2016 Ezgi Varli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Article} {Profile}

{PROFILE} {PROFILE} {FEATURE ARTICLE} {PROFILE} 28 {OUTLINE} ISSUE 4, 2013 Photo Credit: Sharon Givoni {FEATURE ARTICLE} Street Art: Another Brick in the Copyright Wall “A visual conversation between many voices”, street art is “colourful, raw, witty” 1 and thought-provoking... however perhaps most importantly, a potential new source of income for illustrators. Here, Melbourne-based copyright lawyer, Sharon Givoni, considers how the laws relating to street art may be relevant to illustrators. She tries to make you “street smart” in an environment where increasingly such creations are not only tolerated, but even celebrated. 1 Street Art Melbourne, Lou Chamberlin, Explore Australia Publishing Pty Ltd, 2013, Comments made on the back cover. It canvasses: 1. copyright issues; 2. moral rights laws; and 3. the conflict between intellectual property and real property. Why this topic? One only needs to drive down the streets of Melbourne to realise that urban art is so ubiquitous that the city has been unofficially dubbed the stencil graffiti capital. Street art has rapidly gained momentum as an art form in its own right. So much so that Melbourne-based street artist Luke Cornish (aka E.L.K.) was an Archibald finalist in 2012 with his street art inspired stencilled portrait.1 The work, according to Bonham’s Auction House, was recently sold at auction for AUD $34,160.00.2 Stencil seen in the London suburb of Shoreditch. Photo Credit: Chris Scott Artist: Unknown It is therefore becoming increasingly important that illustra- tors working within the street art scene understand how the law (particularly copyright law) may apply. -

Diorama, Vera Cortês Art Agency, 2012

Opening— Friday, June 1, 10 pm Diorama Alexandre Farto AKA Vhils Av. 24 de Julho, 54 -1ºE 1200-868 Lisboa, PT June 2 – September 8, 2012 The gallery will be closed from T/F +351 213 950 177 Tuesday to Saturday July 28 to September 4 for www.veracortes.com From 2pm to 7pm Summer holidays ALEXANDRE FARTO Na arquitectura actual habita um certo deslumbramento pelo tempo e pelo Como em quase todas as suas obras, o mais interessante da série Diorama DIORAMA espaço, em que tudo parece acontecer em todo o lado, quase em simultâ- encontra-se na habilidade manobrar os tempos de recepção do espectador. neo. O efémero e transitório ergue-se como protagonista do estado fluido de O primeiro momento, muito visível, mas vinculado à técnica, ao método. Texto por David Barro uma vida que muda constantemente de pele na ânsia pelo novo. Nada parece O seguinte, mais subtil, tem mais a ver com o processo e com o tempo, com vincular-se a um lugar concreto e há muito que as cidades deixaram de ser um a desconstrução destrutiva daquilo que flui como resto de um modo natural. lugar estável ou de ter uma forma claramente determinada. E muito menos um É, por isso, uma interrupção da realidade em si, do seu tempo e do seu espaço. movimento coerente. Crescemos mal e rápido demais. O suburbano transbor- Mas o jogo de ancas não é necessariamente uma ruptura da sua continuidade. dou e a cidade desapareceu enquanto unidade. Como na arte, uma realidade Seria mais uma elipse ou essa necessidade contemporânea de acidentar, de substitui outra, ocultando coisas, deixando de mostrar alguns fragmentos. -

Annual Report 2010–11

ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 ANNUAL REPORT 2010–11 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Thapich Gloria Fletcher Dhaynagwidh (Thaynakwith) people The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the Eran 2010 cultural enrichment of all Australians through access aluminium to their national art gallery, the quality of the national 270 cm (diam) collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and National Gallery of Australia, Canberra programs, and the professionalism of Gallery staff. acquired through the Founding Donors 2010 Fund, 2010 Photograph: John Gollings The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, (back cover) corporate governance, administration and financial and Hans Heysen business management. Morning light 1913 oil on canvas In 2010–11, the National Gallery of Australia received 118.6 x 102 cm an appropriation from the Australian Government National Gallery of Australia, Canberra totalling $50.373 million (including an equity injection purchased with funds from the Ruth Robertson Bequest Fund, 2011 of $15.775 million for development of the national in memory of Edwin Clive and Leila Jeanne Robertson collection and $2 million for the Stage 1 South Entrance and Australian Indigenous Galleries project), raised $27.421 million, and employed 262 full‑time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2011 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

RMIT Gallery Exhibition Program 2011 97

RMIT Gallery Exhibition Program 2011 97 1 21 January — 12 March 108 2 September — 5 November China and Revolution: Space invaders: australian . street . History, Parody and Memory in Contemporary Art stencils . posters . paste-ups . zines . stickers The exhibition re-evaluates the Cultural Revolution through propaganda poster art Drawn entirely from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia, the produced in the 1960s and ’70s, as well as through oral histories collected by the first Australian institution to have collected this type of work, this exhibition curators in 2008–2009. It opens dialogue between the past and present with work surveys the past 10 years of Australian street art. Featuring 150 works by over from artists with first hand experience, as well as through the display of original 40 Australian artists, the exhibition celebrates the energy of street-based political posters carrying political and social messages to the Chinese masses. creativity, recognising street stencils, posters, paste-ups, zines and stickers Curator Professor Stephanie Hemelryk Donald, Dean of the School of Media and as comprising a recent chapter in the development of Australian prints and Communication at RMIT University, and Professor Harriet Evans, Coordinator of drawings. Curator Jaklyn Babington, Assistant Curator, International Prints, Asian Studies Research at the University of Westminster. Artists Liu Dahong, Xu Drawings and Illustrated Books, National Gallery of Australia Artists Aeon, Weixin, Li Gongming, Shen Jiawei. Public Program -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew Its Government

The Portuguese Colonial War: Why the Military Overthrew its Government Samuel Gaspar Rodrigues Senior Honors History Thesis Professor Temma Kaplan April 20, 2012 Rodrigues 2 Table of Contents Introduction ..........................................................................................................................3 Before the War .....................................................................................................................9 The War .............................................................................................................................19 The April Captains .............................................................................................................33 Remembering the Past .......................................................................................................44 The Legacy of Colonial Portugal .......................................................................................53 Bibliography ......................................................................................................................60 Rodrigues 3 Introduction When the Portuguese people elected António Oliveira de Salazar to the office of Prime Minister in 1932, they believed they were electing the right man for the job. He appealed to the masses. He was a far-right conservative Christian, but he was less radical than the Portuguese Fascist Party of the time. His campaign speeches appeased the syndicalists as well as the wealthy landowners in Portugal. However, he never was -

Spring 2020 Ear Nd Y 42

Spring 2020 ear nd y 42 ISSUE 190 THE NORTH & WEST MELBOURNE NEWS IS PRODUCED BY VOLUNTEERS AT THE CENTRE: Connecting Community in North & West Melbourne Inc www.centre.org.au A stitch in Pandemic affects time behind the mask policing in the crusader inner suburbs Anna Huynh Nicole Pereira masks. “If they can’t pay the fine, eana Eddington began stitching it generally becomes a debt,” he says. Dgowns to protect front-line A policeman’s lot is not a happy Craig is keenly aware that healthcare workers during the first one (Pirates of Penzance) homelessness isn’t easily solved. lockdown. “It’s a long-term project for housing In the harsher stage-four lockdown, ergeant Craig McIntosh can services. But most of our local the new North Melbourne resident Sgive the lie to that old line. A homeless are reasonably easy to talk found another way to help her policeman for 14 years and now to, and we run several operations community. She turned her sewing based at Melbourne West Police and support programs that involve skills to making masks, and her Station, he loves his work. “I dreaded chatting with them,” he says. efforts have seen her turn out well a desk job and I didn’t want to be He is heartened that recent COVID- over 700. doing the same things day in and related offences are generally milder It all started in her own apartment day out,” he says. than the occasional mayhem of complex. Deana was taking a craft At Melbourne West, Craig’s beat Friday and Saturday nights. -

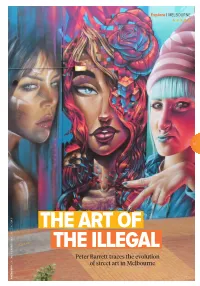

The Art of the Illegal

COMING TO MELBOURNE THIS SUMMER Explore I MELBOURNE Evening Standard 63 THE ART OF ADNATE, SOFLES AND SMUG ADNATE, ARTISTS THE ILLEGAL 11 JAN – 18 FEB PRESENTED BY MTC AND ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE Peter Barrett traces the evolution ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE DEAN SUNSHINE of street art in Melbourne Photo of Luke Treadaway by Hugo Glendinning Photo of Luke Treadaway mtc.com.au | artscentremelbourne.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY Curious-Jetstar_FP AD_FA.indd 1 1/12/17 10:37 am Explore I MELBOURNE n a back alley in Brunswick, a grown man is behaving like a kid. Dean Sunshine should be running his family textiles business. IInstead, the lithe, curly-headed 50-year-old is darting about the bluestone lane behind his factory, enthusiastically pointing out walls filled with colourful artworks. It’s an awesome, open-air gallery, he says, that costs nothing and is in a constant state of flux. Welcome to Dean’s addiction: the ephemeral, secretive, challenging, and sometimes confronting world of Melbourne street art and graffiti. Over the past 10 years, Dean has taken more than 25,000 photographs and produced two + ELLE TRAIL, VEXTA ART SILO DULE STYLE , ADNATE, AHEESCO, books (Land of Sunshine and artist, author and educator, It’s an awesome, Street Art Now) documenting Lou Chamberlin. Burn City: ARTISTS the work of artists who operate Melbourne’s Painted Streets open-air gallery, 64 in a space that ranges from a presents a mind-boggling legal grey area to a downright diversity of artistic expression, he says, that costs illegal one. “I can’t drive along a from elaborate, letter-based street without looking sideways aerosol “pieces” to stencils, nothing and is in down a lane to see if there’s portraits, “paste-ups” (paper something new there,” he says. -

Download Download

The Journal of Public Space ISSN 2206-9658 2018 | Vol. 3 n. 2 https://www.journalpublicspace.org EDITORIAL The Public Voice Maggie McCormick Adjunct Professor, RMIT University, Australia Professor, Reutlingen University, Germany [email protected] SPACE Abstract The Public Voice discusses art and activism in public space through the lens of how art PUBLIC practice is re-territoralising public space. The article begins with a consideration of both commissioned and uncommissioned works that challenge male dominance of public space OF while retaining a traditional relationship between the artist, art and the public. Through a discussion of ‘relational’ public practices from Relational Aesthetic to Community Art to Social Engagement, the article argues that the kind of ‘relational’ art and activism undertaken by the collectives, teams and individuals featured in this issue of The Journal of Public Space is linked by spatial practice as a conduit for social change. By framing their JOURNAL practice through a discussion around her own spatial public practice over time, the author emphasises the impact of urbanisation and digitalisation on the changing nature of THE public space and the public and how the public voice can be mapped through art and activism. Keywords: public space voice, art, activism, urban, spatial, relational, mapping To cite this article: McCormick, M. (2018). The Public Voice. The Journal of Public Space, 3(2), 5-12, DOI 10.32891/jps.v3i2.1107 This article has been accepted for publication in The Journal of Public Space. Please see the Editorial Policies under the ‘About’ section of the journal website for further information. -

Auction License # Ab3131 Auctioneers for This Sale: Frederic Thut, Fl Licence #Au4372

February 13 Catalog.indd 1 2/2/2013 2:07:12 PM INDEX Mario Alberto AGATIELLO 48 Marcos LOPEZ 24bis Julio ALPUY 74/102/105 Alexis AKRITHAKIS 29 / 30 Stevenson MAGLOIRE 22 Erol AKYAVAS 38/39 Fabian MARCACCIO 63 ARMAN 95 Roberto MATTA 88/89/90/91 Jose Yepez ARTEAGA 93 Francisco MATTO 73 Hulusi MERCAN 40 / 41 Stephan Wladislawowitsch BAKALOWICZ 106 Simin MEYKADEH 31 BANKSY 6 / 7 Hector MOLNE 70 Luis Fernando BENEDIT 55/56 Robert MOTHERWELL 19 Cundo BERMUDEZ 67 José Chávez MORADO 57 Oswaldo BORDA 61 Estuardo MALDONADO 47 Mr. BRAINWASH 1 David BURLIUK 33 Hamed NADA 28 Alberto Ulloa BURGOS 81 Hector NAVARRO 54 Hebru BRANTLEY 5 Loiuse NEVELSON 16 Lita CABELLUT 13 Marie ORENSANZ 77 Mario CARRENO 43 Mubin ORHON 35 Eduardo Oliveira CEZAR 51 Ardan OZMENOGLU 15 CHRISTO 18 Gail Sherman CORBETT 190 Manuel PAILOS 98/99/100 Horacio CORDERO 24 A.R. PENCK 17 Rogelio POLESELLO 65/66 Jorge Jiménez DEREDIA 94 Danilo di PRETE 53 Juan A. DIAZ 113/114 Saliba DOUAIHY 42 Anna Maria QUEMARE 111/112/116 Carmelo ARDEN QUIN 44/45/46 Giovanni ECHEVARRIA 115 Carlos ESTEVEZ 58/62 Maurice RENOMA 23 Leopoldo ROMANACH 69 Pedro FIGARI 101 Vitaly RUSAKOV 14 Robert FREEMAN 60 Maria FREIRE 78 SEEN 8 Juan Jose SEGURA 68 Rocío GARCIA 79 David Alfaro SIQUIEROS 64/71 Joaquín Torres GARCIA 92 Venancio SHINKI 52 Diego GIACOMETTI 27 Andres GILES 11 / 12 Kenzo TAKADA 25 Alain GODON 9 Francisco TOLEDO 82/83/84 Greg GOSSEL 96 Michael TRACY 2 / 4 José GURVICH 104 Victor VASARELY 49 Valerie HAMMOND 97 Gregorio VARDANEGA 50 John HARDY 26 Sergei Semyonovich VOROSHILOV 107 Robert INDIANA 21 -

The Post-Dictatorship Memory Politics in Portugal Which Erased Political Violence from the Collective Memory

The post-dictatorship memory politics in Portugal which erased political violence from the collective memory Raquel da Silva, International Development Departmen, University of Birmingham and Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Centro de Estudos Internacionais, Lisbon, Portugal Ana Sofia Ferreira, Institute of Contemporary History, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal Published as: Da Silva, R. and Ferreira, A. (2018) The post-dictatorship memory politics in Portugal that erased political violent activism from the collective memory. Integrative Psychological and Behavioural Science. doi: 10.1007/s12124-018-9452-8 Abstract Former clandestine militants’ voices and stories have been recurrently silenced in the Portuguese “battle over memory”, because their activities were linked to events, such as the Revolution of 25 April 1974, which have themselves been politically and socially depreciated in mainstream political narratives. Only recently did the traditional political narratives start to be questioned and debated by Portuguese scholars. Such political narratives took root in the country in the decades that followed the April Revolution, with various scholars and politicians denying the fascist categorisation of Estado Novo and adopting an authoritarian, non-totalitarian and non-fascist perspective, while recurrently depicting the Revolution as highly negative (namely as the source of the economic troubles of the country). Thus, for a long time, Portuguese conservatives opted to avoid debates on the 48 years of the Estado Novo’s regime which, among other things, maintained a very repressive and violent political police force, a camp of forced labour in Cape Vert known as Tarrafal, and a Colonial War on three African fronts. This article examines the existent academic publications which counter such oblivion of memory regarding armed struggle in Portugal. -

Women on Walls AB 16358935 FINAL

Women on Walls | Engaging street art through the eyes of female artists Alix Maria Beattie Master of Research Thesis Western Sydney University 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I am truly thankful for the support and guidance of my supervisory panel, Dr Rachel Bentley and Professor Lynette Sheridan-Burns. In particular, my primary supervisor Rachel, who not only guided me through my research but offered an endless amount of support, critical engagement and general brainstorming driven by a love of street art. Lynette’s experience, words of encouragement and sharp red pen provided me with the right advice at the right time. I am also thankful to my artists: Mini Graff, Kaff-eine, Buttons, Vexta and Baby Guerrilla. They were generous in their time, thoughts, art, and passion. This work is only possible because of them. To all my lecturers throughout my Master of Research journey – particular Dr Jack Tsonis and Dr Alex Norman – who were tireless in their efforts, helping me become the writer and researcher I am today. Likewise, I want to thank Dominique Spice for creating such a supportive environment for all of us MRes students. To my fellow MRes students - Toshi and in particular Lucie and Beth (aka the awesome clams) – you are all, without doubt the best part of completing this research. Awesome clams, you provided continuous support and good humour –I truly thank you both. Finally, to my friends and family who have been relentless in their support via texts and calls – you know who you are and I am eternally grateful. A special mention and thank you to my wonderful sister Clasina and great friend Tanya, who did a final read through of my thesis.