Maneuvering Clinical Pathways for Crohn's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BAFF-Neutralizing Interaction of Belimumab Related to Its Therapeutic Efficacy for Treating Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03620-2 OPEN BAFF-neutralizing interaction of belimumab related to its therapeutic efficacy for treating systemic lupus erythematosus Woori Shin1, Hyun Tae Lee1, Heejin Lim1, Sang Hyung Lee1, Ji Young Son1, Jee Un Lee1, Ki-Young Yoo1, Seong Eon Ryu2, Jaejun Rhie1, Ju Yeon Lee1 & Yong-Seok Heo1 1234567890():,; BAFF, a member of the TNF superfamily, has been recognized as a good target for auto- immune diseases. Belimumab, an anti-BAFF monoclonal antibody, was approved by the FDA for use in treating systemic lupus erythematosus. However, the molecular basis of BAFF neutralization by belimumab remains unclear. Here our crystal structure of the BAFF–belimumab Fab complex shows the precise epitope and the BAFF-neutralizing mechanism of belimumab, and demonstrates that the therapeutic activity of belimumab involves not only antagonizing the BAFF–receptor interaction, but also disrupting the for- mation of the more active BAFF 60-mer to favor the induction of the less active BAFF trimer through interaction with the flap region of BAFF. In addition, the belimumab HCDR3 loop mimics the DxL(V/L) motif of BAFF receptors, thereby binding to BAFF in a similar manner as endogenous BAFF receptors. Our data thus provides insights for the design of new drugs targeting BAFF for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. 1 Department of Chemistry, Konkuk University, 120 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05029, Republic of Korea. 2 Department of Bio Engineering, Hanyang University, 222 Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 04763, Republic of Korea. These authors contributed equally: Woori Shin, Hyun Tae Lee, Heejin Lim, Sang Hyung Lee. -

Xolair/Omalizumab

Therapeutic/Humanized Antibodies ELISA Kits ‘Humanized antibodies” are ‘Animal Antibodies’ that have been modified by recombinant DNA-technology to reduce the overall content of the animal- portion of immunoglobulin so as to increase acceptance by humans or minimize ‘rejection’. By analogy, if the hands of a mouse is actually responsible for grabbing things then ‘humanized-mouse’ will only contain the ‘mouse hands’ and the rest of the body will be human. Since the size of the IgGs is similar in mouse and human, the size of the native mouse IgG and the ‘humanized IgG’ does not significantly change. Antigen recognition property of an antibody actually resides in small portion of the IgG molecule called the ‘antigen binding site or Fab’. Therefore, humanized antibodies contain the minimal portion from the Fab or the epitopes necessary for antigen binding. The process of "humanization of antibodies" is usually applied to animal (mouse) derived monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic use in humans (for example, antibodies developed as anti-cancer drugs). Xolair (Anti-IgE) is an example of humanized IgG. The portion of the mouse IgG that remains in the ‘humanized IgG’ may be recognized as foreign by humans and may result into the generation of “Human Anti-Drug Antibodies (HADA). The presence of anti-Drug antibody (e.g., Human Anti-Rituximab IgG) that may limit the long-term usage the humanized antibody (Rituximab). Not all monoclonal antibodies designed for human therapeutic use need be humanized since many therapies are short-term. The International Nonproprietary Names of humanized antibodies end in “-zumab”, as in “omalizumab”. Humanized antibodies are distinct from chimeric or fusion antibodies. -

Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Biologic Medications

REVIEW CME MOC Selena R. Pasadyn, BA Daniel Knabel, MD Anthony P. Fernandez, MD, PhD Christine B. Warren, MD, MS Cleveland Clinic Lerner College Department of Pathology Co-Medical Director of Continuing Medical Education; Department of Dermatology, Cleveland Clinic; of Medicine of Case Western and Department of Dermatology, W.D. Steck Chair of Clinical Dermatology; Director of Clinical Assistant Professor, Cleveland Clinic Reserve University, Cleveland, OH Cleveland Clinic Medical and Inpatient Dermatology; Departments of Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Dermatology and Pathology, Cleveland Clinic; Assistant Reserve University, Cleveland, OH Clinical Professor, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH Cutaneous adverse effects of biologic medications ABSTRACT iologic therapy encompasses an expo- B nentially expanding arena of medicine. Biologic therapies have become widely used but often As the name implies, biologic therapies are de- cause cutaneous adverse effects. The authors discuss the rived from living organisms and consist largely cutaneous adverse effects of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) of proteins, sugars, and nucleic acids. A clas- alpha inhibitors, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) sic example of an early biologic medication is inhibitors, small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors insulin. These therapies have revolutionized (TKIs), and cell surface-targeted monoclonal antibodies, medicine and offer targeted therapy for an including how to manage these reactions -

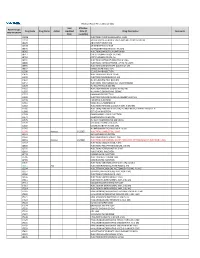

2021 Prior Authorization List Part B Appendix a (PDF)

Medicare Part B PA List Effective 2021 Last Effective Part B Drugs: Drug Code Drug Name Action Updated Date (if Drug Description Comments STEP THERAPY Date available) C9050 INJECTION, EMAPALUMAB-LZSG, 1 MG C9122 MOMETASONE FUROATE SINUS IMPLANT 10 MCG SINUVA J0129 ABATACEPT INJECTION J0178 AFLIBERCEPT INJECTION J0570 BUPRENORPHINE IMPLANT 74.2MG J0585 INJECTION,ONABOTULINUMTOXINA J0717 CERTOLIZUMAB PEGOL INJ 1MG J0718 CERTOLIZUMAB PEGOL INJ J0791 INJECTION CRIZANLIZUMAB-TMCA 5 MG J0800 INJECTION, CORTICOTROPIN, UP TO 40 UNITS J0896 INJECTION LUSPATERCEPT-AAMT 0.25 MG J0897 DENOSUMAB INJECTION J1300 ECULIZUMAB INJECTION J1428 INJECTION ETEPLIRSEN 10 MG J1429 INJECTION GOLODIRSEN 10 MG J1442 INJ FILGRASTIM EXCL BIOSIMIL J1447 INJECTION, TBO-FILGRASTIM, 1 MICROGRAM J1459 INJ IVIG PRIVIGEN 500 MG J1555 INJECTION IMMUNE GLOBULIN 100 MG J1556 INJ, IMM GLOB BIVIGAM, 500MG J1557 GAMMAPLEX INJECTION J1558 INJECTION IMMUNE GLOBULIN XEMBIFY 100 MG J1559 HIZENTRA INJECTION J1561 GAMUNEX-C/GAMMAKED J1562 INJECTION; IMMUNE GLOBULIN 10%, 5 GRAMS J1566 INJECTION, IMMUNE GLOBULIN, INTRAVENOUS, LYOPHILIZED (E.G. P J1568 OCTAGAM INJECTION J1569 GAMMAGARD LIQUID INJECTION J1572 FLEBOGAMMA INJECTION J1575 INJ IG/HYALURONIDASE 100 MG IG J1599 IVIG NON-LYOPHILIZED, NOS J1602 GOLIMUMAB FOR IV USE 1MG J1745 INJ INFLIXIMAB EXCL BIOSIMILR 10 MG J1930 Remove 1/1/2021 INJECTION, LANREOTIDE, 1 MG J2323 NATALIZUMAB INJECTION J2350 INJECTION OCRELIZUMAB 1 MG J2353 Remove 1/1/2021 INJECTION, OCTREOTIDE, DEPOT FORM FOR INTRAMUSCULAR INJECTION, 1 MG J2357 INJECTION, OMALIZUMAB, -

Cimzia (Certolizumab Pegol) AHM

Cimzia (Certolizumab Pegol) AHM Clinical Indications • Cimzia (Certolizumab Pegol) is considered medically necessary for adult members 18 years of age or older with moderately-to-severely active disease when ALL of the following conditions are met o Moderately-to-severely active Crohn's disease as manifested by 1 or more of the following . Diarrhea . Abdominal pain . Bleeding . Weight loss . Perianal disease . Internal fistulae . Intestinal obstruction . Megacolon . Extra-intestinal manifestations: arthritis or spondylitis o Crohn's disease has remained active despite treatment with 1 or more of the following . Corticosteroids . 6-mercaptopurine/azathioprine • Certollizumab pegol (see note) is considered medically necessary for persons with active psoriatic arthritis who meet criteria in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: Biological Therapies. • Cimzia, (Certolizumab Pegol), alone or in combination with methotrexate (MTX), is considered medically necessary for the treatment of adult members 18 years of age or older with moderately-to-severely active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). • Cimzia (Certolizumab pegol is considered medically necessary for reducing signs and symptoms of members with active ankylosing spondylitis who have an inadequate response to 2 or more NSAIDs. • Cimzia (Certolizumab Pegol) is considered investigational for all other indications (e.g.,ocular inflammation/uveitis; not an all-inclusive list) because its effectiveness for indications other than the ones listed above has not been established. Notes • There are several brands of targeted immune modulators on the market. There is a lack of reliable evidence that any one brand of targeted immune modulator is superior to other brands for medically necessary indications. Enbrel (etanercept), Humira (adalimumab), Remicade (infliximab), Simponi (golimumab), Simponi Aria (golimumab intravneous), and Stelara (ustekinumab) brands of targeted immune modulators ("least cost brands of targeted immune modulators") are less costly to the plan. -

Anti-TNF-Α (Certolizumab), Humanized Antibody

FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY! rev 06/21 Anti-TNF-α (Certolizumab), Humanized Antibody CATALOG NO.: A2142-100 (100 µg) BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION: The research-grade biosimilar is a humanized TNF-α monoclonal antibody. The original monoclonal antibody (Certolizumab pegol (CZP)) consists of polyethylene glycol conjugated to the antigen-binding fragment of the humanized monoclonal antibody. The antibody targets and neutralizes soluble and membrane forms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and inhibits TNF-α mediated signaling in vitro. Unlike other TNF inhibitors, this antibody does not contain the Fc region. As a result, decreased Fc-mediated effects such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) are observed. The original monoclonal antibody received FDA approval to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis. TNFSF2, TNF-alpha, TNFA, TNF-α, TNFα ALTERNATE NAMES: ANTIBODY TYPE: Monoclonal HOST/ISOTYPE: Recombinant / Fab-IgG1-kappa SOURCE: CHO cells IMMUNOGEN: Human TNF-α FORM: Liquid FORMULATION: In PBS, pH 7.5 SPECIES REACTIVITY: Human STORAGE CONDITIONS: Store at -80 ºC. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles This information is only intended as a guide. The optimal dilutions must be determined by the user RELATED PRODUCTS: Anti-TNF-α (Adalimumab), humanized Antibody (Cat. No. A1048) Anti-TNF alpha (Infliximab), Human IgG1 Antibody (Cat. No. A1097) Anti-TNF alpha (Humicade), Human IgG4 Antibody (Cat. No. A1093) Anti-EGFR (Cetuximab), Chimeric Antibody (Cat. No. A1047) Anti-EGFR (Matuzumab), Human IgG1 Antibody (Cat. No. A1090) FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY! Not to be used on humans. 155 S. Milpitas Blvd., Milpitas, CA 95035 USA | T: (408)493-1800 F: (408)493-1801 | www.biovision.com | [email protected] . -

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX 4: Search Strategies Syntax Guide For

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX 4: Search Strategies Pubmed, Embase Perioperative Management - PubMed Search Strategy – March 6, 2016 Syntax Guide for PubMed [MH] = Medical Subject Heading, also [TW] = Includes all words and numbers in known as MeSH the title, abstract, other abstract, MeSH terms, MeSH Subheadings, Publication Types, Substance Names, Personal Name as Subject, Corporate Author, Secondary Source, Comment/Correction Notes, and Other Terms - typically non-MeSH subject terms (keywords)…assigned by an organization other than NLM [SH] = a Medical Subject Heading [TIAB] = Includes words in the title and subheading, e.g. drug therapy abstracts [MH:NOEXP] = a command to retrieve the results of the Medical Subject Heading specified, but not narrower Medical Subject Heading terms Boolean Operators OR = retrieves results that include at least AND = retrieves results that include all the one of the search terms search terms NOT = excludes the retrieval of terms from the search Perioperative Management PubMed Search Strategy – March 6, 2016 Search Query #1 ((((ARTHROPLASTY, REPLACEMENT, HIP[MH] OR HIP PROSTHES*[TW] OR HIP REPLACEMENT*[TIAB] OR HIP ARTHROPLAST*[TIAB] OR HIP TOTAL REPLACEMENT*[TIAB] OR FEMORAL HEAD PROSTHES*[TIAB]) OR (ARTHROPLASTY, REPLACEMENT, KNEE[MH] OR KNEE PROSTHES*[TW] OR KNEE REPLACEMENT*[TW] OR KNEE ARTHROPLAST*[TW] OR KNEE TOTAL REPLACEMENT*[TIAB]) OR (ARTHROPLAST*[TW] AND (HIP[TIAB] OR HIPS[TIAB] OR KNEE*[TIAB])) AND (("1980/01/01"[PDAT] : "2016/03/06"[PDAT]) AND ENGLISH[LANG])) NOT (((("ADOLESCENT"[MESH]) OR "CHILD"[MESH]) -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0172932 A1 Peyman (43) Pub

US 20170172932A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2017/0172932 A1 Peyman (43) Pub. Date: Jun. 22, 2017 (54) EARLY CANCER DETECTION AND A 6LX 39/395 (2006.01) ENHANCED IMMUNOTHERAPY A61R 4I/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. (71) Applicant: Gholam A. Peyman, Sun City, AZ CPC .......... A61K 9/50 (2013.01); A61K 39/39558 (US) (2013.01); A61K 4I/0052 (2013.01); A61 K 48/00 (2013.01); A61K 35/17 (2013.01); A61 K (72) Inventor: sham A. Peyman, Sun City, AZ 35/15 (2013.01); A61K 2035/124 (2013.01) (21) Appl. No.: 15/143,981 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: May 2, 2016 A method of therapy for a tumor or other pathology by administering a combination of thermotherapy and immu Related U.S. Application Data notherapy optionally combined with gene delivery. The combination therapy beneficially treats the tumor and pre (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 14/976,321, vents tumor recurrence, either locally or at a different site, by filed on Dec. 21, 2015. boosting the patient’s immune response both at the time or original therapy and/or for later therapy. With respect to Publication Classification gene delivery, the inventive method may be used in cancer (51) Int. Cl. therapy, but is not limited to such use; it will be appreciated A 6LX 9/50 (2006.01) that the inventive method may be used for gene delivery in A6 IK 35/5 (2006.01) general. The controlled and precise application of thermal A6 IK 4.8/00 (2006.01) energy enhances gene transfer to any cell, whether the cell A 6LX 35/7 (2006.01) is a neoplastic cell, a pre-neoplastic cell, or a normal cell. -

POLICY Document for Cimzia

POLICY Document for Cimzia The overall objective of this policy is to support the appropriate and cost effective use of the medication, specific to use of preferred medication options, and overall clinically appropriate use. This document provides specific information to both sections of the overall policy. Section 1: Preferred Product • Policy information specific to preferred medications Section 2: Clinical Criteria • Policy information specific to the clinical appropriateness for the medication Section 1: Preferred Product EXCEPTIONS CRITERIA DISEASE-MODIFYING ANTIRHEUMATIC DRUGS PRODUCTS PREFERRED PRODUCTS: ENTYVIO, ILUMYA, REMICADE, SIMPONI ARIA, STELARA IV POLICY This policy informs prescribers of preferred products and provides an exception process for targeted products through prior authorization. I. PLAN DESIGN SUMMARY This program applies to the disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) products specified in this policy. Coverage for targeted products is provided based on clinical circumstances that would exclude the use of the preferred product and may be based on previous use of a product. The coverage review process will ascertain situations where a clinical exception can be made. For psoriasis, this program applies to all adult members requesting treatment with a targeted product. For all other indications, this program applies to adult members who are new to treatment with a targeted product for the first time. Each referral is reviewed based on all utilization management (UM) programs implemented for the client. Table. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for autoimmune conditions Products • Entyvio (vedolizumab) • Simponi Aria (golimumab, Preferred • Ilumya (tildrakizumab-asmn) intravenous) • Remicade (infliximab) • Stelara IV (ustekinumab)* • Actemra (tocilizumab) • Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb) Targeted • Avsola (infliximab-axxq) • Orencia (abatacept) • Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) • Renflexis (infliximab-abda) *Stelara IV is indicated for a one time induction dose for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. -

Active Conventional Treatment and Three Different Biological Treatments in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis

BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.m4328 on 2 December 2020. Downloaded from RESEARCH Active conventional treatment and three different biological treatments in early rheumatoid arthritis: phase IV investigator initiated, randomised, observer blinded clinical trial Merete Lund Hetland,1,2 Espen A Haavardsholm,3 Anna Rudin,4,5 Dan Nordström,6,7 Michael Nurmohamed,8,9 Bjorn Gudbjornsson,10,11 Jon Lampa,12 Kim Hørslev-Petersen,13,14 Till Uhlig,3,15 Gerdur Grondal,10,11 Mikkel Østergaard,1,2 Marte S Heiberg,3 Jos Twisk,16 Kristina Lend,12 Simon Krabbe,1,2 Lise Hejl Hyldstrup,1,2 Joakim Lindqvist,12 Anna-Karin Hultgård Ekwall,4,5 Kathrine Lederballe Grøn,1 Meliha Kapetanovic,17 Francesca Faustini,12 Riitta Tuompo,6,7 Tove Lorenzen,18 Giovanni Cagnotto,19,20 Eva Baecklund,21 Oliver Hendricks,13 Daisy Vedder,8 Tuulikki Sokka-Isler,22 Tomas Husmark,23 Maud-Kristine Aga Ljoså,24 Eli Brodin,25 Torkell Ellingsen,26 Annika Söderbergh,27 Milad Rizk,28 Åsa Reckner Olsson,29 Per Larsson,30 Line Uhrenholt,31 Søren Andreas Just,32 David John Stevens,33 Trine Bay Laurberg,34 Gunnstein Bakland,35 Inge C Olsen,36 Ronald van Vollenhoven,9,12 on behalf of the NORD-STAR study group For numbered affiliations see ABSTRACT and rheumatoid factor or anti-citrullinated protein end of the article. OBJECTIVE antibody positivity, or increased C reactive protein. Correspondence to: To evaluate and compare benefits and harms of three INTERVENTIONS M L Hetland biological treatments with different modes of action Randomised 1:1:1:1, stratified by country, sex, Copenhagen Center for versus active conventional treatment in patients with Arthritis Research, Center and anti-citrullinated protein antibody status. -

2019 Medicare Medical Injectable Criteria

2019 INJECTABLE DRUG PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA UCare Medicare Classic (HMO-POS) UCare Value (HMO-POS) UCare Essentials Rx (HMO-POS) UCare Standard (HMO-POS) UCare Prime (HMO POS) Care Core with Fairview & North Memorial (HMO-POS) Care Advantage with Fairview & North Memorial (HMO-POS) EssentiaCare Secure (PPO) EssentiaCare Grand (PPO) These drugs require authorization before dispensing and administering. Please reference the Injectable Drug Authorization Guide to determine if authorization will need be obtained through the member’s Part D or Part B benefit. The prior authorization criteria contained in this document may not apply to UCare Medicare products if Medicare requires different coverage criteria. If Medicare requires different coverage criteria, the applicable NCD or LCD will apply. Updated: 01/2019 Actemra Products Affected • ACTEMRA INTRAVENOUS PA Criteria Criteria Details Covered Uses All medically accepted indications not otherwise excluded plus patients already started on tocilizumab for a covered use. Castleman's disease. Still's disease. Exclusion Concurrent use with a biologic DMARD or targeted synthetic Criteria DMARD (e.g., Xeljanz, Otezla). Required Diagnosis, previous medication use Medical Information Age Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), patients 18 years of age and older. Restrictions Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (PJIA) and Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (SJIA), patients 2 years of age and older. All other conditions, 18 years of age and older. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), patients 2 years of age and older. Prescriber For Castleman's disease must be prescribed by or in consultation Restrictions with an oncologist or hematologist. For RA, PJIA, SJIA, and Still's Disease, must be prescribed by or in consultation with a rheumatologist. -

Certolizumab Pegol for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Effective in Combination with Methotrexate Or As Monotherapy

Drug Evaluation Certolizumab pegol for rheumatoid arthritis: effective in combination with methotrexate or as monotherapy TNF plays an important role in several disease states, including rheumatoid arthritis. Biologic agents that specifically target TNF have revolutionized the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Traditional anti-TNF agents have provided significant clinical benefit. However, patient responses to these agents in clinical practice may be variable and additional agents are needed. Certolizumab pegol is the only PEGylated anti-TNF that is now approved for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. This article summarizes the published efficacy, safety and patient-reported health outcome results for certolizumab pegol in the treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis who have experienced an inadequate response to treatment with DMARDs, including methotrexate. KEYWORDS: certolizumab pegol methotrexate monotherapy RAPID Philip J Mease rheumatoid arthritis TNF-a Seattle Rheumatology Associates, Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is estimated to affect long-term disability, with biologic therapy in Swedish Medical Center, 5 million people worldwide [1] with 0.3–1% of combination with MTX providing superior Seattle, WA 98104, USA the population in industrialized countries suf- clinical and radiological efficacy over mono- Tel.: +1 206 386 2000; fering from RA [2]. The development of RA is therapy [12]. However, individual patient Fax: +1 206 386 2083; associated with increasing age and female gen- responses to biologic therapies are variable [email protected] der, with the prevalence among women being and achieving remission depends on the initial approximately two-times greater than in men [3]. level of disease activity. Some patients never Although the etiology of RA remains unclear, achieve a response and for those who respond the inflammation and joint damage associated initially, efficacy to one or all of the available with the disease are known to be partially medi- agents may decline.