Warhol's Hustler and Queen Assembly Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexion Q 2-3

www.ExpressGayNews.com • April 22, 2002 Q1 CYMK COVER STORY Miami Gay and Lesbian Film Festival Highlights By Mary Damiano Treading Water, The Fourth Annual Miami Gay & Thursday, May 2, 7pm Lesbian Film Festival is back, with lots of Casey is in exile from her well-to-do film, premieres, panels and, of course, parties. Catholic family, living just across the bay The festival runs from April 26-May 5, and (but worlds apart) from their pristine will showcase feature films, documentaries, waterfront home, in a tiny house boat that shorts, presentations and panels that will she shares with her girlfriend Alex. But when entertain, inform and excite the expected Christmas rolls around, familial duty calls, audience of 15,000. and even the black sheep must make an All films will be shown at the Colony appearance. Director Lauren Himmel will Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami, except attend the screening. A South Florida the opening and closing night films. premiere. Tickets to the film and the post- Here are some highlights of this year’s screening Reel Women reception are $20. film offerings: The Cockettes Tuesday, April 30 7pm An east coast premiere, this film captures The Cockettes, the legendary drag- musical theater phenomenon, and the rarified air of the free-love, acid-dropping, gender- Ruthie and Connie: Every Room in the House Circuit Saturday April 27, 2:30pm bending hippie capital of San Francisco they inhabited in the late 1960s. Features Sylvester Friday, May 3, 9:30pm If Dorothy and Blanche on The Golden Sugar Sweet Dirk Shafer’s hallucinatory new film finds Girls had ever (finally) come out, they’d Saturday, April 27, 9:30pm and Divine, who both appear in the film, along with other notable witnesses to history, such the soul of the circuit and seeks redemption be Ruthie and Connie, the real-life same- Naomi makes lesbian porn. -

HUSTLER HOLLYWOOD Real Estate Press Kit

HUSTLER HOLLYWOOD Real Estate Press Kit http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Presentation Overview Hustler Hollywood Overview Real Estate Criteria Store Portfolio Testimonials http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Company History Hustler Hollywood The vision to diversify the Hustler brand and enter the mainstream retail market was realized in 1998 when the first Hustler Hollywood store opened on the iconic Sunset Strip in West Hollywood, CA. Larry Flynt's innovative formula for retailing immediately garnered attention, resulting in coverage in Allure and Cosmopolitan magazines as well as periodic appearances on E! Entertainment Network, the HBO series Entourage and Sex and the City. Since that time Hustler Hollywood has expanded to 25 locations nationwide ranging in size from 3,200 to 15,000 square feet. Hustler Hollywood showcases fashion-forward, provocative apparel and intimates, jewelry, home décor, souvenirs, novelties, and gifts; all in an open floor plan, contemporary design and lighting, vibrant colors, custom fixtures, and entirely viewable from outside through floor to ceiling windows. http://www.hustlerhollywoodstores.com Phone: +1(323) 651-5400 X 7698 | e-mail: [email protected] Retail Stores Hustler Hollywood, although now mimicked by a handful of competitors, has stood distinctly apart from peers by offering consumers, particularly couples, a refreshing bright welcoming store to shop in. Each of the 25 stores are well lit and immaculately clean, reflecting a creative effort to showcase a fun but comfortable atmosphere in every detail of design, fixture placement, and product assortment. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

Andy Warhol From

Andy Warhol From “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” 8 February - 9 March 2019 I. Andy Warhol “Dancing Sprites”, ca. 1953 ink and watercolor on paper 73.7 x 29.5 cm (framed: 92.7 x 48.4 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/23 Andy Warhol “Sprite Acrobats”, ca. 1956 ink on paper, double-sided 58.5 x 73.5 cm (framed: 92.4 x 77.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/08 Andy Warhol “Sprite Figures Kissing”, ca. 1951 graphite on paper 14.3 x 21.6 cm (framed: 32.2 x 39.5 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1951/01 Warhol used this motif in several illustrations from the early 1950s: for an anonymous article entitled “Romantic Possession” (publication unknown, c. 1950) and for Weare Holbrook’s “Women – What To Do With Them”, Park East (March 1952), p. 26. See Paul Maréchal, Andy Warhol: The Complete Commissioned Magazine Work, 1948- 1987: A Catalogue Raisonné (Munich: Prestel, 2014), pp. 30, 50. Andy Warhol “Female Sprite”, ca. 1954 graphite on paper, double-sided 27.9 x 21.6 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1954/05 Andy Warhol “Sprite Head with Feet”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.9 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/24 Andy Warhol “Sprite Portrait with Shoes”, ca. 1953 ink on paper 27.8 x 21.5 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1953/25 II. Andy Warhol “The House That Went To Town”, 1952-1953 graphite, ink and tempera on paper 27.7 x 21.7 cm (framed: 46 x 39.7 x 2.8 cm) AW/P 1956/25 The likely prototype for Warhol and Corkie’s “THE HOUSE THAT went to TOWN” is Virginia Lee Burton’s celebrated children’s book The Little House, first published in 1942. -

War Prevention Works 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict by Dylan Mathews War Prevention OXFORD • RESEARCH • Groupworks 50 Stories of People Resolving Conflict

OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP war prevention works 50 stories of people resolving conflict by Dylan Mathews war prevention works OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP 50 stories of people resolving conflict Oxford Research Group is a small independent team of Oxford Research Group was Written and researched by researchers and support staff concentrating on nuclear established in 1982. It is a public Dylan Mathews company limited by guarantee with weapons decision-making and the prevention of war. Produced by charitable status, governed by a We aim to assist in the building of a more secure world Scilla Elworthy Board of Directors and supported with Robin McAfee without nuclear weapons and to promote non-violent by a Council of Advisers. The and Simone Schaupp solutions to conflict. Group enjoys a strong reputation Design and illustrations by for objective and effective Paul V Vernon Our work involves: We bring policy-makers – senior research, and attracts the support • Researching how policy government officials, the military, of foundations, charities and The front and back cover features the painting ‘Lightness in Dark’ scientists, weapons designers and private individuals, many of decisions are made and who from a series of nine paintings by makes them. strategists – together with Quaker origin, in Britain, Gabrielle Rifkind • Promoting accountability independent experts Europe and the and transparency. to develop ways In this United States. It • Providing information on current past the new millennium, has no political OXFORD • RESEARCH • GROUP decisions so that public debate obstacles to human beings are faced with affiliations. can take place. nuclear challenges of planetary survival 51 Plantation Road, • Fostering dialogue between disarmament. -

Outrageous Opinion, Democratic Deliberation, and Hustler Magazine V

VOLUME 103 JANUARY 1990 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONCEPT OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE: OUTRAGEOUS OPINION, DEMOCRATIC DELIBERATION, AND HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL Robert C. Post TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL ........................................... 6o5 A. The Background of the Case ............................................. 6o6 B. The Supreme Court Opinion ............................................. 612 C. The Significance of the Falwell Opinion: Civility and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ..................................................... 616 11. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE ............................. 626 A. Public Discourse and Community ........................................ 627 B. The Structure of Public Discourse ............... ..................... 633 C. The Nature of Critical Interaction Within Public Discourse ................. 638 D. The First Amendment, Community, and Public Discourse ................... 644 Im. PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND THE FALIWELL OPINION .............................. 646 A. The "Outrageousness" Standard .......................................... 646 B. The Distinction Between Speech and Its Motivation ........................ 647 C. The Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................... 649 i. Some Contemporary Understandings of the Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................................................ 650 (a) Rhetorical Hyperbole ............................................. 650 (b) -

Robinson, Jack (1928-1997) by Dan Oppenheimer ; Claude J

Robinson, Jack (1928-1997) by Dan Oppenheimer ; Claude J. Summers Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Jack Robinson as a Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com young man. Image provided by The Jack Mississippi-born photographer Jack Robinson came to prominence in the 1960s as a Robinson Archive. Image courtesy Jack result of the stunning fashion and celebrity photographs he shot for such magazines as Robinson Archive. Vogue and Vanity Fair. He created striking images of the era's cultural icons, Image Copyright © Jack particularly young actors, artists, and musicians as diverse as Peter Allen, Warren Robinson Archive. Beatty, Richard Chamberlain, Joe Dallesandro, Clint Eastwood, Elton John, Liza Minnelli, Melba Moore, Jack Nicholson, Nina Simone, Sonny and Cher, Michael Tilson Thomas, Lily Tomlin, Tina and Ike Turner, Andy Warhol, and The Who, among many others. Robinson captured the particular feel and spirit of the tumultuous 1960s, but by 1972 he was burned out, himself a victim of the era's excesses. Having reached the pinnacle of his profession, he abruptly retreated from New York to pursue a quieter life in Memphis. After 1972, he took no more photographs, though he found a creative outlet in the design of stained glass windows. Jack Uther Robinson, Jr. was born in Meridian, Mississippi on September 18, 1928 to Jack Robinson, Sr. and Euline Jones Robinson. He grew up in Clarksdale, Mississippi, the literal heart of the Mississippi Delta, an area famous for racial injustice, the Blues, and social and religious conservatism. His father was a mechanic and auto parts dealer. -

The Chadron-Chicago 1000-Mile Cowboy Race

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: The Chadron-Chicago 1,000-Mile Cowboy Race Full Citation: William E Deahl, Jr., “The Chadron-Chicago 1,000-Mile Cowboy Race,” Nebraska History 53 (1972): 166-193. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1972Chadron_Race.pdf Date: 6/22/2011 Article Summary: Horse racing was a popular sport of the American West. As preparations were made for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, with its emphasis upon American accomplishments and customs, it was not surprising that someone suggested a horse race from the West to Chicago. The ride was designed to pit skilled Western horsemen against each other over a one thousand-mile route spanning the three states of Nebraska, Iowa and Illinois. This article presents the planning, the promotion, the opposition, and the story of the actual race. Cataloging Information: Names: A C Putnam, N H Weir, William -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Wednesday, December 18, 2019 NEW YORK DOYLE+DESIGN® MODERN and CONTEMPORARY ART and DESIGN

Wednesday, December 18, 2019 NEW YORK DOYLE+DESIGN® MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART AND DESIGN AUCTION Wednesday, December 18, 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, December 14, 10am – 5pm Sunday, December 15, Noon – 5pm Monday, December 16, 11am – 6pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalog: $25 THE ESTATE OF SYLVIA MILES Doyle is honored to offer artwork and It was Miles’ association with Andy Miles’ Central Park South apartment, memorabilia from the Estate of Sylvia Warhol as a close friend and one of which she occupied from 1968 until her Miles (1924-2019). Twice nominated the so-called “Warhol Superstars” that death earlier this year, was filled with for an Academy Award, Miles is best cemented her status as a New York icon. memorabilia from her career and artwork PAINTINGS, SCULPTURE, remembered for her strong performances Miles had a starring role in Warhol’s gifted by her talented group of friends, in diverse works ranging from Midnight 1972 film Heat, the third in a trilogy that particularly Warhol. Cowboy to Sex and the City, as a bona parodied Sunset Boulevard, alongside PHOTOGRAPHS & PRINTS fide “Warhol Superstar,” and as a Joe Dallesandro. Property from the Estate of Sylvia Miles prominent and frequent figure on comprises lots 18, 21, 34-36, 62-65, 67, the Manhattan party scene. 73, 90, 99, 102, 103, 105, 127-131, 144, 146, 166. INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATES OF CONTENTS Elsie Adler Paintings 1-155 Evelyn Berezin Prints 156-171 Arthur Brandt Furniture & Decorative Arts 172-253 Miriam Diner Silver 254-270 Steven R. -

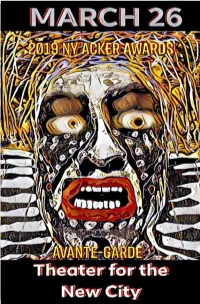

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary.