Within the Pages of the Black Book of Carmarthen (National Library Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, the Hanesyn Hên

04 Guy_Studia Celtica 50 06/12/2016 09:34 Page 69 STUDIA CELTICA, L (2016), 69 –105, 10.16922/SC.50.4 A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, The Hanesyn Hên BEN GUY Cambridge University In 1658, William Maurice made a catalogue of the most important manuscripts in the library of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt, in which 158 items were listed. 1 Many copies of Maurice’s catalogue exist, deriving from two variant versions, best represented respec - tively by the copies in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales [= NLW], Wynnstay 10, written by Maurice’s amanuenses in 1671 and annotated by Maurice himself, and in NLW Peniarth 119, written by Edward Lhwyd and his collaborators around 1700. 2 In 1843, Aneirin Owen created a list of those manuscripts in Maurice’s catalogue which he was able to find still present in the Hengwrt (later Peniarth) collection. 3 W. W. E. Wynne later responded by publishing a list, based on Maurice’s catalogue, of the manuscripts which Owen believed to be missing, some of which Wynne was able to identify as extant. 4 Among the manuscripts remaining unidentified was item 33, the manuscript which Edward Lhwyd had called the ‘ Hanesyn Hên ’. 5 The contents list provided by Maurice in his catalogue shows that this manuscript was of considerable interest. 6 The entries for Hengwrt 33 in both Wynnstay 10 and Peniarth 119 are identical in all significant respects. These lists are supplemented by a briefer list compiled by Lhwyd and included elsewhere in Peniarth 119 as part of a document entitled ‘A Catalogue of some MSS. -

Vebraalto.Com

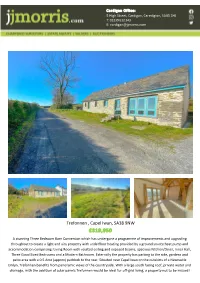

Cardigan Office: 5 High Street, Cardigan, Ceredigion, SA43 1HJ T: 01239 612 343 E: [email protected] Trefonnen , Capel Iwan, SA38 9NW £319,950 A stunning Three Bedroom Barn Conversion which has undergone a programme of improvements and upgrading throughout to create a light and airy property with underfloor heating provided by a ground source heat pump and accommodation comprising: Living Room with vaulted ceiling and exposed beams, spacious Kitchen/Diner, Inner Hall, Three Good Sized Bedrooms and a Modern Bathroom. Externally the property has parking to the side, gardens and patio area with a 0.5 Acre (approx) paddock to the rear. Situated near Capel Iwan on the outskirts of a Newcastle Emlyn, Trefonnen benefits from panoramic views of the countryside. With a large south facing roof, private water and drainage, with the addition of solar panels Trefonnen would be ideal for off‐grid living, a property not to be missed! Situation Bedroom 3 7'9" x 6'11" (2.37 x 2.12) Set some 2.5 miles from the rural village of Capel Iwan and 3.0 miles away from the market town of Newcastle Emlyn, with Carmarthen only 15.5 miles away. Newcastle Emlyn is a quaint market town dating back to the 13th Century. Straddling the two counties of Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire, Newcastle Emlyn town lies in Carmarthenshire and Adpar on the outskirts lies in Ceredigion divided by the River Teifi. The town offers residents and tourists a range of amenities include a Castle, supermarkets, restaurants and coffee shops, Post Office, a primary and secondary school, swimming pool, health centre, leisure centre, theatre, several public houses and many independent shops. -

WHITLAND WARD: ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE Policy Research and Information Section, Carmarthenshire County Council, May 2021

WHITLAND WARD: ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE Policy Research and Information Section, Carmarthenshire County Council, May 2021 Councillors (Electoral Vote 2017): Sue Allen (Independent). Turnout = 49.05% Electorate (April 2021): 1,849 Population: 2,406 (2019 Mid Year Population Estimates, ONS) Welsh Assembly and UK Parliamentary Constituency: Carmarthenshire West & Pembrokeshire © Hawlfraint y Goron a hawliau cronfa ddata 2017 Arolwg Ordnans 100023377 © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023377 Location: Approximately 23km from Carmarthen Town Area: 22.34km2 Population Density: 108 people per km2 Population Change: 2011-2019: +134 (+5.9%) POPULATION STATISTICS 2019 Mid Year Population Estimates Age Whitland Whitland Carmarthenshire Structure Population % % Aged: 0-4 101 4.2 5.0 5-14 267 11.1 11.5 15-24 248 10.3 10.2 25-44 523 21.7 21.6 45-64 693 28.8 28.0 65-74 263 10.9 11.9 75+ 311 12.9 11.9 Total 2,406 100 100 Source: aggregated lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Small Area Population Estimates, 2019, Office for National Statistics (ONS) 16th lowest ward population in Carmarthenshire, and 26th lowest population density. Highest proportion of people over 45. Lower proportion of people with limiting long term illness. Lower proportion of Welsh Speakers than the Carmarthenshire average. 2011 Census Data Population: Key Facts Whitland Whitland % Carmarthenshire People: born in Wales 1585 69.8 76.0 born outside UK 69 3.1 4.1 in non-white ethnic groups 40 1.8 1.9 with limiting long-term illness 474 20.8 25.4 with no -

Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire

OCTOBER 2019 Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire Appendix A Literature Review Final Issue A Two County Economic Study for Carmarthenshire and Pembrokeshire Appendix A Literature Review Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Overview 1 2 National Objectives 2 2.1 Overview 2 2.2 National Development Framework (2019) 2 2.3 Taking Wales Forward (2016-2021) 3 2.4 Prosperity for All: The National Strategy and its Economic Action Plan (2017) 4 2.5 Planning Policy Wales, Edition 10 (2018) 6 3 Regional Objectives 8 3.1 Overview 8 3.2 Enterprise Zones: Haven Waterway 8 3.3 Swansea Bay City Deal 10 3.4 Adjacent to the Larger than Local Area 13 4 Local Context 15 4.1 Overview 15 4.2 Pembrokeshire Local Development Plan 15 4.3 Carmarthenshire Local Development Plan 23 4.4 Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority Local Development Plan 30 4.5 Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 32 4.6 Brecon Beacons National Park LDP2 33 4.7 Conclusions 34 5 Other Relevant Strategy Documents 36 5.1 Overview 36 5.2 Other Relevant National Strategy Documents 36 5.3 Other Relevant CCC documents 36 5.4 Other Relevant Pembrokeshire Documents 37 5.5 Other Relevant Initiatives/ Sources of Funding 39 6 Implications of the Literature Review 41 6.1 Overview 41 6.2 Key Definitions 41 6.3 Areas for Further Consideration 43 | Issue | 18 October 2019 \\GLOBAL\EUROPE\CARDIFF\JOBS\268000\268379-00\4 INTERNAL PROJECT DATA\4-50 REPORTS\10. FINAL REPORTING\2019.10.24 APPENDIX A FINAL ISSUE DOCUMENT REVIEW.DOCX A Two County Economic -

Invisible Ink: the Recovery and Analysis of a Lost Text from the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1)

Invisible Ink: The Recovery and Analysis of a Lost Text from the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1) Introduction In a previous volume of this journal we surveyed a selection of the images and texts which can be recovered from the pages of the Black Book of Carmarthen (NLW Peniarth MS 1) when the manuscript and high-resolution images of it were subject to a series of digital analyses.1 The present discussion focuses on one page of the manuscript, fol. 40v. Although the space was once filled with text dating to just after the compilation of the Black Book, it was obliterated at some stage in the manuscript’s ‘cleansing’.2 In fact, it is possible that this page was erased more than once, and that the shadow of a large initial B which we initially believed to be the start of a second poem is instead evidence of palimpsesting.3 The particular exuberance of the erasure in the bottom quarter of the page may support this view. As it stands, faint traces of lines of text can be seen on the page in its original, digitised and facsimile forms;4 in fact, of these Gwenogvryn Evans’s facsimile preserves the most detail.5 Minims and the occasional complete letter are discernible, but on the whole the page is illegible. Nevertheless, enough of the text of this page is visible for it to feel tantalizingly recoverable, and the purpose of what follows is first to show what can be recovered using modern techniques 1 Williams, ‘The Black Book of Carmarthen: Minding the Gaps’, National Library of Wales Journal 36 (2017), 357–410. -

The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture

THE ORDER OF BARDS OVATES & DRUIDS MOUNT HAEMUS LECTURE FOR THE YEAR 2012 The Thirteenth Mt Haemus Lecture Magical Transformation in the Book of Taliesin and the Spoils of Annwn by Kristoffer Hughes Abstract The central theme within the OBOD Bardic grade expresses the transformation mystery present in the tale of Gwion Bach, who by degrees of elemental initiations and assimilation becomes he with the radiant brow – Taliesin. A further body of work exists in the form of Peniarth Manuscript Number 2, designated as ‘The Book of Taliesin’, inter-textual references within this material connects it to a vast body of work including the ‘Hanes Taliesin’ (the story of the birth of Taliesin) and the Four Branches of the Mabinogi which gives credence to the premise that magical transformation permeates the British/Welsh mythological sagas. This paper will focus on elements of magical transformation in the Book of Taliesin’s most famed mystical poem, ‘The Preideu Annwfyn (The Spoils of Annwn), and its pertinence to modern Druidic practise, to bridge the gulf between academia and the visionary, and to demonstrate the storehouse of wisdom accessible within the Taliesin material. Introduction It is the intention of this paper to examine the magical transformation properties present in the Book of Taliesin and the Preideu Annwfn. By the term ‘Magical Transformation’ I refer to the preternatural accounts of change initiated by magical means that are present within the Taliesin material and pertinent to modern practise and the assumption of various states of being. The transformative qualities of the Hanes Taliesin material is familiar to students of the OBOD, but I suggest that further material can be utilised to enhance the spiritual connection of the student to the source material of the OBOD and other Druidic systems. -

Y in Medieval Welsh Orthography Sims-Williams, Patrick

Aberystwyth University ‘Dark’ and ‘Clear’ Y in Medieval Welsh Orthography Sims-Williams, Patrick Published in: Transactions of the Philological Society DOI: 10.1111/1467-968X.12205 Publication date: 2021 Citation for published version (APA): Sims-Williams, P. (2021). ‘Dark’ and ‘Clear’ Y in Medieval Welsh Orthography: Caligula versus Teilo. Transactions of the Philological Society, 1191, 9-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-968X.12205 Document License CC BY-NC-ND General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 1191 (2021) 9–47 doi: 10.1111/1467-968X.12205 ‘DARK’ AND ‘CLEAR’ Y IN MEDIEVAL WELSH ORTHOGRAPHY: CALIGULA VERSUS TEILO By PATRICK SIMS-WILLIAMS Aberystwyth University (Submitted: 26 May, 2020; Accepted: 20 January, 2021) ABSTRACT A famous exception to the ‘phonetic spelling system’ of Welsh is the use of <y> for both /ǝ/ and the retracted high vowel /ɨ(:)/. -

Carmarthen Bay, Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire, SA17 5HQ

01554 759655 www.westwalesproperties.co.uk Chalet 131 Carmarthen Bay, Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire, SA17 5HQ • Detached holiday chalet • Open plan lounge/kitchen/diner • Three bedrooms • Shower room WE WOULD LIKE TO POINT OUT THAT OUR PHOTOGRAPHS ARE TAKEN WITH A DIGITAL CAMERA WITH A WIDE ANGLE LENS. These particulars have been prepared in all good faith to give a fair overall view of the property. If there is any point which is of specific importance to you, please • Well‐presented throughout • Jubilee court location check with us first, particularly if travelling some distance to view the property. We would like to point out that the following items are • Ideal holiday home investment • Prime coastal holiday park excluded from the sale of the property: Fitted carpets, curtains and blinds, curtain rods and poles, light fittings, sheds, greenhouses ‐ unless specifically specified in the sales particulars. Nothing in these particulars shall be deemed to be a statement that the property is in good • Ideal for families • EPC RATING F structural condition or otherwise. Services, appliances and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested, and no warranty can therefore be given. Purchasers should satisfy themselves on such matters prior to purchase. Any areas, measurements or distances are given as a guide only and are not precise. Room sizes should not be relied upon for carpets and furnishings. £22,000 22 Murray Street, Llanelli, Dyfed, SA15 1DZ 22 Murray Street, Llanelli, Dyfed, SA15 1DZ EMAIL: [email protected] TELEPHONE: 01554 759655 TELEPHONE: 01554 759655 EMAIL: [email protected] Page 8 Page 1 We Say.. -

Community Support Meal Delivery, Shopping, Medication Collection

Community Support Meal Delivery, Shopping, Medication collection, general support during COVID 19 outbreak PEASE NOTE THE SERVICES THAT HAVE BEEN OFFERED MAY CHANGE TIMES AND OFFERS MAY BE EXTENDED OR DISCONTINUED AS THE SITUATION CHANGES. PLEASE CALL SERVICE DIRECT FOR UP TO DATE INFORMATION. Any changes or new services identified please send to [email protected] AMMAN GWEDRAETH Rwyth Cabs currently operate 20 Licensed Taxis including 1-8 Seaters.There are 10 Drivers who are registered with the Local Authority and who have Full DBS Certification. There is Disability access. The company are based in and operate 15 miles from Pontyates Nr Llanelli SA15 STB. Can assist with collection of goods medical supplies and other, in addition to the conveyance of persons etc this list is not exhaustive. A 24/7 Service can be offered. Any queries please call 01267 468250 07791 085096/07905 462519, Jamie, Tracey, or Martin VERIFIED Watkins Grocery, 10 Heol Y Neuadd, Tumble , 01269 832856, meal delivery and grocery deliveries, Ty Dyffryn delivery every Monday at 2.30pm, Thursday at 3.30pm. VERIFIED The Y Farchnad Fach Ltd, 4 Bethesda Rd, Tumble,Llanelli,Dyfed,SA14 6HY, Tel: 01269 844555, they deliver to quite a large area groceries and fuel (gas and coal) and also do a hot meal delivery service. Shop in Capel Hendre also Please phone for further details. VERIFIED Canolfan Maerdy, New Rd, Tairgwaith, Ammanford SA18 1UP, 01269 826893 Community food Hub and centre, Community Car, Canolfan Maerdy can provide online access for CAB advice and essential services. Open weekdays, The Food Hub is open 10.30 to 3pm and has some still has food available, with further food incoming daily - There is access to computers for those needing to go online - The Community Car is still operating for those that need it. -

Full Property Address Current Rateable Value Company Name

Current Rateable Full Property Address Company Name Value C.R.S. Supermarket, College Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3AB 89000 Cws Ltd Workshop & Stores, Foundry Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 2LS 75000 Messrs T R Jones (Betws) Ltd 23/25, Quay Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3DB 33750 Boots Uk Limited Old Tinplate Works, Pantyffynnon Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, 64000 Messrs Wm Corbett & Co Ltd 77, Rhosmaen Street, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, SA19 6LW 49000 C K`S Supermarket Ltd Warehouse, Station Road, Llandeilo, Carmarthenshire, 32000 Llandeilo Builders Supplies Ltd Golf Club, Glynhir Road, Llandybie, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 2TE 31250 The Secretary Penygroes Concrete Products, Norton Road, Penygroes, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA14 7RU 85500 The Secretary Pant Glas Hall, Llanfynydd, Carmarthen, Carmarthenshire, 75000 The Secretary, Lightcourt Ltd Unit 4, Pantyrodin Industrial Estate, Llandeilo Road, Llandybie, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3JG 35000 The Secretary, Amman Valley Fabrication Ltd Cross Hands Business Park, Cross Hands, Llanelli, Carmarthenshire, SA14 6RB 202000 The Secretary Concrete Works (Rear, ., 23a, Bryncethin Road, Garnant, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 1YP 33000 Amman Concrete Products Ltd 17, Quay Street, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3DB 54000 Peacocks Stores Ltd Pullmaflex Parc Amanwy, New Road, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3ER 152000 The Secretary Units 27 & 28, Capel Hendre Industrial Estate, Capel Hendre, Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, SA18 3SJ 133000 Quinshield -

Community Support Meal Delivery

Community Support Meal Delivery, Shopping, Medication collection, general support during COVID 19 outbreak PEASE NOTE THE SERVICES THAT HAVE BEEN OFFERED MAY CHANGE TIMES AND OFFERS MAY BE EXTENDED OR DISCONTINUED AS THE SITUATION CHANGES. PLEASE CALL SERVICE DIRECT FOR UP TO DATE INFORMATION. Any changes or new services identified please send to [email protected] AMMAN GWEDRAETH Rwyth Cabs currently operate 20 Licensed Taxis including 1-8 Seaters.There are 10 Drivers who are registered with the Local Authority and who have Full DBS Certification. There is Disability access. The company are based in and operate 15 miles from Pontyates Nr Llanelli SA15 STB. Can assist with collection of goods medical supplies and other, in addition to the conveyance of persons etc this list is not exhaustive. A 24/7 Service can be offered. Any queries please call 01267 468250 07791 085096/07905 462519, Jamie, Tracey, or Martin VERIFIED Watkins Grocery, 10 Heol Y Neuadd, Tumble , 01269 832856, meal delivery and grocery deliveries, Ty Dyffryn delivery every Monday at 2.30pm, Thursday at 3.30pm. VERIFIED The Y Farchnad Fach Ltd, 4 Bethesda Rd, Tumble,Llanelli,Dyfed,SA14 6HY, Tel: 01269 844555, they deliver to quite a large area groceries and fuel (gas and coal) and also do a hot meal delivery service. Shop in Capel Hendre also Please phone for further details. VERIFIED Canolfan Maerdy, New Rd, Tairgwaith, Ammanford SA18 1UP, 01269 826893 Community food Hub and centre, Community Car, Canolfan Maerdy can provide online access for CAB advice and essential services. Open weekdays, The Food Hub is open 10.30 to 3pm and has some still has food available, with further food incoming daily - There is access to computers for those needing to go online - The Community Car is still operating for those that need it. -

Arthurian Personal Names in Medieval Welsh Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberystwyth Research Portal ʹͲͳͷ Summary The aim of this work is to provide an extensive survey of the Arthurian personal names in the works of Beirdd y Tywysogion (the Poets of the Princes) and Beirdd yr Uchelwyr (the Poets of the Nobility) from c.1100 to c.1525. This work explores how the images of Arthur and other Arthurian characters (Gwenhwyfar, Llachau, Uthr, Eigr, Cai, Bedwyr, Gwalchmai, Melwas, Medrawd, Peredur, Owain, Luned, Geraint, Enid, and finally, Twrch Trwyth) depicted mainly in medieval Welsh prose tales are reflected in the works of poets during that period, traces their developments and changes over time, and, occasionally, has a peep into reminiscences of possible Arthurian tales that are now lost to us, so that readers will see the interaction between the two aspects of middle Welsh literary tradition. Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................... 3 Bibliographical Abbreviations and Short Titles ....................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1: Possible Sources in Welsh and Latin for the References to Arthur in Medieval Welsh Poetry .............................................................................................. 17 1.1. Arthur in the White Book of Rhydderch and the