A Theory of Informational Autocracy∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheet1 Page 1

Sheet1 № SR MHz програма № SR MHz програма 1 6900 386 BNT 1 101 6900 338 Planeta HD 2 BTV 102 Tiankov HD 3 Nova TV 103 Travel HD 4 TV7 104 Tiankov Music HD 5 BTV Action 105 6900 346 Discovery Science 6 BTV Cinema 106 Discovery World 7 BTV Comedy 107 Hystory HD 8 BTV Lady 108 Das Erste HD 9 6900 394 Diema 109 ZDF HD 10 Kino Nova 110 6900 370 TV Tуризъм 11 Diema Family 111 ARTE HD 12 BNT World 112 ASTRA 3D 13 BNT 2 113 SCT HD 14 TV Evropa 114 SCT HQ 15 SKAT 115 SCT Redlight 16 News 7 116 SCT Exotica 17 Kanal 3 117 SCT Premium 18 6900 402 CNN 118 6900 378 National Geographic 19 Euronews 119 DW 20 BG on Air 120 Al Jazeera 21 VTV 121 CCTV News 22 EBF Business 122 Arte 23 AXN 123 TVE 24 AXN Black 124 TV Polonia 25 AXN White 125 BNT HD 26 Fox Life 126 5156 298 RTL 27 Fox 127 RTL 2 28 6900 410 History channel 128 SUPER RTL 29 Viasat History 129 n-TV 30 Viasat Explorer 130 VOX 31 Viasat Nature 131 RTL NITRO 32 TV 1000 132 4583 162 RAI 1 33 Nat Geo Wild 133 RAI 2 34 Discovery channel 134 RAI 3 35 Animal Planet 135 RAI NEWS 36 BOX HD 136 6250 154 TRT 1 37 6900 434 MGM 137 TRT HABER 38 Moviestar 138 TRT TURK 39 DaVinci Learning 139 TRT MUZIK 40 Super 7 140 TRT COCUK 41 Disney channel 141 TRT AVAZ 42 Disney Junior 142 EURONEWS 43 Cartoon Network 143 TRT ARAPCA 44 TLC 144 TRT SPOR 45 24 Kitchen 145 TRT 6 46 Fiesta 146 TRT DIYANET(Anadolu) 47 Travel Channel 147 5625 146 OTV Valentino 48 6900 442 CLASSICA HD 148 Duga + 49 VH 1 149 K CN 3 50 MTV 150 Canal M 51 MTV Rock 151 MKTV 2 SAT 52 The Voice 152 KCN 1 Page 1 Sheet1 53 City TV 153 Posavina TV 54 Box TV 154 SVET + 55 Planeta Folk 155 DUNA World 56 Folklor TV 156 Yu Planet test 57 Fan TV 157 K CN Music 2 58 Planeta TV 158 Eurochannel 59 6900 450 Balkanika Music 5156 138 60 бр. -

Bulgaria AMMIE Volume Report Track Changes V3

Report on youth exposure to alcohol commercials on television in Europe: rt on youth exposure to alcohol commercials on television Volume of youth exposure in Bulgaria Results of monitoring televised alcohol commercials in Bulgaria in 2010 1 Report on youth exposure to alcohol commercials on television in Europe: Volume of youth exposure in Bulgaria Results of monitoring televised alcohol commercials in Bulgaria in 2010 Author: Daniela Alexieva Foundation ‘Horizonti 21’ Sofia ‘Bolgrad’ Str. 5 Phone: +359(02)963 32 80 Fax: +359(02)963 32 80 Email: [email protected] Editing and contact person: Avalon de Bruijn ( [email protected] ) European Centre for Monitoring Alcohol Marketing (EUCAM) Utrecht, the Netherlands, November 2011 Conducted as part of the Alcohol Marketing Monitoring in Europe (AMMIE) project. AMMIE is coordinated by the Dutch Institute for Alcohol Policy (STAP). Contact details: Dutch Institute for Alcohol Policy (STAP) Postbus 9769 3506 ET Utrecht +31306565041 [email protected] www.stap.nl This report arises from the project Alcohol Marketing Monitoring in Europe which has received funding from the European Union, in the framework of the Health Program. 2 Index of contents Summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Effects of alcohol advertising ....................................................................................................... -

1-2-3 TV 24 Horas 24 Kitchen 24 Kitchen HD 3Sat 7/8TV

1-2-3 TV 24 Horas 24 kitchen 24 kitchen HD 3sat 7/8TV Al Jazeera 7/8TV HD Agro TV Alfa TV Animal Planet Animal Planet HD Balkans HD Auto Motor ARD “Das Erste” ARTE GEIE Auto Motor Sport AXN AXN Black Sport HD AXN White B1B Action B1B Action HD BabyTv Balkanika Music Balkanika Music HD Bloomberg TV BG Music BG Music HD Black Diamondz HD BNT 1 BNT 1 -1ч Bulgaria BNT 1 -2ч. BNT 1 HD BNT 2 BNT 2 HD BNT 3 HD BNT 4 BNT 4 HD Bober TV Box TV BSTV BSTV HD bTV bTV -1ч. bTV -2ч. bTV Action bTV Action HD bTV Cinema bTV Cinema HD bTV Comedy bTV Comedy HD bTV HD bTV Lady bTV Lady HD Bulgare ` Bulgare HD Bulgaria On Air CCTV-4 CGTN CGTN - Español CGTN - Français CGTN – Documentary Chasse & Peche Chillayo Cinemania العرب - CGTN - Русский CGTN Cinemania HD City TV Classical Harmony HD Code Fashion TV HD Code Health Code Health HD Cubayo HD Detskiy Mir Diema Diema Family Diema Sport Diema Sport 2 Diema Sport 2 HD Diema Sport HD Discovery HD Discovery Science Discovery Science HD Discovery SD Disney Channel Disney Junior DM SAT Dom Kino Dom Kino Premium DSTV ECTV ECTV for kids HD EDGE Sport ekids English Club HD Epic Drama ERT World Eurosport Eurosport 2 Eurosport 2 HD Eurosport HD Evrokom Evrokom HD FEN Folk FEN Folk HD FEN TV FEN TV HD Flame HD Folklor TV Folklor TV HD Folx TV Food Netwоrk Food Netwоrk HD Fox Fox Crime Fox Crime HD Fox HD Fox Life Fox Life HD France 2 HD France 3 HD France 4 HD France 5 HD Galaxy HD Health & Wellness HD Hit Mix HD Homey's HD HRT 4 HD HRT INT ID Xtra ID Xtra HD Insight HD Kabel 1 (Kabel eins) Kabel Eins Doku Kanal 4 Kanal 4 HD Karusel KCN KCN 2 Music KCN 3 Svet plus KiKa KiKa HD Kino Nova Lolly Kids HD Luxe and Life HD M2 HD Magic TV MAX Sport 1 MAX Sport 1 HD MAX Sport 2 MAX Sport 2 HD MAX Sport 3 MAX Sport 3 HD MAX Sport 4 MAX Sport 4 HD Moviestar Moviestar HD MTV Hits Muzika N24 (WELT) N24 DOKU (WELT) Nache Lubimoe Kino National Geo National National Geo Wild National Geographic Chaneel Nick Jr Wild HD Geographic HD Nickelodeon Nova Nova -1ч. -

Evaluation of the Public Service : Broadcasting in Bulgaria

Evaluation of the public service : broadcasting in Bulgaria Autor(en): Baeva, Gergana Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Studies in Communication Sciences : journal of the Swiss Association of Communication and Media Research Band (Jahr): 8 (2008) Heft 2-3 PDF erstellt am: 07.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-791021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch General Section Studies in Communication Sciences 8/2&3 (2008) 95-116 Gergana Baeva* EVALUATION OF THE PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING IN BULGARIA Democratic consolidation of the new Eastern European member states has been controversial among political scientists. This article proposes to use the media, m particular Public Service Broadcasting (PSB), as an indicator of successful consolidation. -

Institut Für Rundfunkökonomie an Der Universität Zu Köln

f Institut für Rundfunkökonomie an der Universität zu Köln Aleksandar Todorov The Broadcasting System in Bulgaria at the End of the Analogue Age. An Economic Perspective Working Papers of the Institute for Broadcasting Economics at the University of Cologne No. 261 Cologne, in January 2010 Arbeitspapiere des Instituts für Rundfunkökonomie Working Papers of the Institute for Broadcasting Economics ISSN der Arbeitspapiere: 0945-8999 ISSN of the Working Papers: 0945-8999 ISBN des vorliegenden Arbeitspapiers 261: 978-3-938933-65-7 ISBN of the Working Paper at hand: 978-3-938933-65-7 Schutzgebühr 21,-- € Price 21,-- € Die Arbeitspapiere können im Internet eingesehen und abgerufen werden unter der Adresse http://www.rundfunk-institut.uni-koeln.de The Working Papers can be read and downloaded from the Internet URL http://www.rundfunk-institut.uni-koeln.de Mitteilungen und Bestellungen richten Sie bitte per E-Mail an: [email protected] oder an die unten genannte Postanschrift Messages and Orders to the Institute can be sent via Email to: [email protected] or to the mailing address below. Institut für Rundfunkökonomie an der Universität zu Köln Hohenstaufenring 57a 50674 Köln Telefon: (0221) 23 35 36 Telefax: (0221) 24 11 34 Aleksandar Todorov The Broadcasting System in Bulgaria at the End of the Analogue Age. An Economic Perspective List of Figures......................................................................................................5 List of Tables.......................................................................................................6 -

Title Slide for Mediaplus

MEDIA LANDSCAPE BULGARIA 2017 Introduction to Media Overview The analyses and trends outlined in this media overview present Media Club’s reading of all available data and are largely based on the agency’s experience as a direct media buyer, our know-how, and our perception of the current frame of mind of both clients and media. Despite the overall confusion stemming from the various data sources, several trends are confirmed by both gross and net data: The media Ad market shows stable growth, with ad investments shifting to channels that provide for effective and efficient media campaigns that can be measured and evaluated. Media consolidation facilitates multi-channel deals and execution of cross-platform campaigns that tackle the changing pattern of media consumption. The following pages aim at providing businesses with a glimpse of what we do and a snapshot of the media landscape we all navigate through. We hope you enjoy reading it. Source: Media Club Strategic Insights 2017, Bulgaria CONTENT 1. General Information ▪ Key Facts ▪ Advertising Investments ▪ Media Usage 2. TV 3. Online 4. Radio 5. Print 6. Cinema KEY FACTS Sociodemographic & Economic Facts Gross Domestic Product Population Age Structure absolute and in % Total per capita €48 128 mln. € 6 777 2016 2016 Under 15 15-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75 + 1001 K 660 K 947 K 1 056 K 983 K 982 K 861 K 611 K 14% 9% 13% 15% 14% 14% 12% 9% Comparative Population Gross Value Added by Economic Sector Consumer Private Household Spending by Sector in million population in million € in % Foods and non-alcoholic beverages Germany 82 Arts entertainment and recreation… 945 England 66 Others (incl. -

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 24.9.2012 SWD(2012) 269 Final

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 24.9.2012 SWD(2012) 269 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT PROMOTION OF EUROPEAN WORKS IN EU SCHEDULED AND ON-DEMAND AUDIOVISUAL MEDIA SERVICES PART III ANNEX to PART II on the application of Articles 16 and 17 of Directive 2010/13/EU for the period 2009-2010 Accompanying the document First Report on the Application of Articles 13, 16 and 17 of Directive 2010/13/EU for the period 2009-2010 {COM(2012) 522 final} EN EN TABLE OF CONTENTS ANNEX 1: .............................................................................................................................. 3 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS.......................................................................................... 3 ANNEX 2: .............................................................................................................................. 6 CHARTS AND TABLES ON THE APPLICATION OF ARTICLES 16 AND 17 ................ 6 ANNEX 3: ............................................................................................................................ 12 LIST OF TELEVISION CHANNELS IN THE MEMBER STATES WHICH FAILED TO ACHIEVE THE MAJORITY PROPORTION REQUIRED BY ARTICLE 16 ................... 12 ANNEX 4: ............................................................................................................................ 24 LIST OF TELEVISION CHANNELS IN THE MEMBER STATES WHICH FAILED TO ACHIEVE THE MAJORITY PROPORTION REQUIRED BY ARTICLE 17 ................... 24 2 ANNEX 1: PERFORMANCE INDICATORS The following indicators -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: BULGARIA Mapping Digital Media: Bulgaria

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: BULGARIA Mapping Digital Media: Bulgaria A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Vesislava Antonova and Andrian Georgiev (lead reporters) EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Magda Walter (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 1 March 2013 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 11 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Sheet1 Page 1

Sheet1 № SR MHz програма № SR MHz програма 1 6900 386 BNT 1 103 6900 338 Planeta HD 2 BTV 104 Tiankov HD 3 Nova TV 105 Travel HD 4 TV7 106 Tiankov Music HD 5 BTV Action 107 6900 346 Discovery Science 6 BTV Cinema 108 Discovery World 7 BTV Comedy 109 Hystory HD 8 BTV Lady 110 Das Erste HD 9 6900 394 Diema 111 ZDF HD 10 Kino Nova 112 6900 370 TV Tуризъм 11 Diema Family 113 ARTE HD 12 BNT World 114 ASTRA 3D 13 BNT 2 115 SCT HD 14 TV Evropa 116 SCT HQ 15 SKAT 117 SCT Redlight 16 News 7 118 SCT Exotica 17 Kanal 3 119 SCT Premium 18 6900 402 CNN 120 6900 378 National Geographic 19 Euronews 121 DW 20 BG on Air 122 Al Jazeera 21 VTV 123 CCTV News 22 EBF Business 124 Arte 23 AXN 125 TVE 24 AXN Black 126 TV Polonia 25 AXN White 127 BNT HD 26 Fox Life 128 5156 298 RTL 27 Fox 129 RTL 2 28 6900 410 History channel 130 SUPER RTL 29 Viasat History 131 n-TV 30 132 VOX 31 133 RTL NITRO 32 TV 1000 134 4583 162 RAI 1 33 Nat Geo Wild 135 RAI 2 34 Discovery channel 136 RAI 3 35 Animal Planet 137 RAI NEWS 36 BOX HD 138 6250 154 TRT 1 37 6900 434 MGM 139 TRT HABER 38 Moviestar 140 TRT TURK 39 DaVinci Learning 141 TRT MUZIK 40 Super 7 142 TRT COCUK 41 Disney channel 143 TRT AVAZ 42 Disney Junior 144 EURONEWS 43 Cartoon Network 145 TRT ARAPCA 44 TLC 146 TRT SPOR 45 24 Kitchen 147 TRT 6 46 Fiesta 148 TRT DIYANET(Anadolu) 47 ekids 48 Travel Channel 149 5625 146 OTV Valentino 49 6900 442 CLASSICA HD 150 Duga + 50 VH 1 151 K CN 3 51 MTV 152 Canal M 52 MTV Rock 153 MKTV 2 SAT Page 1 Sheet1 53 The Voice 154 KCN 1 54 City TV 155 Posavina TV 55 Box TV 156 SVET + 56 Planeta Folk 157 DUNA World 57 Folklor TV 158 Yu Planet test 58 Fan TV 159 K CN Music 2 59 Planeta TV 160 Eurochannel 60 6900 450 Balkanika Music 161 5156 138 60 бр. -

Publicis Media Presentation Template

TV & DIGITAL REPORT JANUARY 2021 TV REPORT FOCUSED ON NOVA NEWS Source: GARB and Nielsen Admosphere Data: People meter, national base TG: A 18-49 Currency: BGN gross 30 Base Diff 2020 2021 Lockdown 25 SLIGHTLY 20,4 20 21,5 HIGHER T V 20,8 21,1 19,5 19,0 19,4 AUDIENCE ON 17,9 17,1 15 16,5 Y TD BASE 15,6 15,5 16,0 Jan 2021 registered 5% higher TV viewership than 10 Jan 2020. 5 - jan feb mar apr may jun jul aug sept oct nov dec GARB, 18-49 2 Live TV 9 10 8 8 9 9 6 5 20 22 9 11 8 26 27 Other 10 Other 29 29 9 8 NBG INCREASED 8 8 DISCOVERY 7 8 TSH SHARE ON THE BTV ACTION ACCOUNT OF BNT DIEMA FAMILY 32 35 30 30 28 32 BMG DIEMA BMG 8 8 On channel basis Nova & 7 BTV CINEMA 7 7 NBG 8 bTV declined slightly in all BTV COMEDY time slots, Nova remained 23 22 21 KINO NOVA 19 19 rather stable. 18 Kino Nova was the top niche BNT 1 43 45 44 46 43 45 channel as usual. BTV 26 NOVA TV 25 24 26 25 24 Dec Jan Dec Jan Dec Jan Dec Jan Dec Jan Dec Jan 06:00-18:59 19:00-23:59 All day 06:00-18:59 19:00-23:59 All day Source: GARB, A18-49 3 Rtg (19:00-22:30) BTV 8,64 16,00 NOVA TV 9,78 NOVE KEPT 13% 14,00 HIGHER 12,00 OVERALL PT AUDIENCE THAN 10,00 BTV IN JANUARY 8,00 bTV outperformed Nova on 6,00 23rd of January with its Saturday movie program. -

Tv Weekly Report Focused on Weekend Pt Programs

TV WEEKLY REPORT FOCUSED ON WEEKEND PT PROGRAMS Source: GARB Data: People meter, national base Period: 24-31.05. TG: A 18-49 Currency: BGN gross DURING THE POST- CRISIS PERIOD NEWS W E B S I T E S SUSTAIN GROWTH OF PAGE VIEWS, WHILE I N T O TA L T H E Y ARE DECREASING BY 5 % 14 All sites News sites 13 Mar All sites News sites +286 +337 +255 +206 May - - 13 K users K users K users K users 31 Real users Real Peak of the crisis Peak May May 2020 vs the same period 2019 May May 2020 vs the same period 2019 New New Normal Post crisis Post Lockdown +15% +78% -5% +28% Page views +8pp +10pp +6pp +6pp Reach Source: Gemius, A18-49 1 Reach Time spent PUT +31% +0:55 +6 hour DURING THE CRISIS CONTINUED TO NORMALIZE DURING pp May 2020 vs the same period 2019 period same the vs 2020 May 13 - Mar 13 Peak of the crisis the of Peak THE HIGH INCREASE IN TV VIEWERSHIP Lockdown 06 – 07 0% 06 – 07 0% 07 – 08 10% 07 – 08 11% T H E P O S T 08 – 09 33% 08 – 09 37% 09 – 10 40% PUT evolution in postPUT 09 – 10 43% 10 – 11 35% evolution during PUT the crisis 10 – 11 49% 11 – 12 31% 11 – 12 58% Source: GARB, GARB, A18 Source: 12 – 13 30% 12 – 13 58% 13 – 14 34% 13 – 14 60% - CRISIS PERIOD 14 – 15 30% 14 – 15 55% 15 – 16 38% 15 – 16 46% - 16 – 17 36% 49 - 16 – 17 42% crisistime 17 – 18 20% 17 – 18 29% 18 – 19 17% 18 – 19 26% 19 – 20 6% 19 – 20 18% 20 – 21 8% 20 – 21 21% 21 – 22 6% 21 – 22 20% 22 – 23 5% 22 – 23 18% 23 – 00 10% 23 – 00 20% +17% +0:29 +2 hour pp 31 May 2020 vs the same period 2019 period same the vs 2020 May 31 - May 14 Post crisis Post 2 New Normal New WEEKLY VIEWERSHIP INCREASED SLIGHTLY. -

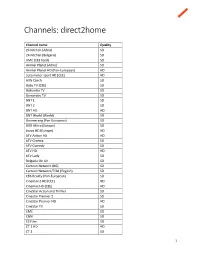

Channels: Direct2home

Channels: direct2home Channel name Quality 24 Kitchen (Adria) SD 24 Kitchen (Bulgaria) SD AMC (CEE feed) SD Animal Planet (Adria) SD Animal Planet HD (Pan-European) HD auto motor sport HD (CEE) HD AXN Czech SD Baby TV (CEE) SD Balkanika TV SD Barrandov TV SD BNT 1 SD BNT 2 SD BNT HD HD BNT World (World) SD Boomerang (Pan-European) SD BOX Africa (Europe) SD brava HD (Europe) HD bTV Action HD HD bTV Cinema SD bTV Comedy SD bTV HD HD bTV Lady SD Bulgaria On Air SD Cartoon Network (BG) SD Cartoon Network/TCM (English) SD CBS Reality (Pan-European) SD Cinemax 2 HD (CEE) HD Cinemax HD (CEE) HD CineStar Action and Thriller SD Cinestar Premier 2 SD CineStar Premier HD HD CineStar TV SD CMC SD CNN SD CS Film SD ČT 1 HD HD ČT 2 SD 1 ČT 24 SD ČT Art/Detem SD ČT Sport HD HD DAJTO HD HD Diema SD Diema Family SD Diema Sport 2 HD HD Diema Sport HD HD Discovery Channel (Adria feed) SD Discovery Channel (BG feed) SD Discovery Channel (CZ) SD Discovery Science (Europe) SD Discovery Science HD (Europe) HD Discovery Showcase HD (Europe) HD Discovery World (Europe) SD Disney Channel (Adria) SD Disney Channel (CZ) SD DJAZZ HD (Europe) HD DocuBox HD (Europe) HD Doma (SK) SD Doma TV (Croatia) SD Duck TV SD Dusk International SD E! Entertainment SD EROX SD EROXXX HD HD Eurosport SD Eurosport 2 (with Bundesliga) SD Eurosport 2 HD (with Bundesliga) HD Eurosport HD HD FANDA SD Fast&Fun Box HD HD Federalna TV SD Fen TV SD Fight Box HD HD Fight Channel (Adria) SD Fight World HD HD Film + SD Film Box HD (Balkans) HD Film Box HD CZ HD Film Box Plus CZ SD 2 Film BOX