Practicing Pediatric Pathology Without a Microscope Raj P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRHG10-4 Text-Final.X

SCE Frequency Measurement Could Be Useful in the Prenatal Diagnosis of Roberts Syndrome Nenad Bukvic,1 Nicoletta Resta,2 Dragoslav Bukvic,3 Francesco C. Susca,1 Rosanna Bagnulo,2 Margherita Fanelli,4 and Ginevra Guanti2 1 Department of Internal and Public Medicine-Section of Medical Genetics, University of Bari, Bari, Italy 2 Department of Biomedicine of Evolutive Age-Section of Medical Genetics, University of Bari, Bari, Italy 3 Department of Gynaecology, General Hospital, Niksic, Montenegro 4 Department of Internal and Public Medicine-Section of Imaging Medicine, University of Bari, Bari, Italy n a previously published article (Resta et al., 2006) ‘repulsion’ of the peri- or para-centromeric regions Ion Robert’s syndrome in prenatal diagnosis, a (premature centromere separation [PCS]) together case of a 36-year-old woman and her 36-year-old, with splaying of the short arm of the acrocentrics and nonconsanguineous husband were presented. Our of the distal heterochromatic block of the long arm of findings suggest the existence of nonsense medi- the Y chromosome (German, 1979; Louie & German, ated decay (NMD) variability which could account 1981; Schüle et al., 2005). This cytogenetic phenome- for the varying severity reported in carriers of iden- non, called the RS effect, is observed in cells of tical mutations. Furthermore, fetal cells were used different tissues and appears to be more evident in to evaluate the influence of premature centromere chromosomes with large amounts of heterochromatin separation (PCS) on the sister chromatid exchange (Van den Berg & Francke, 1993). The first prenatal (SCE) and micronucleus (MN) frequency. Given the detection of the RS effect was reported by Willner et similar variation observed in the SCE frequencies, dependent on tissue/cell type (amniotic fluid al. -

TAR Syndrome, a Rare Case Report with Cleft Lip/Palate a Naseh, a Hafizi, F Malek, H Mozdarani, V Yassaee

The Internet Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatology ISPUB.COM Volume 14 Number 1 TAR Syndrome, a Rare Case Report with Cleft Lip/Palate A Naseh, A Hafizi, F Malek, H Mozdarani, V Yassaee Citation A Naseh, A Hafizi, F Malek, H Mozdarani, V Yassaee. TAR Syndrome, a Rare Case Report with Cleft Lip/Palate. The Internet Journal of Pediatrics and Neonatology. 2012 Volume 14 Number 1. Abstract TAR (Thrombocytopenia-Absent Radius) is a clinically –defined syndrome characterized by hypomegakarocytic thrombocytopenia and bilateral absence of radius in the presence of both thumbs. We describe a female neonate as a rare case of TAR syndrome with orofacial cleft. Bone marrow aspiration of the patient revealed a cellular marrow with marked reduction of megakaryocytes. Our clinical observation is consistent with TAR syndrome. However, other syndromes with cleft lip/palate and radial aplasia like Roberts syndrome (tetraphocomelia), Edwards syndrome and Fanconi and sc phocomelia (which has less degree of limb reduction) should be considered. Our cytogenetic study excludes other overlapping chromosomal syndromes. RBM8A analysis may reveal nucleotide alteration, leading to definite diagnosis. Our objective is adding this cleft lip and cleft palate to the literature regarding TAR syndrome. - Eva Klopocki, Harald Schulz, Gabriele Straub,Judith Hall,Fabienne Trotier, et al(February 2007) ;Complex inheritance pattern Resembeling Autosomal Recessive Inheritance Involving a Microdeletion in Thrombocytopenia-Absent Radius Syndrome.The American Journal of Human Genetics 80:232-240 INTRODUCTION syndrome. The hemorrhage happens during the first 14 TAR is a clinically-defined syndrome characterized by months of life. Hedberg and associates concluded in a study thrombocytopenia and bilateral radial bone aplasia in the that 18 of 20 deaths in 76 patients were due to hemorrhagic forearm with thumbs present. -

Soonerstart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions

SoonerStart Automatic Qualifying Syndromes and Conditions - Appendix O Abetalipoproteinemia Acanthocytosis (see Abetalipoproteinemia) Accutane, Fetal Effects of (see Fetal Retinoid Syndrome) Acidemia, 2-Oxoglutaric Acidemia, Glutaric I Acidemia, Isovaleric Acidemia, Methylmalonic Acidemia, Propionic Aciduria, 3-Methylglutaconic Type II Aciduria, Argininosuccinic Acoustic-Cervico-Oculo Syndrome (see Cervico-Oculo-Acoustic Syndrome) Acrocephalopolysyndactyly Type II Acrocephalosyndactyly Type I Acrodysostosis Acrofacial Dysostosis, Nager Type Adams-Oliver Syndrome (see Limb and Scalp Defects, Adams-Oliver Type) Adrenoleukodystrophy, Neonatal (see Cerebro-Hepato-Renal Syndrome) Aglossia Congenita (see Hypoglossia-Hypodactylia) Aicardi Syndrome AIDS Infection (see Fetal Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) Alaninuria (see Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Deficiency) Albers-Schonberg Disease (see Osteopetrosis, Malignant Recessive) Albinism, Ocular (includes Autosomal Recessive Type) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Brown Type (Type IV) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Negative (Type IA) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Tyrosinase Positive (Type II) Albinism, Oculocutaneous, Yellow Mutant (Type IB) Albinism-Black Locks-Deafness Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy (see Parathyroid Hormone Resistance) Alexander Disease Alopecia - Mental Retardation Alpers Disease Alpha 1,4 - Glucosidase Deficiency (see Glycogenosis, Type IIA) Alpha-L-Fucosidase Deficiency (see Fucosidosis) Alport Syndrome (see Nephritis-Deafness, Hereditary Type) Amaurosis (see Blindness) Amaurosis -

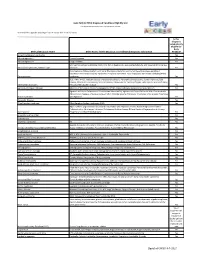

Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions List

Iowa Early ACCESS Diagnosed Conditions Eligibility List List adapted with permission from Early Intervention Colorado To search for a specific word type "Ctrl F" to use the "Find" function. Is this diagnosis automatically eligible for Early Medical Diagnosis Name Other Names for the Diagnosis and Additional Diagnosis Information ACCESS? 6q terminal deletion syndrome Yes Achondrogenesis I Parenti-Fraccaro Yes Achondrogenesis II Langer-Saldino Yes Schinzel Acrocallosal syndrome; ACLS; ACS; Hallux duplication, postaxial polydactyly, and absence of the corpus Acrocallosal syndrome, Schinzel Type callosum Yes Acrodysplasia; Arkless-Graham syndrome; Maroteaux-Malamut syndrome; Nasal hypoplasia-peripheral dysostosis-intellectual disability syndrome; Peripheral dysostosis-nasal hypoplasia-intellectual disability (PNM) Acrodysostosis syndrome Yes ALD; AMN; X-ALD; Addison disease and cerebral sclerosis; Adrenomyeloneuropathy; Siemerling-creutzfeldt disease; Bronze schilder disease; Schilder disease; Melanodermic Leukodystrophy; sudanophilic leukodystrophy; Adrenoleukodystrophy Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum Absence of the corpus callosum; Hypogenesis of the corpus callosum; Dysplastic corpus callosum Yes Agenesis of Corpus Callosum and Chorioretinal Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Chorioretinitis Abnormality; Agenesis of Corpus Callosum With Infantile Spasms And Ocular Anomalies; Chorioretinal Anomalies Aicardi syndrome with Agenesis Yes Alexander Disease Yes Allan Herndon syndrome Allan-Herndon-Dudley -

Miller-Dieker Syndrome

Miller-Dieker Syndrome In 1963, Miller reported two siblings with a specific pattern 3. Classification of lissencephaly (Dobyns et al., 1984) of malformations in which lissencephaly was a key feature. a. Type I Later in 1969, Dieker et al. described a similar condition. Jones i. Isolated lissencephaly sequence et al. in 1980 further characterized the phenotype and suggest- ii. Miller-Dieker syndrome ed the designation Miller-Dieker syndrome to distinguish it iii. Nonclassified forms from other lissencephaly syndromes. At present, Miller-Dieker b. Type II syndrome is known to be a contiguous gene disorder caused by i. Walker-Warburg syndrome haplo-insufficiency of a gene or genes having a major role in ii. Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy the development of the brain and the face. iii. Nonunclassified forms c. Rare forms GENETICS/BASIC DEFECTS i. Neu-Laxova syndrome 1. Genetics: a contiguous gene deletion syndrome involving ii. Cerebro-cerebellar syndrome chromosome 17p13.3 4. Cytogenetic mechanisms in Miller-Dieker syndrome a. Association of Miller-Dieker syndrome and del(17) (Dobyns et al., 1991) (p13) a. De novo abnormalities (44%) i. First reported by Dobyns et al. in 1983 i. Deletion (terminal or interstitial) (36%) ii. Familial cases reported by Miller (1963) with ii. Dicentric translocation (4%) affected members being carriers of an unbal- iii. Ring chromosome (4%) anced rearrangement from t(15;17)(q26.1;p13.3) b. Familial rearrangement (12%) iii. Family reported by Dieker et al. (1969) with i. Reciprocal translocation (8%) affected members being carriers of an unbal- ii. Pericentric inversions (4%) anced rearrangement from t(12;17) (q24.31; c. -

Medical Genetics and Genetic Counseling

Medical Genetics and Genetic Counseling Kelly Minks, MS, CGC Departments of Neurology and Medicine September 1, 2017 What is medical genetics? Any application of genetics to medical practice Study of inheritance of diseases in families Mapping of disease genes to specific locations on chromosomes Analysis of molecular mechanisms through which genes cause disease Diagnosis and treatment of disease Genetic counseling Why is medical genetics important to you? Genetic diseases make up a Genetic Approximate large percentage of the total condition prevalence disease burden in pediatric populations Down syndrome 1/700 to 1/1000 Increasing number of Cystic Fibrosis 1/2000 to 1/4000 pediatric deaths are due to (Caucasian) genetic disease in developing countries Fragile X syndrome 1/4000 males; Better understanding of 1/8000 females disease process Prevention Neurofibromatosis 1/3000 to 1/5000 Treatment type 1 Types of genetic diseases Chromosome disorders Single-gene disorders Multifactorial disorders Mitochondrial disorders Why is making an accurate diagnosis important? Allows for discussion of natural history, prognosis, management, treatment, earlier/more frequent disease screening, recurrence risk and prenatal diagnostic options, and referral to advocacy groups or clinical trials Involves recognition of phenotypic signs, dysmorphology exam, family history and testing Common indications for genetics referral Evaluation of individual with developmental delay or intellectual disability Individual with single or multiple malformations -

Medical Diagnosis/Conditions for Eligibility in AEIS

Medical Diagnosis/Conditions for Eligibility in AEIS 1) Achondroplasia 2) Agenesis of Corpus Callosum 3) Agyria (Lissencephaly) 4) Albinism 5) Amniotic Band syndrome 6) Anencephaly 7) Angelman’s syndrome 8) Anophthalmia 9) Apert syndrome 10) Aplasia of the brain (brain malformation/abnormality) 11) Arhinencephaly (Holoprosencephaly) 12) Arnold-Chiari syndrome 13) Arthrogryposis 14) Asperger syndrome/disorder 15) Asphyxiating Thoracic Dystrophy (Jeune syndrome) 16) Attachment disorder 17) Autism/Autism Spectrum disorder 18) Bardet-Biedl syndrome 19) Brain injury/degeneration 20) Brain malformation/abnormality 21) Cerebral Palsy (all types) 22) CHARGE syndrome 23) Chiari Malformation 24) Childhood Depression 25) Childhood Disintegrative disorder 26) Cornelia de Lange syndrome 27) Cortical vision impairment (vision loss/impairment) 28) Cri-du-Chat syndrome 29) Cytomegalovirus (CMV) 30) Dandy Walker syndrome/variant 31) De Morsier syndrome (Septo-Optic Dysplasia) 32) Developmental Apraxia 33) DiGeorge syndrome 34) Dilantin syndrome (Fetal Hydantoin syndrome) 35) Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21) 36) Edwards syndrome (Trisomy 18) 37) Encephalomalacia 38) Encephalopathy 39) Epilepsy (seizure disorder) 40) Fetal Alcohol syndrome 41) Fetal Hydantoin syndrome (Dilantin syndrome) 42) Fragile X syndrome 43) Genetic/Chromosomal malformation/abnormality (not listed) 44) Hearing Loss/Impairment 45) Heart Disease/Defect (not listed) 46) Hemiplegia 47) Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) 48) Holoprosencephaly (Arhinencephaly) 49) Holt Oram syndrome 50) Hydraencephaly -

87 Roberts Syndrome R

Roberts Syndrome 849 87 Roberts Syndrome RBS, Roberts-SC phocomelia syndrome, Differential Diagnosis pseudothalidomide syndrome • Thalidomide embryopathy • Baller-Gerold syndrome Tetraphocomelia, cleft lip/palate, ectrodactyly/malpo- • Trisomy 18 sition of thumbs, hypertelorism, exophthalmos • Lethal Nager acrofacial dysostosis • TAR syndrome Frequency: Rare (over 100 cases reported). • DK-phocomelia syndrome • Tetra-amelia with multiple malformations Genetics Autosomal recessive (OMIM 268300); the disease Radiographic Features locus maps to chromosome 8p21; premature cen- Limbs tromere separation; chromosome puffing of hetero- • Asymmetrical reduction anomalies of variable chromatic regions around the centromeres and degree in the long bones of all extremities (90%), nucleolar organizers. ranging from mild hypoplasia to complete aplasia of arms and legs with rudimentary digits; upper Clinical Features extremities usually more involved than lower • Severe growth retardation (pre-/postnatal) extremities, with humerus shorter than femur; • Microcephaly (80%), sparse hair radius usually shorter than ulna • Hypertelorism, prominent eyes, eyelids coloboma, • Humeroradial/humeroulnar synostosis, corneal opacity, cataracts femorotibial synostosis (10%) • Wide nasal bridge, hypoplastic nose, facial hem- • Radial deviation of hands angioma • Oligodactyly, asymmetrical shortening of fingers • Midfacial cleft (80%), usually bilateral cleft lip/ (80%), absent or hypoplastic phalanges (especial- palate, prominent premaxilla, delayed eruption of ly 1st -

Gen Genetic Test Genetic Test Subjectkey (NDAR GUID)

Gen_Genetic_Test Genetic Test Subjectkey (NDAR GUID) Source subject ID Age (in months) Genetic test Date of test Genetic test results Normal Abnormal Comments Test provider Genetic Test Subjectkey (NDAR GUID) Source subject ID Age (in months) Genetic test Date of test Genetic test results Normal Abnormal Comments Test provider Example of table for NDAR data submission: Subjectkey Src_subject_id Interview_age Interview_date Genetic_test Test_result Test_provider Genetic_test_notes NDAR_INVEW671NRA MT_R21_006 36 1/1/2008 ASD_NRXN1 Normal GeneDx none NDAR_INVEW671NRA MT_R21_006 36 1/1/2008 NF2_NF2 Abnormal GeneDx none Gen_Genetic_Test # Test Marker Chromosome Chromosome Condition Gene Name Location 1 Test1_1p32-p31 1p32-p31 1 1p32-p31 Chromosome 1p32-p31 deletion NFIA syndrome 2 Test2_SLC2A1 SLC2A1 1 1p34.2 GLUT1 deficiency syndrome type 1 GLUT1 and type 2 3 Test3_1p36 1p36 1 1p36 Chromosome 1p36 deletion syndrome 4 Test4_1q21.1 1q21.1 1 1q21.1 Chromosome 1q21.1 deletion syndrome 5 Test5_1q41q42 1q41q42 1 1q41-q42 1q41-q42 deletion syndrome DISP1, SUSD4, CAPN2, TP53BP2, FBXO28 6 Test6_2p16.1-p15 2p16.1-p15 2 2p16.1-p15 Chromosome 2p16.1-p15 deletion syndrome 7 Test7_NRXN1 NRXN1 2 2p16.3 Autism Spectrum Disorders NRXN1 8 Test8_SOS1 SOS1 2 2p22.1 Noonan syndrome 4 SOS1 9 Test9_2q13 2q13 2 2q13 Autism Spectrum Disorders 10 Test10_NPHP1 NPHP1 2 2q13 Joubert syndrome NPHP1 11 Test11_ZEB2 ZEB2 2 2q22 Mowat-Wilson syndrome ZEB2 12 Test12_MBD5 MBD5 2 2q23.1 Rett syndrome MBD5 13 Test13_SLC4A10 SLC4A10 2 2q23-q24 Autism Spectrum Disorders SLC4A10 -

Detailed Listing of Compassionate Allowance Cases

DETAILED LISTING OF COMPASSIONATE ALLOWANCE CASES ACUTE LEUKEMIA Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Acute Myeloid Leukemia Adrenal Carcinoma, Adrenocortical Carcinoma, Adrenocortical ADRENAL CANCER Cancer, Cancer of the Adrenal Cortex, Carcinoma of the Adrenal Cortex Lymphoma - non-Hodgkin's; Lymphocytic lymphoma; ADULT NON-HODGKIN Histiocytic lymphoma; Lymphoblastic lymphoma; Cancer - non- LYMPHOMA Hodgkin's lymphoma ADULT ONSET HUNTINGTON Huntington's chorea; Huntington's Disease DISEASE AGS; Cree Encephalitis; Encephalopathy with Basal Ganglia Calcification; Pseudo-TORCH Syndrome; AICARDI - GOUTIERES Pseudotoxoplasmosis Syndrome; Familial Infantile SYNDROME Encephalopathy with Intracranial Calcification and Chronic Cerebrospinal Fluid Lymphocytosis Alexander Syndrome, Dysmyelogenic Leukodystrophy, Dysmyelogenic Leukodystrophy-Megalobare, Fribrinoid ALEXANDER DISEASE (ALX) - Degeneration of Astrocytes-Infantile type, Fibrinoid NEONATAL AND INFANTILE Leukodystrophy-Infantile type, Hyaline Panneuropathy, Leukodystrophy with Rosenthal Fibers, Megalencephaly with Hyaline Inclusion, Megalencephaly with Hyaline Panneuropathy Allan-Herndon Syndrome; X-linked Intellectual Deficit with ALLAN-HERNDON-DUDLEY Hypotonia; Monocarboxylate Transporter 8 Deficiency; MCT8 SYNDROME Deficiency; MCT8 Specific Thyroid Hormone Cell Transporter Deficiency; MCT8 SLC16A2 Holoprosencephaly; HPE; Holoprosencephaly 1 Alobar; ALOBAR Familial Alobar Holoprosencephaly; Holoprosencephaly HOLOPROSENCEPHALY Sequence Alpers Syndrome; Alpers Progressive Infantile Poliodystrophy; -

Roberts Syndrome: Clinical and Cytogenetic Aspects

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.19.2.116 on 1 April 1982. Downloaded from Journal ofMedical Genetics, 1982, 19, 116-119 Roberts syndrome: clinical and cytogenetic aspects N P MANN, J FITZSIMMONS, E FITZSIMMONS, AND P COOKE From the Clinical Genetic Service, City Hospital, Nottingham NG5 JPB SUMMARY Roberts syndrome is reported in two sibs of consanguineous parents. Both infants had severe tetraphocomelia, facial clefting, and other serious malformations. In addition they were found to have an unusual cytogenetic abnormality with distortion of the normal sister chromatid relationship in many chromosomes. Roberts syndrome is a rare condition, originally Nottingham City Hospital on 9.1.79. She and her described in 1919 and reported in fewer than 30 husband were first cousins and the couple's mothers children since that time.1 There have been several were sisters. She had been in good health throughout comprehensive reviews of the published cases2 and the pregnancy but was consistently noted to have a recently Herrmann and Opitz3 compared Roberts fundal height below that expected for her dates. syndrome with another similar condition, the SC There was no history of drug ingestion other than phocomelia or pseudothalidomide syndrome. They oral iron and she had not taken clonidine at any concluded, at the time of their report, that there time.6 The infant's birthweight was 1 040 kg, and were insufficient grounds for suggesting that these although there were a few spontaneous gasps she were different entities although there are undoubted died 17 minutes after delivery. On examination differences in severity and life expectancy. -

Rock-A-Bye Baby

Rock-a-Bye Baby EI Services for the youngest, smallest and most vulnerable infants Children’s of Alabama Sheree York, PT,DPT,PCS Chantel Jno-Finn, PT, DPT Lauren Lovett, PT, DPT Christy Moran, OTR/L Special Guests Anna Ruth McCalley, MS,OTR/L, Mom & Frances Objectives • Recognize the eligible diagnoses for premature and medically complex infants • Recognize the risks associated with complex medical conditions • Select and complete appropriate evaluations of these infants • Provide family-centered EI services designed to support the families and promote the development and care of these infants AEIS Qualifying Medical Diagnoses/Conditions • Achondroplasia • Brain injury/degeneration • Agenesis of Corpus Callosum • Brain malformation/abnormality • Agyria (Lissencephaly syndrome (Miller-Dieker – Macroencephaly syndrome)) – Macrogyria • Albinism – Megalencephaly • Amniotic Band syndrome – Microcephaly • Anencephaly – Microgyria • Angelman’s syndrome • Cataracts • Anophthalmia • Cerebral Palsy (all types) • Apert syndrome • CHARGE syndrome • Aplasia of the brain (brain malformation/abnormality) • Chiari Malformation • Arnold-Chiari syndrome • Childhood Depression • Arthrogryposis • Childhood Disintegrative disorder • Asperger syndrome/disorder • Coloboma • Asphyxiating Thoracic Dystrophy (Jeune syndrome) • Cone Dystrophy • Attachment disorder • Connexin 26 • Auditory Neuropathy • Cornelia de Lange syndrome • Autism/Autism Spectrum disorder • Cortical vision impairment (vision loss/impairment) • Bardet-Biedl syndrome • Cri-du-Chat syndrome •