण) अिधिनयम, 1967 (1967 का 37) कƙ धारा 3 कƙ उप-धारा (1) और (3) ůारा Oद त शिŎयĪ का Oयोग करते ćए िसϞ स फॉर जिटस (एसएफजे) को Ƙदनांक 10 जुलाई, 2019 के भारत के राजपJ, असाधारण, भाग II, खड 3, उप-खड (ii) मĞ Oकािशत Ƙदनांक 10 जुलाई, 2019 कƙ अिधसूचना सं. का.आ. 2469(अ) के तहत एक िविधिवďŵ संगम घोिषत Ƙकया है; अ त:, अब, िविधिवďŵ Ƙ;याकलाप (िनवारण) अिधिनयम, 1967 (1967 का 37) कƙ धारा 42 ůारा Oदत ůारा यह िनदेश देती है Ƙक उϝत शिŎयĪ का Oयोग करते ćए, के L सरकार एतद् अिधिनयम कƙ धारा 7 और धारा 8 के अंतगϕत उसके ůारा Oयोग कƙ जा सकने वाली समत शिŎयĪ का पंजाब, हƗरयाणा, ज मू एवं क मीर, राज थान, उ तर Oदेश, उ तराख ड, Ƙदली के राƎीय राजधानी ϓेJ कƙ राϤय सरकारĪ तथा चडीगढ़ Oशासन ůारा भी उपयुϕϝ त िविधिवďŵ संगम के संबंध मĞ Oयोग Ƙकया जाएगा। [फा. -

Dieu Et Mon Droit: the Marginalization of Parliament and the Role of Neoliberalism in The

DIEU ET MON DROIT: THE MARGINALIZATION OF PARLIAMENT AND THE ROLE OF NEOLIBERALISM IN THE FUNCTION OF THE ONTARIO LEGISLATURE FROM 1971 TO 2014 By Thomas E. McDowell A dissertation presented to Ryerson University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the program of Policy Studies Ryerson University Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2016 ©Thomas E. McDowell 2016 AUTHOR'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Dieu et Mon Droit: The Marginalization of Parliament and the Role of Neoliberalism in the Function of the Ontario Legislature from 1971 to 2014 By Thomas E. McDowell Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Policy Studies, Ryerson University ABSTRACT In recent years, considerable attention has been paid to the increasingly popular trend among western governments to use arcane parliamentary mechanisms to circumvent the legislative process. However, despite growing concern for the influence of parliament, there are few comprehensive studies that capture the evolution of this pattern in the detail necessary to draw substantive conclusions about why it is occurring. -

Examining the Use of Ontario Parliamentary Convention to Guide the Conduct of Elected Officials in Ontario

Understanding the Unwritten Rules: Examining the use of Ontario Parliamentary Convention to Guide the Conduct of Elected Officials in Ontario by Ian Stedman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Faulty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Ian Stedman 2015 Understanding the Unwritten Rules: Examining the use of Ontario Parliamentary Convention to Guide the Conduct of Elected Officials in Ontario Ian Stedman Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Government ethics legislation in Canada guides and restricts the conduct of parliamentarians. Ontario established an independent officer of the legislature in 1988 who is responsible for administering its government ethics legislation. In 1994, an undefined behaviour-guiding standard called “Ontario parliamentary convention” was added to the legislation. This paper explores the history of Ontario’s government ethics regime and examines its response to specific scandals, in order to describe the emergence of Ontario parliamentary convention as a ii standard of conduct. It then provides a full discussion and complementary summary of the specific parliamentary conventions that Ontario’s legislative ethics officers have determined must guide the conduct of Ontario’s parliamentarians. This discussion and summary illuminate the problematic and inconsistent use of this standard by Ontario’s legislative ethics officers. Two sets of recommendations are then offered to help modernize and strengthen the legislation for the benefit of Ontario’s parliamentarians. iii Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to my wife and children for their support and patience throughout the completion of this thesis. Aimy, Lia and Ivy have spent a great deal of time this past year without their husband and father and this accomplishment is as much theirs as it is mine. -

Legislative Assembly Assemblée Législative of Ontario De L'ontario

o No. 133 N 133 ISSN 1180-2987 Legislative Assembly Assemblée législative of Ontario de l’Ontario First Session, 41st Parliament Première session, 41e législature Official Report Journal of Debates des débats (Hansard) (Hansard) Wednesday 9 December 2015 Mercredi 9 décembre 2015 Speaker Président Honourable Dave Levac L’honorable Dave Levac Clerk Greffière Deborah Deller Deborah Deller Hansard on the Internet Le Journal des débats sur Internet Hansard and other documents of the Legislative Assembly L’adresse pour faire paraître sur votre ordinateur personnel can be on your personal computer within hours after each le Journal et d’autres documents de l’Assemblée législative sitting. The address is: en quelques heures seulement après la séance est : http://www.ontla.on.ca/ Index inquiries Renseignements sur l’index Reference to a cumulative index of previous issues may be Adressez vos questions portant sur des numéros précédents obtained by calling the Hansard Reporting Service indexing du Journal des débats au personnel de l’index, qui vous staff at 416-325-7410 or 416-325-3708. fourniront des références aux pages dans l’index cumulatif, en composant le 416-325-7410 ou le 416-325-3708. Hansard Reporting and Interpretation Services Service du Journal des débats et d’interprétation Room 500, West Wing, Legislative Building Salle 500, aile ouest, Édifice du Parlement 111 Wellesley Street West, Queen’s Park 111, rue Wellesley ouest, Queen’s Park Toronto ON M7A 1A2 Toronto ON M7A 1A2 Telephone 416-325-7400; fax 416-325-7430 Téléphone, 416-325-7400; télécopieur, 416-325-7430 Published by the Legislative Assembly of Ontario Publié par l’Assemblée législative de l’Ontario 7157 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY ASSEMBLÉE LÉGISLATIVE OF ONTARIO DE L’ONTARIO Wednesday 9 December 2015 Mercredi 9 décembre 2015 The House met at 0900.