Freedom, Foreign Policy, and Public Opinion: a Strategy for Fostering Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Advisors in Vietnam: 1963

Military Advisors in Vietnam: 1963 Topic: Vietnam Grade Level: 9-12 Subject Area: US History after World War II Time Required: 1 class period Goals/Rationale In the winter of 1963, the eyes of most Americans were not on Vietnam. However, Vietnam would soon become a battleground familiar to all Americans. In this lesson plan, students analyze a letter to President Kennedy from a woman who had just lost her brother in South Vietnam and consider Kennedy’s reply, explaining his rationale for sending US military personnel there. Essential Question: What were the origins of US involvement in Vietnam prior to its engagement of combat troops? Objectives Students will: analyze primary sources. discuss US involvement in the Vietnam conflict prior to 1963. evaluate the “domino theory” from the historical perspective of Americans living in 1963. Connections to Curriculum (Standards) National Standards: National Center for History in the Schools Era 9 - Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s), 2B - The student understands United States foreign policy in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Era 9, 2C - The student understands the foreign and domestic consequences of US involvement in Vietnam. Massachusetts Frameworks US II.20 – Explain the causes, course and consequences of the Vietnam War and summarize the diplomatic and military policies of Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Prior Knowledge Students should have a working knowledge of the Cold War. They should be able to analyze primary sources. Prepared by the Department of Education and Public Programs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum Historical Background and Context After World War II, the French tried to re-establish their colonial control over Vietnam, the most strategic of the three states comprising the former Indochina (Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos). -

Rhetoric and Reality

History Studies Volume 13 History Studies Volume 13 information on Walsh, but he was still dismissed by the Catholic Church. After his sacking Jimmy Walsh was Rhetoric and Reality -A History of the Formation employed as a hospital porter, but spent the rest of his life of the 'Domino Theory' trying to enter various religious orders, becoming a novice in a Luke Butterly Benedictine Monastery. He was unsuccessful in these attempts Gaps between rhetoric and reality in U.S. foreign however because he had once been married and was now policy have often been large; indeed such gaps might be said to constitute a defining characteristic of this separated. Jimmy Walsh died after a prolonged illness on 12 nation's diplomacy. I March 1977. and was buried in Sydney. He had never returned 76 to treland. When U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced the 'domino theory' at a news conference in 1954, he was not announcing a radical departure in Washington's understanding of the emerging situation in Indochina. Rather, he was making public aspects of U.S. foreign policy that had been in the making since the end of World War ll, which in turn interacted with older themes. This essay will first situate this 'theory' in the historiography of the Vietnam War in order to contextualise what follows. It will then map the formation of the domino theory from 1945 to 1954, and will briefly look at the broader implications of such an approach in foreign policy. This will be achieved by examining the secondary literature on the various historical events covered and reviewing the relevant primary sources. -

Key Concepts Chart (The Cold War)

Unit 8, Activity 1, Key Concepts Chart Key Concepts Chart (The Cold War) Key Concept + ? - Explanation Extra Information Containment The attempt of one nation to The United States attempts block another nation from to stop the spread of spreading its influence to other communism during the Cold nations. War era. Marshall Plan In 1947, Secretary of State The nations that accepted George Marshall proposed an United States aid had to economic plan to rebuild remove all trade barriers Europe after WWII. and agree to cooperate economically with each other. Truman The United States gave Greece Following the war Great Doctrine and Turkey over $400 million in Britain originally tried to aid to prevent the spread of send economic and military communism in Europe. aid to Greece and Turkey to prevent the spread of communism. containment deterrence domino theory brinkmanship “Iron Curtain” speech Truman Doctrine Marshall Plan Berlin airlift NATO Blackline Masters, U.S. History Page 8-1 Unit 8, Activity 1, Key Concepts Chart Key Concept + ? - Explanation Extra Information Warsaw Pact Korean War Suez Crisis Sputnik the Second Red Scare Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 Fair Deal McCarthyism military- industrial complex space race U-2 incident Bay of Pigs invasion Cuban Missile Crisis Berlin Wall Limited Test Blackline Masters, U.S. History Page 8-2 Unit 8, Activity 1, Key Concepts Chart Key Concept + ? - Explanation Extra Information Ban Treaty domino theory Vietnam War Gulf of Tonkin Resolution Tet Offensive My Lai Massacre Vietnamization Cambodia War Powers Act silent majority Détente Poland’s Solidarity movement Strategic Defense Initiative Intermediate- Range Nuclear Forces Treaty Blackline Masters, U.S. -

United States History

UNITED STATES HISTORY For each multiple choice question, fill in the appropriate location on the scantron 1. Which impact did Title IX had on educational institutions 8. The Watergate Scandal is appropriately described by in the United States? which statement? A. use of quotas for enrollment A. It concerned the Nixon’s’ administration attempt to B. creation of standardized testing goals cover up a burglary at the Democratic National C. equal funding of men’s and women’s athletics Committee headquarters D. government-funded school vouchers B. It involved the illegal establishment of government agencies to set and enforce campaign standards 2. What event during the 1970s resulted in the United C. It involved the choice of the Reagan Administration States increasing its regulation of nuclear power plants? to secretly supply aid to the Contra rebels in A. the signing of the SALT treaty Nicaragua B. North Korea’s announcement that it had nuclear D. It concerned the secret leasing of federally-owned weapons oil rigs to western ranches C. the incident at Three Mile Island D. restrictions created by the UN Atomic Energy 9. Nixon’s name for the many Americans who supported the Commission government and longed for an end to the violence & turmoil of the 1960s was the 3. Which US president regarded universal health care as a A. counterculture major issue for the federal government to resolve? B. hippies A. Jimmy Carter C. silent majority B. Ronald Reagan D. détente C. George H.W. Bush D. Bill Clinton 10. President Jimmy Carter was instrumental in creating a peace accord known as the 4. -

Lynch Modern History E-Learning Cold War Overview

• Summer 1945 • Followed the Yalta Conference in Feb. • US, UK, & Soviet Union continue plans for postwar Europe & division of Germany • Soviets block access to Berlin in 1948 • US & UK respond with the Berlin Airlift • Soviets demand Western forces leave Berlin • US refuses and the Soviets begin building the Berlin Wall in 1961 • Begun by President Truman in 1947 • US will give economic & military aid to stop spread of communism • Aligns with domino theory that communism would spread • Similar to Germany, Korea left divided after WW2 • North Korea invades the South in 1950 • US leads UN forces to support South Korea • Cease-fire and DMZ created at the 38th Parallel in 1953 • Long, slow building guerrilla war from 1950s to 1973 • Increased with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964 • The 1968 Tet Offensive turned many against the war in the US • US involvement ended in 1973 but Vietnam united under communism in 1975 • Pres. Eisenhower threatens “massive retaliation” if provoked • Hopeful this would deter any Soviet strike • Like a game of chicken • “Mutually Assured Destruction” if bombs ever used • Pres. Kennedy made it part of his “Flexible Response” • US discovers Soviet missile buildup in Cuba in October 1962 • Results in a 13-day standoff • After a US blockade, an agreement is reached • Moscow-Washington hotline established • An easing of tensions after years of both nations on edge • Begun by Nixon & Brezhnev in the 1970s • More talks & treaties until the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 • Strategic Arms Limitation Talks • US -

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961) and the 1950S I. Dwight

American History Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953-1961) and the 1950s I. Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961) –Republican A. Pre-Presidential Biography 1. Childhood –born in Denison, Texas and raised in Abilene, Kansas 2. Army –West Point, WWII, President of Columbia University, and NATO Commander B. Presidential Biography 1. Campaign “Korea, Communism, and Corruption” - defeated Adlai Stevenson –1952 & 1956 2. The “Hidden Hand” President 3. Health and Age Issues C. IKE Fun Facts II. The “New Look” Foreign Policy –John Foster Dulles (Secretary of State) A. The “New Look” policy guidelines –but still stopping communism 1. Domino Theory 2. Brinkmanship –“Victory goes to him who can keep his nerve to the last 15 minutes.” 3. Massive Retaliation –no initial attack will occurred out of fear of US response 4. Nuclear Buildup –“more bang for your buck” 5. Covert Operations –using the Central Intelligence Agency B. Asia 1. Korean War –“I shall go to Korea” –Armistice signed (July 27, 1953) 2. Iran -Operation AJAX (August 19, 1953) –Shah Reza Pahlavi (US-backed leader) A. Eisenhower Doctrine (1957) =containment + Middle East 3. Indochina –domino theory –fighting communism in Southeast Asia A. Lost North Vietnam to communism B. Keep South Vietnam capitalist and supported SV President Ngo Dinh Diem 4. Taiwan Crisis -People’s Republic of China vs. Taiwan –PRC attacked Taiwan A. US protected Taiwan -Mutual Defense Treaty C. Latin America 1. Guatemala (1954) -Operation Success –CIA overthrew rightful government over bananas 2. Cuba -President Fidel Castro took control of Cuba January 1, 1959 –now communist D. Soviet-American Relations –Premier Nikita Khrushchev (1953-1964) 1. -

1. Agent Orange 2. Camp David Accords 3. Détente 4. Domino

American II – Unit 7 – Vocabulary Words 1. Agent orange 2. Camp David Accords 3. Détente 4. Domino Theory 5. Doves 6. Feminism 7. Geneva Accords 8. Hawks 9. Ho Chi Minh 10. Ho Chi Minh Trail 11. Iran Hostage Crisis 12. Kent State Shootings 13. Mandate 14. My Lai Massacre 15. Napalm 16. Ngo Dinh Diem 17. Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) 18. pardon 19. realpolitik 20. SALT II 21. Search and Destroy Missions 22. Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) 23. Tet Offensive 24. The Pentagon Papers 25. Tonkin Gulf Resolution 26. Vietcong 27. Vietminh 28. Vietnamization 29. Watergate 30. Woodward and Berstein AMERICAN II - UNIT 7 – Notes Moving Toward Conflict France Controlled Vietnam since late 1800’s, but the peasants disliked foreign rule, followed Ho Chi Minh, the communist leader of Vietnam throughout the Vietnam War, who was exiled to China Japan forced out France in WWII, but faced problems with peasants with return of Ho Chi Minh who started Vietminh (Vietnamese word to describe their dislike of foreign rule, and desire to rule themselves) After Japanese defeat in WWII, France wanted to take back over Vietnam Vietnamese fought back with Ho Chi Minh 1. What was Vietminh and why did the Vietnamese want it? Moving Toward Conflict (cont) US afraid of Domino Theory - This is an American belief that if one country falls to communism the surrounding countries to fall to communism as well soon afterwards The French were beaten and surrendered in northwest Vietnam in 1954 Geneva Accords – This agreement between America and Vietnam temporary divided Vietnam along 17th parallel in 1954. -

Communist Bloc Expansion in the Early Cold War: Challenging Realism, Refuting Revisionism Author(S): Douglas J

Communist Bloc Expansion in the Early Cold War: Challenging Realism, Refuting Revisionism Author(s): Douglas J. Macdonald Reviewed work(s): Source: International Security, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter, 1995-1996), pp. 152-188 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2539142 . Accessed: 09/01/2012 01:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security. http://www.jstor.org Connunist Bloc DouglasJ. Macdonald Expansionin the EarlyCold War Challenging Realism, RefutingRevisionism W as there ever a unifiedcommunist threat facing the UnitedStates during the Cold War?Or did U.S. decision-makersmisperceive Soviet and communistbloc "defensive- ness"and "caution"as expansionistthreats? Did U.S. leaders,realizing that the Sovietsand theirideological allies posed no securitythreat to theUnited States and its allies,create such claimsfor various domestic political reasons? Such questionshave dominatedanalyses of the Cold Warin theUnited States for thepast thirtyyears. To thesurprise of some and theconsternation of others, thedemise of theCold Warand theresulting flow of new evidencefrom the Eastin recentyears has reinvigoratedmany of these arguments over its origins, theprimary responsibility for its creation, and U.S. -

HIST 122: Western Civilization II

University of South Dakota HIST 122: Western Civilization II Causes and consequences of the Second World War What were the major European and non-European nations involved in WWII? What were the initial events leading to WWII? What might have been done by various countries to prevent WWII? What was the role of German expansion in Austria, the Sudetenland, and Poland in causing WWII? Why did Adolph Hitler believe Germany should undertake such expansion? How was the Rome-Berlin Axis achieved? Explain the conflicting relationship between Germany and the Soviet Union during WWII. What finally caused the United States to enter WWII? Explain the situation of rule in France during WWII? Who were the main military and political leaders involved in WWII? What were the reasons for the United States use of two atomic bombs? Provide a brief overview of the events of WWII and the pivotal battles in both the pacific theatre and in Europe. Provide a general overview of the greatest extent of Nazi occupation in Europe during the war. Why did Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union fail? How was peace settled after WWII? Which countries were the major beneficiaries after WWII? What were some of the major practical problems that required immediate attention in the wake of the devastation of WWII? What were the human costs of WWII? How did this divide up among the various nations? How did it divide up between civilians and soldiers? How did the settlement of WWII differ from that of WWI? What is the connection between WWII and the United Nations and the Council of Europe? How did WWII affect the long-term situation in the Middle East? Development of this review sheet was made possible by funding from the US Department of Education through South Dakota’s EveryTeacher Teacher Quality Enhancement grant. -

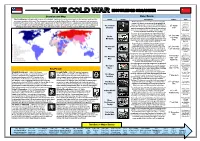

Overview and Map Major Events Key People Timeline of Major Events

Overview and Map Major Events The Cold War was a long period of open, yet restrained, tension between the democracies of the western world and the Event Image Description Date/s Fact communist countries of the east. The democratic west was led by the United States, whilst the communist east was spear- The Truman Doctrine was an American foreign policy headed by the Soviet Union – the two world superpowers at the time. Whilst the two superpowers never directly declared created with the aim of countering Soviet geopolitical The Doctrine led to the war on one another, they fought indirectly via proxy wars, an arms race, and the space race, in order to gain political and expansion. Announced to congress by President Harry S. th The Truman 12 March formation of ideological dominance. The map below shows the extent of their alliances in 1980, towards the end of the Cold War. Truman, the doctrine alleged that communist totalitarian Doctrine 1947 NATO, an regimes represented a significant threat to international alliance that is peace. As a result, American support would be provided still in effect. to countries threatened by Soviet communism. During multinational occupation of post-World War II It proved to be Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies’ 24th June 1948 a PR disaster Berlin railway, road and canal access to parts of Berlin under for Stalin, who – 12th May Blockade western control, in response to western introduction of the had to remove Deutsche mark. Via the ‘Berlin Airlift’, Allied planes were 1949 the blockade in able to deliver vital supplies to Berliners. -

Unit 6 Study Guide Name: Date: 1. Which of the Following American

Unit 6 Study Guide Name: Date: 1. Which of the following American foreign policy 3. In 1968, the number of Americans who felt theories held that if one nation in a region fell that United States troops should withdraw from to communism, the whole region would fall to Vietnam increased significantly. Which of the communism? following events was most important in causing this shift in public opinion? A. Domino Theory B. Marshall Plan A. The Tonkin Gulf incident C. Roosevelt Corollary D. Truman Doctrine B. The Tet Offensive C. The fall of Dien Bien Phu D. The siege of Khe Sanh 2. How did the fear of communism during the 1950s affect the United States? A. There was more public support for the repeal 4. Which of the following was a primary cause of of segregation laws. the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union? B. There was more public support for the buildup of nuclear weapons. A. a competition for political influence over other C. The government supported the rise of countries independence movements in Southeast Asia. B. direct, armed conflict between the two nations D. The government supported the overthrow of C. a deep reduction in military expenditures repressive dictatorships in Latin America. D. the founding of the United Nations page 1 5. Which of the following congressional actions, 7. Refer to the newspaper article below to answer the passed during the Vietnam conflict, gave President following question. Lyndon B. Johnson the authority to send troops to Vietnam without a declaration of war? Saigon, April 30, 1975 A. -

SOCIAL SCIENCE an Introduction to the History of the Cold War I. FROM

SOCIAL SCIENCE An Introduction to the History of the Cold War I. FROM ALLIES TO RIVALS: WORLD WAR II ENDS AND THE COLD WAR BEGINS 30% A. Origins of the Cold War 1. Clashing Ideals a. American Ideals: Wilsonian Democracy and American Exceptionalism b. Soviet Ideals: Marxist-Leninist Revolution and Stalinism 2. World War II: U.S.-Soviet Alliance a. The Basis of the U.S.-Soviet Wartime Alliance b. The American Wartime Experience c. The Soviet Wartime Experience 3. Postwar Planning a. The Yalta Conference b. The Potsdam Conference c. The United Nations (San Francisco, April 25–June 26, 1945) B. The Cold War Begins 1. The Early Cold War in Europe a. The Iron Curtain b. Soviet Satellites 2. Containment a. George F. Kennan: Architect of Containment b. Political Containment: The Truman Doctrine c. Economic Containment: The Marshall Plan to the Berlin Blockade d. Military Containment: NATO to NSC-68 e. Ideological Containment: Propaganda and the Campaign of Truth 3. The Early Cold War in Asia a. Decolonization and Independence b. Mao Zedong and China c. The Korean War 4. Nuclear War a. The Arms Race and Deterrence b. Atomic Warfare Strategy: Massive Retaliation to Mutually Assured Destruction C. New Leadership 1. The U.S.: Eisenhower and the Cold War Consensus 2. The U.S.S.R.: The Death of Stalin and the Rise of Khrushchev II. THE COLD WAR’S EFFECTS ON DOMESTIC POLITICS AND CULTURE IN AMERICA 20% A. The Enemy Within: “Disloyalty” and the Fear of Communist Subversion 1. Loyalty Programs and the FBI 2 2.