The Effectiveness of Zoning in Solidifying Downtown Retail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1998 National Collegiate Women's Gymnastics

2020 MPSF Indoor Track & Field CHAMPIONSHIPS TEAM PARTICIPANT MANUAL UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON SEATTLE, WA FEBRUARY 28 – FEBRUARY 29, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Championship Personnel .................................................. 2 2. Schedule of Events ......................................................... 3-4 3. Meet Information ............................................................... 5 4. Entries .................................................................................. 5 5. Accommodations/Hotels .................................................. 5 6. Awards ................................................................................ 5 7. Admission ........................................................................... 5 8. Meeting & Agenda ......................................................... 5-6 9. Transportation & Travel Information ............................. 6 10. Entrances & Parking .......................................................... 7 11. Training Room/Medical Information .............................. 7 12. Officials ................................................................................ 7 13. Team Camps ....................................................................... 7 14. Uniforms .............................................................................. 7 15. Videotaping & Cameras .................................................... 7 16. Warm-ups ............................................................................ 8 17. Championship T-shirts ..................................................... -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

Disneyland® Park

There’s magic to be found everywhere at The Happiest Place on Earth! Featuring two amazing Theme Parks—Disneyland® Park and Disney California Adventure® Park—plus three Disneyland® Resort Hotels and the Downtown Disney® District, the world-famous Disneyland® Resort is where Guests of all ages can discover wonder, joy and excitement around every turn. Plan enough days to experience attractions and entertainment in 1 both Parks. 5 INTERSTATE 4 5 2 3 6 Go back and forth between both Theme Parks with a Disneyland® Resort Park Hopper® 1 Disneyland® Hotel 4 Downtown Disney® District Ticket. Plus, when you buy a 3+ day ticket before you arrive, you get one Magic Morning* 2 Disney’s Paradise Pier® Hotel Disneyland® Park early admission to select experiences 5 at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the general public on select days. 3 Disney’s Grand Californian Hotel® & Spa 6 Disney California Adventure® Park *Magic Morning allows one early admission (during the duration of the Theme Park ticket or Southern California CityPASS®) to select attractions, stores, entertainment and dining locations at Disneyland® Park one hour before the Park opens to the public on Tuesday, Thursday or Saturday. Each member of your travel party must have 3-day or longer Disneyland® Resort tickets. To enhance the Magic Morning experience, it is strongly recommended that Guests arrive at least one hour and 15 minutes prior to regular Park opening. Magic Morning admission is based on availability and does not operate daily. Applicable days and times of operation and all other elements including, but not limited to, operation of attractions, entertainment, stores and restaurants and appearances of Characters may vary and are subject to change without notice. -

For Immediate Release Thor Industries and Cancer

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For Media Inquiries: Richard Riegel Katherine Anson Rob Durkee Bernadette Rae VP - Thor Industries, Inc. Director of Scheduling Executive Director Director Drive Against Prostate Cancer Office of The Mayor Cancer Research Institute ESPN Zone 212-370-1570 212-788-3031 1-800-99-CANCER 212-921-3776 [email protected] [email protected] www.cancerresearch.org [email protected] THOR INDUSTRIES AND CANCER RESEARCH INSTITUTE TEAM UP WITH NEW YORK CITY MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI AND NBA RETIRED PLAYERS TO OFFER FREE PROSTATE CANCER SCREENINGS AT ESPN ZONE IN TIMES SQUARE New York, NY – June 13, 2001— Thor Industries Inc. (NYSE:THO), the developer of The Drive Against Prostate Cancer (“The Drive”), and its partner Cancer Research Institute (“CRI”) will host a press conference with New York City Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani and the NBA Retired Players Association on Thursday, June 14th at 10:00 a.m. at ESPN Zone in Times Square to announce free prostate cancer screenings to men age 40 and over. The Drive will be making its second annual stop in New York City as part of a special focus on prostate cancer surrounding Fathers’ Day. Mayor Giuliani, a prostate cancer survivor, will headline the press event designed to encourage men over 40 to seek annual prostate cancer screenings, consisting of a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test and a Digital Rectal Exam (DRE). According to Mayor Giuliani, “The importance of early detection of prostate cancer cannot be overemphasized. Men must get screened every year.” Mayor Giuliani will be joined by fellow city dignitaries including City Council Member Marty Golden, and fellow prostate cancer survivors Borough President Guy Molinari, former Police Commissioner Howard Safir and former Congressman Herman Badillo. -

Official Rules for Applicants and Contestants

OFFICIAL RULES FOR APPLICANTS AND CONTESTANTS 1. GAME(S) DESCRIPTION: “Dream Job” are reality/game shows (the “Program(s)”) produced by ESPN Productions, Inc. or a producer selected by ESPN Productions, Inc. (“Producer”) for initial telecast on the ESPN, Inc. (“ESPN”) television network known as “ESPN” (the “ESPN Service”). The Program(s) shall include one program concentrating on sportscaster skills (“Program 1”), and one program concentrating on play-by-play skills (“Program 2”). In the Program(s), approximately ten contestants (“Contestants”) will be participants in competition(s) (the “Game(s)”) in which they will be brought to New York, New York to complete a number of sportscaster and/or play-by-play related tasks (“Tasks”). A panel of judges (selected by ESPN) and/or viewers will cast votes and eliminate one or more Contestants after each round of the Program(s). The Game(s) will take place over approximately seven (7) to ten (10) consecutive weeks (the “Game(s) Period”), beginning in or about September 2004 and ending in or about November 2004 with respect to Program 1; and beginning in or about February 2005 and ending in or about March 2005 with respect to Program 2. The winner of the Game(s) will be offered a one (1) year on-air talent contract with ESPN (the “Prize”). Further detailed information about the Game(s), the Program(s) and the Prize(s) are set forth below. Unless specifically so stated, all references in these Rules to the Program(s) include the Game(s). All decisions regarding the Program(s), including but not limited to, Rules, eligibility, Contestant selection, Program(s) production, Game(s) play, Tasks, award of the Prize, are at Producer’s sole and exclusive discretion, are final and not subject to appeal. -

Historic Roots. 1500 Fourth Avenue | Seattle

PRIMARY LOGO DESIGN VARIATIONS OF LOGO COLOR PALETTE Primary MODERN WORKPLACE. HISTORIC ROOTS. 1500 FOURTH AVENUE | SEATTLE MODERN UPGRADES LOCATION IS KEY PARKING GALORE Upcoming building Phenomenal retail, No parking? No problem! renovations will bring the shopping therapy, Over 17 parking garages modern & vintage together delicious lunch & are within a 3-block radius for a new generation of dinner options are all of the Seaboard Building. creative office space needs. within a block or less of the building. Secure, on-site bike Flexible floor plate storage and showers configurations and on-site Westlake Park is the available for tenants. amenities will be added for activated heart of Seattle. the modern office tenant. Daily rotating food truck Metro, commuter buses, offerings are right out your and Link Light Rail are right door! outside your door. PRIMARY LOGO DESIGN VARIATIONS OF LOGO COLOR PALETTE Primary 1500 FOURTH AVENUE | SEATTLE BUILDING HISTORY The Seaboard Building, designated a National Historic Landmark in 2002, is located in the heart of downtown Seattle. Rising above Westlake Center, the Seaboard Building with its beautiful terra cotta facade was constructed in 1907 as the Northern Bank and Trust Building. Today, the building is home to a mix of urban residential city homes, offices and retail space. PRIMARY LOGO DESIGN VARIATIONS OF LOGO COLOR PALETTE Primary VIEW FROM 1500 FOURTH AVENUE | SEATTLE BUILDING FACTS YEAR BUILT 19 07 YEAR RENOVATED 2001 BUILDING SF 58,180 SF RENTAL RATES $42.00 - $44.00/SF, Full Service BUILDING -

Running Head: ESPN Case Study ESPN Case Study

Running Head: ESPN Case Study 1 ESPN Case Study Jordan Cox-Smith Professor Liz Kerns Central Washington University ESPN Case Study 2 ESPN Executives John Skipper: President of ESPN Inc. John Wildhack: Executive Vice President of Production Christine Driessen: Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Ed Durso: Executive Vice President and Head of Administration ESPN Case Study 3 John A. Walsh: Executive Vice John Kosner: Executive Vice President and Executive Editor President of Digital and Print Media Charles Pagano: Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer Sean Bratches: Executive Vice President and Head of Sales and Marketing ESPN Case Study 4 Norby Williamson: Executive Russell Wolff: Executive Vice Vice President, Head of President and Managing Director Programming of ESPN International Photo Credit: ESPN.com ESPN Case Study 5 Mission Statement ESPN’s mission statement is as followed: “To serve sports fans wherever sports are watched, listened to, discussed, debated, read about or played.” This is where ESPN earned some of its nicknames like “Every Sports Particle Notated”. In our societies thirst for information has increased exponentially and it is essential more now than ever that people have the access to this information across multiple mediums. ESPN has tailored there organization to fit that specific need. Using a variety of media mediums, ESPN has accomplished more than the Rasmussen’s and Eagan thought possible back in 1978. ESPN also has a set of core values that they define their culture with at the organization. Here is ESPN’s statement on their values: “People are our most valuable resource, and care and respect for employees and each other will always be at the heart of our operations. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

Encounter Raises Dorm Safety Issue

C A LIFOR N I A S T A T E U N IV E R S IT Y , F U L L E RTO N Body INSIDE piercings and 2 n BRIEFS: Placentia prepares residents for possible Y2K disaster tattoos —see Opinion 3 nNEWS: ROTC cadets finish fourth in page 4 Ranger Challenge VOLUME 69, I SSUE 36 WEDNESDAY N OVEMBER 10, 1999 Familiar Yee-haw! Encounter faces win AS raises dorm nGOVERNMENT: Arts safety issue rep Evan Mooney sug- gests greater recruit- nCAMPUS: CSUF “We’ve never had a front door kicked off the hinges because ment effort public safety officers someone wanted to get it. It was always either left unlocked or BY NICOLE BURNS make a routine of somebody opened the door.” Staff Writer According to Eugene Shang, patrolling the dorms director of the Residence Halls, Four of Cal State Fullerton’s seven walk-throughs of all dorm areas schools voted in favor of incumbent BY AMY NIELSEN are commonplace as a preventa- candidates in last week’s Associated Staff Writer tive measure to help ensure the Students election. safety of the residence. Although some of the races were Going off to college, being on Upon moving into the residence contested by write-in nominees, bal- your own for the first time and halls, each resident is advised of lots for each school suggested that the living in the dorms can be excit- the general safety precautions that race as a whole was uncontested. ing experiences for many young need to be observed, including the Evan Mooney, incumbent repre- people. -

Walt Disney: Eyes on Hong Kong

WALT DISNEY: EYES ON HONG KONG by CHOR SEE-YU 左斯宇 LI CHUAN-BEI 李川北 MBA PROJECT REPORT Presented to The Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION THREE-YEAR MBA PROGRAMME THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG May 2000 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this project. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the project in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. L /纪,s权書園 ':一-—.. ”途 二 1 5 SEP -—:〔⑶js j . U�.:'|.:PS!T Y 湖 \ ‘, ...-�、/ pv-TtM /-<-// ,.‘鮮:…,、, APPROVAL Name: Chor See-Yu , Li Chuan-Bei Degree: Master of Business Administration Title of Project: Walt Disney: Eyes on Hong Kong (JNamjg;;^iifcervisor) Date Approved : I气/今/ ii Executive Summary Walt Disney has developed its enteitaimnent kingdom for over 75 years and earned great reputation. However, in recent years its performance is under investors ‘ expectation and causing the flattened share price. Intensive competitive environment with talented new entrants makes the environment of the company become more difficult. Moreover, heavy investment in IT (information technology) business, such as Infoseek, gives the company extra burden. All these factors drive the company into less profitable year. It is time for the company to review the current situation and formulate a new strategy to lighten the burden and re-build the confidence of investors. This paper is trying to give Disney advice on how to deal with the problems. The core competencies of Walt Disney are its innovative management team and its long history with good reputation in entertaining industry. -

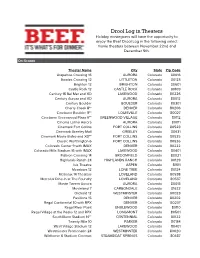

Drool Log in Theaters

Drool Log in Theaters Holiday moviegoers will have the opportunity to enjoy the Beef Drool Log in the following select movie theaters between November 22nd and December 5th. On-Screen Theater Name City State Zip Code Arapahoe Crossing 16 AURORA Colorado 80016 Bowles Crossing 12 LITTLETON Colorado 80123 Brighton 12 BRIGHTON Colorado 80601 Castle Rock 12 CASTLE ROCK Colorado 80109 Century 16 Bel Mar and XD LAKEWOOD Colorado 80226 Century Aurora and XD AURORA Colorado 80012 Century Boulder BOULDER Colorado 80301 Cherry Creek 8** DENVER Colorado 80206 Cinebarre Boulder 11** LOUISVILLE Colorado 80027 Cinebarre Greenwood Plaza 6** GREENWOOD VILLAGE Colorado 80112 Cinema Latino Aurora AURORA Colorado 80011 Cinemark Fort Collins FORT COLLINS Colorado 80528 Cinemark Greeley Mall GREELEY Colorado 80631 Cinemark Movie Bistro and XD** FORT COLLINS Colorado 80525 Classic Worthington 6 FORT COLLINS Colorado 80526 Colorado Center 9 with IMAX DENVER Colorado 80222 Colorado Mills Stadium 16 with IMAX LAKEWOOD Colorado 80401 Flatiron Crossing 14 BROOMFIELD Colorado 80021 Highlands Ranch 24 HIGHLANDS RANCH Colorado 80129 Isis Theatre ASPEN Colorado 81611 Meadows 12 LONE TREE Colorado 80124 Metrolux 14 Theaters LOVELAND Colorado 80538 Metrolux Dine-In at The Foundry LOVELAND Colorado 80537 Movie Tavern Aurora AURORA Colorado 80013 Movieland 7 CARBONDALE Colorado 81623 Orchard 12 WESTMINSTER Colorado 80023 Pavilions 15 DENVER Colorado 80202 Regal Continental 10 with RPX DENVER Colorado 80237 Regal River Point ENGLEWOOD Colorado 80110 Regal Village at the -

Liquor Control Board to Pilot Holiday Gift Stores in Four Shopping Malls Published on Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (

Liquor Control Board to pilot holiday gift stores in four shopping malls Published on Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board (https://lcb.wa.gov) Liquor Control Board to pilot holiday gift stores in four shopping malls Oct 16, 2009 OLYMPIA The Washington State Liquor Control Board (WSLCB) will open Liquor and Wine holiday gift stores in four Western Washington shopping malls this holiday season. The stores will be open from Nov. 1 through Dec. 31. The WSLCB is running this pilot program for two reasons. 1. To generate $3.8 million in additional revenue during the 2009 and 2010 holiday seasons to help offset the state budget deficit; and 2. To determine customer interest in shopping at these gift locations during the holidays. The holiday gift stores will carry spirit gift packages and a limited selection of spirits, wine, and spirits- based chocolates and eggnogs. The stores will be open seven days a week. Store hours will vary by location. Mall locations The WSLCB will open holiday gift stores at the following malls: Alderwood Mall, 3000 184th St. S.W. in Lynnwood Bellis Fair Mall, One Bellis Fair Parkway in Bellingham The Commons at Federal Way, 1928 S. Commons in Federal Way Pacific Place, 600 Pine Street in Seattle This is the first time the WSLCB has opened holiday gift stores in shopping malls. The store sites were selected based on location, proximity to other liquor stores, cost and size. Customers are invited to send comments about the holiday gift stores to [email protected]. - 30 - Copyright © 2021 Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board Page 1 of 1.