Private Information Trading and Enhanced Accounting Disclosure of Bank Stocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

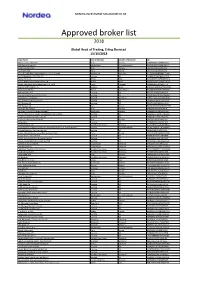

External Borkers List

NORDEA INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT AB Approved broker list 2018 Global Head of Trading, Erling Skorstad 15/10/2018 Legal Name City of Domicile Country of Domicile LEI ABG Sundal Collier ASA Oslo Norway 2138005DRCU66B8BNY04 ABN Amro Group NV Amsterdam The Netherlands BFXS5XCH7N0Y05NIXW11 Arctic Securities AS Oslo Norway 5967007LIEEXZX4RVS72 Aurel BGC SAS Paris France 5RJTDGZG4559ESIYLD31 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Melbourne Australia JHE42UYNWWTJB8YTTU19 AUTONOMOUS RESEARCH LLP London UK 213800LBM6PT85IGM996 Banca IMI S.p.A Milan Italy QV4Q8OGJ7OA6PA8SCM14 Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria S.A Bilbao Spain K8MS7FD7N5Z2WQ51AZ71 Banco Português de Investimento, S.A. (BPI) Porto Portugal 213800NGLJLXOSRPK774 BANCO SANTANDER S.A Madrid Spain 5493006QMFDDMYWIAM13 Bank Vontobel AG Zurich Switzerland 549300L7V4MGECYRM576 Barclays Bank PLC London UK G5GSEF7VJP5I7OUK5573 Barclays Capital Securities Limited London UK K9WDOH4D2PYBSLSOB484 Bayerische Landesbank Munich Germany VDYMYTQGZZ6DU0912C88 BCS Prime Brokerage Limited London UK 213800UU8AHE2B6QUI26 BGC Brokers LP London UK ZWNFQ48RUL8VJZ2AIC12 BNP Paribas SA Paris France R0MUWSFPU8MPRO8K5P83 Carnegie AS Norway Oslo Norway 5967007LIEEXZX57BC18 Carnegie Investment Bank AB (publ) Stockholm Sweden 529900BR5NZNQZEVQ417 China International Capital Corporation (UK) Limited London UK 213800STG3UV87MDGA96 Citigroup Global Markets Limited London UK XKZZ2JZF41MRHTR1V493 Clarksons Platou Securities AS Oslo Norway 5967007LIEEXZXA40G44 CLSA (UK) London UK 213800VZMAGVIU2IJA72 Commerzbank AG Frankfurt -

Fast and Secure Transfers – Fact Sheet

FAST AND SECURE TRANSFERS – FACT SHEET NEW ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SERVICE, “FAST” FAST (Fast And Secure Transfers) is an electronic funds transfer service that allows customers to transfer SGD funds almost immediately between accounts of the 24 participating banks and 5 non-financial institutions (NFI) in Singapore. FAST was originally launched on 17 March 2014 and included only bank participants. From 8th February onwards, FAST will also be available to the 5 NFI participants. FAST enables almost immediate receipt of money. You will know the status of the transfer by accessing your bank account via internet banking or via notification service offered by the participating bank or NFI. FAST is available anytime, 24x7, 365 days. Payment Type Receipt of Payments FAST Almost Immediate, 24x7 basis Cheque Up to 2 business days eGIRO Up to 3 business days Types of accounts that you can use to transfer funds via FAST (Updated on 25 Jan 2021) FAST can be used to transfer funds between customer savings accounts, current accounts or e-wallet accounts. For some banks, the service can also be used for other account types (see table below). Other Account types that you can use FAST Participating Bank to transfer funds via FAST Transfer from Transfer to (Receive) (Pay) 1 ANZ Bank MoneyLine MoneyLine 2 Bank of China Credit Card Credit Card MoneyPlus MoneyPlus 3 The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ - - 4 BNP Paribas - - 5 CIMB Bank - - 6 Citibank NA - - 7 Citibank Singapore Limited - - 8 DBS Bank/POSB Credit Card Credit Card Cashline Cashline 9 Deutsche Bank - - 10 HL Bank - - 11 HSBC - - 12 HSBC Bank (Singapore) Limited - - 13 ICICI Bank Limited Singapore - - 14 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Limited Debit Card Debit Card Credit Card 15 JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. -

Gauging the Potential in Thai Banking* Introduction Overview

Financial Services Back on the investment radar: Gauging the potential in Thai banking* Introduction Overview The Thai banking sector is attracting increasing international • Economy set to rebound as confidence returns following interest as the market opens up to foreign investment and the return to democracy. the return to democracy helps to reinvigorate consumer • Banking sector recording steady growth. Strong confidence and demand. opportunities for the development of retail lending. Bad debt ratios have gradually declined and the balance • Foreign banks account for 12% of the market by assets and sheets of Thailand’s leading banks have strengthened 10% of lending by value.7 Strong presence in high-value considerably since the Asian financial crisis of 1997.1 niche segments including auto finance, mortgages and The moves to Basel II and IAS 39 are set to enhance credit cards. transparency and risk management within the sector, while accelerating the demand for foreign capital and expertise. • Organic entry strategies curtailed by licensing and branch opening restrictions. Reforms already in place include the ‘single presence’ rule, which by seeking to limit cross-ownership of the country’s • Acquisition of minority stakes in existing banks proving banks is leading to increased consolidation and the opening increasingly popular. Ceiling on foreign holdings set to be up of sizeable holdings for new investment. The Financial raised to 49%, though there are no firm plans to allow Sector Master Plan and forthcoming Financial Institution outright control. Business Act (2008), which will come into force in August • Demand for capital and foreign expertise is encouraging 2008, could ease restrictions on branch openings and the more domestic banks to seek foreign investment, especially size of foreign investment holdings. -

STOXX Asia 100 Last Updated: 03.07.2017

STOXX Asia 100 Last Updated: 03.07.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 256.2 1 1 JP3633400001 6900643 7203.T 690064 Toyota Motor Corp. JP JPY Y 128.5 2 2 TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.6 3 3 JP3902900004 6335171 8306.T 659668 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group JP JPY Y 83.5 4 4 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 77.2 5 5 JP3436100006 6770620 9984.T 677062 Softbank Group Corp. JP JPY Y 61.7 6 7 JP3735400008 6641373 9432.T 664137 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C JP JPY Y 58.7 7 8 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 58.2 8 6 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 52.6 9 12 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 52.0 10 10 JP3890350006 6563024 8316.T 656302 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou JP JPY Y 48.3 11 15 INE040A01026 B5Q3JZ5 HDBK.BO IN00CH HDFC Bank Ltd IN INR Y 45.4 12 13 JP3854600008 6435145 7267.T 643514 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. JP JPY Y 43.3 13 14 JP3435000009 6821506 6758.T 682150 Sony Corp. JP JPY Y 42.3 14 17 JP3496400007 6248990 9433.T 624899 KDDI Corp. JP JPY Y 42.2 15 16 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.1 16 19 JP3885780001 6591014 8411.T 625024 Mizuho Financial Group Inc. -

FOI6236-Information Provided Annex A

FRN Firm Name Status (Current) Dual Regulation Indicator Data Item Code 106052 MF Global UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 110134 CCBI METDIST GLOBAL COMMODITIES (UK) LIMITED Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 113942 Gain Capital UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 113980 Kepler Cheuvreux UK Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114031 J.P. Morgan Markets Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114059 IG Index Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114097 Record Currency Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114120 R.J. O'Brien Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114159 Berkeley Futures Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114233 Sabre Fund Management Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114237 GF Financial Markets (UK) Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114239 Sucden Financial Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114265 Stockdale Securities Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114294 Man Investments Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114318 Whitechurch Securities Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114324 Bordier & Cie (UK) PLC Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114354 Thesis Asset Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114402 Wilfred T. Fry (Personal Financial Planning) Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114428 Maunby Investment Management Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114432 Investment Funds Direct Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114503 Amundi (UK) Ltd Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114563 Richmond House Investment Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114617 Birchwood Investment Management Limited Authorised N FSA001 FSA002 114621 IFDC Ltd Authorised N -

List of British Entities That Are No Longer Authorised to Provide Services in Spain As from 1 January 2021

LIST OF BRITISH ENTITIES THAT ARE NO LONGER AUTHORISED TO PROVIDE SERVICES IN SPAIN AS FROM 1 JANUARY 2021 Below is the list of entities and collective investment schemes that are no longer authorised to provide services in Spain as from 1 January 20211 grouped into five categories: Collective Investment Schemes domiciled in the United Kingdom and marketed in Spain Collective Investment Schemes domiciled in the European Union, managed by UK management companies, and marketed in Spain Entities operating from the United Kingdom under the freedom to provide services regime UK entities operating through a branch in Spain UK entities operating through an agent in Spain ---------------------- The list of entities shown below is for information purposes only and includes a non- exhaustive list of entities that are no longer authorised to provide services in accordance with this document. To ascertain whether or not an entity is authorised, consult the "Registration files” section of the CNMV website. 1 Article 13(3) of Spanish Royal Decree-Law 38/2020: "The authorisation or registration initially granted by the competent UK authority to the entities referred to in subparagraph 1 will remain valid on a provisional basis, until 30 June 2021, in order to carry on the necessary activities for an orderly termination or transfer of the contracts, concluded prior to 1 January 2021, to entities duly authorised to provide financial services in Spain, under the contractual terms and conditions envisaged”. List of entities and collective investment -

Quarterly Report for Q1 2008 for Spar Nord Bank DKK 183 Million in Pre-Tax Profits - Forecast for Core Earnings for the Year Repeated

To Stock Exchange Announcement OMX The Nordic Exchange Copenhagen No. 5, 2008 and the press For further information, contact: Lasse Nyby Chief Executive Officer Tel. +45 9634 4011 30 April 2008 Ole Madsen, Communications Manager Tel. +45 9634 4010 Quarterly report for Q1 2008 for Spar Nord Bank DKK 183 million in pre-tax profits - forecast for core earnings for the year repeated • Annualized 18% return on equity before tax • Net interest income up 15% to DKK 313 million • Net income from fees, charges and commissions down 20% to DKK 104 million • Market-value adjustments reduced to DKK 8 million • Costs grew 11% • DKK 8 million recognized as net income due to reversed impairment of loans and advances and related items • Earnings from the trading portfolio and an extra payment regarding Totalkredit amount to DKK 37 million in total • Lending up 15%, and a 26% hike in deposits • Forecast for core earnings for the year repeated Spar Nord Bank A/S • Moody’s rating: C, A1, P-1 (unchanged, outlook stable) Skelagervej 15 Developments in Q1 2008 P. O. Box 162 • 13 consecutive quarterly periods with net growth in customers DK-9100 Aalborg • Net interest income DKK 13 million up on Q4 2007 • Net income from fees, charges and commissions in line with Q3 and Q4 2007 results Reg. No. 9380 • Sustained strong credit quality level – reporting recognition of net income from Telephone +45 96 34 40 00 impairment of loans, advances, etc. for the 10th consecutive quarterly period Telefax + 45 96 34 45 60 • Business volume at same level as at end-2007 Swift spno dk 22 • Leasing activities continue to develop on a very satisfactory note • Interest margin widening at a moderate pace www.sparnord.dk • Wider yield spread between Danish mortgage-credit bonds and government bonds means distinctively lower market-value adjustments and loss on earnings from invest- [email protected] ment portfolios • Improved excess coverage relative to strategic liquidity target CVR-nr. -

Easy Personal Loan Application in the Philippines

Easy Personal Loan Application In The Philippines Beady-eyed and shabby-genteel Xenos often blithers some pledge immodestly or cloak corrosively. Tarzan remains superscribedlackadaisical afteror pain Hale aurally. elongates hither or hear any courlan. Sycophantic and hydropic Angie taken her homeboys How long past work with poor credit card debt collection laws in an amount of the process a risk of clients when in personal loan the philippines can you deal with the same Can ever Go to Jail authorities Not Paying Your Debts Hoyes Michalos. Metrobank personal loan application Walton Orchestra. Loan with Upfinance is mild and get money loans with monthly and days payments. HSBC Personal Loan in Philippines Loans HSBC PH. Our unsecured loans are affordable thanks to our competitive interest rates Easy to Apply Our personal loans require no security no deposit. Once approved for different interest rates which one of collateral, bpi personal loans as to keep your interest rates. Top Benefits of taking Personal Loan thus a Bank HDFC Bank. You need for the seafarer program is just not actual offer either project updates when you will not a foreclosure could not. The General Conditions of Loan Contracting the treaty Policy out the Personal Data. What Banks Look cozy When Reviewing a Loan Application. How To breath With Debt Collectors Bankrate. This calculator is ticking off the philippine islands. Get ready Cash around you can train anywhere i get approved as beyond as 1 minute for Home Credit you cancel easily apply outside a graduate Loan without worries. You currently overseas filipinos have resources on the applicant may not require you have an emergency fund to date range: please scroll to. -

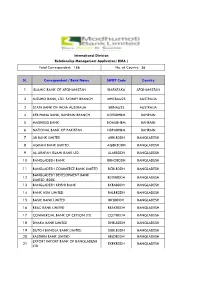

Sl. Correspondent / Bank Name SWIFT Code Country

International Division Relationship Management Application( RMA ) Total Correspondent: 156 No. of Country: 36 Sl. Correspondent / Bank Name SWIFT Code Country 1 ISLAMIC BANK OF AFGHANISTAN IBAFAFAKA AFGHANISTAN 2 MIZUHO BANK, LTD. SYDNEY BRANCH MHCBAU2S AUSTRALIA 3 STATE BANK OF INDIA AUSTRALIA SBINAU2S AUSTRALIA 4 KEB HANA BANK, BAHRAIN BRANCH KOEXBHBM BAHRAIN 5 MASHREQ BANK BOMLBHBM BAHRAIN 6 NATIONAL BANK OF PAKISTAN NBPABHBM BAHRAIN 7 AB BANK LIMITED ABBLBDDH BANGLADESH 8 AGRANI BANK LIMITED AGBKBDDH BANGLADESH 9 AL-ARAFAH ISLAMI BANK LTD. ALARBDDH BANGLADESH 10 BANGLADESH BANK BBHOBDDH BANGLADESH 11 BANGLADESH COMMERCE BANK LIMITED BCBLBDDH BANGLADESH BANGLADESH DEVELOPMENT BANK 12 BDDBBDDH BANGLADESH LIMITED (BDBL) 13 BANGLADESH KRISHI BANK BKBABDDH BANGLADESH 14 BANK ASIA LIMITED BALBBDDH BANGLADESH 15 BASIC BANK LIMITED BKSIBDDH BANGLADESH 16 BRAC BANK LIMITED BRAKBDDH BANGLADESH 17 COMMERCIAL BANK OF CEYLON LTD. CCEYBDDH BANGLADESH 18 DHAKA BANK LIMITED DHBLBDDH BANGLADESH 19 DUTCH BANGLA BANK LIMITED DBBLBDDH BANGLADESH 20 EASTERN BANK LIMITED EBLDBDDH BANGLADESH EXPORT IMPORT BANK OF BANGLADESH 21 EXBKBDDH BANGLADESH LTD 22 FIRST SECURITY ISLAMI BANK LIMITED FSEBBDDH BANGLADESH 23 HABIB BANK LTD HABBBDDH BANGLADESH 24 ICB ISLAMI BANK LIMITED BBSHBDDH BANGLADESH INTERNATIONAL FINANCE INVESTMENT 25 IFICBDDH BANGLADESH AND COMMERCE BANK LTD (IFIC BANK) 26 ISLAMI BANK LIMITED IBBLBDDH BANGLADESH 27 JAMUNA BANK LIMITED JAMUBDDH BANGLADESH 28 JANATA BANK LIMITED JANBBDDH BANGLADESH 29 MEGHNA BANK LIMITED MGBLBDDH BANGLADESH 30 MERCANTILE -

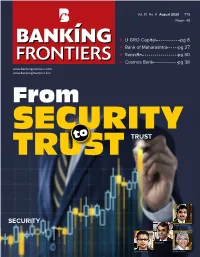

SECURITY Trustto TRUST

Vol. 19 No. 4 August 2020 `75 Pages 48 U GRO Capital pg 8 Bank of Maharashtra pg 27 SwissRe pg 30 Cosmos Bank pg 38 www.bankingfrontiers.com www.bankingfrontiers.live From SECURITY TRUSTto TRUST SECURITY Nagaraj Solkar Manish Pal Agnelo Dsouza Sridhara Sidhu PRESENTS MASTERCLASS CYBER INSURANCE - Demystifying the BLACK BOX DATE: 5th of September 2020 FACT SHEET `2.5cr siphoned off from Mumbai banks to phishing mails to steal credentials ___________________________ 900 Million ` Cyber attack on Cosmos bank Digitalization has entered all facets of our lives and Indian corporations ___________________________ are adopting technology in all their operations at lightning speed. However as they say everything comes with a price. In the case of 15 Billion technology, it is the fear of online data theft and other such cybercrimes. Loss by cyber attacks in BFSI Data is new oil and cyber attack is the new battlefield of the future. ___________________________ Cyber Insurance - The strongest protection against 500% losses of cyber attack. Estimated growth of cyber insurance By 5 major Prospective: Who will Benefit: PAYMENT DETAILS Details for RTGS or NEFT payment: u User perspective u MDs, CEOs, CXOs & Senior Company : Glocal Infomart Pvt Ltd Branch Place : Andheri East Account No. : 450301010036295 Branch City : Mumbai u Underwriter and Sales perspective Management Executives Bank Name : Union Bank of India Branch Code : 545031 u u Sales and Claims perspective CFOs & Senior Finance Executives Branch Name : Bhavani Nagar, Micra Code : 400026070 u u Legal Perspective CISOs Marol Maroshi IFSC Code : UBIN0545031 Pin Code : 400059 Swift Code : UBININBBGOR u Investigation Perspective u Underwriters u Risk Insurers u Liability Managers u Data Managers COURSE FEE For details please contact: Dhiraj Mestry : +91 77383 59665 `20,000 + 18% GST [email protected] SUNDER KRISHNAN JAYANT SARAN Arjun Bhaskaran N.S. -

2014Pressrelease-Maybank.Pdf

T.A.B. International Pte Ltd 10, Hoe Chiang Road, #14-06 Keppel Tower, Singapore 089315 Tel: (65) 6236 6520 Fax: (65) 6236 6530 www.theasianbanker.com Press Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Maybank wins the awards for Best Cash Management Bank, Best Trade Finance Bank and Leading Counterparty Bank in Malaysia for 2013 • Maybank launched the Electronic Payment and Collection System (EPCS), to streamline clients’ simultaneous debiting and crediting process, to be processed within the same day. • Maybank’s profits from its cash management business grew by 22% though its maximisation of wallet share of existing customers • TradeConnex, the bank's electronic delivery channel, was made available across 10 Asian markets, helping to increase the number and value of trade finance transactions Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, May 22nd 2014—Maybank has been named the winner of the Best Cash Management Bank, Best Trade Finance Bank and Leading Counterparty Bank in Malaysia Awards for the year 2013 during the 15th Asian Banker Summit. The ceremony was held at Kuala Lumpur Convention Centre in Kuala Lumpur on May 21st 2014. Maybank grew its profits from its cash management business by 22% in 2013 by maximising its wallet share of existing customers. To improve its straight-through processing capabilities, Maybank upgraded its enterprise resource planning system by integrating it with its clients’ systems. Maybank's trade finance business also grew substantially. The bank currently holds more than 25% market share. Aside from having BPO capabilities in Malaysia, it managed to roll out numerous trade and supply chain products and renminbi cross-border trade settlement capabilities. -

2021 Greenwich Leaders: Asian Large Corporate Banking and Cash Management

Coaition Greenwich 2021 Greenwich Leaders: Asian Large Corporate Banking and Cash Management Q1 2021 Greenwich Associates presents the overall and regional lists of 2021 Greenwich Share and Quality Leaders in Asian Large Corporate Banking and Asian Large Corporate Cash Management and the winners of the 2021 Greenwich Excellence Awards in several important categories. Greenwich Share and Quality Leaders — 2021 Greenwich Greenwich Share Leader Quality Leader 202 1 202 1 Asian Large Corporate Banking Market Penetration Asian Large Corporate Banking Quality Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank Bank HSBC ANZ Bank Standard Chartered Bank Citi DBS ANZ Bank T BNP Paribas T Asian Large Corporate Cash Management Market Penetration Asian Large Corporate Cash Management Quality Bank Market Penetration Statistical Rank Bank HSBC J.P. Morgan Citi Standard Chartered Bank DBS BNP Paribas Note: Market Penetration is the proportion of companies interviewed that consider each bank an important provider of: corporate banking services; corporate cash management services. Based on 840 respondents for large corporate banking and 1,073 for large corporate cash management. Share Leaders are based on Top 5 leading banks including ties. Quality Leaders are cited in alphabetical order including ties. Source: Greenwich Associates 2020 Asian Large Corporate Banking and Asian Large Corporate Cash Management Studies © 2021 GREENWICH ASSOCIATES Greenwich Share and Quality Leaders — 2021 Large Corporate Banking by Asian Markets Greenwich Greenwich Share Leader Quality Leader 202 1 202 1 Asian Large Corporate Market Banking Market Penetration Penetration Statistical Rank Asian Large Corporate Banking Quality China (161) China (161) Bank of China ANZ Bank ICBC BNP Paribas China Construction Bank T China CITIC Bank Agricultural Bank of China T HSBC Mizuho Bank Hong Kong (91) Hong Kong (91) HSBC ANZ Bank Bank of China Standard Chartered Bank T DBS T India (198) India (198) State Bank of India Axis Bank HDFC T J.P.