Cutaneous Adverse Effects of Biologic Medications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genmab and ADC Therapeutics Announce Amended Agreement for Camidanlumab Tesirine (Cami)

Genmab and ADC Therapeutics Announce Amended Agreement for Camidanlumab Tesirine (Cami) Media Release Copenhagen, Denmark and Lausanne, Switzerland, October 30, 2020 • ADC Therapeutics to continue the development and commercialization of Cami • Genmab to receive mid-to-high single-digit tiered royalty Genmab A/S (Nasdaq: GMAB) and ADC Therapeutics SA (NYSE: ADCT) today announced that they have executed an amended agreement for ADC Therapeutics to continue the development and commercialization of camidanlumab tesirine (Cami). The parties first entered into a collaboration and license agreement in June 2013 for the development of Cami, an antibody drug conjugate (ADC) which combines Genmab’s HuMax®-TAC antibody targeting CD25 with ADC Therapeutics’ highly potent pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) warhead technology. Under the terms of the 2013 agreement, the parties were to determine the path forward for continued development and commercialization of Cami upon completion of a Phase 1a/b clinical trial. ADC Therapeutics previously announced that Cami achieved an overall response rate of 86.5%, including a complete response rate of 48.6%, in Hodgkin lymphoma patients in this trial who had received a median of five prior lines of therapy. Cami is currently being evaluated in a 100-patient pivotal Phase 2 clinical trial intended to support the submission of a Biologics License Application (BLA) to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The trial is more than 50 percent enrolled and ADC Therapeutics anticipates reporting interim results in the first half of 2021. “We have a long-standing relationship with the ADC Therapeutics team and believe they are an ideal partner for the ongoing development and potential commercialization of Cami,” said Jan van de Winkel, Ph.D., Chief Executive Officer of Genmab. -

BAFF-Neutralizing Interaction of Belimumab Related to Its Therapeutic Efficacy for Treating Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-03620-2 OPEN BAFF-neutralizing interaction of belimumab related to its therapeutic efficacy for treating systemic lupus erythematosus Woori Shin1, Hyun Tae Lee1, Heejin Lim1, Sang Hyung Lee1, Ji Young Son1, Jee Un Lee1, Ki-Young Yoo1, Seong Eon Ryu2, Jaejun Rhie1, Ju Yeon Lee1 & Yong-Seok Heo1 1234567890():,; BAFF, a member of the TNF superfamily, has been recognized as a good target for auto- immune diseases. Belimumab, an anti-BAFF monoclonal antibody, was approved by the FDA for use in treating systemic lupus erythematosus. However, the molecular basis of BAFF neutralization by belimumab remains unclear. Here our crystal structure of the BAFF–belimumab Fab complex shows the precise epitope and the BAFF-neutralizing mechanism of belimumab, and demonstrates that the therapeutic activity of belimumab involves not only antagonizing the BAFF–receptor interaction, but also disrupting the for- mation of the more active BAFF 60-mer to favor the induction of the less active BAFF trimer through interaction with the flap region of BAFF. In addition, the belimumab HCDR3 loop mimics the DxL(V/L) motif of BAFF receptors, thereby binding to BAFF in a similar manner as endogenous BAFF receptors. Our data thus provides insights for the design of new drugs targeting BAFF for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. 1 Department of Chemistry, Konkuk University, 120 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05029, Republic of Korea. 2 Department of Bio Engineering, Hanyang University, 222 Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 04763, Republic of Korea. These authors contributed equally: Woori Shin, Hyun Tae Lee, Heejin Lim, Sang Hyung Lee. -

ADC Therapeutics SA (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 6-K REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER PURSUANT TO RULE 13a-16 OR 15d-16 UNDER THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the month of February 2021. Commission File Number: 001-39071 ADC Therapeutics SA (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Biopôle Route de la Corniche 3B 1066 Epalinges Switzerland (Address of principal executive office) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F: Form 20-F ☒ Form 40-F Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(1): ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(7): ☐ SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized. ADC Therapeutics SA Date: February 4, 2021 By: /s/ Michael Forer Name: Michael Forer Title: Executive Vice President & General Counsel EXHIBIT INDEX Exhibit No. Description 99.1 Press release dated February 4, 2021 Exhibit 99.1 ADC Therapeutics Completes Enrollment in Pivotal Phase 2 Clinical Trial of Camidanlumab Tesirine (Cami) in Relapsed or Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma Interim results anticipated in the first half of 2021 LAUSANNE, Switzerland, February 4, 2021 – ADC Therapeutics SA (NYSE:ADCT), a late clinical-stage oncology-focused biotechnology company pioneering the development and commercialization of highly potent and targeted antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) for patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors, today announced completion of enrollment in the pivotal Phase 2 clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of camidanlumab tesirine (Cami, formerly ADCT-301) in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. -

Pharmacologic Considerations in the Disposition of Antibodies and Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Preclinical Models and in Patients

antibodies Review Pharmacologic Considerations in the Disposition of Antibodies and Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Preclinical Models and in Patients Andrew T. Lucas 1,2,3,*, Ryan Robinson 3, Allison N. Schorzman 2, Joseph A. Piscitelli 1, Juan F. Razo 1 and William C. Zamboni 1,2,3 1 University of North Carolina (UNC), Eshelman School of Pharmacy, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; [email protected] (J.A.P.); [email protected] (J.F.R.); [email protected] (W.C.Z.) 2 Division of Pharmacotherapy and Experimental Therapeutics, UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; [email protected] 3 Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-966-5242; Fax: +1-919-966-5863 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 22 December 2018; Published: 1 January 2019 Abstract: The rapid advancement in the development of therapeutic proteins, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), has created a novel mechanism to selectively deliver highly potent cytotoxic agents in the treatment of cancer. These agents provide numerous benefits compared to traditional small molecule drugs, though their clinical use still requires optimization. The pharmacology of mAbs/ADCs is complex and because ADCs are comprised of multiple components, individual agent characteristics and patient variables can affect their disposition. To further improve the clinical use and rational development of these agents, it is imperative to comprehend the complex mechanisms employed by antibody-based agents in traversing numerous biological barriers and how agent/patient factors affect tumor delivery, toxicities, efficacy, and ultimately, biodistribution. -

Xolair/Omalizumab

Therapeutic/Humanized Antibodies ELISA Kits ‘Humanized antibodies” are ‘Animal Antibodies’ that have been modified by recombinant DNA-technology to reduce the overall content of the animal- portion of immunoglobulin so as to increase acceptance by humans or minimize ‘rejection’. By analogy, if the hands of a mouse is actually responsible for grabbing things then ‘humanized-mouse’ will only contain the ‘mouse hands’ and the rest of the body will be human. Since the size of the IgGs is similar in mouse and human, the size of the native mouse IgG and the ‘humanized IgG’ does not significantly change. Antigen recognition property of an antibody actually resides in small portion of the IgG molecule called the ‘antigen binding site or Fab’. Therefore, humanized antibodies contain the minimal portion from the Fab or the epitopes necessary for antigen binding. The process of "humanization of antibodies" is usually applied to animal (mouse) derived monoclonal antibodies for therapeutic use in humans (for example, antibodies developed as anti-cancer drugs). Xolair (Anti-IgE) is an example of humanized IgG. The portion of the mouse IgG that remains in the ‘humanized IgG’ may be recognized as foreign by humans and may result into the generation of “Human Anti-Drug Antibodies (HADA). The presence of anti-Drug antibody (e.g., Human Anti-Rituximab IgG) that may limit the long-term usage the humanized antibody (Rituximab). Not all monoclonal antibodies designed for human therapeutic use need be humanized since many therapies are short-term. The International Nonproprietary Names of humanized antibodies end in “-zumab”, as in “omalizumab”. Humanized antibodies are distinct from chimeric or fusion antibodies. -

ADC Therapeutics SA (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 6-K REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER PURSUANT TO RULE 13a-16 OR 15d-16 UNDER THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the month of July, 2020. Commission File Number: 001-39071 ADC Therapeutics SA (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Biopôle Route de la Corniche 3B 1066 Epalinges Switzerland (Address of principal executive office) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F: Form 20-F ☒ Form 40-F Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(1): ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(7): ☐ SIGNATURE Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized. ADC Therapeutics SA Date: July 6, 2020 By: /s/ Dominique Graz Name: Dominique Graz Title: General Counsel EXHIBIT INDEX Exhibit No. Description 99.1 Press release dated July 6, 2020 Exhibit 99.1 ADC Therapeutics Announces U.S. Food and Drug Administration Has Lifted Partial Clinical Hold on Pivotal Phase 2 Clinical Trial of Camidanlumab Tesirine Lausanne, Switzerland — July 6, 2020 — ADC Therapeutics SA (NYSE:ADCT), a clinical-stage oncology-focused biotechnology company leading the development and commercialization of next-generation antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) with highly potent and targeted pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimer technology, today announced that the U.S. -

Comparative Effectiveness of Pembrolizumab Vs. Nivolumab In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Comparative efectiveness of pembrolizumab vs. nivolumab in patients with recurrent or advanced NSCLC Pengfei Cui1,2,4, Ruixin Li2,4, Ziwei Huang3,2,4, Zhaozhen Wu3,2, Haitao Tao2, Sujie Zhang2 & Yi Hu1,2,3* The efcacies of pembrolizumab and nivolumab have never been directly compared in a real-world study. Therefore, we sought to retrospectively evaluate the objective response rate (ORR) and the progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with recurrent or advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in a real-world setting. This study included patients with recurrent or advanced NSCLC diagnosed between September 1, 2015 and August 31, 2019, who were treated with programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors at the Cancer Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. PFS was estimated for each treatment group using Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests. The multivariate analysis of PFS was performed with Cox proportional hazards regression models. A total of 255 patients with advanced or recurrent NSCLC treated with PD-1 inhibitors were identifed. The ORR was signifcantly higher in the pembrolizumab group than in the nivolumab group, while PFS was not signifcantly diferent between the two groups. Subgroup analysis showed that the ORR was signifcantly higher for pembrolizumab than for nivolumab in patients in the frst-line therapy subgroup and in those in the combination therapy as frst-line therapy subgroup. Survival analysis of patients receiving combination therapy as second- or further-line therapy showed that nivolumab had better efcacy than pembrolizumab. However, the multivariate analysis revealed no signifcant diference in PFS between patients treated with pembrolizumab and those treated with nivolumab regardless of the subgroup. -

Avelumab (Bavencio®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy

1 Avelumab (Bavencio®) Prior Authorization Drug Coverage Policy Effective Date: 9/1/2020 Revision Date: n/a Review Date: 3/6/2020 Lines of Business: Commercial Policy type: Prior Authorization This Drug Coverage Policy provides parameters for the coverage of avelumab (Bavencio®). Consideration of medically necessary indications are based upon U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications, recommended uses within the Centers of Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) five recognized compendia, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Drugs & Biologics Compendium (Category 1 or 2A recommendations), and peer-reviewed scientific literature eligible for coverage according to the CMS, Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, Chapter 15, section 50.4.5 titled, “Off-Label Use of Anti-Cancer Drugs and Biologics.” This policy evaluates whether the drug therapy is proven to be effective based on published evidence-based medicine. Drug Description 1-2 Avelumab is a fully human IgG1 monoclonal antibody that specifically binds to PD-L1. This binding blocks the interaction between PD-L1 and its receptors, PD-1 and B7.1. Blocking PD-1 and B7.1 interaction restores anti-tumor T-cell function. FDA Indications 1 Avelumab is FDA indicated for the following: Treatment of metastatic Merkel Cell carcinoma (MCC) in adults and children ≥ 12 years of age. Treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma in patients who have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy or have disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy. First-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in combination with axitinib Coverage Determinations 1,3 Avelumab will require prior authorization. -

Bavencio; INN-Avelumab

10 December 2020 EMA/CHMP/3166/2021 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment report Bavencio International non-proprietary name: avelumab Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/004338/II/0018 Note Variation assessment report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. Official address Domenico Scarlattilaan 6 ● 1083 HS Amsterdam ● The Netherlands Address for visits and deliveries Refer to www.ema.europa.eu/how-to-find-us An agency of the European Union Send us a question Go to www.ema.europa.eu/contact Telephone +31 (0)88 781 6000 © European Medicines Agency, 2021. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Table of contents 1. Background information on the procedure .............................................. 7 1.1. Type II variation ................................................................................................ 7 1.2. Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................... 8 2. Scientific discussion ................................................................................ 9 2.1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1. Problem statement .......................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. About the product ........................................................................................... 9 2.1.3. The development programme/compliance with CHMP guidance/scientific -

International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis 2020 Update

VIEWS & REVIEWS OPEN ACCESS LEVEL OF RECOMMENDATION International Consensus Guidance for Management of Myasthenia Gravis 2020 Update Pushpa Narayanaswami, MBBS, DM, Donald B. Sanders, MD, Gil Wolfe, MD, Michael Benatar, MD, Correspondence Gabriel Cea, MD, Amelia Evoli, MD, Nils Erik Gilhus, MD, Isabel Illa, MD, Nancy L. Kuntz, MD, Janice Massey, MD, Dr. Narayanaswami Arthur Melms, MD, Hiroyuki Murai, MD, Michael Nicolle, MD, Jacqueline Palace, MD, David Richman, MD, and pnarayan@ Jan Verschuuren, MD bidmc.harvard.edu Neurology® 2021;96:114-122. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000011124 Abstract Objective To update the 2016 formal consensus-based guidance for the management of myasthenia gravis (MG) based on the latest evidence in the literature. Methods In October 2013, the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America appointed a Task Force to develop treatment guidance for MG, and a panel of 15 international experts was convened. The RAND/UCLA appropriateness method was used to develop consensus recommendations pertaining to 7 treatment topics. In February 2019, the international panel was reconvened with the addition of one member to represent South America. All previous recommendations were reviewed for currency, and new consensus recommendations were developed on topics that required inclusion or updates based on the recent literature. Up to 3 rounds of anonymous e-mail votes were used to reach consensus, with modifications to recommendations between rounds based on the panel input. A simple majority vote (80% of panel members voting “yes”) was used to approve minor changes in grammar and syntax to improve clarity. Results The previous recommendations for thymectomy were updated. New recommendations were developed for the use of rituximab, eculizumab, and methotrexate as well as for the following topics: early immunosuppression in ocular MG and MG associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. -

Annex I Summary of Product Characteristics

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT YERVOY 5 mg/ml concentrate for solution for infusion 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each ml of concentrate contains 5 mg ipilimumab. One 10 ml vial contains 50 mg of ipilimumab. One 40 ml vial contains 200 mg of ipilimumab. Ipilimumab is a fully human anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody (IgG1κ) produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells by recombinant DNA technology. Excipients with known effect: Each ml of concentrate contains 0.1 mmol sodium, which is 2.30 mg sodium. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Concentrate for solution for infusion (sterile concentrate). Clear to slightly opalescent, colourless to pale yellow liquid that may contain light (few) particulates and has a pH of 7.0 and an osmolarity of 260-300 mOsm/kg. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Melanoma YERVOY as monotherapy is indicated for the treatment of advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma in adults, and adolescents 12 years of age and older (see section 4.4). YERVOY in combination with nivolumab is indicated for the treatment of advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma in adults. Relative to nivolumab monotherapy, an increase in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for the combination of nivolumab with ipilimumab is established only in patients with low tumour PD-L1 expression (see sections 4.4 and 5.1). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) YERVOY in combination with nivolumab is indicated for the first-line treatment of adult patients with intermediate/poor-risk advanced renal cell carcinoma (see section 5.1). -

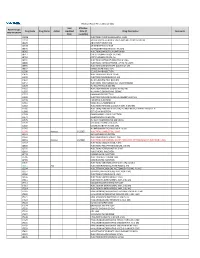

2021 Prior Authorization List Part B Appendix a (PDF)

Medicare Part B PA List Effective 2021 Last Effective Part B Drugs: Drug Code Drug Name Action Updated Date (if Drug Description Comments STEP THERAPY Date available) C9050 INJECTION, EMAPALUMAB-LZSG, 1 MG C9122 MOMETASONE FUROATE SINUS IMPLANT 10 MCG SINUVA J0129 ABATACEPT INJECTION J0178 AFLIBERCEPT INJECTION J0570 BUPRENORPHINE IMPLANT 74.2MG J0585 INJECTION,ONABOTULINUMTOXINA J0717 CERTOLIZUMAB PEGOL INJ 1MG J0718 CERTOLIZUMAB PEGOL INJ J0791 INJECTION CRIZANLIZUMAB-TMCA 5 MG J0800 INJECTION, CORTICOTROPIN, UP TO 40 UNITS J0896 INJECTION LUSPATERCEPT-AAMT 0.25 MG J0897 DENOSUMAB INJECTION J1300 ECULIZUMAB INJECTION J1428 INJECTION ETEPLIRSEN 10 MG J1429 INJECTION GOLODIRSEN 10 MG J1442 INJ FILGRASTIM EXCL BIOSIMIL J1447 INJECTION, TBO-FILGRASTIM, 1 MICROGRAM J1459 INJ IVIG PRIVIGEN 500 MG J1555 INJECTION IMMUNE GLOBULIN 100 MG J1556 INJ, IMM GLOB BIVIGAM, 500MG J1557 GAMMAPLEX INJECTION J1558 INJECTION IMMUNE GLOBULIN XEMBIFY 100 MG J1559 HIZENTRA INJECTION J1561 GAMUNEX-C/GAMMAKED J1562 INJECTION; IMMUNE GLOBULIN 10%, 5 GRAMS J1566 INJECTION, IMMUNE GLOBULIN, INTRAVENOUS, LYOPHILIZED (E.G. P J1568 OCTAGAM INJECTION J1569 GAMMAGARD LIQUID INJECTION J1572 FLEBOGAMMA INJECTION J1575 INJ IG/HYALURONIDASE 100 MG IG J1599 IVIG NON-LYOPHILIZED, NOS J1602 GOLIMUMAB FOR IV USE 1MG J1745 INJ INFLIXIMAB EXCL BIOSIMILR 10 MG J1930 Remove 1/1/2021 INJECTION, LANREOTIDE, 1 MG J2323 NATALIZUMAB INJECTION J2350 INJECTION OCRELIZUMAB 1 MG J2353 Remove 1/1/2021 INJECTION, OCTREOTIDE, DEPOT FORM FOR INTRAMUSCULAR INJECTION, 1 MG J2357 INJECTION, OMALIZUMAB,