University of Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

The Rise of Pop

Expos 20: The Rise of Pop Fall 2014 Barker 133, MW 10:00 & 11:00 Kevin Birmingham (birmingh@fas) Expos Office: 1 Bow Street #223 Office Hours: Mondays 12:15-2 The idea that there is a hierarchy of art forms – that some styles, genres and media are superior to others – extends at least as far back as Aristotle. Aesthetic categories have always been difficult to maintain, but they have been particularly fluid during the past fifty years in the United States. What does it mean to undercut the prestige of high art with popular culture? What happens to art and society when the boundaries separating high and low art are gone – when Proust and Porky Pig rub shoulders and the museum resembles the supermarket? This course examines fiction, painting and film during a roughly ten-year period (1964-1975) in which reigning cultural hierarchies disintegrated and older terms like “high culture” and “mass culture” began to lose their meaning. In the first unit, we will approach the death of the high art novel in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, which disrupts notions of literature through a superficial suburban American landscape and through the form of the novel itself. The second unit turns to Andy Warhol and Pop Art, which critics consider either an American avant-garde movement undermining high art or an unabashed celebration of vacuous consumer culture. In the third unit, we will turn our attention to The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the rise of cult films in the 1970s. Throughout the semester, we will engage art criticism, philosophy and sociology to help us make sense of important concepts that bear upon the status of art in modern society: tradition, craftsmanship, community, allusion, protest, authority and aura. -

Andy Warhol Was Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928 and Died in Manhattan in 1987

ANDY WARHOL Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928 and died in Manhattan in 1987. He attended free art classes offered at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh at a young age. In 1945, after graduating high school, he enrolled at the Carnegie Institute for Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), focused his studies on pictorial design, and graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1949. Shortly after, Warhol moved to New York City to pursue a career in commercial art. In the late 1950s, Warhol redirected his attention to painting, and famously debuted “pop art”. In 1964, Warhol opened “The Factory”, which functioned as an art studio, and became a cultural hub for famous socialites and celebrities. Warhol’s work has been presented at major institutions and is featured in innumerous prominent collections worldwide. ANDY WARHOL B. 1928, D. 1987 LIVED AND WORKED IN NEW YORK, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Andy Warhol: Self Portrait (Fright Wigs), Skarstedt Upper East Side, New York (NY) The Age of Ambiguity: Abstract Figuration, Figurative Abstraction, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St Moritz (Switzerland) 2016 Andy Warhol - Idolized, David Benrimon Fine Art, New York (NY) Andy Warhol - Shadows, Yuz Museum Shanghai (Shanghai) Andy Warhol: Sunset, The Menil Collection, Houston, TX Andy Warhol: Contact - M. Woods Beijing (China) Andy Warhol: Portraits, Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, CA) Andy Warhol: Works from the Hall Collection, Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, England) Warhol: Royal, Moco Museum (Amsterdam, Netherlands) I‘ll be your mirror. Screen Tests von Andy Warhol, Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst (GfZK) (Leipzig, Germany) Andy Warhol: Icons - The Fralin Museum of Art, University of Virginia Art Museums (Charlottesville, VA) Andy Warhol - Little Electric Chairs, Venus Over Manhattan (New York City, NY) Andy Warhol - Shadows, Honor Fraser (Los Angeles, CA) Andy Warhol - Artist Rooms, Firstsite (Colchester, UK) Andy Warhol Portraits, Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, CA) Andy Warhol. -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

Warhol's Aesthetics Jonathan Flatley Wayne State University, [email protected]

Criticism Volume 56 Article 1 Issue 3 Andy Warhol 2014 Warhol's Aesthetics Jonathan Flatley Wayne State University, [email protected] Anthony E. Grudin University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism Recommended Citation Flatley, Jonathan and Grudin, Anthony E. (2014) "Warhol's Aesthetics," Criticism: Vol. 56: Iss. 3, Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/criticism/vol56/iss3/1 INTRODUCTION: WARHOL’S AESTHETICS Jonathan Flatley and Anthony E. Grudin often we can glimpse the worlds proposed and prom- ised by queerness in the realm of the aesthetic. —José Muñoz, Cruising utopia (2009)1 The essays in this volume show an Andy Warhol who was deeply engaged in the aesthetic, if we understand that word in its ancient Greek sense to refer to “the whole region of human perception and sensation,” as Terry Eagleton put it.2 Warhol, these essays propose, was fascinated by the ways in which the human sensorium was interfacing with new technologies of reproduction and mediation—indeed, with the vast set of processes that characterize mid-twentieth-century modernity in the United States (commodification, urbanization, the expansion of mass cul- ture and its audiences, and the mass production of everything from food to cars and music) and the new object and image world created by these processes: “comics, picnic tables, men’s trousers, celebrities, shower cur- tains, refrigerators, Coke bottles—all the great modern things that the Abstract Expressionists -

Book Preview: End Section

and elaborating on older uses of queer camp per- personal, and political and cultural arenas that formance, the film contains a much greater came to underscore the very phenomenon of gay degree of sentimentality about, and admiration liberation. Evoking a spirit of ‘stranger sociabil- for, the many things it stages and indeed dresses. ity’, to borrow a term from Michael Warner, the Much more extensively developed as a form of film advances the construction of new kinds of live theatre, camp performance in the late ’60s social formation, by elaborating on experiences BIBLIOGRAPHY and early ’70s was very much about bringing par- and feelings that many male-desiring men had in ticipants into the fold of new kinds of social, cul- common, though could not always easily share in tural and political spaces, where the values a collective context due to the prohibitions and assigned to things in everyday life could be inven- anxieties of a repressive society. !' tively challenged and given new life and meaning Just as the film potently and provocatively through their re-configuration. addresses the audience through its complex Camp in Pink Narcissus is also an integral combination of the sexually direct and the polit- part of what might be described as the film’s ically sharp, it also, more simply, offers audi- world-making ethos. The film repeatedly uses ences the sheer pleasure of viewing, for its own camp to garner a feeling for the pleasure of sake, a glistening, endlessly unfolding display of gay male experiences of socialising, if not col- light, colour, texture and movement. -

Andy Warhol's Exploding Plastic Inevitable

Jean Wainwright Mediated Pain: Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable ‘Warhol has indeed put together a total environment. But it is an assemblage that actually vibrates with menace, cynicism and perversion. To experience it is to be brutalized, helpless…The Flowers of Evil are in full bloom with the Exploding, Plastic, Inevitable’.1 The ‘Exploding Plastic Inevitable’ (EPI) was Andy Warhol’s only foray into a total inter-media experience.2 From 1966 to 1967 the EPI, at its most developed, included up to three film projectors3, sometimes with colour reels projected over black and white, variable speed strobes, movable spots with coloured gels, hand-held pistol lights, mirror balls, slide projectors with patterned images and, at its heart, a deafening live performance by The Velvet Underground.4 Gerard Malanga’s dancing – with whips, luminous coloured tape and accompanied by Mary Woronov or Ingrid Superstar – completed the assault on the senses. [Fig.9.1] This essay argues that these multisensory stimuli were an arena for Warhol to mediate an otherwise internalised interest in pain, using his associates and the public as baffles to insulate himself from it. His management of the EPI allowed Warhol to witness both real and simulated pain, in a variety of forms. These ranged from the often extreme reactions of the viewing audience to the repetition on his background reels, projected over the foreground action.5 Warhol had adopted passivity as a self-fashioning device.6 This was a coping mechanism against being hurt, and a buffer to shield his emotional self from the public gaze.7 At the same time it became an effective manipulative device, deployed upon his Factory staff. -

Fly Me to the Moon 50 Jahre Mondlandung / 50 Years On

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Moon museum Weddigen, Tristan Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-170401 Book Section Published Version Originally published at: Weddigen, Tristan (2019). Moon museum. In: Hug, Cathérine. Fly me to the moon. 50 Jahre Mondlan- dung. Köln: Snoeck Verlagsgesellschaft, 54-61. Fly me to the Moon 50 Jahre Mondlandung / Cathérine Hug 50 years on Mit Beiträgen von / With texts by James Attlee D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem Walter Famler Liam Gillick Cathérine Hug Ulrich Köhler Kunsthaus Tristan Weddigen Zürich Museum der Moderne Salzburg Inhalt / Contents 3 7 Grußwort / Welcome note Christoph Becker 9 Vorwort / Foreword Thorsten Sadowsky 13 Vorwort / Foreword Cathérine Hug 17 Fly me to the Moon — and back! (Eine Einleitung) James Attlee 29 Der Mond ist eine Welt wie diese hier Ulrich Köhler 35 Ein gewaltiger Sprung — auch für die Planetengeologie Walter Famler 43 Asche auf dem Mond. Vorläufige Gedanken zur ikonografischen Dialektik von Astronauten und Kosmonauten Liam Gillick 49 Herrliche Trostlosigkeit Tristan Weddigen 55 Moon Museum D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem 63 Schwester Mond: Ein lunares Gedicht in X Strophen Gedichte und Exzerpte vom 19. Jahrhundert 71 bis in die Gegenwart Isaac Asimov Clemens Berger Richard Buckminster Fuller Emily Dickinson Friedrich Dürrenmatt Michael Fehr Robert Gernhardt Durs Grünbein Mae C. Jemison Primo Levi Norman Mailer Sylvia Plath Sun Ra Tracy K. Smith 5 English texts and translations Cathérine Hug 289 Fly me to the Moon — and back! (An introduction) James Attlee 301 The Moon is a world like this Ulrich Köhler 307 A huge leap - also for planetary geology Walter Famler 313 Ashes on the Moon. -

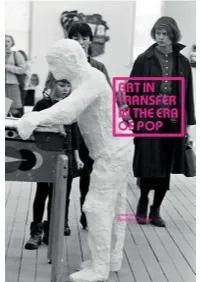

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Andy at a Sell out of a Closed Shoe Warehouse in the Late 1970S

AndyUaMt PI OFFICIAL EXHIBITION CATALOGUE Reed Fine Art Gallery University of Maine at Presque Isle September 5 – October 11, 2008 Generous sponsorship for this exhibition from the Presque Isle Savings Bank of Maine. A special thank you to our UMPI arts alumna, JANE CAULFIELD, owner of Morning Star Art & Framing of Presque Isle. The University of Maine at Presque Isle is grateful for their support. COVER IMAGE : “Shoe, (Women’s Single) 1980” Polaroid Unless otherwise noted, all images © Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Catalogue by Linda Zillman, M.A., History of Photography; Design & Layout: Dick Harrison The Warhol Photographs The Owl Undated 5” x 7” black and white print It is sheer luck that we received this photo, UMPI’s owl mascot, from the Warhol Foundation. We have made the pairing of The Owl and The Pussycat in honor of Edward Lear’s poem and with the thought that it is just the kind of association Warhol would have made. In 1978 Martha Graham created a dance entitled The Owl and the Pussycat using the words from Lear’s famous poem. Rudolph Nureyev danced and Liza Minnelli was the narrator. The Owl and the Pussycat played at Covent Garden and in New York City. ( Diaries, p. 229-230) Andy was present at the Covent Garden opening on July 23, 1979. ( Diaries, p. 230) Both The Owl and The Pussycat share the same white background as well as interesting shadows in the photographs. Not exactly dancing “by the light of the moon,” as Lear wrote, but use your imagination! The Warhol Photographs The Pussycat Undated 5” x 7” black and white print In 1976, Andy Warhol did an acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas portrait of a cat. -

Who Was Andy Warhol? Ebook, Epub

WHO WAS ANDY WARHOL? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kirsten Anderson,Tim Salamunic,Nancy Harrison,Greg Copeland,Gregory Copeland | 112 pages | 26 Dec 2014 | Grosset & Dunlap | 9780448482422 | English | United States Who Was Andy Warhol? PDF Book The facial features and hair are screen-printed in black over the orange background. Warhol moved to New York right after college and worked there for a decade as a commercial illustrator. He founded the gossip magazine Interview , a stage for celebrities he "endorsed" and a business staffed by his friends. Many of his creations are very collectible and highly valuable. Up-tight: the Velvet Underground story. Born Andrew Warhola to poor Slovakian immigrants in the steel-producing city of Pittsburgh in , Warhol's chances of making it in the art world were slim. On February 20, , he was admitted to New York Hospital where his gallbladder was successfully removed and he seemed to be recovering. Warhol spoke to this apparent contradiction between his life and work in his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol , writing that "making money is art and working is art, and good business is the best art. All of these films, including the later Andy Warhol's Dracula and Andy Warhol's Frankenstein , were far more mainstream than anything Warhol as a director had attempted. Warhol also loved to go to movies and started a collection of celebrity memorabilia, particularly autographed photos. Kunstmuseum Wolfsbug, Andy Warhol October Files. March 31, Watch and learn more. His most popular and critically successful film was Chelsea Girls In , Warhol turned his attention to the pop art movement, which began in Britain in the mids. -

Robert Indiana

ROBERT INDIANA BORN IN NEW CASTLE, INDIANA 1928 DIED IN VINALHAVEN, MAINE 2018 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 “Robert Indiana: A Legacy of Love,” McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX “LOVE Is in the Air,” Galerie Gmurzynska, New York, NY 2019 “Robert Indiana,” Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY “Robert Indiana: The Richmond Connection,” Richmond Art Museum, Richmond, IN 2018 “Robert Indiana,” Kasmin Gallery, New York, NY “Robert Indiana LOVE Long,” Asia Society, Hong Kong “Robert Indiana: A Sculpture Retrospective,” Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY and Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, FL “Love & Peace: Robert Indiana Memorial Exhibition,” Contemporary Art Foundation, Tokyo, Japan 2017 "Robert Indiana: One Through Zero,” Glass House, New Canaan, CT "Robert Indiana,” Pinacoteca Comunale Casa Rusca, Locarno, Switzerland 2016 "Robert Indiana,” Galleria d'Arte Maggiore G.A.M, Bologna, Italy 2015 "Robert Indiana: Sign Paintings 1960-65,” Craig F Starr Gallery, New York, NY "AMOR by Robert Indiana,” Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA 2014 “Robert Indiana’s Hartley Elegies,” McNay Art Museun, San Antonio, TX “Robert Indiana: The Mother of Us All,” McNay Art Museun, San Antonio, TX “Celebrating Love!”, Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, ME “The Essential Robert Indiana,” Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN 2013 “Indiana by the Numbers,” Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN “The Monumental Woods,” Galerie Gmurzynska, Zurich, Switzerland “Robert Indiana: Decade Autoportrait,” de Sarthe Gallery, Hong Kong “Robert Indiana: Beyond LOVE,”