Formative Assessment in the Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade by Grade Fine Arts Content Standards

Montgomery County Public Schools Pre-k–12 Visual Art Curriculum Framework Standard I: Students will demonstrate the ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to ideas, experiences, and the environment through visual art. Indicator 1: Identify and describe observed form By the end of the following grades, students will know and be able to do everything in the previous grade and the following content: Pre-K Kindergarten Grade 1 Grade 2 I.1.PK.a. I.1.K.a. I.1.1.a. I.1.2.a. Identify colors, lines, shapes, and Describe colors, lines, shapes, and Describe colors, lines, shapes, textures, Describe colors, lines, shapes, textures, textures that are found in the textures found in the environment. and forms found in observed objects forms, and space found in observed environment. and the environment. objects and the environment. I.1.K.b. I.1.1.b. I.1.2.b. I.1.PK.b. Represent observed form by combining Represent observed physical qualities Represent observed physical qualities Use colors, lines, shapes, and textures colors, lines, shapes, and textures. of people, animals, and objects in the of people, animals, and objects in the to communicate observed form. environment using color, line, shape, environment using color, line, shape, texture, and form. texture, form, and space. Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Clarifying Example: Given examples of lines, the student Take a walk around the school property. The student describes colors, lines, Given examples of assemblage, the identifies lines found in the trunk and Find and describe colors, lines, shapes, shapes, textures, and forms observed in a student describes colors, lines, shapes, branches of a tree. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Visual Arts Curriculum

August 2013 Ceramics I: Academic Grade Level 9, 10, 11, 12 Course Number 702 Subject Area Visual Arts Course Description This course introduces clay activities involving basic hand-building techniques, such as coil method, slab method, hollowing out and pinch method. Glazing techniques will be taught as well as techniques of clay preparation, storing of unfinished clay pieces and firing. Electric wheel throwing will be demonstrated. The final project will be of the students’ choosing and will involve a written description of the project to be accompanied with a research paper and presentation. Content Standards What aspects of the state standards does the course address? Standard 1. Students will demonstrate knowledge of the methods, materials, and techniques unique to visual arts. Standard 2. Students will demonstrate knowledge of the elements and principals design. Standard 3. Students will demonstrate their powers of observation, abstraction, invention, and expression in a variety of media, materials and techniques. Standard 4. Students will demonstrate knowledge of the processes of creating and exhibiting their own art work: drafts; critique; self -assessment; refinement; and exhibit preparation. Standard 5. Students will describe and analyze their own work and the work of others using appropriate visual arts vocabulary. When appropriate, students will connect their analysis to interpretation and evaluation. Standard 6. Students will describe the purposes for which works of dance, music, theater, visual arts, and architecture are created, and, when appropriate, interpret their meanings. Standard 7. Students will describe the roles of artists, patrons, cultural organizations, and art institutions in societies of the past and present. Standard 8. -

Project Update & Public Art Proposal

To: Center City Development Corporation (CCDC) Board of Directors From: DMC Staff, Planning & Development Department Date: June 10, 2015 RE: South End Underpass Improvements: Project Update & Public Art Proposal ________________________________________________________________________ Background: In 2014, DMC staff and the Henry Turley Company presented a joint proposal to the CCDC to make improvements at two (2) railroad underpasses in the South End neighborhood. The underpasses along Florida Street and South Main Street are dark, dirty, unpleasant, and discourage walking and biking in the area. At its March 16, 2014 meeting, the CCDC approved the South End Underpass Improvement Project. Staff’s original request included $125,000 for the total project, with approximately $50,000 of the budget dedicated to public art. Ultimately, the Board authorized up to $80,000 for Phase I of the project and instructed staff to bring back a detailed plan and budget for public art at a future meeting. The scope of work in Phase I includes cleaning the concrete surfaces, removing the unused roadbed at Florida Street, adding lighting above the sidewalk at two (2) underpasses, and the fees associated with traffic control, contracting, and design. Included in the $80,000 is up to $5,000 to design and plan the public art. The Henry Turley Company agreed to provide development services as an in-kind contribution to the overall project. These services include analysis of existing conditions, project scoping and design, project management, outreach to relevant agencies, and securing any required approvals. Current Status of Project: Over the past year, the Henry Turley Company has been actively securing the required approvals while working to keep the project within budget. -

The Functional Print Within the Print Market of the Late Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Century in Northern Europe and Italy

THE FUNCTIONAL PRINT WITHIN THE PRINT MARKET OF THE LATE FIFTEENTH AND EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY IN NORTHERN EUROPE AND ITALY Lyndsay Bennion A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2006 Committee: Dr. Allison Terry, Advisor Dr. Andrew Hershberger © 2006 Lyndsay Bennion All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Allison Terry, Advisor The focus of my thesis is the print market of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century. This market was a byproduct of the trade-based economy of Venice and cities in Northern Europe. The multiplicity of prints allowed for their widespread circulation among these cities. Religious prints were the first type of print to be disseminated via the various trade routes. Such prints experienced an immense popularity due to the devotional climate of early Renaissance society. Most often, they were utilized by consumers as devotional tools. Yet as the print market grew, so too did the tastes of consumers. A new type emerged who viewed the print as an art object and used it accordingly; collecting it and storing it away within their private print cabinets. It is these two different functions of the print that I am most interested in exploring. My intent is to view the print as a functional object whose use changed depending on the type of consumer who purchased it. The differing functions of the print resulted in a segmentation of the market into a larger devotional market and a much smaller fine print market. -

Visual Art Syllabus Dolan Middle School

Mr. DiGiovanna’s Visual Art Syllabus Dolan Middle School [email protected] _________________________________________________________________________________________________ 6th through 8th Grade Visual Art 6th and 7th Grade Students will spend the semester completing art projects designed to develop the student’s individual ideas and talents as an artist. The students will explore concepts that will increase their knowledge about art materials and use, art equipment, art history, and the application of it. 8th Grade Students will further explore the many venues of art education. Students will focus on higher order thinking skills while concentrating on specific applications of the given media. Students will use their skills in various relevant and rigorous projects. Scope and Sequence: The Visual Art curriculum is divided into the 6 major aspects of art creation. These will serve as a solid foundation for High School art and beyond. Projects that cover each of these aspects will be divided equally over the course of the semester. 1) Drawing: This is a foundational skill and is taught in many different ways throughout the semester. These may include pencil, charcoal, pastels, pen & ink, and colored pencil. 2) Painting: This area will explore two primary media techniques, watercolor and acrylic. 3) Sculpture: This area exposes students to the unique characteristics of creating in 3 dimensions and usually includes wire, plaster, and clay. 4) Printmaking: This area examines the creation process through the lens of producing repeated images. This is usually done through block and plate printing. 5) New Media: This area looks at contemporary design, illustration, and photography within the context of computer-based and digital media. -

Artist Citations

Downtown Fremont Public Art Program (Temporary Installation) – Metamorphosis Downloaded by Alina Kwak Thursday, December 15th 2016, 2:27pm Call ID: 990676 Artist ID: 7754 Status: Received Helle scharlingtodd Contact Partner Contact via Email [email protected] Phone Cell Web Site glassandmosaics.com Mailing Address . Custom Answers 2) Statement Regarding ThemeArtist must provide a written statement (up to 150 words) as part of their submittal explaining how their sculpture addresses and illustrates the theme. Art is like music, it stimulates the mind and the senses. With this in mind I build my pieces with emphasis on space, form, color, line, rhythm, and content. Artists are image makers and like the world's antennas, they feel, think and express reality. Momentarily I focus on "defining our spaces", like building a new society, using color, form and line as the building blocks. In addition to my public art projects I have developed a series of "color molecule" sculptures. The sculptures represent an homage to the smallest building block of life, the molecules. The theme is called "metamorphosis" which means change, and I see my work fitiing to the theme, as we all have metamorphed from molecules to a human being, so honoring the smallest entity in us seems allright. The work has semi circular motions, which gives a light feeling. The piece is 14' x 6;' x 6'. It is powder coated, the main color being turquise with colored glass inserted in the molecules. When the light shines through 3) Art Installation and De-Installation PlanPlease reference the attached site plan and provide an installation and de-installation plan and requirements for the attachment of the Artwork and the type of hardware to be used for the attachment. -

How Can the Public Art in Philadelphia Promote the Quality Of

How Can the Public Art in Philadelphia Promote the Quality of Public Users’ Life? The Public Perception Surveys in the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of Drexel University By Shu-Yi Kao (Drexel ID:10906183) In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of Master of Arts Administration Spring 2008 Table of Contents I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………3 II. Literature Review……………………………………………………………...5 III. The Development of Public Art in Philadelphia…………….……………….17 IV. Research Design and Methodology…………………………………………..27 V. Finding in the Surveys………………………………………………………..31 VI. Discussion and Summary…………………………………………………….51 List of References…………………………………………………………………….64 Appendix A—Survey Question Classification……………………………………….70 Appendix B—Survey Copy………………………………………………………….80 Appendix C—Survey Results………………………………………………………..86 Appendix D—Survey Pictures……………………………………...………………119 2 I. Introduction Problem Statement This research will examine the perception of public art by public users, including environmental, aesthetic, cultural, social and economic, and interpersonal impacts in the City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the past decades, public art has successfully received considerable attention. Initiated in 1967, the contemporary movement in public art rapidly spread out from the establishment of the Art in Public Places Program at the National Endowment for the Arts, which piloted various levels of governmental agencies to fund for the idea of public art support (Beardsley 1982; Lacy 1996). When the notable case of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc occurred in 1989 aroused vigorous debate about public art and its funding sources, it led people to rethink about the acceptance and the relationship of public art by the public. The more public art in public places is given a public use, the more involvement of government, communities, artists and public users is inevitable coordinated with multidisciplinary issues (Blair, Pijawka and Steiner 1998). -

Beauty and Perception 3

BEAUTY AND PERCEPTION 3 A visitor looks at artwork by artist Marchel Huisman during an art festival at the Dubai World Trade Center. ACADEMIC SKILLS THINK AND DISCUSS READING Using a concept map to identify supporting 1 What do you think makes certain things—for details example, landscapes, buildings, or images— WRITING Supporting a thesis beautiful? GRAMMAR Using restrictive and nonrestrictive adjective 2 What is the most beautiful thing you have ever clauses seen? Why is it beautiful? CRITICAL THINKING Applying ideas 47 NGL.Cengage.com/ELT Bringing the world to the classroom and the classroom to life A PART OF CENGAGE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED – NOT FOR RESALE EXPLORE THE THEME A Look at the information on these pages and answer the questions. 1. What is aesthetics? 2. According to the text, what factors affect aesthetic principles? 3. Is the image on the opposite page beautiful, in your opinion? If so, what makes it beautiful? B Match the correct form of the words in blue to their definitions. (n) the basic rules or laws of a particular theory (n) the size of something or its size in relation to other things (adj) relating to patterns and shapes with regular lines WHAT IS BEAUTY? Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy concerned with the study of beauty. Aesthetic principles provide a set of criteria for creating and evaluating artistic objects such as sculptures and paintings, as well as music, film, and other art forms. Aesthetic principles have existed almost as long as people have been producing art. Aesthetics were especially important to the ancient Greeks, whose principles have had a great influence on Western art. -

Public Art in Outdoor Space: How Environmental Art Can Influence Notions of Place

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2019 Public Art in Outdoor Space: How Environmental Art Can Influence Notions of Place Elsa Mark-Ng Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Repository Citation Mark-Ng, Elsa, "Public Art in Outdoor Space: How Environmental Art Can Influence Notions of Place" (2019). Honors Papers. 130. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Public Art in Outdoor Space: How Environmental Art Can Influence Notions of Place Elsa Mark-Ng 2018-2019 Oberlin College Environmental Studies Honors Research Main Advisor: Rumi Shammin Committee Members: Karl Offen Mark-Ng 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 2 Introduction 3 Literature Review and Site Visits 6 Public Art 6 Public Art Evaluation 27 Methods 32 Literature Review and Field Visits 32 Preparation for Art Installation 32 Creating the Art 34 The Installation 41 Collecting the Data 44 Analysis 45 Results 47 Survey Demographics 47 Descriptive Analysis 49 Qualitative Analysis 52 Statistical Analysis 54 Field Observation 57 Discussion 60 Conclusion 68 Acknowledgements 71 Works Cited 72 Appendix A 76 Appendix B 78 Appendix C 79 Mark-Ng 2 Executive Summary Public art has the potential to influence people’s sense of place and inspire environmental stewardship. By visiting existing public art, conducting a literature review, and creating a piece of public environmental art in an outdoor space in Oberlin, Ohio, I aim to learn how site-specific public art influences notions of place. -

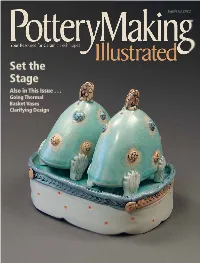

Set the Stage ➋ Eminently Repairable Anyone Can Fix an L&L Kiln with a Screwdriver and a Also in This Issue

Sept/Oct 2012 UPGRADE YOUR KILN ➊ Save Money L&L Kilns last years longer because the hard element holders protect the brick. Also we protect the electronic controls by keeping them away from the heat. Everything about the kiln is built with EXTRA materials and care. We don’t cost less but you get a lot more for your money. Set the Stage ➋ Eminently Repairable Anyone can fix an L&L Kiln with a screwdriver and a Also in This Issue . wrench. Our unique hard ceramic element holders make Going Thermal changing elements something Basket Vases even a novice can do. Clarifying Design Servicing an L&L control panel is a dream - it pulls down and stays perpendicular to the kiln - for easy viewing and working. ➌ Shop! 1) Google “L&L Kilns”! 2) Call toll free 877.468.5456 and ask for a recommended Distributor. 3) See hotkilns.com/distributors for a listing of Authorized L&L Distributors. L&L Kiln’s patented hard ceramic element holders protect your kiln. Toll Free: 877.468.5456 Swedesboro, NJ 08085 America’s Most Trusted Glazes™ Potter’s Choice Cone 5-6 3 New Glazes PC-57 Smokey Merlot PC-48 Art Deco Green PC-21 Arctic Blue amaco.com Look at what’s new!! The Bailey “Quick-Trim II” Bat The low cost Bailey QT2 (patent pending) is an exciting centering/trimming bat for tooling the feet on your pots. The Quick-Trim II has greater flexibility for trimming symmetrical, asymmetrical and multi-sided forms. It’s all done with (4) easily positioned holders with super holding power. -

2019 Cosmos Catalog.Indd

521 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10001 212 695 8035 / [email protected] onishigallery.com ASIA WEEK 2019 New York COVER IMAGE: ŌSUMI Yukie (1945-), Living National Treasure (2015) Silver Vase Zuiun (Auspicious Cloud), 2018; hammered silver with nunome zōgan (textile imprint inlay) decoration in lead and gold; h. 8 7/8 x w. 18 1/8 x d. 9 7/8 in. (22.5 x 46 x 25 cm) The Cosmos Within: Contemporary Japanese Metalwork and Ceramics In celebration of Asia Week New York 2019 and its 10-year anniversary as a leader of Japanese arts in the international art market of New York City, Onishi Gallery is proud to present a unique new exhibition to Western audiences: The Cosmos Within: Contemporary Japanese Metalwork and Ceramics. In this collection of contemporary Japanese kōgei arts (a class of artistic creations produced in close association with the needs and conditions of everyday life), Onishi Gallery demonstrates the vast cosmos and intimate nature that may be communicated through a delicate work of art. While European arts often express the wonders of the universe through dynamic artistry, Japanese kōgei artists use subtle techniques to represent the cosmos within—imagine the world that unfolds when one looks through the small lens of a kaleidoscope. Bringing numerous leading metalwork and ceramic artists from the Japanese contemporary art scene, Onishi Gallery works with both renowned and emerging talents to introduce their work to American audiences, connect them with museum collections, and enable American arts and cultural institutions to discover and partner with these international talents.