Stephanietincher2009.Pdf (7.874Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway Near P Street, Ca

ROCK CREEK AND ROCK CREEK'S BRIDGES Dumbarton Bridge William Howard Taft Bridge (8) Duke Ellington Bridge (9) POTOMAC PARKWAY Washington, D.C. The monumental bridges arching over Rock Creek contribute Dumbarton Bridge, at Q Street, is one of the parkway's most The William Howard Taft Bridge, built 1897-1907, is probably The current bridge at Calvert Street replaced a dramatic iron greatly to the parkway's appearance. Partially concealed by the endearing structures. It was designed by the noted architect the most notable span on the parkway. The elegant arched truss bridge built in 1891 to carry streetcars on the Rock Creek surrounding vegetation, they evoke the aqueducts and ruins Glenn Brown and completed in 1915. Its curving form structure carrying Connecticut Avenue over Rock Creek valley Railway line. When the parkway was built, it was determined m&EWAIl2 UN IIA^M1GN¥ found in romantic landscape paintings. In addition to framing compensates for the difference in alignment between the was Washington's first monumental masonry bridge. Its high that the existing bridge was unable to accommodate the rise in vistas and providing striking contrasts to the parkway's natural Washington and Georgetown segments of Q Street. cost and elaborate ornamentation earned it the nickname "The automobile traffic. The utilitarian steel structure was also features, they serve as convenient platforms for viewing the Million Dollar Bridge." In 1931 it was officially named after considered detrimental to the parkway setting. verdant parkway landscape. They also perform the utilitarian The overhanging pedestrian walkways and tall, deep arches former president William Howard Taft, who had lived nearby. -

Newsletterjanuary 2017

NewsletterJANUARY 2017 VOLUME XLII | ISSUE 1 | WWW.CAGTOWN.ORG CROSSING THE POTOMAC TUESDAY, JANUARY 24 RECEPTION AT 7PM, PROGRAM AT 7:30PM MALMAISON – 3401 WATER STREET ith so few access points to George- town, we have to make the most of Wwhat we have. Come to Malmai- son, at the foot of Key Bridge, on January 24th to hear what is going on with the bridge renovations, the gondola project, the Metro and even bus lanes. Joe Sternlieb from the Georgetown Business Improvement District (BID) will present the thinks. If there is consensus to move forward, it is being renovated. We will get an update findings from a recent exploratory study on an environmental impact study would take a from the Key Bridge Renovation team – Sean a gondola that would take riders from the few years to complete, and then construction Moore and Joyce Tsepas will tell us where the Rosslyn Metro to Georgetown. The experts would probably take another few years, putting construction stands and how it will impact determined in their report that the gondola the completion of the gondola in the Georgetowners’ daily lives (both on land and was "feasible." The gondola "would provide early to mid-2020’s. water) and what we have to look forward to. improved transit for workers, residents, the Joe will also tell us the latest on plans for Metro – The Popal family has graciously agreed to university and tourists." It anticipates the the current 2040 plan shows a possible crossing minimum daily ridership to be 6,500. The host us at the swank Malmaison locat- under the Potomac and a Georgetown Metro ed right next to Key Bridge at 3401 cost would be about $80 to $90 million to station at the cost of about $2 billion. -

Georgetown Retaining Wall/Exorcist Steps

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: ____Georgetown Retaining Wall/Exorcist Steps_______________________ Other names/site number: ______________________________________ Name of related multiple property listing: ______N/A_____________________________________________________ (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: __Square 1202, Lot 840; East of Reservation 392__________________ City or town: _Washington________ State: __DC__________ County: ____________ Not For Publication: Vicinity: ____________________________________________ ________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards -

~Ock Creek Park Di Trict of Columbia

hi toric re ource tudy ~OCK CREEK PARK DI TRICT OF COLUMBIA ON P.11CROFf lM PlfASE RETURN TD: l[ CAL INR>RMATION COITER Co or ca . DOMR SERVICE CENTER rol 2-3/:;...cc -. NATIONAL. PARK SERVICE historic resource study august 1990 by William Bushong \ ROCK CREEK PARK • DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE iii I e TABLE OF CONTENTS I ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS I ix PART I: HISTORY OF 1HE lAND AREA AND USES OF ROCK CREEK PARK. DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA. CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION I 1 CHAPTER II: SUMMARY OF THE PREHISTORY AND HISTORY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. PRIOR TO 1790. I 7 Aboriginal Inhabitants, European Contact. and Trade. I 8 Settlement and Development of Towns in the Washington Area. I 12 NOTES I 19 CHAPfER III: "ROCK CREEK IN OLDEN DAYS": TIIE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF TIIE LAND AREA OF ROCK CREEK PARK. 1790-1890. I 22 Rock Creek Park in the L'Enfant-Ellicott Plan for the National Capital. I 23 The Settlement of Upper Rock Creek Before the Civil War. I 25 The Milling Industry Along Rock Creek. / 34 The Civil War Period, 1861-1865. I 40 Nineteenth Century Land Uses After 1865. / 46 NOTES I 52 CHAPTER IV: TIIE ESTABLISHMENT OF ROCK CREEK PARK. I 61 Legislative Background to the Creation of Rock Creek Park. I 63 The Rock Creek Park Commission. I 73 NOTES I 79 iv CHAPTERV: THE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT OF ROCK CREEK PARK. 1890-1933. I 85 Years of Transition. I 85 Park Planning and the Centennial of the Nation's Capital. -

Congressional Record-Senate. ·

' 1892. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. 3031 people-to the Committee on Election of President, Vice-Presi LISTS OF GOVERNMENT EMPLOYEs. dent, and Representatives in Congress. The VICE-PRESIDENT laid before the Senate a communica Also, two petitions of certain citizens of Idaho, in favor of tion from the Commissioner of Labor, transmitting, in response electing Unit-ed States Senators by the people-to the Select to ~resolution of the 24th ultimo, i.Jiformation in regard to em Committee on Election of President, Vice-President, and Repre ployes in that office notspecificallyappropriated for; which, with sentatives in Congress. the accompanying papers, was referred to theCmnmitteeon Civil Also, petition of the Woman s Christian Temperance Union Service and Retrenchment, and ordered to be printed. of Idaho, 180 signatures, against opening any exposition on Sun day where Government funds are used-to the Select Committee PETITIONS AND MEMORIALS. on the Columbian Exposition. Mr. HARRIS. I present a petition of the members of the Also, petition of National Woman's Christian Temperance Nashville (Tenn.) Academy of Medicine and practicing physi Union of Idaho, against opening any exposition on Sunday where cians of Nashville, signed by Dr. Briggs and some 40 others, United States funds are used-to the Select Committee on the praying for the establishment of a department of health, with a . I Columbian Exposition. cabinet officer at its head. I move that the petition be relerred Also, petition of certain citizens of Idaho, in favor of a postal to the Committee on Epidemic Diseases. savings bank-to the Committee on the Post-Office and Post The motion was agreed to. -

Newslettermarch 2017

NewsletterMARCH 2017 VOLUME XLII | ISSUE 3 | WWW.CAGTOWN.ORG Georgetown Beautification: TALKING TRASH (& RODENTS) WEDNESDAY, MARCH 22 framework of the Georgetown Community RECEPTION AT 7PM; PROGRAM AT 7:30 PM Partnership. HEALY FAMILY CENTER – The speakers on March 22 will be: Gerard GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY CAMPUS Brown, the Program Manager in the Rodent Control Division at the DC Department of Patrick Clawson, Co-Chair: Rats, Trash & Recycling Health; Sonya Chance, the Ward 2 inspector for the DC Department of Public Works’ wo of the most frequently cited con- Solid Waste Education and Enforcement Pro- cerns in our recent member survey gram (SWEEP), and Cory Peterson from Twere rats and trash. At our Wednesday, Georgetown University’s Office of Neigh- March 22 meeting, a panel of experts will borhood Life. discuss what can be done to combat these persistent problems. Our host for the evening is Georgetown Uni- versity. The meeting will be held in the Social Georgetown is a lovely neighborhood not Room of the Healy Family Student Center. only for people but, unfortunately, also Come for an informative discussion and for rodents. Hear why our village has so check out this modern, attractive facility. A many rats and what you can do to help the reception will begin at 7pm, followed by the DC Department of Health reduce the rat panel discussion at 7:30. population. The Healey Family Student Center is on the In the last few years, both the DC Govern- south side of campus. For directions (walking, ment and Georgetown University have devot- driving, cycling), see maps.georgetown.edu. -

Mapdirections.Pdf

This walk starts in Georgetown and utilizes the Lovers Lane Walkway to reach Massachusetts Avenue and view some of the diplomatic residences in Washington, DC. It returns via a well-utilized paved trail through Rock Creek Park and a short walk through a portion of the Georgetown historic district. Since the Lovers Lane portion of this walk is isolated it is suggested that this walk may not be appropriate for singles. Only on-street parking is available and it is somewhat limited in this area. 1. Lovers Lane serves as the entrance to Dumbarton Oaks Park from R Street NW. Look for the sign marked 'Dumbarton Oaks Park' on R Street just east of the Dumbarton Oaks mansion at 31st Street. The paved path goes down a steep hill with a wall on the left and Montrose Park on the right. 2. There are intersecting paths to the left and right at the bottom of the hill and the pavement ends. Continue straight and follow the dirt path as it curves to the right and climbs a grade. The path to the left enters Dumbarton Oaks Park. The path to the right heads down towards Rock Creek. 3. After the next turn to the left Rock Creek can be seen below when the leaves are off the trees. 4. The building to the left as you near Massachusetts Avenue is the Italian embassy. 5. Cross Massachusetts Avenue to Rock Creek Drive on the opposite side. There is a crosswalk to the left. Follow the sidewalk on the left side of Rock Creek Drive. -

Rock Creek & Potomac Parkway Historic District

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "X" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway Historic District other names Lower Rock Creek Valley Historic District 2. Location street & number Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway 0 not for publication city or town Washln::3g;!,:to=.:n=--_______--:- ___- ______________ 0 vicinity 20242 20037 20007 state -=-D~.C:....._. ______ code DC county nJa code 001 zip 2000820009 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property /81 meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Download The

R2_Georgetown_Guide_Cover.indd 1 6/17/19 12:18 PM Welcome to Georgetown Photo Credit: Sam Kittner for the Georgetown BID B GEORGETOWNDC.COM MAP ON PAGE 18 Photo Credit: Sam Kittner for the Georgetown BID 2 About the Georgetown BID Georgetown is a lot of things to a lot of people. 4 Georgetown Today Cobblestone streets and cupcake tours. Waterfront 6 Georgetown History picnics and political watering holes. Canal history and 8 Getting Here charming boutiques. Founded in 1751, 40 years before 10 Food & Drink the nation’s capital, DC’s original neighborhood has a 18 Georgetown Map storied history—but half the fun is writing your own. 22 Shopping Today this National Historic District is where the past meets 30 Arts, Culture & Entertainment the present, with more than 470 shops, restaurants and 32 Health, Beauty & Relaxation institutions set against the backdrop of Georgetown’s 34 Neighborhood Events unique architecture and quaint streets. Start exploring! 36 Fitness & Recreation Cover Photo Collage Credits: Sam Kittner and Kate Warren for the Georgetown BID 37 Services & Points of Interest The Georgetown Guide & Map is a yearly publication of the Georgetown BID produced by Essential Media Partners. Copyright 2019. While every effort is made to ensure the timeliness and accuracy of all information and material, Essential Media Partners assumes no responsibility for accuracy, completeness, errors, changes, or omissions. For inquiries or requests, please call 866-698-1108. GEORGETOWNDC.COM MAP ON PAGE 18 1 About the BID About the Georgetown Business Improvement District Stay Connected The Georgetown BID is a nonprofit organization dedicated Georgetown is open 24 hours at www.georgetowndc.com to protecting and enhancing the accessibility, attractiveness and overall appeal of Georgetown. -

Rock Creek Trail Final EA

Rock Creek Park Multi-Use Trail Rehab ilit ation Affected Environment CHAPTER 3: AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT This “Affected Environment” chapter of the EA describes existing environmental conditions in the proposed project area. These conditions serve as a baseline for understanding the resources that could be impacted by implementation of the proposed action. The resource topics presented in this chapter, and the organization of these topics, correspond to the resources discussions discussed in “Chapter 4: Environmental Consequences.” 3.1. SOILS Geomorphic processes shape the landscape of Rock Creek Park, which consists of a steep, rugged stream valley and rolling hills. The park straddles the boundary of two physiographic provinces: the Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain. The transitional zone between the two provinces is known as the Fall Line. The Piedmont is composed of hard, crystalline igneous and metamorphic rocks, extending to the west of Rock Creek Park. Rolling hills of the region were formed through folding, faulting, metamorphism, uplifting and erosion. Piedmont soils are highly weathered and generally well-drained. The Atlantic Coastal Plain is a generally flat region composed of sediment deposits from the past 100 million years, extending to the east of Rock Creek Park. The sediment deposits have been continually reworked by fluctuating sea levels and erosive forces. As a result, typical soils of the region are well drained sands or sandy loams (NPS 2009). The United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has compiled an inventory of District of Columbia soils, in order to deliver science based soil information. The locations, descriptions, recommended uses and limitations of soils are identified in The Soil Survey of the District of Columbia (USDA 1976). -

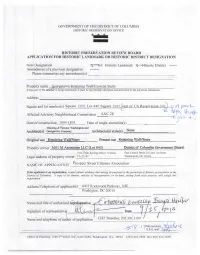

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES The D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites is the official list of historic properties maintained by the Government of the District of Columbia. These properties are deemed worthy of recognition and protection for their contribution to the cultural heritage of the city that is both national capital and home to more than a half million residents. The Inventory had its beginnings in 1964 and remains a work in progress. It is being continually expanded as additional survey and research supports new designations and more complete documentation of existing listings. At present, there are about 600 entries, covering more than 535 landmark buildings, 100 other structures, and 100 parks and places. There are also about two dozen designated building clusters and another two dozen neighborhood historic districts encompassing an estimated 23,500 buildings. Complete professional documentation of such a large number of properties to current preservation standards is an extensive undertaking that is still incomplete. For this reason, some listings in the Inventory provide a full description of the historic property, while others provide outline information only. Organization: The layout of the Inventory is designed to promote understanding of significant properties within their historic context. Designations are grouped by historical time period and theme, rather than being listed in alphabetical order. For organizational purposes, the historical development of the District of Columbia is divided into six broad historical eras, with separate sections on early Georgetown and Washington County, the port town and outlying countryside that were separate legal entities within the District for most of the 19th century. -

KENNEDY CENTER EXPANSION CONNECTION PROJECT Section 106 Assessment of Effects

KENNEDY CENTER EXPANSION CONNECTION PROJECT Section 106 Assessment of Effects Prepared by ROBINSON & ASSOCIATES, INC. June 3, 2016 Kennedy Center Expansion Connection Project Section 106 ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Project Background .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Section 106 Consultation Overview ................................................................................................. 7 2.0 IDENTIFICATION OF HISTORIC PROPERTIES ............................................................................................ 8 2.1 Area of Potential Effects ................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Identification of Resources ............................................................................................................... 8 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF EFFECTS ..................................................................................................................... 20 3.1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 20 3.2 Description