Essential Guide to Rubus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Diversity in Wild and Cultivated Black Raspberry (Rubus Occidentalis L.) Evaluated by Simple Sequence Repeat Markers

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska 2012 Genetic diversity in wild and cultivated black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) evaluated by simple sequence repeat markers Michael Dossett Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre Nahla V. Bassil United States Department of Agriculture Kim S. Lewers United States Department of Agriculture Chad E. Finn United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Dossett, Michael; Bassil, Nahla V.; Lewers, Kim S.; and Finn, Chad E., "Genetic diversity in wild and cultivated black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) evaluated by simple sequence repeat markers" (2012). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 1243. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/1243 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Genet Resour Crop Evol (2012) 59:1849–1865 DOI 10.1007/s10722-012-9808-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity in wild and cultivated black raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) evaluated by simple sequence repeat markers Michael Dossett • Nahla V. Bassil • Kim S. Lewers • Chad E. Finn Received: 7 September 2011 / Accepted: 15 January 2012 / Published online: 26 February 2012 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht (outside the USA) 2012 Abstract Breeding progress in black raspberry (Ru- (SSR), markers are highly polymorphic codominant bus occidentalis L.) has been limited by a lack of markers useful for studying genetic diversity, popula- genetic diversity in elite germplasm. -

Analysis of Flavonoids in Rubus Erythrocladus and Morus Nigra Leaves Extracts by Liquid Chromatography and Capillary Electrophor

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia 25 (2015) 219–227 www.sbfgnosia.org.br/revista Original Article Analysis of flavonoids in Rubus erythrocladus and Morus nigra leaves extracts by liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis a a b c Luciana R. Tallini , Graziele P.R. Pedrazza , Sérgio A. de L. Bordignon , Ana C.O. Costa , d e a,∗ Martin Steppe , Alexandre Fuentefria , José A.S. Zuanazzi a Departamento de Produc¸ ão de Matéria Prima, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil b Centro Universitário La Salle, Canoas, RS, Brazil c Departamento de Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil d Departamento de Produc¸ ão e Controle de Medicamentos, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil e Departamento de Análises, Faculdade de Farmácia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil a a b s t r a c t r t i c l e i n f o Article history: This study uses high performance liquid chromatography and capillary electrophoresis as analytical tools Received 15 January 2015 to evaluate flavonoids in hydrolyzed leaves extracts of Rubus erythrocladus Mart., Rosaceae, and Morus Accepted 30 April 2015 nigra L., Moraceae. For phytochemical analysis, the extracts were prepared by acid hydrolysis and ultra- Available online 17 June 2015 sonic bath and analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography using an ultraviolet detector and by capillary electrophoresis equipped with a diode-array detector. Quercetin and kaempferol were iden- Keywords: tified in these extracts. The analytical methods developed were validated and applied. -

Cally Plant List a ACIPHYLLA Horrida

Cally Plant List A ACIPHYLLA horrida ACONITUM albo-violaceum albiflorum ABELIOPHYLLUM distichum ACONITUM cultivar ABUTILON vitifolium ‘Album’ ACONITUM pubiceps ‘Blue Form’ ACAENA magellanica ACONITUM pubiceps ‘White Form’ ACAENA species ACONITUM ‘Spark’s Variety’ ACAENA microphylla ‘Kupferteppich’ ACONITUM cammarum ‘Bicolor’ ACANTHUS mollis Latifolius ACONITUM cammarum ‘Franz Marc’ ACANTHUS spinosus Spinosissimus ACONITUM lycoctonum vulparia ACANTHUS ‘Summer Beauty’ ACONITUM variegatum ACANTHUS dioscoridis perringii ACONITUM alboviolaceum ACANTHUS dioscoridis ACONITUM lycoctonum neapolitanum ACANTHUS spinosus ACONITUM paniculatum ACANTHUS hungaricus ACONITUM species ex. China (Ron 291) ACANTHUS mollis ‘Long Spike’ ACONITUM japonicum ACANTHUS mollis free-flowering ACONITUM species Ex. Japan ACANTHUS mollis ‘Turkish Form’ ACONITUM episcopale ACANTHUS mollis ‘Hollard’s Gold’ ACONITUM ex. Russia ACANTHUS syriacus ACONITUM carmichaelii ‘Spätlese’ ACER japonicum ‘Aconitifolium’ ACONITUM yezoense ACER palmatum ‘Filigree’ ACONITUM carmichaelii ‘Barker’s Variety’ ACHILLEA grandifolia ACONITUM ‘Newry Blue’ ACHILLEA ptarmica ‘Perry’s White’ ACONITUM napellus ‘Bergfürst’ ACHILLEA clypeolata ACONITUM unciniatum ACIPHYLLA monroi ACONITUM napellus ‘Blue Valley’ ACIPHYLLA squarrosa ACONITUM lycoctonum ‘Russian Yellow’ ACIPHYLLA subflabellata ACONITUM japonicum subcuneatum ACONITUM meta-japonicum ADENOPHORA aurita ACONITUM napellus ‘Carneum’ ADIANTUM aleuticum ‘Japonicum’ ACONITUM arcuatum B&SWJ 774 ADIANTUM aleuticum ‘Miss Sharples’ ACORUS calamus ‘Argenteostriatus’ -

Watsonia 27 (2008), 171-187

Watsonia 27: 171–187 (2008) PLANT RECORDS 171 Plant Records Records for publication must be submitted to the appropriate Vice-county Recorder (see BSBI Year Book 2008), and not to the Editors. Following publication of the New Atlas of the British & Irish Flora and the Vice-county Census Catalogue, new criteria have been drawn up for the inclusion of records in Plant Records. (See BSBI News no. 95, January 2004 pp. 10 & 11). These are outlined below: First records of all taxa (species, subspecies and hybrids) included in the VCCC, designated as native, archaeophyte, neophyte or casual. First record since 1970 of the taxa above, except in the case of Rubus, Hieracium and Taraxacum. Records demonstrating the rediscovery of all taxa published as extinct in the VCCC or subsequently. Newly reported definite extinctions. Deletions from the VCCC (e.g. through the discovery of errors, the redetermination of specimens etc.) NB – only those errors affecting VCCC entry. New 10km square records for Rare and Scarce plants, defined as those species in the New Atlas mapped in the British Isles in 100 10km squares or fewer. (See BSBI News no. 95, January 2004 pp. 36–43). Records for the subdivisions of vice-counties will not be treated separately; they must therefore be records for the vice-county as a whole. However, records will be accepted for the major islands in v.cc. 102–104, 110 and 113. In the following list, records are arranged in the order given in the List of Vascular Plants of the British Isles and its supplements by D. -

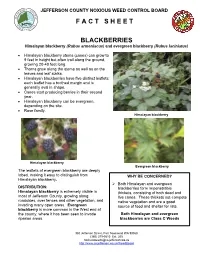

F a C T S H E E T Blackberries

JEFFERSON COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED CONTROL BOARD F A C T S H E E T BLACKBERRIES Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) and evergreen blackberry (Rubus laciniatus) Himalayan blackberry stems (canes) can grow to 9 feet in height but often trail along the ground, growing 20-40 feet long. Thorns grow along the stems as well as on the leaves and leaf stalks. Himalayan blackberries have five distinct leaflets; each leaflet has a toothed margin and is generally oval in shape. Canes start producing berries in their second year. Himalayan blackberry can be evergreen, depending on the site. Rose family. Himalayan blackberry Himalayan blackberry Evergreen blackberry The leaflets of evergreen blackberry are deeply lobed, making it easy to distinguish from WHY BE CONCERNED? Himalayan blackberry. Both Himalayan and evergreen DISTRIBUTION: blackberries form impenetrable Himalayan blackberry is extremely visible in thickets, consisting of both dead and most of Jefferson County, growing along live canes. These thickets out-compete roadsides, over fences and other vegetation, and native vegetation and are a good invading many open areas. Evergreen source of food and shelter for rats. blackberry is more common in the West end of the county, where it has been seen to invade Both Himalayan and evergreen riparian areas. blackberries are Class C Weeds 380 Jefferson Street, Port Townsend WA 98368 (360) 379-5610 Ext. 205 [email protected] http://www.co.jefferson.wa.us/WeedBoard ECOLOGY: . Seeds can be spread by birds, humans and other mammals. The canes often cascade outwards, forming mounds, and can root at the tip when they hit the ground, expanding the infestation . -

Rubus Idaeus (Raspberry ) Size/Shape

Rubus idaeus (raspberry ) Raspberry is an upright deciduous shrub.The shrub has thorns be careful. It ha pinatelly compound leaves with a toothed edge. The plant has two different types of shoots ( canes) One which produces fruits in the given year and one which grows leaves only but will be the next year productive shoot. The fruits are small but very juicy. It grows best in full fun and moderately fertile soil. The best to grow raspberry in a raised bed or in area where any frame or trellis can be put around the plants , otherwise it will fall on the ground. Landscape Information French Name: Framboisier, ﻋﻠﻴﻖ ﺃﺣﻤﺮ :Arabic Name Plant Type: Shrub Origin: North America, Europe, Asia Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Hardiness Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Uses: Screen, Border Plant, Mass Planting, Edible, Wildlife Size/Shape Growth Rate: Fast Tree Shape: Upright Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Plant Image Canopy Density: Medium Canopy Texture: Medium Height at Maturity: 1 to 1.5 m Spread at Maturity: 1 to 1.5 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 2 to 5 Years Rubus idaeus (raspberry ) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Deciduous Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Ovate Leaf Margins: Double Serrate Leaf Textures: Rough Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Flower Image Color(changing season): Brown Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 1.5 - 3 Flower Type: Raceme Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: -

Newsletter 2021 March

NORTH CENTRAL TEXAS N e w s Native Plant Society of Texas, North Central Chapter P Newsletter Vol 33, Number 3 S March 2021 O ncc npsot newsletter logo newsletter ncc npsot © 2018 Troy & Martha Mullens & Martha © 2018 Troy Purple Coneflower — Echinacea sp. T March Program by March 2021 Meeting Mark Morganstern Propagation Techniques for Native Plants Virtual See page 15 Chapter of the Year (2016/17) Chapter Newsletter of the Year (2019/20) Visit us at ncnpsot.org & www.txnativeplants.org Index President's Corner by Gordon Scruggs ..................... p. 3ff Chapter Leaders Flower of the Month, Plains Coreopsis President — Gordon Scruggs by Josephine Keeney ........................................ p. 6f [email protected] Activities & Volunteering for March 2021 by Martha Mullens ....................................... p. 8f Past President — Karen Harden Prairie Verbena by Avon Burton ................................ p. 10 Vice President & Programs — Answer to last month’s puzzle and a new puzzle ...... p. 11 Morgan Chivers March Calendar” Page by Troy Mullens ................... p. 12 Recording Secretary — Debbie Stilson Dewberry by Martha Mullens .................................... p. 13f Treasurer — Position open March Program .............................................................. p. 15 Hospitality Chair — Corinna Benson, Membership Report by Beth Barber .......................... p. 16 Hospitality by Corinna Benson .................................. p. 16 Traci Middleton February Meeting Minutes by Debbie Stilson -

Fuentes Washington 0250E 21

© Copyright 2020 Tracy L. Fuentes Reconstructing Developer and Homeowner Decisions to Understand the Complex Assembly of New Residential Patches and Plant Communities Tracy L. Fuentes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2020 Reading Committee: Marina Alberti, Chair Richard G. Olmstead David R. Montgomery Jan Whittington Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Program in Urban Design and Planning University of Washington Abstract Reconstructing Developer and Homeowner Decisions to Understand the Complex Assembly of New Residential Patches and Plant Communities Tracy L. Fuentes Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Marina Alberti Urban Design and Planning Residential developers and homeowners are urban ecosystem engineers, shaping the structure and function of the residential landscapes, which occupy a large proportion of urban areas. Developers set the template by allocating space to different patch types and by establishing the initial plant communities in new yards. New homeowners then modify these spaces to suit their own preferences, life stages, and neighborhood norms. We know little about how the decisions of developers and homeowners interact to create the residential land covers. To document initial conditions of single family residential landscapes, I recruited a stratified random sample of 60 homeowners who had purchased a newly built home in the lower Green-Duwamish watershed of the Seattle Metropolitan Statistical Area in Washington State in 2014 or 2015. Through field sampling, aerial photo interpretation, conversations with the new homeowners, and archival photo research, I reconstructed the decisions of the developers and new homeowners. By taking a patch mosaic and plant community approach, I showed that urban form and economic considerations shape developer and homeowner decisions. -

'Sanna' Lingonberry Derived by Micropropagation Vs. Stem Cuttings

PROPAGATION & TISSUE CULTURE HORTSCIENCE 35(4):742–744. 2000. (WPM) (Lloyd and McCown, 1980) contain- ing 30 g·L–1 sucrose and 5 mg·L–1 2-isopentenyl adenine (2iP) before being rooted (in the same Field Performance of ‘Sanna’ medium as SC plants) in the greenhouse with high humidity and artificial light (long day) in Lingonberry Derived by Winter 1993–94. No rooting compound was applied to either the TC or the SC plants. Well- Micropropagation vs. Stem Cuttings rooted and approximately similar-sized pot plants from both propagation sources were Björn A. Gustavsson transplanted in Fall 1994 from the nursery to an experimental field at Balsgård (56°7´N, Balsgård–Department of Horticultural Plant Breeding, S–291 94 Kristianstad, 14°10´E). The soil in this field is a low-fertil- Sweden ity, sandy moraine, pH 5.6. Plants were grown in one row with three blocks of 10 plants each Vidmantas Stanys for a total of 30 plants per propagation method, Lithuanian Institute of Horticulture, 4335 Babtai, Kaunas District, Lithuania at a spacing of 40 cm. The field was mulched with 3–4 cm milled Additional index words. Vaccinium, cowberry, mountain cranberry, tissue culture, fruiting, peat 1 year after planting, and broadcast fertil- rhizomes ized each spring with 200 kg·ha–1 Complesal Abstract. Field performance in lingonberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. cv. Sanna) was (Hoechst, Lomma, Sweden) 12N–5P–14K. compared in 1995–97 for plants produced by tissue culture (TC) vs. stem cuttings (SC). Pot Irrigation was provided only in periods with plants of about the same size were transplanted from the nursery to an infertile, sandy prolonged lack of precipitation. -

Rubus Fruticosus L.: Constituents, Biological Activities and Health Related Uses

Molecules 2014, 19, 10998-11029; doi:10.3390/molecules190810998 OPEN ACCESS molecules ISSN 1420-3049 www.mdpi.com/journal/molecules Review Rubus Fruticosus L.: Constituents, Biological Activities and Health Related Uses Muhammad Zia-Ul-Haq 1,*, Muhammad Riaz 2, Vincenzo De Feo 3, Hawa Z. E. Jaafar 4,* and Marius Moga 5 1 The Patent Office, Kandawala Building, M.A. Jinnah Road, Karachi-74400, Pakistan 2 Department of Pharmacy, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal, Dir Upper-2500, Pakistan; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences, University of Salerno, Salerno 84100, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Crop Science, Faculty of Agriculture, University Putra Malaysia, Selangor, 43400, Malaysia; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Department of Medicine, Transilvania University of Brasov, Brasov 500036 Romania; E-Mail: [email protected] * Authors to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mails: [email protected] (M.Z.-U.-H.); [email protected] (H.Z.E.J.); Tel.: +92-322-250-6612 (M.Z.-U.-H.); +6-03-8947-4821 (H.Z.E.J.); Fax: +6-03-8947-4918 (H.Z.E.J.). Received: 21 April 2014; in revised form: 14 July 2014 / Accepted: 16 July 2014 / Published: 28 July 2014 Abstract: Rubus fruticosus L. is a shrub famous for its fruit called blackberry fruit or more commonly blackberry. The fruit has medicinal, cosmetic and nutritive value. It is a concentrated source of valuable nutrients, as well as bioactive constituents of therapeutic interest highlighting its importance as a functional food. Besides use as a fresh fruit, it is also used as ingredient in cooked dishes, salads and bakery products like jams, snacks, desserts, and fruit preserves. -

A Palynological Investigation of Louisiana Honeys. Meredith Elizabeth Hoag Lieux Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 A Palynological Investigation of Louisiana Honeys. Meredith Elizabeth hoag Lieux Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Lieux, Meredith Elizabeth hoag, "A Palynological Investigation of Louisiana Honeys." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1675. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1675 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-9075 LIEUX, Meredith Elizabeth Hoag, 1939- A PALYNOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF LOUISIANA HONEYS. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1969 Botany University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (c) Meredith Elizabeth Hoag Lieux 1970. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED A PALYNOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF LOUISIANA HONEYS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Botany and Plant Pathology by Meredith Elizabeth Hoag Lieux B.S., Louisiana State University,.1960 M.S., University of Mississippi, 1964 August, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sincere appreciation is expressed to Dr. Clair A. Brown for his assistance and guidance throughout this study. I especially wish to recognize and again thank him for his work on the photographs used in m y manuscript and for the reference pollen that he made available to me. -

Transcriptome Assembly and Expression Analysis in Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides-Tolerant Rubus 7 Glaucus Benth

RESEARCH Transcriptome assembly and expression analysis in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides-tolerant Rubus 7 glaucus Benth. Juliana Arias1, Juan C. Rincón1*, Ana M. López1, and Marta L. Marulanda1 1Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira, Grupo de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Biotecnología, Carrera 27 No. 10-02 Pereira, Risaralda, Colombia. *Corresponding author ([email protected]). Received: 9 April 2019; Accepted: 30 July 2019; doi:10.4067/S0718-58392019000400565 ABSTRACT Andean blackberry (Rubus glaucus Benth.) is an important crop of the Andean region affected by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. In Colombia, tolerant plant material has been detected, but it has not been completely characterized. The objective of this research was oriented to analyze de novo transcriptome assembly of R. glaucus, and the comparison of the assembly with different reference genomes to further complete differential expression analysis of R. glaucus tolerant to C. gloespoiorides attack. To achieve this, three groups were used: infected tolerant material, infected susceptible material, and a susceptible group without inoculation. The RNA-seq sequencing was achieved through Illumina Hi-seq 2000. De novo assembly (Trinity, CD-HIT, TopHat) and functional annotation of sequences were carried out, additionally, mapping with reference genomes belonging to Rosaceae families was conducted (Bowtie2, TopHat). Subsequently, the differential expression was quantified (Cuffdiff) and analyzed through EdgeR. Variant analysis was made using MISA and SAMtools. After editing and assembly, 43579 consensus sequences were obtained (N50 = 489 bp; GC = 44.6%), annotation detected 35824 and 35602 sequences in Nt (partially non-redundant nucleotide sequences) and Nr (non-redundant protein sequences) databases, respectively. The 85% of Nr sequences was linked to members of Rosaceae family, mainly strawberry (67.6%).