Module 3: Defects, Diffusion and Conduction in Ceramics Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ionic Conduction in the Solid State

J. Chem. Sci., Vol. 118, No. 1, January 2006, pp. 135–154. © Indian Academy of Sciences. Ionic conduction in the solid state P PADMA KUMAR and S YASHONATH Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Solid state ionic conductors are important from an industrial viewpoint. A variety of such conductors have been found. In order to understand the reasons for high ionic conductivity in these sol- ids, there have been a number of experimental, theoretical and computational studies in the literature. We provide here a survey of these investigations with focus on what is known and elaborate on issues that still remain unresolved. Conductivity depends on a number of factors such as presence of interstitial sites, ion size, temperature, crystal structure etc. We discuss the recent results from atomistic computer simula- tions on the dependence of conductivity in NASICONs as a function of composition, temperature, phase change and cation among others. A new potential for modelling of NASICON structure that has been proposed is also discussed. Keywords. Ionic conduction; solid state; atomistic computer simulations; NASICON structure. 1. Introduction 2. A brief history of superionic conductors There exist many solids with high ionic conductivity The study of ionic conduction in solid state origi- (>10–4 W–1 cm–1) and they are of immense use in di- nated way back in 1838 when Faraday discovered verse technological applications. Some of these solids that PbF2 and Ag2S are good conductors of electri- which are also good electronic conductors are often city.2,3 These solids are, the first ever discovered referred to as ‘mixed conductors’, while the term solid electrolyte and intercalation electrode respecti- ‘superionic conductor’ or ‘fast ion conductor’ is re- vely. -

Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries: Mechanisms and Properties Governing Ion Conduction

Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries: Mechanisms and Properties Governing Ion Conduction The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Bachman, John Christopher, Sokseiha Muy, Alexis Grimaud, Hao-Hsun Chang, Nir Pour, Simon F. Lux, Odysseas Paschos, et al. “Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries: Mechanisms and Properties Governing Ion Conduction.” Chemical Reviews 116, no. 1 (January 13, 2016): 140–162. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00563 Publisher American Chemical Society (ACS) Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/109539 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. A Review of Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes for Lithium Batteries: Mechanisms and Properties Governing Ion Conduction John Christopher Bachman1,2,‡, Sokseiha Muy1,3,‡, Alexis Grimaud1,4,‡, Hao-Hsun Chang1,4, Nir Pour1,4, Simon F. Lux5, Odysseas Paschos6, Filippo Maglia6, Saskia Lupart6, Peter Lamp6, Livia Giordano1,4,7 and Yang Shao-Horn1,2,3,4 * 1Electrochemical Energy Laboratory, 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, 3Department of Materials Science and Engineering, 4Research Laboratory of Electronics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States 5BMW Group Technology Office USA, Mountain View, California 94043, United -

ABSTRACT METAL ISOTOPE FRACTIONATION INDUCED by FAST ION CONDUCTION in NATURAL and SYNTHETIC WIRE SILVER by Calvin J. Anderson A

ABSTRACT METAL ISOTOPE FRACTIONATION INDUCED BY FAST ION CONDUCTION IN NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC WIRE SILVER by Calvin J. Anderson An unusual metal isotope fractionation has been observed in association with the growth of wire silver, whose unique texture and morphology can be explained by superionic + conduction of Ag in Ag2S. This constitutes the first recognition of mass migration by fast ion conduction in nature. Stable Ag isotope analysis revealed natural wire silver is normally enriched in the heavy isotope 109Ag, while common fractionation mechanisms would predict the opposite. In synthetic wires grown at high temperature (>450°C), this fractionation is amplified by an order of magnitude more than expected by any known isotope effect. This may indicate a previously unrecognized isotope fractionation mechanism associated with superionic conductors in nature and in general, which would have important implications for the geochemistry of ore deposits, as well as fast-ion technologies including atomic switches and solid-state ion batteries. METAL ISOTOPE FRACTIONATION INDUCED BY FAST ION CONDUCTION IN NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC WIRE SILVER A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science by Calvin J. Anderson Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2018 Advisor: John Rakovan Reader: Mark Krekeler Reader: Elisabeth Widom ©2018 Calvin J. Anderson This Thesis titled METAL ISOTOPE FRACTIONATION INDUCED BY FAST ION CONDUCTION IN NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC WIRE SILVER by Calvin -

Ab Initio Investigation of the Stability of Electrolyte/Electrode Interfaces in All-Solid-State Na Batteries

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title Ab initio investigation of the stability of electrolyte/electrode interfaces in all-solid-state Na batteries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2jb9x0h6 Journal Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 7(14) ISSN 2050-7488 Authors Lacivita, V Wang, Y Bo, SH et al. Publication Date 2019 DOI 10.1039/c8ta10498k Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Materials Chemistry A View Article Online PAPER View Journal Ab initio investigation of the stability of electrolyte/ electrode interfaces in all-solid-state Na batteries† Cite this: DOI: 10.1039/c8ta10498k Valentina Lacivita, *a Yan Wang, b Shou-Hang Boc and Gerbrand Ceder*ad All-solid-state batteries show great potential for achieving high energy density with less safety problems; however, (electro)chemical issues at the solid electrolyte/electrode interface may severely limit their performance. In this work, the electrochemical stability and chemical reactivity of a wide range of potential Na solid-state electrolyte chemistries were investigated using density functional theory calculations. In general, lower voltage limits are predicted for both the reduction and oxidation of Na compounds compared with those of their Li counterparts. The lower reduction limits for the Na compounds indicate their enhanced cathodic stability as well as the possibility of stable sodium metal cycling against a number of oxides and borohydrides. With increasing Na content (or chemical potential), improved cathodic stability but also reduced anodic stability are observed. An increase in the oxidation voltage is shown for Na polyanion systems, including borohydrides, NaSICON-type oxides, and Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. -

Practical Challenges and Future Perspectives of All-Solid-State Lithium-Metal Batteries, Chem (2018)

Please cite this article in press as: Xia et al., Practical Challenges and Future Perspectives of All-Solid-State Lithium-Metal Batteries, Chem (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2018.11.013 Review Practical Challenges and Future Perspectives of All-Solid-State Lithium-Metal Batteries Shuixin Xia,1,4 Xinsheng Wu,1,4 Zhichu Zhang,1 Yi Cui,2,3,* and Wei Liu1,* The fundamental understandings and technological innovations in lithium-ion The Bigger Picture batteries are essential for delivering high energy density, stable cyclability, Lithium-ion batteries are one of and cost-effective energy storages with the growing demands in the applica- the most promising energy- tions of electrical vehicles and smart grid. Solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) are storage devices for their high more promising than organic liquid electrolyte in terms of excellent safety in energy density, superior cycling developing lithium-metal anode as well as other high-capacity cathode chemis- stability, and light weight. tries, such as sulfur and oxygen. Considerable efforts have been made to give However, the state-of-the-art birth to the superionic conductors with ionic conductivities higher than lithium-ion batteries cannot satisfy À À 10 3 Scm 1 at room temperature. However, the high interfacial impedances the rising demand of high energy from the poor compatibility of SSEs with electrodes limit their practical applica- density. Advanced lithium tions, which are discussed in this review. Furthermore, the recent advances batteries based on metallic and critical challenges for all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries based on the lithium anodes could provide cathode materials of lithium-intercalation compounds, sulfur, and oxygen are higher energy density and thus overviewed, and their future developments are also prospected. -

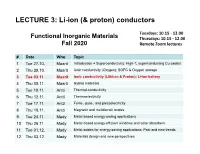

LECTURE 3: Li-Ion (& Proton) Conductors

LECTURE 3: Li-ion (& proton) conductors Tuesdays: 10.15 - 12.00 Functional Inorganic Materials Thursdays: 10.15 - 12.00 Fall 2020 Remote Zoom lectures # Date Who Topic 1 Tue 27.10. Maarit Introduction + Superconductivity: High-Tc superconducting Cu oxides 2 Thu 29.10. Maarit Ionic conductivity (Oxygen): SOFC & Oxygen storage 3 Tue 03.11. Maarit Ionic conductivity (Lithium & Proton): Li-ion battery 4 Thu 05.11. Maarit Hybrid materials 5 Tue 10.11. Antti Thermal conductivity 6 Thu 12.11. Antti Thermoelectricity 7 Tue 17.11. Antti Ferro-, pyro-, and piezoelectricity 8 Thu 19.11. Antti Magnetic and multiferroic oxides 9 Tue 24.11. Mady Metal-based energy-saving applications 10 Thu 26.11. Mady Metal-based energy-efficient windows and solar absorbers 11 Tue 01.12. Mady Metal oxides for energy-saving applications: Past and new trends 12 Thu 03.12. Mady Materials design and new perspectives # DATE TOPIC & KEYWORDS 1 27.10. (High-Tc) Superconductivity New-material design, Multi-layered crystal structure, Mixed-valency, Oxygen nonstoichiometry 2 29.11. Ionic conductivity: Oxygen Oxygen vacancies, Redox-active cations, Mixed valency, Cation substitutions (isovalent/aliovalent), Crystal symmetry, Oxygen storage, SOFC 3 03.11. Ionic conductivity: Hydrogen & Lithium Water absorption & Oxide/hydroxide, Li-ion battery, Solid-state electrolytes 4 05.11. Hybridmaterials Inorganic-organic materials, MOF, ALD/MLD, Layer-engineering LECTURE EXERCISE 3 1. Which useful function could be anticipated for an oxygen-deficient oxide material that can absorb water? Explain ! 2. Explain why a layered crystal structure is useful for Li-ion battery electrode materials. 3. What happens to (a) structure, (b) electrical conductivity, and (c) ) Li-ion conductivity of Li3PO4 when nitrogen is introduced into it to form LiPON (LixPOyNz) ? Why these are important changes ? NOTE: There will be an additional question in the Exercise 4 which is partly related to the topics covered in Lecture 3. -

Enhancing the Ionic Conductivity of Solid State Electrolytes by Oxide Glass Doping

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Enhancing the ionic conductivity of solid state electrolytes by oxide glass doping Yue Zhou Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Zhou, Yue, "Enhancing the ionic conductivity of solid state electrolytes by oxide glass doping" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7051. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7051 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Enhancing the ionic conductivity of solid state electrolytes by oxide glass doping Yue Zhou Thesis submitted to Benjamin M. Statler College of Engineering and Mineral Resources at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master In Mechanical Engineering Xingbo Liu, Ph.D., Chairperson and Advisor Xueyan Song, Ph.D. Bingyun Li, Ph.D. Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Morgantown, West Virginia 2016 Keywords: Lithium, ion conductivity, LLTO, oxide glass doping Copyright 2016 [Yue Zhou] Abstract As the increasing use of lithium ion secondary batteries in practical application, solid state electrolyte attracted lots of attention since it’s a crucial part for the lithium ion secondary batteries. -

Ion Hopping and Constrained Li Diffusion Pathways in the Superionic State of Antifluorite Li2o

entropy Article Ion Hopping and Constrained Li Diffusion Pathways in the Superionic State of Antifluorite Li2O Ajay Annamareddy and Jacob Eapen * Department of Nuclear Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-919-515-5952 Academic Editors: Giovanni Ciccotti, Mauro Ferrario and Christof Schuette Received: 21 March 2017; Accepted: 15 May 2017; Published: 18 May 2017 Abstract: Li2O belongs to the family of antifluorites that show superionic behavior at high temperatures. While some of the superionic characteristics of Li2O are well-known, the mechanistic details of ionic conduction processes are somewhat nebulous. In this work, we first establish an onset of superionic conduction that is emblematic of a gradual disordering process among the Li ions at a characteristic temperature Ta (~1000 K) using reported neutron diffraction data and atomistic simulations. In the superionic state, the Li ions are observed to portray dynamic disorder by hopping between the tetrahedral lattice sites. We then show that string-like ionic diffusion pathways are established among the Li ions in the superionic state. The diffusivity of these dynamical string-like structures, which have a finite lifetime, shows a remarkable correlation to the bulk diffusivity of the system. Keywords: Li2O; atomistic simulations; antifluorites; superionics; string-like; ionic conduction; diffusion 1. Introduction Lithium oxide (Li2O) has long been of interest because of its potential application as a tritium-breeding material in fusion reactors [1]. Li2O is also a superionic (or fast-ion) conductor, attaining liquid-like ionic conductivities within the solid state [2]. It is one of the simplest Li-based superionic conductors having just two species [3–7]. -

Atomic Scale Simulations of the Solid Electrolyte Li7la3zr2o12 By

Atomic Scale Simulations of the Solid Electrolyte Li7La3Zr2O12 by Seungho Yu A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Mechanical Engineering) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donald Siegel, Chair Professor Udo Becker Assistant Professor Neil Dasgupta Associate Professor Jeff Sakamoto Seungho Yu [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-3912-6463 © Seungho Yu 2018 Acknowledgements First, I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my advisor, Professor Don Siegel, for his invaluable mentorship during my Ph.D. studies. Without his guidance and persistent help this dissertation would not have been possible. I am also deeply grateful to Professor Jeff Sakamoto, whose research insights have been greatly beneficial and helpful to me. I additionally thank Professors Neil Dasgupta and Udo Becker for their valuable advice and service on my committee. I would like to thank Dr. Jeff Wolfenstine, Dr. Travis Thompson, Dr. Asma Sharafi, and Eric Kazyak for their experimental efforts. I am also grateful to members of the Siegel research group for their supportive discussions. This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Advanced Battery Material Research (BMR) program under Grant DE-EE-0006821 and Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy (ARPA-e), grant no. DE-AR0000653. I also acknowledge financial support from the Kwanjeong Educational Foundation. Last but not least, I am greatly indebted to my parents and my wife, Sooyeon Kim, for their warm love, encouragement, and endless support. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables............................................................................................................................ vii List of Figures .......................................................................................................................... -

Review of Multivalent Metal Ion Transport in Inorganic and Solid Polymer Electrolytes

batteries Review Review of Multivalent Metal Ion Transport in Inorganic and Solid Polymer Electrolytes Lauren F. O’Donnell and Steven G. Greenbaum * Department of Physics and Astronomy, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York, NY 10065, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.:+1-212-772-4973 Abstract: The lithium ion battery, with its high energy density and low reduction potential, continues to enchant researchers and dominate the landscape of energy storage systems development. However, the demands of technology in modern society have begun to reveal limitations of the lithium energy revolution. A combination of safety concerns, strained natural resources and geopolitics have inspired the search for alternative energy storage and delivery platforms. Traditional liquid electrolytes prove precarious in large scale schemes due to the propensity for leakage, the potential for side reactions and their corrosive nature. Alternative electrolytic materials in the form of solid inorganic ion conductors and solid polymer matrices offer new possibilities for all solid state batteries. In addition to the engineering of novel electrolyte materials, there is the opportunity to employ post-lithium chemistries. Utility of multivalent cation (Ca2+, Mg2+, Zn2+ and Al3+) transport promises a reduction in cost and increase in safety. In this review, we examine the current research focused on developing solid electrolytes using multivalent metal cation charge carriers and the outlook for their application in all solid state batteries. Keywords: all solid state battery; multivalent metal cation conductor; solid polymer electrolyte; solid inorganic electrolyte Citation: O’Donnell, L.F.; Greenbaum, S.G. Review of Multivalent Metal Ion Transport in 1. -

Lithium Garnets: Synthesis, Structure, Li+ Conductivity, Li+ Dynamics and Applications ⇑ S

Progress in Materials Science 88 (2017) 325–411 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Progress in Materials Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pmatsci Lithium garnets: Synthesis, structure, Li+ conductivity, Li+ dynamics and applications ⇑ S. Ramakumar, C. Deviannapoorani, L. Dhivya, Lakshmi S. Shankar, Ramaswamy Murugan Department of Physics, Pondicherry University, Puducherry 605 014, India article info abstract Article history: Inorganic solid fast Li+ conductors based batteries are expected to overcome the limitations Received 3 April 2017 over safety concerns of flammable organic polymer electrolytes based Li+ batteries. Hence, Accepted 6 April 2017 an all-solid-state Li+ battery using non-flammable solid electrolyte have attracted much Available online 8 April 2017 attention as next-generation battery. Therefore, in the development of all-solid-state lithium rechargeable batteries, it is important to search for a solid electrolyte material that Keywords: has high Li+ conductivity, low electronic conductivity, fast charge transfer at the electrode Electrochemical energy storage devices interface and wide electrochemical window stability against potential electrodes and Rechargeable lithium battery technology lithium metal. Hence, significant research effort must be directed towards developing Solid fast Li+ conductors + Garnet structured fast Li+ conductors novel fast Li conductors as electrolytes in all-solid-state lithium batteries. Among the reported inorganic solid Li+ conductive oxides, garnet-like structural compounds received considerable attention in recent times for potential application as electrolytes in all-solid- state lithium batteries. The focus of this review is to provide comprehensive overview towards the importance of solid fast lithium ion conductors, advantages of lithium garnets over other ceramic lithium ion conductors and understanding different strategies on syn- thesis of lithium garnets. -

Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Studies of Fast Ion Conductors

Chapter 7 Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics Studies of Fast Ion Conductors Zhuoying Zhu, Zhi Deng, Iek-Heng Chu, Balachandran Radhakrishnan, and Shyue Ping Ong 7.1 Introduction Fast ion conductors are a technologically important class of materials that have extensive applications in energy storage, ion-selective electrodes and sensors. For example, fast oxide conductors such as yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and CaO- doped zirconia have been used as solid electrolytes in solid oxide fuel cells and oxy- gen sensors in automotive applications, respectively [1–4]. In next-generation all- solid-state rechargeable alkali-ion (lithium-ion and sodium-ion) batteries (SSBs), the key enabling material is the solid electrolyte, which is a fast alkali-ion conductor. SSBs are safer and potentially more energy dense at the system level than traditional lithium-ion batteries based on flammable organic liquid electrolytes, and the search for novel superionic alkali conductors is a topic of immense current interest [5–10]. As their name implies, fast ion conductors exhibit high ionic mobility in at least one species, such as oxide (O2) or alkali ions (LiC/NaC). There are in general two broad classes of ab initio techniques for the study of ionic diffusion and conduction in materials in the scientific literatures: transition state methods [11] (e.g., nudged elastic band [12] and kinetic Monte Carlo [13]) and molecular dynamics simulations [14–16]. In this chapter, we will focus on the latter, i.e., ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation, and its application in the study and design of fast ion conductors. A more general discussion of all techniques can be found in several excellent reviews in the literature [5, 17, 18].