Relationship Science Informed Clinically Relevant Behaviors in Functional MARK Analytic Psychotherapy: the Awareness, Courage, and Love Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steps Toward the Ripening of Relationship Science

Personal Relationships, 14 (2007), 1–23. Printed in the United States of America. Copyright Ó 2007 IARR. 1350-4126=07 DISTINGUISHED SCHOLAR ARTICLE Steps toward the ripening of relationship science HARRY T. REIS The University of Rochester Harry T. Reis is professor of psychology in the Department of Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology at the Uni- versity of Rochester. He first studied human relationships at the City College of New York, where he received a B.S. in 1970. Reis subsequently received a Ph.D. from New York University in 1975. A former president of the International Society for the Study of Personal Relationships (2000– 2001), he served as editor of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Interpersonal and Group Processes (1986–1990) and is currently editor of Current Directions in Psychological Science. After 10 years as its executive offi- cer (1995–2004), the Society for Personality and Social Psychology awarded him the Distinguished Service Award (2006) and elected him as president (2007). Reis served as member or Chair of the American Psychological Associa- tion’s Board of Scientific Affairs from 2001 through 2003, is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association and of the Association for Psychological Science, and was a Ful- bright Senior Research Fellow in the Netherlands in 1991. Reis’s research, which concerns mechanisms that regulate interpersonal processes, has been funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Abstract Recent decades have seen remarkable growth in research and theorizing about relationships. E. -

7-A-Dyadic-Partner-Schema.Pdf

Clinical Psychology Review 70 (2019) 13–25 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Clinical Psychology Review journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/clinpsychrev Review A dyadic partner-schema model of relationship distress and depression: T Conceptual integration of interpersonal theory and cognitive-behavioral models ⁎ Jesse Lee Wilde, David J.A. Dozois Department of Psychology, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada HIGHLIGHTS • Presents a new theoretical framework – the dyadic partner-schema model of depression • Partner-schema structures affect biased cognitions about one's partner, which lead to maladaptive interpersonal behaviors • Reviews theoretical and empirical support for the model's proposed processes • Discusses implications for research and clinical applications ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Difficulties in romantic relationships are a prominent part of the disorder for many individuals with depression. Depression Researchers have called for an integration of interpersonal and cognitive-behavioral theories to better under- Interpersonal difficulties stand the role of relational difficulties in depression. In this article, a novel theoretical framework (the dyadic Partner-schemas partner-schema model) is presented. This model illustrates a potential pathway from underlying “partner- Romantic relationships schema” structures to romantic relationship distress and depressive affect. This framework integrates cognitive- Schema behavioral mechanisms in depression with research on dyadic processes in romantic -

Science of Relationships / 1

SCIENCE OF RELATIONSHIPS / 1 The Science of Relationships: Answers to Your Question about Dating, Marriage, & Family Edited by: Gary W. Lewandowski, Jr., Timothy J. Loving, Benjamin Le, & Marci E. J. Gleason Contributing Authors: Jennifer J. Harman, Jody L. Davis, Lorne Campbell, Robin S. Edelstein, Nancy E. Frye, Lisa A. Neff, M. Minda Oriña, Debra Mashek, & Eshkol Rafaeli Copyright © 2013 Dr. L Industries, LLC All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher. Kendall-Hunt Publishing Company previously published an earlier version of this book. www.ScienceOfRelationships.com SCIENCE OF RELATIONSHIPS / 2 Preface You might be wondering "why do we need another book on relationships?" Well, if the book in question is like all of the existing books out there, in that it offers the opinion of a single author...the answer is we don't need another book on relationships – at least like that. What we do need is a book on relationships that takes a new approach. Thankfully, the book you are about to read represents a new way of writing about relationships. Up to this point, if you wanted to learn about relationships the most common way to do so was to read a traditional self-help or advice book, read an advice page on the Internet, or pick up a magazine from the check-out line at the store. Other options, though largely underutilized, would be to take a college course on relationships or read the hundreds of scientific articles that relationship scholars publish annually in academic journals. -

Interpersonal Relations Psychology 359 – Section 52561R – 4 Units Location: SAL 101 Fall 2012 - MW - 12:00-1:50Pm

Barone PSY 359 1 Interpersonal Relations Psychology 359 – Section 52561R – 4 Units Location: SAL 101 Fall 2012 - MW - 12:00-1:50pm Instructor: C. Miranda Barone, PhD Office: SGM 529 Phone: (213) 740-5504 (email preferred) E-mail: [email protected] Hours: MW 10:30 – 11:30 a.m. or by appointment Teaching Assistants: Aditya Prasad Office: SGM 1013 Email: [email protected] Keiko Kurita SGM 913 [email protected] Office hours: by appointment Required Text: Miller, R., Intimate Relationships, 6th Edition, McGraw-Hill Companies ISBN- 13 9780078117152 Additional Readings are available through BlackBoard. Course Description and Objectives This course is designed as an overview to the field of interpersonal relationships. The major theories of close relationships will be emphasized, including examinations of attraction, attachment, social cognition, communication, interdependence. In addition, we will examine the difference between casual and intimate relationships, theories of love, sexuality, and relationship development. Finally, we will discuss common problems in relationships (jealousy, shyness, loneliness, power, and conflict. Course Objectives The major goals and objectives of this course are to help you: 1) Understand current theories and research in the field of interpersonal relationships. Specifically, this course will help further your understanding of topics such as: our need for relationships, interpersonal attraction, love, attachment, communication, relationship maintenance, relationship trajectories, relationship dissolution, jealousy, and infidelity. 2) Recognize how findings from relationship science can be applied to everyday experiences. This goal will be met through completion of a course project. 3) Close relationships are one of the most significant experiences in our lives. For this reason, a major goal of the class is to help you gain a better understanding of yourself, and your relationships. -

Family Development and the Marital Relationship As a Developmental Process

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2020 Family Development and the Marital Relationship as a Developmental Process J. Scott Crapo Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Development Studies Commons Recommended Citation Crapo, J. Scott, "Family Development and the Marital Relationship as a Developmental Process" (2020). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7792. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7792 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAMILY DEVELOPMENT AND THE MARITAL RELATIONSHIP AS A DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESS by J. Scott Crapo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Family and Human Development Approved: Kay Bradford, Ph.D. Ryan B. Seedall, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Co-Chair W. David Robinson, Ph.D. Sarah Schwartz, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Elizabeth B. Fauth, Ph.D. Richard Inouye, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2020 ii Copyright © J. Scott Crapo 2020 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Family Development and the Marital Relationship as a Developmental Process by J. Scott Crapo, Doctor of Philosophy Utah State University, 2020 Major Professors: Kay Bradford, Ph.D., and Ryan B. Seedall, Ph.D. Department: Human Development and Family Studies There is a lack of usable theory designed for studying families developmentally, and not much is understood about how relationships such as marriage change and develop over time beyond predictors of mean levels of satisfaction and likelihood of divorce. -

See Table of Major Requirements

Effective Fall 2018 REQUIREMENTS FOR A MAJOR IN PSYCHOLOGY 3 CORE COURSES: 110 Introduction to Psychology (prerequisite for most courses) 201 Statistical Methods in Psychology (prereq: 110) 205 Research Methods in Psychology (prereq: 201) AT LEAST 8 ADDITIONAL PSYCHOLOGY COURSES, including: § at least 2 from Column A (Row 1 or Row 2) § at least 2 200-level courses § at least 2 from Column B (Row 1 or Row 2) (may include COG SCI 210 and 211) at least 1 from Column C (Row 1 or Row 2) § at least 3 300-level courses § at least 1 from Row 2 A course may count towarD more than one oF these requirements, but the total must be at least 8. FIVE RELATED COURSES (REQUIRED IN ADDITION TO THE ABOVE): Two 200-level mathematics courses plus three additional courses chosen from the following: Mathematics at the 200-level; COG SCI 207; EECS 110, 111, or 130; all courses outside of psychology and cognitive science counting toward the WCAS Area I-Natural Sciences requirement. AP credits in Biology, Chemistry, Environmental Science, and Physics count toward this requirement. With permission, Psych 351 may count toward this requirement instead of as a psychology course. COLUMN A COLUMN B COLUMN C (social/personality/clinical) (cognitive/neuroscience) (cross-cutting/integrative) Row 1-Foundation Courses. Prerequisites other than Psych 110 are shown in parentheses. 204 Social Psychology 212 Introduction to Neuroscience 218 Developmental Psychology 215 Psych of Personality (1 biology course recommended) 245 Presenting Ideas and Data 303 Psychopathology 228 -

DIVERSITY of SAMPLES in RELATIONSHIP SCIENCE 1 How

DIVERSITY OF SAMPLES IN RELATIONSHIP SCIENCE 1 How diverse are the samples used to study intimate relationships? A systematic review Hannah C. Williamson, Jerica X. Bornstein, Veronica Cantu, Oyku Ciftci, Krystan A. Farnish, and Megan T. Schouweiler University of Texas at Austin Draft date: August 11, 2021 Manuscript status: submitted for peer review Major changes to this version: The addition of 21 qualitative studies that had previously been excluded from analysis, and major revisions to the Discussion section. DIVERSITY OF SAMPLES IN RELATIONSHIP SCIENCE 2 Abstract The social and behavioral sciences have long suffered from a lack of diversity in the samples used to study a broad array of phenomena. In an attempt to move toward a more contextually- informed approach, multiple subfields have undertaken meta-science studies of the diversity and inclusion of underrepresented groups in their body of literature. The current study is a systematic review of the field of relationship science aimed at examining the state of diversity and inclusion in this field. Relationship-focused papers published in five top relationship science journals from 2014-2018 (N = 559 articles, containing 771 unique studies) were reviewed. Studies were coded for research methods (e.g., sample source, dyadic data, observational data, experimental design) and sample characteristics (e.g., age, education, income, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation). Results indicate that the modal participant in a study of romantic relationships is 30 years old, White, American, middle-class, college educated, and involved in a different-sex, same-race relationship. Additionally, only 74 studies (10%) focused on traditionally underrepresented groups (i.e., non-White, low-income, and/or sexual and gender minorities). -

Of Memes and Marriage: Toward a Positive Relationship Science

FRANK D. FINCHAM Florida State University STEVEN R. H. BEACH University of Georgia* Of Memes and Marriage: Toward a Positive Relationship Science Marital and family research has tended to focus Selfish Gene, when he offered the concept of on distressed relationships. Reasons for this the meme:Ameme is the conceptual analogue focus are documented before keys to establishing to the gene in that it is the core element of an a positive relationship science are outlined. idea that is transmitted and replicated over time. Increased study of positive affect is needed to Instead of DNA replicating within a physical better understand relationships, and the best milieu, however, the meme replicates within way to accomplish this goal is to embrace a given cultural and conceptual context. Just the construct of ‘‘relationship flourishing.’’ as genes may have multiple alleles, with the The behavioral approach system and the frequency of the alleles being determined by behavioral inhibition system are described and environmental selection pressures, memes may their potential role in understanding positive also have positive and negative forms, and they relationship processes is described using, as may also be subject to selection pressures. examples, commitment and forgiveness. A link If we use this metaphor to examine the liter- to positive psychology is made, and it is ature on marriage and family, we immediately proposed that the study of positive relationships notice that there are many important memes, but constitutes the fourth pillar of this subdiscipline. most concern their negative form in that they Finally, the potential for focus on positive focus on deficits and dysfunction. -

Ebook Download the Psychology of Interpersonal Relations

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF INTERPERSONAL RELATIONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Fritz Heider | 334 pages | 05 Mar 2015 | Martino Fine Books | 9781614277958 | English | none The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations PDF Book The amount of love in any relationship is directly proportional to the above three components. Fritz Heider. Relationship can also develop in a group Relationship of students with their teacher, relationship of a religious guru with his disciples and so on. A strong interpersonal relationship between a man and a woman leads to friendship, love and finally ends in marriage. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations Fritz Heider Psychology Press , - Seiten 1 Rezension As the title suggests, this book examines the psychology of interpersonal relations. Rotter, J. Today, no major research university can afford not to have a relationship course in its psychology curriculum. Contributors present compelling findings on the bidirectional interplay between internal processes, such as self-esteem and self-regulation, and relationship processes, such as how positively partners view each other, whether they. Cite chapter How to cite? An experimental study of apparent behavior. Similar Articles Under - Interpersonal Relationship. San Francisco: Freeman. View All Articles. In intimate relationships there is often, but not always, an implicit or explicit agreement that the partners will not have sex with someone else - monogamy. Sociologists recognize a hierarchy of forms of activity and interpersonal relations , which divides them into: behavior , action , social behavior , social action , social contact , social interaction and finally social relation. It reviews a vast body of knowledge on how interpersonal experiences fundamentally shape an individual's behavior, thoughts, and emotions, sometimes with painful and far-reaching effects. -

Ellen Berscheid, Elaine Hatfield, And

PPSXXX10.1177/1745691613497966Reis et al.The Emergence of Relationship Science 497966research-article2013 Perspectives on Psychological Science 8(5) 558 –572 Ellen Berscheid, Elaine Hatfield, and the © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Emergence of Relationship Science DOI: 10.1177/1745691613497966 pps.sagepub.com Harry T. Reis1, Arthur Aron2, Margaret S. Clark3, and Eli J. Finkel4 1The University of Rochester, 2Stony Brook University, 3Yale University, and 4Northwestern University Abstract In the past 25 years, relationship science has grown from a nascent research area to a thriving subdiscipline of psychological science. In no small measure, this development reflects the pioneering contributions of Ellen Berscheid and Elaine Hatfield. Beginning at a time when relationships did not appear on the map of psychological science, these two scholars identified relationships as a crucial subject for scientific psychology and began to chart its theoretical and empirical territory. In this article, we review several of their most influential contributions, describing the innovative foundation they built as well as the manner in which this foundation helped set the stage for contemporary advances in knowledge about relationships. We conclude by discussing the broader relevance of this work for psychological science. Keywords interpersonal relations, family In 2012, Ellen Berscheid and Elaine Hatfield were (1926) and Terman (1938) conducted some of the earliest awarded the Association for Psychological Science’s investigations of marriage. Yet these works, compelling (APS) highest scientific honor, the William James award, as they were, did not foster a more general interest in for their “pioneering contributions . [to] the science of relationships. Relationship science did not exist as an interpersonal attraction and close relationships, now one identifiable discipline or even subdiscipline at that time. -

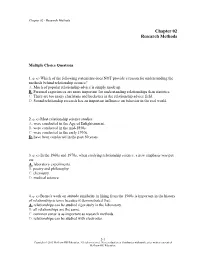

Chapter 02 Research Methods

Chapter 02 - Research Methods Chapter 02 Research Methods Multiple Choice Questions 1. (p. 41) Which of the following statements does NOT provide a reason for understanding the methods behind relationship science? A. Much of popular relationship advice is simply made up. B. Personal experiences are more important for understanding relationships than statistics. C. There are too many charlatans and hucksters in the relationship advice field. D. Sound relationship research has an important influence on behavior in the real world. 2. (p. 42) Most relationship science studies: A. were conducted in the Age of Enlightenment. B. were conducted in the mid-1850s. C. were conducted in the early 1930s. D. have been conducted in the past 50 years. 3. (p. 42) In the 1960s and 1970s, when studying relationship science, a new emphasis was put on: A. laboratory experiments. B. poetry and philosophy. C. chemistry. D. medical science. 4. (p. 42) Byrne's work on attitude similarity in liking from the 1960s is important in the history of relationship science because it demonstrated that: A. relationships can be studied rigorously in the laboratory. B. all relationships are the same. C. common sense is as important as research methods. D. relationships can be studied with electrodes. 2-1 Copyright © 2015 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education. Chapter 02 - Research Methods 5. (p. 42-43) Donn Byrne was one of the first to study _____ in a laboratory. A. liking B. marriage C. divorce D. psychology 6. (p. 43) Today, relationship science: A. -

1 Excerpt from Personality and Close Relationship Processes Stanley O

1 Excerpt from Personality and Close Relationship Processes1 Stanley O. Gaines, Jr. Brunel University London 1 This material is scheduled to be published in Personality and Close Relationship Processes by Stanley O. Gaines, Jr. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re- distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © 2016 Cambridge University Press. 2 Chapter 1: Behaviorist Foundations of the Field of Close Relationships Since the early-to-mid-1980’s, the subject area of interpersonal relations has undergone a remarkable shift in emphasis within social psychology, from a primary focus on attraction (Berscheid, 1985), to a joint focus on attraction and close relationships (Berscheid & Reis, 1998), to a primary focus on close relationships (M. S. Clark & Lemay, 2010). This shift in emphasis within social psychology has coincided with the emergence of a clearly identifiable science of close relationships, which M. S. Clark and Lemay (2010) defined as ongoing human interactions that, over time, serve the functions of “(1) providing both members a sense of security that their welfare has been, and will continue to be protected and enhanced by their [partners’] responsiveness; and (2) providing both members a sense that they, themselves, have been, are, and will continue to be responsive to their partners” (p. 899). Relationship scientists have likened the evolution of their multidisciplinary field to progress through various developmental stages of plants, from “greening” (Berscheid, 1999), to “ripening” (Reis, 2007), to “blossoming” (L. Campbell & Simpson, 2013). One of the most highly regarded theories that paved the way for such conceptual and empirical progress in the field of relationship science since the early- to-mid- 1980s is John Thibaut and Harold Kelley’s (1959; Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) interdependence theory, which contends that partners in close relationships exert mutual influence upon each other’s thoughts, feelings and behavior (Berscheid, 1985).