BEING in the ZONE Simulation, and Staging Retail Theater at ESPN Zone Chicago Implosion Draws Consumers Into a JOHN F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

Disneyland® Park

There’s magic to be found everywhere at The Happiest Place on Earth! Featuring two amazing Theme Parks—Disneyland® Park and Disney California Adventure® Park—plus three Disneyland® Resort Hotels and the Downtown Disney® District, the world-famous Disneyland® Resort is where Guests of all ages can discover wonder, joy and excitement around every turn. Plan enough days to experience attractions and entertainment in 1 both Parks. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 6 Go back and forth between both Theme Parks with a Disneyland® Resort Park Hopper® 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District Ticket. Plus, when you buy a 3+ day ticket before you arrive, you get one Magic Morning* 2 Disney’s Paradise Pier® Hotel Disneyland® Park early admission to select experiences 5 at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the general public on select days. 3 Disney’s Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park *Magic Morning allows one early admission (during the duration of the Theme Park ticket or Southern California CityPASS®) to select attractions, stores, entertainment and dining locations at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the public on Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday. Each member of your travel party must have 3-day or longer Disneyland® Resort tickets. To enhance the Magic Morning experience, it is strongly recommended that Guests arrive at least one hour and 15 minutes prior to regular Park opening. Magic Morning admission is based on availability and does not operate daily. Applicable days and times of operation and all other elements including, but not limited to, operation of attractions, entertainment, stores and restaurants and appearances of Characters may vary and are subject to change without notice. -

For Immediate Release Thor Industries and Cancer

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For Media Inquiries: Richard Riegel Katherine Anson Rob Durkee Bernadette Rae VP - Thor Industries, Inc. Director of Scheduling Executive Director Director Drive Against Prostate Cancer Office of The Mayor Cancer Research Institute ESPN Zone 212-370-1570 212-788-3031 1-800-99-CANCER 212-921-3776 [email protected] [email protected] www.cancerresearch.org [email protected] THOR INDUSTRIES AND CANCER RESEARCH INSTITUTE TEAM UP WITH NEW YORK CITY MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI AND NBA RETIRED PLAYERS TO OFFER FREE PROSTATE CANCER SCREENINGS AT ESPN ZONE IN TIMES SQUARE New York, NY – June 13, 2001— Thor Industries Inc. (NYSE:THO), the developer of The Drive Against Prostate Cancer (“The Drive”), and its partner Cancer Research Institute (“CRI”) will host a press conference with New York City Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani and the NBA Retired Players Association on Thursday, June 14th at 10:00 a.m. at ESPN Zone in Times Square to announce free prostate cancer screenings to men age 40 and over. The Drive will be making its second annual stop in New York City as part of a special focus on prostate cancer surrounding Fathers’ Day. Mayor Giuliani, a prostate cancer survivor, will headline the press event designed to encourage men over 40 to seek annual prostate cancer screenings, consisting of a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test and a Digital Rectal Exam (DRE). According to Mayor Giuliani, “The importance of early detection of prostate cancer cannot be overemphasized. Men must get screened every year.” Mayor Giuliani will be joined by fellow city dignitaries including City Council Member Marty Golden, and fellow prostate cancer survivors Borough President Guy Molinari, former Police Commissioner Howard Safir and former Congressman Herman Badillo. -

Official Rules for Applicants and Contestants

OFFICIAL RULES FOR APPLICANTS AND CONTESTANTS 1. GAME(S) DESCRIPTION: “Dream Job” are reality/game shows (the “Program(s)”) produced by ESPN Productions, Inc. or a producer selected by ESPN Productions, Inc. (“Producer”) for initial telecast on the ESPN, Inc. (“ESPN”) television network known as “ESPN” (the “ESPN Service”). The Program(s) shall include one program concentrating on sportscaster skills (“Program 1”), and one program concentrating on play-by-play skills (“Program 2”). In the Program(s), approximately ten contestants (“Contestants”) will be participants in competition(s) (the “Game(s)”) in which they will be brought to New York, New York to complete a number of sportscaster and/or play-by-play related tasks (“Tasks”). A panel of judges (selected by ESPN) and/or viewers will cast votes and eliminate one or more Contestants after each round of the Program(s). The Game(s) will take place over approximately seven (7) to ten (10) consecutive weeks (the “Game(s) Period”), beginning in or about September 2004 and ending in or about November 2004 with respect to Program 1; and beginning in or about February 2005 and ending in or about March 2005 with respect to Program 2. The winner of the Game(s) will be offered a one (1) year on-air talent contract with ESPN (the “Prize”). Further detailed information about the Game(s), the Program(s) and the Prize(s) are set forth below. Unless specifically so stated, all references in these Rules to the Program(s) include the Game(s). All decisions regarding the Program(s), including but not limited to, Rules, eligibility, Contestant selection, Program(s) production, Game(s) play, Tasks, award of the Prize, are at Producer’s sole and exclusive discretion, are final and not subject to appeal. -

Running Head: ESPN Case Study ESPN Case Study

Running Head: ESPN Case Study 1 ESPN Case Study Jordan Cox-Smith Professor Liz Kerns Central Washington University ESPN Case Study 2 ESPN Executives John Skipper: President of ESPN Inc. John Wildhack: Executive Vice President of Production Christine Driessen: Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Ed Durso: Executive Vice President and Head of Administration ESPN Case Study 3 John A. Walsh: Executive Vice John Kosner: Executive Vice President and Executive Editor President of Digital and Print Media Charles Pagano: Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer Sean Bratches: Executive Vice President and Head of Sales and Marketing ESPN Case Study 4 Norby Williamson: Executive Russell Wolff: Executive Vice Vice President, Head of President and Managing Director Programming of ESPN International Photo Credit: ESPN.com ESPN Case Study 5 Mission Statement ESPN’s mission statement is as followed: “To serve sports fans wherever sports are watched, listened to, discussed, debated, read about or played.” This is where ESPN earned some of its nicknames like “Every Sports Particle Notated”. In our societies thirst for information has increased exponentially and it is essential more now than ever that people have the access to this information across multiple mediums. ESPN has tailored there organization to fit that specific need. Using a variety of media mediums, ESPN has accomplished more than the Rasmussen’s and Eagan thought possible back in 1978. ESPN also has a set of core values that they define their culture with at the organization. Here is ESPN’s statement on their values: “People are our most valuable resource, and care and respect for employees and each other will always be at the heart of our operations. -

Encounter Raises Dorm Safety Issue

C A LIFOR N I A S T A T E U N IV E R S IT Y , F U L L E RTO N Body INSIDE piercings and 2 n BRIEFS: Placentia prepares residents for possible Y2K disaster tattoos —see Opinion 3 nNEWS: ROTC cadets finish fourth in page 4 Ranger Challenge VOLUME 69, I SSUE 36 WEDNESDAY N OVEMBER 10, 1999 Familiar Yee-haw! Encounter faces win AS raises dorm nGOVERNMENT: Arts safety issue rep Evan Mooney sug- gests greater recruit- nCAMPUS: CSUF “We’ve never had a front door kicked off the hinges because ment effort public safety officers someone wanted to get it. It was always either left unlocked or BY NICOLE BURNS make a routine of somebody opened the door.” Staff Writer According to Eugene Shang, patrolling the dorms director of the Residence Halls, Four of Cal State Fullerton’s seven walk-throughs of all dorm areas schools voted in favor of incumbent BY AMY NIELSEN are commonplace as a preventa- candidates in last week’s Associated Staff Writer tive measure to help ensure the Students election. safety of the residence. Although some of the races were Going off to college, being on Upon moving into the residence contested by write-in nominees, bal- your own for the first time and halls, each resident is advised of lots for each school suggested that the living in the dorms can be excit- the general safety precautions that race as a whole was uncontested. ing experiences for many young need to be observed, including the Evan Mooney, incumbent repre- people. -

Walt Disney: Eyes on Hong Kong

WALT DISNEY: EYES ON HONG KONG by CHOR SEE-YU 左斯宇 LI CHUAN-BEI 李川北 MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented to The Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THREE-YEAR MBA PROGRAMME THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG May 2000 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this project. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the project in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. L /纪,s权書園 ':一-—.. ”途 二 1 5 SEP -—:〔⑶js j . U�.:'|.:PS!T Y 湖 \ ‘, ...-�、/ pv-TtM /-<-// ,.‘鮮:…,、, APPROVAL Name: Chor See-Yu , Li Chuan-Bei Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Walt Disney: Eyes on Hong Kong (JNamjg;;^iifcervisor) Date Approved : I气/今/ ii Executive Summary Walt Disney has developed its enteitaimnent kingdom for over 75 years and earned great reputation. However, in recent years its performance is under investors ‘ expectation and causing the flattened share price. Intensive competitive environment with talented new entrants makes the environment of the company become more difficult. Moreover, heavy investment in IT (information technology) business, such as Infoseek, gives the company extra burden. All these factors drive the company into less profitable year. It is time for the company to review the current situation and formulate a new strategy to lighten the burden and re-build the confidence of investors. This paper is trying to give Disney advice on how to deal with the problems. The core competencies of Walt Disney are its innovative management team and its long history with good reputation in entertaining industry. -

The Effectiveness of Zoning in Solidifying Downtown Retail

The Effectiveness of Zoning in Solidifying Downtown Retail By Alexandra B. Jacobson B.A. in International Relations, 1994 Boston University Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2001 ( 2001 Alexandra B. Jacobson. All Rights Reserved. R/vo- The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Author Department of ban Studies and Planning A May 17, 20W Certified by Professor Terry C'zold Department of Urban Studies and Planning A Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Professor Dennis Frenchman Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning The Effectiveness of Zoning in Solidifying Downtown Retail By Alexandra B. Jacobson Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 17, 2001 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT Once the downtown was the regional hub of shopping, but the downtown retail sector has faced significant struggles to stay alive against the forces of suburban shopping malls, big box retailers, and the dominance of downtown office uses. Recognizing the importance of retail to provide services and bring vitality to the downtown, many cities in the United States have responded by modifying their zoning regulations. New regulations have introduced retail use requirements, street level design standards, and incentives to reward developers for incorporating retail spaces. By exploring examples in three U.S. cities, namely Washington D.C., Boston, and Seattle, this thesis looks at how effectively zoning has worked to solidify the downtown retail core and how other factors influence the existence, character and form of downtown retail. -

News Release

For Immediate Release EARL OF SANDWICH JOINS DOWNTOWN DISNEY The World’s Greatest Hot Sandwich® Available this Summer at the Disneyland Resort ANAHEIM, CALIF. — Feb. 7, 2012 — Disneyland Resort today announced that Earl of Sandwich will open a new location at Downtown Disney in early summer 2012. The restaurant will offer guests a unique, casual- quick dining option while visiting Downtown Disney. “We pride ourselves in giving our guests a unique experience at Downtown Disney through different retail and food offerings,” said Tony Bruno, vice president of Resort Hotels and Downtown Disney. “This will be the only Earl of Sandwich in California and it is sure to be a favorite among our guests as it has been at Walt Disney World for nearly eight years.” The new restaurant, which continues to have historical ties to the inventor of the sandwich, the Sandwich family, will be adjacent to AMC Theatres. Signature hot sandwiches will be available including The Original 1762, a sandwich of freshly roasted beef, sharp cheddar and creamy horseradish sauce all on freshly baked artisan bread. Soups, salads, wraps and desserts also are on the menu. Earl of Sandwich offers a vast array of hot and cold beverages including The Earl’s Grey Lemonade. Breakfast sandwiches and pastries will be available in the morning and a variety of catering options will be offered at this location. “We are looking forward to the grand opening of our newest location at the Disneyland Resort,” stated Robert Earl, chairman of Earl of Sandwich. “The success we’ve experienced at Walt Disney World, Disneyland Paris and our other 15 locations has proven that the quality of our food and our dining experience will bring guests back time and time again.” Earl of Sandwich joins approximately 50 retail, dining and entertainment venues that comprise Downtown Disney. -

The NCAA: Mascots and Minorities

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 11-16-2005 The NCAA: mascots and minorities Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "The NCAA: mascots and minorities" (2005). On Sport and Society. 680. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/680 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE The NCAA: mascots and minorities NOVEMBER 16, 2005 It is here! "ESPN Mobile" has arrived. It will join ESPN, ESPN2, ESPN Classic, ESPNU, ESPNews, ESPN Radio, ESPN International, ESPN.com, ESPN The Magazine, ESPN Original Entertainment, ESPN Merchandise, ESPN Zone, ESPN Enterprises, ESPN Regional Television, ESPN Now, ESPN Extra, ESPN HD, and Sports Ticker Enterprises, in the ESPN family. ESPN has taken "ubiquity" to the next level. It is ready when you are, it's got you covered, it's like having an entire sports universe in your pocket. ESPN, The Family, makes the Bushes and the Corleone’s look like small time operators. It would seem that the most likely next step must be "ESPN Your Life," an electronic multiplex that will allow the subscriber to be completely engulfed by SportsWorld and terminate all other forms of existence. -

Extra Smiles, Offers, and Benefits, Just for Disney Vacation Club Members

T:8.5” S:8” Disneyland® Resort January – December 2016 Extra smiles, offers, and benefi ts, just for Disney Vacation Club Members in 2016! Membership Magic opens up a world of value, fl exibility, and Membership Extras for you and your family. As a Disney Vacation Club Member, you know Membership is magical – you can stretch your vacation dollars and vacation when, where, and how often you want at our unique Disney Vacation Club Resorts. Plus, Members have the option of exploring thousands of other destinations in locations around the world. But it gets even better! Membership Magic brings you a selection of exclusive Membership Extras – so no matter where you go within our Disney Vacation Club Resorts and Theme Parks, you’ll fi nd even more reasons to smile. And while you’re at Disneyland® Resort, you can enjoy these exclusive experiences and special offers by presenting your Disney Vacation Club Membership Card and a valid photo I.D. Visit disneyvacationclub.com for the most up-to-date information about Membership Magic. Please see reverse for important details and block-out dates. Dining Shopping All restaurant discounts are valid for a maximum party of eight, Disneyland® Resort Merchandise – 10% off at all Disney-owned-and- including the Member. Theme Park admission is required, but not operated merchandise locations. included. For reservations call (714) 781-DINE (781-3463), or book online at disneyland.disney.go.com/dining. Downtown Disney® District – Free stamped design matting. 10% off at the following locations: Caricatures ESPN Zone – Receive double points in the Interactive Sports Arena, ® Paradise Garden Grill Disneyland Park when purchasing a new game card. -

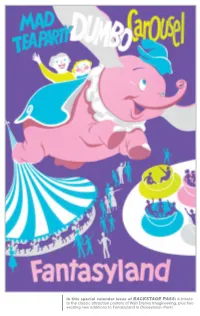

In This Special Calendar Issue of BACKSTAGE PASS

In this special calendar issue of BACKSTAGE PASS: A tribute to the classic attraction posters of Walt Disney Imagineering, plus two exciting new additions to Fantasyland in Disneyland® Park! “Hello to all of our Disneyland® Resort Passholders!” As many of you have heard, I have just returned to Southern California as president of the Disneyland® Resort. Like many of you, my excitement and passion for The Happiest Place on Earth began when my parents brought me to the Park when I was a child. I remember eating popcorn on Main Street, U.S.A., meeting Mickey Mouse for the first time, and never wanting to leave. That first trip—and all of the trips that followed with my parents, friends, and now with my own family—created memories that I will never forget. And that, after all, is what the Disneyland® Resort is all about. After meeting hundreds of Cast Members and Guests throughout my first couple of weeks, I can’t tell you how excited I am to be here and how proud I am to be part of this team. As you are aware, the past year has been an incredibly Michael Colglazier, exciting one at the Disneyland® Resort with the openings of President, Disneyland® Resort Buena Vista Street, Cars Land, and most recently, Fantasy Faire. We’ve also been working to enhance your Passholder experience through Limited Time Annual Passholder Magic which will give you even more opportunities to create lifelong memories with your friends and families. More Limited Time Annual Passholder Magic means more reasons this is the best year ever to be an Annual Passholder! On behalf of all of the Cast Members at the Disneyland® Resort, thank you for being part of our family.