Towards a [Re]Conceptualisation of Power in High-Performance Athletics in the UK a CONSTERDINE Phd 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 INTRODUCTION from the CHAIR Carol Anthony Chair, Welsh Athletics

ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 INTRODUCTION FROM THE CHAIR Carol Anthony Chair, Welsh Athletics The specific achievements which • Continued to meet all the core targets set performances of the current champions. are detailed in other areas of the by our major funding partners This proved to be the perfect forum to • Maintained financial stability honour the past icons of our sport and to report, illustrate the outcomes inspire our current and future athletes. of the hard work of our dedicated • Introduced a new Club Modernisation “ I am delighted to Programme. From a strategic perspective, 2018 will staff and volunteer workforce • Supported the development of athletes be a very important year for us. We will and the talent and commitment of and coaches continue our focus on Governance as we our athletes during the year. • Restructured the Performance Team review our current structure in terms of to support Elite Performance. effectiveness and efficiency. We will also introduce the 2017 embark on a consultation programme with • Developed the Run Wales initiative all our stakeholders as we start to plan Our commitment to achieving the highest to support social running in Wales standards in all aspects of our sport, the details of our new Strategic Plan. It is • Provided competitive opportunities important that we adopt an inclusive ‘whole together with our willingness to embrace at all levels in all disciplines innovation, has been recognised by Sport team’ approach to the preparation of the plan, with input from all areas of the sport, Annual Report as it Wales and it is particularly pleasing to Our membership figures have continued to so that the final plan is one that everyone report that Welsh Athletics will play an increase and this is testament to the great can take ownership of in a positive and important role in the pilot phase of the work of our dedicated volunteers in the coherent way. -

Athletics Inclusive April - June 2021

ATHLETICS INCLUSIVE APRIL - JUNE 2021 Welcome to the second edition of the quarterly equality, diversity and inclusion news from UK Athletics, Athletics Northern Ireland, England Athletics, Scottish Athletics and Welsh Athletics. PARA INCLUSION Welsh Athletics As part of our ongoing commitment to closer working with Disability Sport Wales [DSW], Welsh Athletics is in the process of recruiting a jointly funded Para Athletics Pathway Coordinator. We have seen great recent success at the European Para-athletics Championships with a total of 7 medals from Welsh Athletes and we hope this joint working will continue and build on this success as the organisation become more closely integrated. The role will support the development and progression of Para Athletes within the Athletics Pathway (from community through to performance) as identified by Disability Sport Wales and Welsh Athletics. It will aim to ensure that all Para Athletes within the pathway have access to appropriate and meaningful community opportunities to support individual needs. There will also be mentoring and upskilling outreach support for athletes, coaches, clubs and key contacts in collaboration with the DSW Performance Pathway Team and WA. This is an exciting opportunity in a role which will be fully integrated into the Welsh Athletics Performance team at the start of preparations for the Birmingham 2022 Games. Scottish Athletics With athletics training returning across the country, a Safe Return to Training guide has been produced for wheelchair and frame running to remind athletes, coaches and clubs of the extra safety considerations. The guidance highlights equipment checks, how to minimise risks, training safely on the track and training safely on the road. -

Team Dimension Data an Post Chain Reaction Orica

Team Dimension Data An Post Chain Reaction Orica BikeExchange Roger Hammond Kurt Bogaerts Matthew Wilson 1 Mark Cavendish GBR 71 Nicolas Vereecken BEL 141 Caleb Ewan AUS 2 Steve Cummings GBR 72 Japer Bovenhuis NED 142 Alex Edmondson AUS 3 Bernhard Eisel AUT 73 Emiel Wastyn BEL 143 Michael Hepburn AUS 4 Mark Renshaw AUS 74 Oliver Kent-Spark AUS 144 Luka Mezgec SLO 5 Jay Robert Thomson RSA 75 Jacob Scott GBR 145 Robert Power AUS 6 Johann Van Zyl RSA 76 Damien Shaw IRL 146 Amets Txurruka ESP Team Sky Cannondale Drapac Pro Cycling Wanty Group Gobert Kurt Arvesen Eric Van Lancker Steven De Neef 11 Elia Viviani ITA 81 Jack Bauer NZL 151 Mark McNally GBR 12 Ian Stannard GBR 82 Dylan Van Baarle NED 152 Enrico Gasparotto ITA 13 Wout Poels NED 83 Sebastian Langeveld NED 153 Marco Marcato ITA 14 Nicolas Roche IRL 84 Ryan Mullen IRL 154 Guillaume Martin FRA 15 Ben Swift GBR 85 Wouter Wippert NED 155 Xandro Meurisse BEL 16 Danny Van Poppel NED 86 Ruben Zepuntke GER 156 Bjorn Thurau GER Team WIGGINS Caja Rural - Seguros RGA Madison Genesis Simon Cope Jose Miguel Fernandez Mike Northey 21 Sir Bradley Wiggins GBR 91 Carlos Barbero ESP 161 Erick Rowsell GBR 22 Jonathan Dibben GBR 92 Miguel Ángel Benito ESP 162 Alexandre Blain FRA 23 Owain Doull GBR 93 Javier Francisco Aramendia ESP 163 Taylor Gunman NZL 24 Mark Christian GBR 94 Andre Domingos Goncalez POR 164 Matt Holmes GBR 25 Chris Latham GBR 95 Diego Rubio ESP 165 Matt Cronshaw GBR 26 Daniel Pearson GBR 96 Héctor Saez ESP 166 Tom Stewart GBR Etixx Quick-Step Great Britain Team Giant Alpecin Brian Holm -

Sport Waleschwaraeon Cymru

SPORTSPORTT WWALEWALEALESS CHWARARAEONARAEAEONON CCYMRCYMRYMRUU ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019/20 SPORT WALE SPORT S SPORT WALES SPORT WALES ANNUAL REVIEW 2019/20 REVIEW ANNUAL LAWRENCE CONWAY, CHAIR CONWAY, LAWRENCE FROM A MESSAGE THE SPORTS COUNCIL FOR WALES AND SPORTS COUNCIL FOR WALES TRUST 1 APRIL 2019 - 31 MARCH 2020 ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS The Annual Report incorporates the Performance Report including the Sustainability Report, and the Accountability Report including Remuneration Report. The Sports Council for Wales has adopted International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). THIS YEAR SPORT WALES LAUNCHED OUR NEW Sport Wales is a Sole Trustee of the Sports Council for Wales Trust. STRATEGY. THE LAUNCH WAS, OF COURSE, JUST THE BEGINNING. THE HARD WORK IS NOW UNDERWAY TO HISTORY AND STATUTORY BACKGROUND ENSURE THAT WE ‘ENABLE SPORT IN WALES TO The Sports Council for Wales (known by its trade name Sport Wales) was established by Royal Charter dated 4 February 1972, with the objectives of “fostering the THRIVE’ AND THAT WE ARE ABLE TO SHARE AND knowledge and practice of sport and physical recreation among the public at large in EMBED THIS GOAL ACROSS THE SECTOR, REACHING Wales and †he provision of facili†ies †here†o". I† is financed by annual funding from †he ALL COMMUNITIES OF WALES. Welsh Government and from income generated from its activities. These Statements of Account are prepared pursuant to Article 15 of the Royal Charter for the Sports Sport partnerships and collaboration will form a key part of the Council for Wales (Sport Wales) in a form determined by the Welsh Government with strategy’s success. -

Board of Governors' Annual Report

BOARD OF GOVERNORS’ ANNUAL REPORT A long established tradition of achievement, success, quality teaching and learning 2010/2011 FOREWORD The Board of Governors’ Report for 2010/2011 is a clear, impressive and detailed record of the school’s continuing work and achievement. The community which St. Mary’s serves can be confident about its unrivalled dedication to the pursuit of excellence for each pupil in its care. From its first days, the school’s motto has been “Gloria Deo Soli.” It is inspirational and re-assuring that these words continue to inform and motivate the ethos, life and work of the school. As I commend this Report to you, I wish to pay tribute to my predecessor, Mr David Lambon. His vision for and dedication to the success and continued development of the school is very much in evidence in these pages. The St. Mary’s community has been enriched by his indefatigable determination to maintain the highest standards in every aspect of the school’s life and work. Should you wish to discuss any issue arising from the contents of this report, please do not hesitate to contact me at the school (8:30am-5:00pm) on or before 8 December 2011. __________________ D Gillespie (Mrs) Principal and Correspondent to the Board of Governors December 2011 CHAIRMAN’S INTRODUCTION I am very pleased indeed to introduce the Board of Governors’ Annual Report for 2010/2011. In June 2011, Mr David Lambon, Principal (2004-2011) left St. Mary’s to accept a new Principalship in St. Malachy’s College, Belfast. -

Cover Contents SD384.Qxd:Layout 1

THE INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE OF THE BP GROUP ISSUE 4 2011 BPMAGAZINE 32 SPOTLIGHT: AIR BP FIRST CLASS SERVICE +08 BOWMAN’S BP Magazine reports on one of the COUNSEL company’s oldest businesses, BP director learning more about Air BP’s talks safety long-standing relationships and 22 GAS GIANT its plans for the future. Next stage for Shah Deniz 48 TAKING THE LEAD BP supports young leaders Welcome. The founder of the US nuclear navy, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, once said, “You contents / issue 4 2011 don’t get what you expect. You get what you + Features inspect.” According to Admiral Frank ‘Skip’ 08 Safe hands Skip Bowman, one of BP’s non-executive directors, Bowman, a former director of the nuclear talks about his 38 years in the US Navy, and what safety means to him. submarine and carrier fleets and now non- By David Vigar Photography by Graham Trott executive director of BP, it is a principle that BP is 15 Turning point A summary of the work BP has done in 2011 on now implementing throughout its businesses. safety, restoring trust and pursuing growth in shareholder value, as well as its 10-point plan for the future. Photography by BP Imageshop He talks about his 38-year career in the US Navy and its legendary reputation in the world of 22 High rise The Baku skyline is changing rapidly, thanks to the revenues being generated by Azerbaijan’s oil and gas industry. BP’s role safety and risk management (page 8). He’s not in that is about to expand, with plans to develop the full Shah Deniz the only one with a long career behind him. -

Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council Held on 3 December 2008

Manchester City Council Minutes of a Special Meeting of the Council held on 3 rd December 2008 Present: The Right Worshipful, The Lord Mayor Councillor Mavis Smitheman – In the Chair Councillors Amesbury, Andrews, Ankers Ashley, J. Battle, Bethell, Bhatti, Boyes, Bracegirdle, Burns, Cameron, Carmody, Chohan, Chowdhury, Clayton, Commons, Cooley, Cooper, Cowan, Cowell, Cox, Curley, Dobson, Donaldson, Eakins, Evans, Fairweather, Fender, Fisher, Firth, Flanagan, Glover, Grant, Hackett, Harrison, Hassan, Helsby, Isherwood, Jones, Judge, Karney, Keegan, Keller, A. Khan, M. Khan, Kirkpatrick, Leese, Lewis, Lomax, Longsden, Loughman, Lyons, McCulley, M. Murphy, N. Murphy, P. Murphy, S. Murphy, E. Newman S. Newman, O’Callaghan, O’Connor, Barbara O'Neil, Brian O’Neil, Pagel, Parkinson, Pearcey, Priest, Pritchard, Rahman, Ramsbottom, Risby, Royle, Ryan, Sandiford, Shaw, Siddiqi, Smith, Stevens, Swannick, Trotman, Walters, Watson and Whitmore. Also Present: Honorary Aldermen Audrey Jones and John Smith. CC/08/82 Death of Councillor Neil Trafford The Lord Mayor formally recorded the sudden and tragic death of Councillor Neil Trafford as a result of a road traffic accident on Sunday 23 rd November. The Council recalled that Neil had served as Liberal Democrat Councillor for the Barlow Moor and Didsbury West Wards since 2003. He was an active Committee member and an acccomplished political campaigner across the North West of England. The Lord Mayor said that the generous tributes paid to him in public forums and numerous websites in recent days was perhaps the clearest testimony to the very high regard in which he was held in many different fields of activity. In a short life she said that he had clearly achieved much and members were left to wonder what more he might have contributed in the future. -

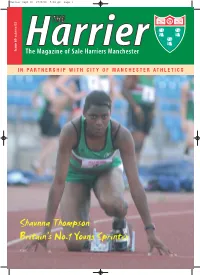

Harrier Sept 08 27/8/08 5:04 Pm Page 1 THE

Harrier Sept_08 27/8/08 5:04 pm Page 1 THE autumn O8 Harrier Issue 69 The Magazine of Sale Harriers Manchester IN PARTNERSHIP WITH CITY OF MANCHESTER ATHLETICS Shaunna Thompson Britain’s No.1 Young Sprinter Harrier Sept_08 27/8/08 5:04 pm Page 2 Produced 4 times a year At Your Service Editorial for 13 years EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE FECHIN McCORMICK PRESIDENT: Mr ERIC HUGHES, Those Beijing Olympics? They’re going 8 NORRIS ROAD, SALE, MANCHESTER M33 3GN. to be a hard act to follow – the Chinese have certainly set the bar pretty high. Tel: 0161 998 1526 (work) 0161 973 5477 (home) Those two thrilling weeks in August Mobile: 07899 891070. E-mail: [email protected] (work) may already be fading but how they CHAIRMAN: Mr DAVID BROWN C.B.E. 48 PARK AVENUE, momentarily made us forget the dismal SALE M33 6HE. Tel:0161 969 5547. E-mail: [email protected] summer. Remember! We even stopped talking about the housing crisis and the VICE-CHAIRMAN: BRYAN GANE, 5 LINDEN WAY, HIGH LANE, start of another soccer season went STOCKPORT, SK6 8ET. Tel:01663 764820. almost unnoticed. We had only one E-mail: [email protected] thing on our minds – Gold; golds for cycling, golds for rowing, golds for HON SECRETARY: MRS CAROL BROWN, sitting, and – quashing the myth that 48 PARK AVENUE, SALE M33 6HE. Tel:0161 969 5547. Brits can only win sitting down – we E-mail: [email protected] even got a gold for running. It's such a pity than none of our three HON FINANCE: MR ROY SWINBANK, 97 GREENHILL ROAD, BURY, representatives returned with a piece of that precious metal but let's not forget LANCS BL8 2LL. -

A Study on Summarizing and Evaluating Long Documents

A Study on Summarizing and Evaluating Long Documents Anonymous ACL submission Abstract code the input sequence into a single vectorial rep- 040 resentation and another RNN to extract the target 041 001 Text summarization has been a key language sequence. This approach allowed the generation 042 002 generation task for over 60 years. The field of sequences of arbitrary length conditioned upon 043 003 has advanced considerably during the past an input document and therefore was adopted by 044 004 two years, benefiting from the proliferation of 005 pre-trained Language Models (LMs). How- the summarization community as the first viable 045 006 ever, the field is constrained by two fac- attempt at abstractive summarization (e.g. (See 046 007 tors: 1) the absence of an effective auto- et al., 2017), (Nallapati et al., 2016)). The pace 047 008 matic evaluation metric and 2) a lack of ef- of progress further accelerated leveraging trans- 048 009 fective architectures for long document sum- formers (Vaswani et al., 2017) as these are able to 049 010 marization. Our first contribution is to demon- generate outputs with higher fluency and coherence 050 011 strate that a set of semantic evaluation metrics than was previously possible. This improvement in 051 012 (BERTScore, MoverScore and our novel met- performance drove a push into a wider and more 052 013 ric, BARTScore) consistently and significantly 014 outperform ROUGE. Using these metrics, we diversified range of datasets, broadening from sum- 053 015 then show that combining transformers with marizing short news articles (e.g. (Hermann et al., 054 016 sparse self-attention is a successful method for 2015), (Narayan et al., 2018)) to generating news 055 017 long document summarization and is competi- headlines (Rush et al., 2015), longer scientific docu- 056 018 tive with the state of the art. -

Welsh Athletics Milestones

Welsh Athletics Milestones Recalled by Clive Williams 1860 John Chambers holds a sports meeting at Hafod House, Aberystwyth - probably the first record of an athletics meeting being held in Wales 1865 Chambers organises “athletic sports” at Aberystwyth. 1865 William Richards, born in “Glamorgan” sets a world record for the mile with 4 mins. 17 ¼ seconds. 1871 St. David’s College Lampeter and Llandovery College hold athletics “sports” meetings. 1875 Newport Athletic Club formed and holds “athletic sports.” 1877 Cardiff-born William Gale achieves the phenomenal deed of walking 1,500 miles in 1,000 hours. He was the world’s leading pedestrian. 1879 Llanfair Caereinion Powys-born George Dunning sets a world 40 miles record at Stamford Bridge of 4:50.12. 1880 Newport AC represented by Richard Mullock at the formation of the AAA at The Randolph Hotel, Oxford - Chambers also there. 1881 Dunning effectively sets an inaugural world record for the half-marathon when he runs 1:13.46 on a track at Stamford Bridge. The distance is actually 13 miles 440 yards, i.e. further than the designated half marathon distance of 13 miles 192.5 yards. 1881 Dunning becomes the first Welsh born athlete to win the (English) National cross country title. 1882 Roath (Cardiff) Harriers formed. They amalgamated with Birchgrove (Cardiff) Harriers in 1968 to form Cardiff AAC.1890. 1890 Will Parry, born in Buttington, near Welshpool wins the (English) National cross country title for a third successive year. 1893 First Welsh amateur track championships held as part of an open sports meeting. Just 2 events held - 100 yards and mile won by Charles Thomas (Reading AC) and Hugh Fairlamb (Roath). -

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men's 200M by K Ken Nakamura

2013 World Championships Statistics – Men’s 200m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Moskva: 1) Nobody won 100m/200m double at the Worlds more than once. Can Bolt do it for the second time? 2) Can Bolt win 200m for the third time to surpass Michael Johnson and Calvin Smith? 3) No country other than US ever won multiple medals in this event. Can Jamaica do it? 4) No European won medal at both 100m and 200m? Can Lemaitre change that? All time Performance List at the World Championships Performance Performer Time Wind Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 19.19 -0.3 Usain Bolt JAM 1 Berlin 2009 2 19.40 0.8 Usain Bolt 1 Daegu 2011 3 2 19.70 0.8 Walter Dix USA 2 Daegu 2011 4 3 19.76 -0.8 Tyson Gay USA 1 Osaka 2007 5 4 19.79 0.5 Michael Johnson USA 1 Göteborg 1995 6 5 19.80 0.8 Christophe Lemaitre FRA 3 Daegu 2011 7 6 19.81 -0.3 Alonso Edward PAN 2 Berlin 2009 8 7 19.84 1.7 Francis Obikwelu NGR 1sf2 Sevilla 1999 9 8 19.85 0.3 Frankie Fredericks NAM 1 Stuttgart 1993 9 9 19.85 -0.3 Wallace Spearmon USA 3 Berlin 2009 11 10 19.89 -0.3 Shawn Crawford USA 4 Berlin 2009 12 11 19.90 1.2 Maurice Greene USA 1 Sevilla 1999 13 19.91 -0.8 Usain Bolt 2 Osaka 2007 14 12 19.94 0.3 John Regis GBR 2 Stuttgart 1993 15 13 19.95 0.8 Jaysuma Saidy Ndure NOR 4 Daegu 2011 16 14 19.98 1.7 Marcin Urbas POL 2sf2 Sevilla 1999 16 15 19.98 -0.3 Steve Mullings JAM 5 Berlin 2009 17 16 19.99 0.3 Carl Lewis USA 3 Stuttgart 1993 19 17 20.00 1.2 Claudinei da Silva BRA 2 Sevilla 1999 19 20.00 -0.4 Tyson Gay 1sf2 Osaka 2007 21 20.01 -3.4 Michael Johnson 1 Tokyo 1991 21 20.01 0.3 -

Doctors of Naturopathy, Homeopathy, Ayurveda and Medical Qigong

International Appeal to Stop 5G on Earth and in Space DOCTORS OF NATUROPATHY, HOMEOPATHY, AYURVEDA AND MEDICAL QIGONG ARGENTINA CELSA RITA BRUENNER , Médica Tocoginecologa y Homeopata, CORDOBA, CORDOBA Marina Caride , Buenos aires, Buenos Aires Alejandro Cortiglia , Doctor, Lujan, Buenos Aires Aman Diaz , Terciario, Mar del plata, Bs As AUSTRALIA Sarah Acheson , Adv Dip Naturopathy, Perth, TAS Tanya Adams , Advanced diploma, Naturopathy, Health, Buderim, Qld Rachel Aldridge , Bachelor of Commerce, Masters of Marketing, Adv diploma Naturopathy, Naturopath, Baulkham Hills, NSW Nena Aleschewski , Glenorchy, Tasmania Paul Alexander , N.D., Naturopath, MT.HAWTHORN, WA Samantha Allan , BHSc, Traralgon, Victoria Val Allenl , ND, Perth, Western Australia Steven Bartlett , Diploma in Health Science, Master Ayurvedic Diploma and others., Naturopath, Maleny, Queensland Maria Bass , Melbourne, Victoria Susi Baumgartner , Melbourne, Victoria Llewanna Bell , Advance diploma of applied science, Perth, WA Brigitte Bennett , Adv. Diploma of Naturopathy, Melbourne, VIC Tanya Bentley , RAVENSHOE, Queensland Rebecca Bibbens , Bachelor of Health Science, Naturopath, Canberra, ACT Manon Bocquet , Bachelor Health Science, Scarborough, Western Australia Nara-Beth Bonfiglio , Clinical nutritionist., Helena valley, WA julia boon , billinudgel, NSW matarisvan boon , billinudgel, NSW Glenyss Bourne , Diploma of Naturopathy (ND), Naturopath and Energy healer, Frankston, Victoria Jewels Bowering , Health care/ parent, Sydney, Blackheath Zoe Boyce , Bachelor in Early