The Writings of Eloise Butler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Plant List Index: Trees & Shrubs Pg

2020 Plant List Index: Trees & Shrubs pg. 2-7 Perennials pg. 7-13 Grasses pg. 14 Ferns pg. 14-15 Vines pg. 15 Hours: May 1 – June 30: Tues.- Sat. 10 am - 6 pm Sun.11 am - 5 pm 3351 State Route 37 West www.sciotogardens.com On Mondays by appointment Delaware, OH 43015 Phone/fax: 740-363-8264 Email: [email protected] Sustainable, earth-friendly growth and maintenance practices: Real Soil = Real Difference. All plants are container-grown in a blend of local soil and compost. Plants are grown outside year-round. They are always in step with the seasons. Minimal pruning ensures a well-rooted, healthy plant. Use degradableRoot Pouch andcontainers. recycled containers to reduce waste. Use of controlled-release fertilizers minimizes leaching into the environment. Our primary focus is on native plants. However, non-invasive exotics are an equally important part of the choices we offer you. There is great creative opportunity using natives in combination with exotics. Adding more native plants into our landscapes provides food and habitat for wildlife and connections to larger natural areas. AdditionalAdditional species species may may be be available. available. Email Email oror call for currentcurrent availability, availability, sizes, sizes, and and prices. prices. «BOT_NAME» «BOT_NAME»Wetland Indicator Status—This is listed in parentheses after the common name when a status is known. All species «COM_NAM» «COM_NAM» «DESCRIP»have not been evaluated. The indicator code is helpful in evaluating«DESCRIP» the appropriate habitat for a -

Vascular Plants for High Park and the Surrounding Humber Plains, 2008

Annotated Checklist of the Vascular Plants for High Park and the Surrounding Humber Plains September 2008 Steve Varga Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Aurora District Acknowledgements The Ministry has undertaken biological inventories of High Park and its environs over the past 32 years. The first botanical survey was carried out by Karen L. McIntosh as part of an ecological survey of High Park that focussed on Grenadier Pond and the surrounding uplands (Wainio et al. 1976). Botanical surveys were also carried out by the author in 1980, 1982 and 1988. In 1989, this survey information was put together into an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) inventory report of the Park that recognized the natural areas of High Park as a provincial life science ANSI. Subsequent botanical surveys were carried out by the author between 1997 and 2008. Botanical records from High Park have also been kindly provided by Dr. Paul. M. Catling, Dr. Paul F. Maycock, Roger Powley, Charles Kinsley, Gavin Miller, Bohdan Kowalyk, Diana Banville and other members of the Toronto Field Naturalists (TFN), City of Toronto Parks, Forestry & Recreation Division including present and former staff such as Terry Fahey, Cara Webster and Richard Ubens among others, the High Park Community Advisory Committee and it Natural Environment Committee chaired by Karen Yukich, and James Kamstra who in 2007 and 2008 is mapping the location and numbers of rare plants in the Park. The Vascular Plant Herbarium (TRT) at the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto, Erindale College Herbarium (TRTE) were also examined for historical and recent records from the Park and its surrounding areas. -

Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments Contributors: Printing was made possible through the generous funding from Adkins Arboretum; Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management; Chesapeake Bay Trust; Irvine Natural Science Center; Maryland Native Plant Society; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; The Nature Conservancy, Maryland-DC Chapter; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Reviewers: species included in this guide were reviewed by the following authorities regarding native range, appropriateness for use in individual states, and availability in the nursery trade: Rodney Bartgis, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Ashton Berdine, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Chris Firestone, Bureau of Forestry, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Chris Frye, State Botanist, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Mike Hollins, Sylva Native Nursery & Seed Co. William A. McAvoy, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Mary Pat Rowan, Landscape Architect, Maryland Native Plant Society. Rod Simmons, Maryland Native Plant Society. Alison Sterling, Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources. Troy Weldy, Associate Botanist, New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Graphic Design and Layout: Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Special thanks to: Volunteer Carole Jelich; Christopher F. Miller, Regional Plant Materials Specialist, Natural Resource Conservation Service; and R. Harrison Weigand, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Division for assistance throughout this project. -

Enhancing the Edibility of Landscapes with Native Species

Enhancing the Edibility of Landscapes with Native Species Presented by Russ Cohen at the 2013 RI Land and Water Conservation Summit Saturday, March 9, at the URI Memorial Union, Kingston, RI Flowering Raspberry (Rubus odoratus) in bloom Ripe Butternuts (Juglans cinerea) in their husks •There has been a burgeoning interest in recent years in restoring native plants to our gardens, yards and landscapes (e.g., as evidenced by the 2010 formation of the group Grow Native Massachusetts). •This movement got a major boost several years ago from the publication of the book Bringing Nature Home: How Native Plants Sustain Wildlife in our Gardens. •In Bringing Nature Home, author and University of Delaware Entomology Professor Doug Tallamy makes a compelling case for the key role that native plant species play in supporting our native species of wildlife, particularly insects (such as butterflies and moths), which (in addition to their intrinsic value) serve as a major source of nourishment for nestling birds. Volunteers planting native plant species along the banks of the Housatonic River in Great Barrington, MA A few examples of outreach materials intended to promote and facilitate the planting of native species -- Recommended Native Species for Planting in Lexington, MA National Wildlife Federation’s Community Wildlife Habitat Program Mass. Coastal Zone Management’s Coastal Landscaping with Native Species Excerpt from Rhode Island Coastal Plant Guide – while extremely informative and user-friendly, note the lack of an “edible by humans” column -

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees For

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Betula populifolia Gray Birch 30' Juniperis virginiana Eastern Red Cedar 10-75' Pinus resinosa Red Pine 70' Pin us rigida Pitch Pine 50' Pinus stro bus White Pine 80' Quercus rubra Red Oak 70' Quercus coccinea Scarlet Oak 70' Quercus velutina Black Oak 70' Shrubs for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name 'Common Name Mature Height Amelanchier canadensis Shadbush 15' Ceanothus americanus New Jersey Tea 4' Comptonia peregrina Sweetfern 4' Cornus racemosa Gray Dogwood 6-10' Gaylussacia baccata Black Huckleberry l' Hypericum prolificum Shrubby St. Johnswort 4' Juniperus communis Pasture Juniper 2' Myrica pensylvanica Bayberry 6' Prunus maritima Beach plum 6' Rhus aromatica Fragrant Sumac 3' Rhus copallina Shining Sumac 4-10' Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac 9-15' Rosa carolina Pasture Rose 3' Rosa virginiana Virginia Rose 3' Spirea tomentosa Steeplebush 3-4' Viburnum dentatum/recognitum Arrowwood 5-8' Viburnum lentago Nannyberry 15' Shrubs For Dry-Shady Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Hamamelis wrginiana Witch Hazel 15' Kalmia latifolia Mountain Laurel 3-8' Rhododendron nudiflorum Pinxterbloom Azalea 4-6' Vaccinium angustifolium Lowbush Blueberry 2' Viburnum dentatum Arrowwood 5-8' Trees For Moist Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Acer rubrum Red Maple 60' Betula nigra River Birch Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash 60' Picea mariana Black Spruce 40' Picea -

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration

Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Environmental Horticulture University of Washington 2013 Committee: Linda Chalker-Scott Kern Ewing Sarah Reichard Joshua Chenoweth Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Environmental and Forest Sciences Guidebook to Invasive Nonnative Plants of the Elwha Watershed Restoration Olympic National Park, Washington Cynthia Lee Riskin Master of Environmental Horticulture candidate School of Environmental and Forest Sciences University of Washington, Seattle September 3, 2013 Contents Figures ................................................................................................................................................................. ii Tables ................................................................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... vii Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Bromus tectorum L. (BROTEC) ..................................................................................................................... 19 Cirsium arvense (L.) Scop. (CIRARV) -

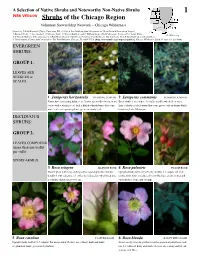

Shrubs of the Chicago Region

A Selection of Native Shrubs and Noteworthy Non-Native Shrubs 1 WEB VERSION Shrubs of the Chicago Region Volunteer Stewardship Network – Chicago Wilderness Photos by: © Paul Rothrock (Taylor University, IN), © John & Jane Balaban ([email protected]; North Branch Restoration Project), © Kenneth Dritz, © Sue Auerbach, © Melanie Gunn, © Sharon Shattuck, and © William Burger (Field Museum). Produced by: Jennie Kluse © vPlants.org and Sharon Shattuck, with assistance from Ken Klick (Lake County Forest Preserve), Paul Rothrock, Sue Auerbach, John & Jane Balaban, and Laurel Ross. © Environment, Culture and Conservation, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [http://www.fmnh.org/temperateguides/]. Chicago Wilderness Guide #5 version 1 (06/2008) EVERGREEN SHRUBS: GROUP 1. LEAVES ARE NEEDLES or SCALES. 1 Juniperus horizontalis TRAILING JUNIPER: 2 Juniperus communis COMMON JUNIPER: Plants have a creeping habit; some leaves are needles but most are Erect shrub or tree (up to 3 m tall); needles whorled on stem; scales with a whitish coat; fruit a bluish-whitish berry-like cone; fruit a bluish or black berry-like cone; grows only in dunes/bluffs male cones on separate plants; grows in sandy soils. bordering Lake Michigan. DECIDUOUS SHRUBS: GROUP 2. LEAVES COMPOUND (more than one leaflet per stalk). STEMS ARMED. 3 Rosa setigera ILLINOIS ROSE: 4 Rosa palustris SWAMP ROSE: Mature plant with long-arching stems; sparse prickles; leaflets Upright shrub; stems very thorny; leaflets 5-7; sepals fall from usually 3, but sometimes 5; styles (female pollen tube) fused into mature fruit; fruit smooth, red berry-like hips; grows in wet and a column; stipules narrow to tip. open ditches, bogs, and swamps. -

Great Lakes Bluff Seep System: Palustrine Subsystem: Shrubland

Great Lakes Bluff Seep System: Palustrine Subsystem: Shrubland PA Ecological Group(s): Great Lakes Region Wetland Global Rank: GNR State Rank: S1 General Description The bluff face communities are characteristically open with a mixture of shrubs and sometimes with scattered trees. This is a very dynamic system and the structure of the vegetation depends largely on its successional status. Recently slumped areas are first colonized by bryophytes and Equisetum spp. (horsetails). As the substrate becomes more stable, and organic matter accumulates, graminoids, other herbs, and shrubs colonize the seep. Eventually, due to erosion from below and perhaps also because of the weight of the vegetation and organic matter, the entire community will slump or slide downslope and the cycle begins again. Physiognomic differences generally reflect different seral stages in this dynamic system. Common trees and woody species include shadbush (Amelanchier arborea), Canada hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides), hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), round-leaved dogwood (Cornus rugosa), red-osier dogwood (C. sericea), alternate-leaved dogwood (C. alternifolia), speckled alder (Alnus incana), spicebush (Lindera benzoin), purple-flowering raspberry (Rubus odoratus) willows (Salix spp.), and staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina). Herbaceous species include zigzag goldenrod (Solidago flexicaulis), jewelweed (Impatiens pallida), field horsetail (Equisetum arvense), grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca), golden ragwort (Packera aurea), fowl mannagrass (Glyceria striata), golden-fruited sedge (Carex aurea) and brook lobelia (Lobelia kalmii). Exotic species include common reed (Phragmites australis), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), and colt’s foot (Tussilago farfara). Rank Justification Critically imperiled in the state because of extreme rarity or because of some factor(s) making it especially vulnerable to extirpation from the state. -

Wildflowers and Ferns Along the Acton Arboretum Wildflower Trail and in Other Gardens FERNS (Including Those Occurring Naturally

Wildflowers and Ferns Along the Acton Arboretum Wildflower Trail and In Other Gardens Updated to June 9, 2018 by Bruce Carley FERNS (including those occurring naturally along the trail and both boardwalks) Royal fern (Osmunda regalis): occasional along south boardwalk, at edge of hosta garden, and elsewhere at Arboretum Cinnamon fern (Osmunda cinnamomea): naturally occurring in quantity along south boardwalk Interrupted fern (Osmunda claytoniana): naturally occurring in quantity along south boardwalk Maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum): several healthy clumps along boardwalk and trail, a few in other Arboretum gardens Common polypody (Polypodium virginianum): 1 small clump near north boardwalk Hayscented fern (Dennstaedtia punctilobula): aggressive species; naturally occurring along north boardwalk Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum): occasional along wildflower trail; common elsewhere at Arboretum Broad beech fern (Phegopteris hexagonoptera): up to a few near north boardwalk; also in rhododendron and hosta gardens New York fern (Thelypteris noveboracensis): naturally occurring and abundant along wildflower trail * Ostrich fern (Matteuccia pensylvanica): well-established along many parts of wildflower trail; fiddleheads edible Sensitive fern (Onoclea sensibilis): naturally occurring and abundant along south boardwalk Lady fern (Athyrium filix-foemina): moderately present along wildflower trail and south boardwalk Common woodfern (Dryopteris spinulosa): 1 patch of 4 plants along south boardwalk; occasional elsewhere at Arboretum Marginal -

Tennessee's Native Plant Alternatives To

his brochure lists the exotic plants to avoid and Tennessee’s Native Plant Alternatives to the attractive native alternatives that will work Tjust as well. The list features those invasive plants Exotic Invasives A Garden & Landscape Guide often considered for home gardens and landscaping, their state ranking as a pest, and their qualities typically on-native plants that readily spread in natural areas, either vegetatively or via seed, pose considered ornamental or useful. Adjacent to each is one a significant threat to the health and welfare of Tennessee’s rich biological diversity. !ese or more suggested native plant alternatives along with N plants are considered exotic invasive pests. their desirable aesthetic or practical characteristics as a suitable replacement, the availability of cultivars, and their Invasive plants exhibit certain traits. wildlife value. • Adaptation to local climate Native Plant Sources Please support local nurseries • Rapid growth carrying nursery-propagated native plants—stock • Mature quickly to flower and set seed supplied through seed, division or tissue culture of • Produce copious amounts of seed existing nursery plants and not collected from the wild. • Effective seed dispersal Tennessee Exotic Pest Plant Council • Rampant vegetative spread The exotic invasive plants in this brochure came from a • No major pest or disease problems larger list compiled by the Tennessee Exotic Pest Plant These traits can give exotic invasive plants undue advantage in wild habitats like forests, Council, a group of scientists and public land managers wetlands, cedar glades, and grasslands. Exotic species can overwhelm native plants by who monitor plant communities in the state. TNEPPC depriving them of nutrients, water, light, and space and may totally displace native species, ranks each plant according to its degree of invasiveness replacing a diverse ecosystem with a near sterile monoculture. -

Rosa Palustris Marshall Common Names: Swamp Rose, Marsh Rose (1,11)

Rosa palustris Marshall Common Names: Swamp rose, marsh rose (1,11). Etymology: Rosa is the Latin word for ‘rose’, and palustris means ‘of marshes’ (8,9), indicating the species preference for wet habitats. Botanical synonyms (4): Rosa floridana Rydb. Rosa lancifolia Small FAMILY: Rosaceae (the Rose family) Quick Notable Features (1,6,9): ¬ Hispid-glandular pink flowers ¬ Infrastipular prickles are hooked & broad-based ¬ Arching or erect armed stems with alternate leaves & 5-9 leaflets with finely serrate margins ¬ Stipules are mostly adnate, revolute, with divergent apices, with margins entire Plant Height: R. palustris is capable of climbing 2-3 meters high (C.V.S., pers. obs.). Subspecies/varieties recognized (3): R. palustris var. aculeata (Schuette) Erlanson R. palustris var. dasistema (Raf.) E.J. Palmer & Steyerm. R. palustris var. inermis (Regel) Erlanson Most Likely Confused with: Rosa multiflora, R. canina, R. carolina, R. virginiana, R. setigera, Rubus ssp. especially Rubus odoratus, and Hibiscus moscheutos (rose mallow) Habitat Preference: The swamp rose prefers moist to wet habitats: wetlands, riparian zones, swales, and ponds edges. It thrives in full or partial sun (1,4). The habitat specificity is very helpful when identifying this species. Geographic Distribution in Michigan: R. palustris is common throughout the state, found in 68 of 83 counties. The counties with no record for the species are Saginaw, Isabella, Osceola, Gladwin, Arenac, Missaukee, Iosco, Crawford, Oscoda, Alcona, Montmorency, Alpena, Dickinson, Iron, and Gogebic (1). 1 Known Elevational Distribution: In Reynolds, MO, the swamp rose is found up to 317m above sea level (3). Complete Geographic Distribution: Native to North America. -

1 a Life History Analysis of Invasive Behavior in Native and Naturalized

A Life History Analysis of Invasive Behavior in Native and Naturalized Species: Rubus odoratus and Rubus allegheniensis in the Nichols Arboretum, Ann Arbor, MI Mita Nagarkar University of Michigan Program in the Environment Honors Thesis 1 Acknowledgements: I received immeasurable support throughout the process of writing this thesis. A resounding thank you goes to Professor Bob Grese who gave me access to his immense knowledge of plants and ecosystem management and to Professor Bobbi Low for her expertise with statistics and life history theory. These two people inspired me to make the most of this experience. I would also like to thank Professor Inez Ibanez for allowing me access to her lab. I am grateful to the Nichols Arboretum, Matthaei Botanical Gardens, Bentley Historical Library and the University of Michigan Herbarium for the resources and help which they provided me. No less important was the support of Shelby Goss and Gorgin Rezvani who kept me sane and put up with my endless talk about raspberries and blackberries. Thank you for your invaluable feedback and for allowing me to bounce my ideas off you. I could not have done this without you guys. Finally, a big thank you to my family and friends for their support and for never questioning why there were raspberry seeds in the blender. 2 Abstract: Invasive species are defined broadly as “non-indigenous species or strains that become established in natural plant communities and wild areas and replace native vegetation” (Czarapata, 2005). Based on my own recent research as well as the data reviewed in this paper, I argue that this definition is limiting in the context of climate change and globalization.