Dreaming of Olympia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethics and Sport in Europe Drugs, Extremism and Other Forms of Discrimination It Is Currently Facing

SPORTS POLICY AND PRACTICE SERIES Defending ethics in sport is vital in order to combat the problems of corruption, violence, Ethics and sport in Europe drugs, extremism and other forms of discrimination it is currently facing. Sport refl ects nothing more and nothing less than the societies in which it takes place. However, if sport is to continue to bring benefi ts for individuals and societies, it cannot afford to neglect its ethical values or ignore these scourges. The major role of the Council of Europe and the Enlarged Partial Agreement on Sport (EPAS) in addressing the new challenges to sports ethics was confi rmed by the 11th Council of Europe Conference of Ministers responsible for Sport, held in Athens on 11 and 12 December 2008. A political impetus was given on 16 June 2010 by the Committee of Ministers, with the adoption of an updated version of the Code of Sports Ethics (Recommendation CM/Rec(2010)9), emphasising the requisite co-ordination between governments and sports organisations. The EPAS prepared the ministerial conference and stepped up its work in an international conference organised with the University of Rennes, which was attended by political leaders, athletes, researchers and offi cials from the voluntary sector. The key experiences described in the conference and the thoughts that it prompted are described in this publication. All the writers share the concern that the end result should be practical action – particularly in terms of the setting of standards – that falls within the remit of the EPAS and promotes the Council of Europe’s core values. -

Les Chroniques Du Val De Bièvre N°99 Eté 2018

LES CHRONIQUES DU VAL DE BIÈVRE N°99 ETÉ 2018 ISSN-2258-7284 N°99 Chroniques du Val de Bièvre Histoire, Patrimoine, Mémoire Été 2018 LES CHRONIQUES DU VAL DE BIÈVRE N°99 ETÉ 2018 Sommaire du N° 99 destes pendant ces vingt-cinq années de publication. Couverture : La Bièvre à Gentilly 1865, par Deroy, En mars dernier, lors de notre repas des Isidore-Laurent, Musée du Domaine départemen- vingt-cinq ans des Ateliers du Val de tal de Sceaux, ©Photographie de B. Chain Bièvre, en présence de notre président P 2 Sommaire, éditorial par Marcel BREILLOT d’honneur Patrick SIMON, ici près de P 3 Le prix de vertu par Mireille HEBRARD Madame RAJCHMAN, maire-adjointe P 5 Jean Baptiste de Montyon d’Arcueil, j’ai remis, aux élus d’Arcueil et par Marie VALLETTA de Cachan présents le centième numéro p 7 Monthyon, en pays Meldois de notre revue par Mireille HEBRARD p 10 L’inconnue d’une famille illustre par Marcel BREILLOT p 14 L’incident de l’école des dominicains d’Arcueil par Annie THAURONT p 17 La Dame Blanche par Alain BRUNOT p 21 Louise Michel par Marcel FREMONT p. 24 Ours, Publicités Chaque article, (textes et images), est pu- blié sous la seule responsabilité de son au- teur. Éditorial Vingt-cinq ans déjà, les Ateliers du Val de Bièvre ont-ils atteint l’âge de raison ? Dans ce numéro, nos chroniqueuses Mi- reille et Marie ont décidé de nous parler de vertu plutôt que de raison. Ce prix de vertu était décerné par l’Académie française. -

Supplement 25.07.2021

BLACK AND WHITE This week our Supplement is printed in the “Dominican” colours of black and white. Why these colours? They are the colours of the Dominican habit – but why so? THE WHITE At Baptism, each of is us clothed in a white garment. “You have become a new creation,” the priest says, “and have clothed yourself in Christ. See in this white garment the outward sign of your Christian dignity…” White is then the basic colour for all liturgical ministries: for the acolytes, for example, and although the priest and deacon wear coloured vestments on top, the white garment or “alb” underneath is always put on first. Before founding the Order, Dominic was a canon of Osma cathedral. Canons spent a great deal of time in church at prayer – perhaps even more than many monks – and so wore white. When Dominic founded his Order, it was natural enough that they adopted the white of their founder, who had until then been a canon. In fact, at first they wore a white surplice, too, though that was soon changed to the scapular, possibly under Cistercian influence, as Dominic was impressed by the monks of Citeaux and took many of the Order’s customs from them. THE BLACK If the white recalls our Baptism and the strong liturgical dimension of Dominican life, the black seems to have had a more prosaic origin. Europe can be cold in Winter, and the friars had to be out on the road, preaching. They needed a thick woollen cloak – and the cheapest wool to be had was black, unbleached wool. -

Can the Olympic Flame Kindle the Fire of Christianity? WOLFGANG VONDEY

Word & World Volume 23, Number 3 Summer 2003 Christian Enthusiasm: Can the Olympic Flame Kindle the Fire of Christianity? WOLFGANG VONDEY an into flame the gift of God!” sounds Paul’s appeal in 2 Tim 1:6. This advice “ has a particularly urgent ring in times when the flame of Christian enthusi- asm seems to have lost much of its fervor, and many Christians look at the un- quenched enthusiasm of the world for an example worth following. Fascination and enthusiasm are readily associated with many things in the world; some have even claimed that essentially all of existence can become an object of human fas- cination.1 Nonetheless, many find it extremely difficult to be fascinated by Chris- tian theology and ministry. At various times throughout history, individuals and groups have tried to revive a genuine Christian fascination, but with it have earned rather unflattering descriptions of being “sensual,” “ecstatic,” “aggressive,” “fa- natic,” or even “satanic.”2 Even so, voices have increased that call for more enthusi- asm and fascination in Christian theology and ministry. 1Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961) 63; Heribert Mühlen, Ent- sakralisierung (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 1971) 20-65, 130. 2See, e.g., Horace S. Ward, “The Anti-Pentecostal Argument,” in Aspects of Pentecostal-Charismatic Origins, ed. Vinson Synan (Plainfield, NJ: Logos International, 1975) 99-122. As the epitome of sport, the Olympic Games model a kind of “religious” enthusi- asm that has massive and magic appeal. Closer examination, however, reveals overwhelming difference between the enthusiasm of the Olympiad and the en- thusiasm of the Spirit—a difference that is essential to the Christian gospel. -

Le Corps Et Le Sport Acé M Atrick P

Le magazine du doyenné des Crêtes 14 N° de décembre 2012 crêtes Paroisses Saint-François d’Assise, Sainte-Claire, Saint-Sylve et Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Le corps et Le sport acé M atrick P Dossier Dieu est venu parmi nous Le corps pour quoi faire? ien des fois m’a été demandé pourquoi avec son esprit bien sûr, mais aussi son corps. Un p. 2 à 5 l’Église intervient lorsque des sujets tou- corps semblable au nôtre, un corps qui grandit et Bchent particulièrement le corps. Certains qui se transforme ; le bébé de la crèche sera l’en- même se demandent pourquoi l’Église attache fant que Marie et Joseph perdent en rentrant de un tel respect au corps de l’homme, puisqu’elle Jérusalem, sera l’homme que suivent les apôtres devrait s’intéresser spécialement à l’âme, lieu sur les routes de Galilée, sera l’homme défiguré tout particulier du spirituel. Vous ne le devinez dans la souffrance sur la croix, mais qui, au troi- • Lire, voir, écouter p. 6 pas, pourquoi ? sième jour, ressuscite. Alors, je vous donne rendez-vous le 25 dé- Et en ressuscitant, il nous indique que chacun cembre, ce jour où nous fêterons Noël. de nous est appelé à ressusciter. Oui, notre corps • Célébration de Noël p. 7 Bien sûr, autour de Noël, il y a tout le rituel des a de l’importance, oui notre corps est aimé de cadeaux, des repas de famille, de la fête mais il Dieu. y a plus que cela. Il y a la célébration que Dieu Je profite de cet éditorial pour souhaiter à cha- • L’Église et la représentation nous aime tant qu’Il est venu au milieu de nous cun bon et joyeux Noël et pour vous tous une et pas de n’importe quelle manière mais en de- bonne et joyeuse année 2013. -

Olympism and the Olympic Movement Olympism And

OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC WHAT IS OLYMPISM? THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT: ACTIVITIES OUTSIDE A philosophy of life. HOW DOES IT WORK? THE GAMES An ideal: the combination The structure of the Olympic Actions on various fronts MOVEMENT of sport, culture and education. Movement: the International 365 days a year: Sport for All, Olympic Committee (IOC), development through sport; Olympic values. the National Olympic Committees equal opportunities; education Olympic symbol and other (NOCs), the International and culture; sport for peace, identifying elements. Sports Federations (IFs) the environment and sustainable and the Organising Committees development; protecting for the Olympic Games (OCOGs). the health of athletes; combating illegal sports betting. 3 7 11 HISTORICAL MILESTONES Creation of the IOC in 1894 in Paris (France), on the initiative of Pierre de Coubertin. The eight presidents over a century. The IOC headquarters, This is a PDF interactive file. The headings of each page contain hyperlinks, in Lausanne (Switzerland) which allow to move from chapter to chapter. since 1915. Click on this icon to download the image. Cover: OG London 2012, Opening Ceremony – Entry of the Olympic flag into the stadium. © 2012 / International Olympic Committee (IOC) / JUILLIART, Richard 15 OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT WHAT IS OLYMPISM? 3 1. OG London 2012. Athletics, 5000m Men – Qualifications. WHAT IS OLYMPISM? Mohamed FARAH (GBR) 1st congratulates René Herrera (PHI) Olympism is a philosophy of life which places sport at the service at the end of the race. of humanity. This philosophy is based on the interaction of the qualities © 2012 / International Olympic Committee (IOC) / FURLONG, of the body, will and mind. -

OLYMPISM and the OLYMPIC MOVEMENT OLYMPISM and the OLYMPIC WHAT IS OLYMPISM? the OLYMPIC MOVEMENT: ACTIVITIES OUTSIDE a Philosophy of Life

OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC WHAT IS OLYMPISM? THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT: ACTIVITIES OUTSIDE A philosophy of life. HOW DOES IT WORK? THE GAMES MOVEMENT An ideal: the combination The structure of the Olympic Actions on various fronts of sport, culture and education. Movement: the International 365 days a year: Sport for All, Olympic Committee (IOC), development through sport; Olympic values. the National Olympic Committees equal opportunities; education Olympic symbol and other (NOCs), the International and culture; sport for peace, identifying elements. Sports Federations (IFs) the environment and sustainable and the Organising Committees development; protecting for the Olympic Games (OCOGs). the health of athletes; combating illegal sports betting. 3 7 11 HISTORICAL MILESTONES Creation of the IOC in 1894 in Paris (France), on the initiative of Pierre de Coubertin. The eight presidents over a century. The IOC headquarters, This is a PDF interactive fle. The headings of each page contain hyperlinks, which allow to move from chapter to chapter. in Lausanne (Switzerland) since 1915. Click on this icon to download the image. Cover: OG London 2012, Opening Ceremony – Entry of the Olympic fag into the stadium. © 2012 / International Olympic Committee (IOC) / JUILLIART, Richard 15 OLYMPISM AND THE OLYMPIC MOVEMENT WHAT IS OLYMPISM? 3 1. OG London 2012. Athletics, 5000m Men – Qualifcations. WHAT IS OLYMPISM? Mohamed FARAH (GBR) 1st congratulates René Herrera (PHI) Olympism is a philosophy of life which places sport at the service at the end of the race. © 2012 / International Olympic of humanity. This philosophy is based on the interaction of the qualities Committee (IOC) / FURLONG, of the body, will and mind. -

The Dominicans by Benedict M. Ashley, O. P. Contents Foreword 1

The Dominicans by Benedict M. Ashley, O. P. Contents Foreword 6. Debaters (1600s) 1. Founder's Spirit 7. Survivors (1700s) 2. Professor's (1200s) 8. Compromise (1800s) 3. Mystics (1300s) 9. Ecumenists (1900s) 4. Humanists (1400s) 10. The Future 5. Reformers (1500s) Bibliography Download a self-extracting, zipped, text version of the book, in MSWord .doc files, by clicking on this filename: ashdom.exe. Save to your computer and extract by clicking on the filename. Foreword In our pluralistic age we recognize many traditions have special gifts to make to a rich, well-balanced spirituality for our time. My own life has shown me the spiritual tradition stemming from St. Dominic, like that from his contemporary St. Francis, provides ever fresh insights. No tradition, however, can be understood merely by looking at its origins. We must see it unfold historically in those who have been formed by that tradition in many times and situations and have furthered its development. To know its essential strength, we need to see it tested, undergoing deformations yet recovering and growing. Therefore, I have tried to survey its eight centuries to give some sense of its chronology and its individual personalities, and of the inclusive Dominican Family. I have aimed only to provide a sketch to encourage readers to use the bibliography to explore further, but with regret I have omitted all documentation except to indicate the source of quotations. Translated 1 quotations are mine. I thank Sister Susan Noffke, O.P., Fr. Thomas Donlan, O.P., for encouraging this project and my Provincial, Fr. -

Conscience and Liberty Worldwide Human Rights & Religious Liberty Special Edition ______Dr

AGENTS AND AMBASSADORS FOR PEACE H O N O R I N G THE DIPLOMATS WORKING FOR PEACE WORLDWIDE !e United Nations, the Secretary General Ban KI-moon !e Council of Europe, the European Union, the O.S.C.E and the other international organizations’ efforts for respect and protection of human rights, rule of law, democracy and security… !e Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, Heiner BIELEFELDT THANKS TO !e governments and the parliaments, the civil society and the non-governmental organizations, the religions, beliefs and the representatives of academia and the media that have been focused on or are involved in the advocacy for peace, social justice and non-discrimination, education and protecting human rights, the respect for diversity and tolerance, and the defense of the principle of religious liberty and conscience for all people HONORING !e presidents of the Honorary Committee of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty (IADRL): Mrs. Franklin ROOSEVELT, Dr. Albert SCHWEITZER, Paul Henry SPAAK, Rene CASSIN, Edgar FAURE, Leopold Sedar SENGHOR, Mary ROBINSON !e former secretaries general of IADRL: Dr. Jean NUSSBAUM, Dr. Pierre LANARES, Dr. Gianfranco ROSSI, Dr. Maurice VERFAILLIE and Mr. Karel NOWAK THANKS FOR !e work of the former and current public affairs and religious liberty’s actors, colleagues, friends or board members: Dora, Laura, Robert, George, Mikulas, Herbert, Petru, Dietrich, Harald, Friedbert, Bert, Oliver, Paulo-Sergio, Kabrt, Valeriu, Tzanko, Ganoune, Pedro, Jean-Paul, Viorel, Alberto, Ioan, Tiziano, Nelu, Davide, Jose-Miguel, Jose, Antonio-Eduard, Cole, Sofia, Joaquin, Susan, Rafael, Rik, Silvio and board members: Gabriel Maurer, Jesus Calvo, Corrado Cozzi, David Jennah …and many other defenders and lobbyists SPECIAL THANKS TO !e former editorial assistants: Mari-Ange BOUVIER, Sigrid BUSCH, Christiane VERTALLIER !e president of the International Association for the Defense of Religious Liberty, Dr. -

Four Sports to Debut in Tokyo Olympics

BENNETT, COLEMAN & CO. LTD. | ESTABLISHED 1838 | TIMESOFINDIA.COM | NEW DELHI STUDENT EDITION ❖ How it all ❖ The brightest ❖ The biggest TODAY’S began in stars in the Indian feats in the history FRIDAY, JULY 23, 2021 Newspaper in ancient Greece contingent of Olympics Education EDITION TOKYO OLYMPICS PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 4 SPECIAL CLICK HERE: PAGE 1 AND 2 EDITION Traditions and values set over 12 centuries have kept the Olympic flame burning bright, reflecting on the true spirit of the Games - together, even in adversity. Even as Tokyo gears up for the big ceremony today, TIMES NIE digs into torch relay.The flame is carried to the host city to light the Olympic cauldron. The flame FASTER, HIGHER, was first used in modern times at the 1928 the past to see how the Games have withstood the test of Games at Amsterdam. The torch is usual- STRONGER - TOGETHER ly carried by runners. But over time, it has travelled on a boat, canoe, camels and air- This year, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) time to represent power, resilience and unity craft. In 2000, an underwater flare was tak- amended its ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’ motto to include en across the Great Barrier Reef to Sydney. the word ‘Together’, highlighting the need for solidari- ty during difficult times such as the Covid-19 pandemic. It is a move to adapt the motto to our times. The origi- EMBLEM nal motto, the Latin ‘Citius, Altius, Fortius’, was adopt- ed by the founder of the modern Games, Pierre De Cou- Ichimatsu moyo, a traditional Japanese che- bertin, in the 19th century,having borrowed it from his quered pattern, is the emblem of the Tokyo friend Henri Didon, a Dominican priest, who taught Games. -

Necrology O.M.I

NECROLOGY O.M.I. 2019.11.01 - Per diem Curia Generalizia Via Aurelia 290 00165 Roma ITALIA Back to our main database page 1 January Name place of death year of death Sc. Urbanus Vacher Aix 1853 Fr. Nicolaus Crane Sandhurst 1903 Fr. Michael Weber Le Bestin 1912 Fr. Paulus Bonnet Marseille 1919 Fr. Rodulfus Desmarais Hull 1929 Fr. Antonius Nordmann Gelsenkirchen 1935 Fr. Gulielmus Stanton Blenheim 1937 Fr. Gustavus Simonin Hobbema 1941 Fr. Cyprianus Bâtie St-Albert 1949 Fr. Georgius Kalb Usakos 1957 Fr. Ludovicus R. Lafleur Amos 1973 Fr. Kazimierz Czajka Morteaux 1984 Bro. Rémi Lyonnais Cap-de-la-Madeleine 1985 Fr. Paul Dufour Ottawa 1987 Fr. Julien Wijnants Ingolstadt 1992 Fr. Ettore Campagnano Albano 1994 Fr. Raymond Groulx Richelieu 1996 Fr. Bernard Hoffman Marseille 1999 Fr. Joseph Deehan Dublin 2001 Bro. René Darroux Lyon 2010 Fr. Louis Van den Eynde Geel 2014 Fr. Domenico Vitantonio Pescara 2015 Fr. François Buteau Richelieu 2019 2 January Name place of death year of death Fr. Ludovicus Belner Montréal 1879 Fr. Jacobus Walsh Lac Okanagan 1897 Fr. Julius Faugle Paris 1904 Fr. Franciscus Palm Macklin 1929 Bro. Joannes-Maria Pouliquen Le Pas 1936 Fr. Joannes A. Coumet Lyon 1940 Bro. Carolus Gaudel Pontmain 1941 necrology.cfm.html[27-Oct-19 8:26:47 AM] Fr. Jacobus J. Kenny Limerick 1959 Bro. Antonius Lintemeir Windhoek 1962 Fr. Joannes Straka Goyau 1970 Bro. Hugo Dwan Belmont 1971 Fr. Antonius B. McLean Belleville 1973 Fr. Augustinus Bastian Koblenz 1975 Fr. Dominique Noye Maroua 1983 Fr. Pierre Le Cossec Pontmain 1985 Fr. Clément Frappier Maillardville 1986 Bro. -

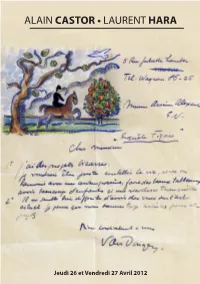

Alain Castor • Laurent Hara

ALAIN CASTOR • LAURENT HARA Jeudi 26 et Vendredi 27 Avril 2012 VentePub2627042012.indd 1 02/04/12 20:54 n° 221 (Antoine de Saint Exupéry) En Couverture - Kees Van DONGEN (lot n° 228) : lettre manuscrite adressée à Monsieur Arsène Alexandre (1859 - 1937), célèbre critique d’art français, auteur de nombreux ouvrages et articles sur l’art (Rodin, Gauguin, Barye, Daumier, etc...). Fondateur du journal satirique « Le Rire » et grand témoin de la vie mondaine à Paris à son époque. Madame Marie-Hélène GRINFENDER a eu la gentillesse de nous authentifier l’aquarelle originale de Van DONGEN. 9-10-11 MAI 2012 : EXCEPTIONNELLE COLLECTION D’AFFICHES HISTORIQUES : Ventes en préparation : importante bibliothèque : - livres d’art et catalogues raisonnés - albums périodiques Art et décoration (1897 à 1904) - beaux illustrés modernes : Le Conte de Lisle, le roman de Renard illustré par Jouve, Jean Genet, Beaudelaire, Rimbaud, Ronsard, Picasso, Dubuffet, De Staël, Mazeran, Schmied, Steinlen... - thèmes : ballets Russes, musique, photographies et divers - auteurs : Léonor de ROSENTHAL, Scaron, La Fontaine... - illustrateurs : Berthomé Saint André, Gustave Doré... Collection de gravures & dessins : cartes géographiques, plans, vues d’optiques, portraits, imageries, brevets, dessins. Pieter Van Den KEERE Plan de Paris 1617 - plan en élévation 4 planches, gravé à l’eau-forte et au burin. H 410 x L 2120 mm - H 410 x L 530 mm chaque planche VentePub2627042012.indd 2 02/04/12 20:54 ALAIN CASTOR • LAURENT HARA COMMISSAIRES-PRISEURS HABILITÉS - SVV N° AGRÉMENT 2009-690