04-14-2018 Luisa Miller Mat.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libretto Nabucco.Indd

Nabucco Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI major partner main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie al sostegno e la collaborazione di Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Sindaco di Parma Pietro Vignali Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Vincenzo Bernazzoli Paolo Cavalieri Alberto Chiesi Francesco Luisi Maurizio Marchetti Carlo Salvatori Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore Musicale Yuri Temirkanov Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini Nabucco Dramma lirico in quattro parti su libretto di Temistocle Solera dal dramma Nabuchodonosor di Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois e Francis Cornu e dal ballo Nabucodonosor di Antonio Cortesi Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Mesopotamia, Tavoletta con scrittura cuneiforme La trama dell’opera Parte prima - Gerusalemme All’interno del tempio di Gerusalemme, i Leviti e il popolo lamen- tano la triste sorte degli Ebrei, sconfitti dal re di Babilonia Nabucco, alle porte della città. Il gran pontefice Zaccaria rincuora la sua gente. In mano ebrea è tenuta come ostaggio la figlia di Nabucco, Fenena, la cui custodia Zaccaria affida a Ismaele, nipote del re di Gerusalemme. Questi, tuttavia, promette alla giovane di restituirle la libertà, perché un giorno a Babilonia egli stesso, prigioniero, era stato liberato da Fe- nena. I due innamorati stanno organizzando la fuga, quando giunge nel tempio Abigaille, supposta figlia di Nabucco, a comando di una schiera di Babilonesi. Anch’essa è innamorata di Ismaele e minaccia Fenena di riferire al padre che ella ha tentato di fuggire con uno stra- niero; infine si dichiara disposta a tacere a patto che Ismaele rinunci alla giovane. -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Reseña De" Giacomo Puccini: the Great Opera Collection" De Renata

Pensamiento y Cultura ISSN: 0123-0999 [email protected] Universidad de La Sabana Colombia Visbal-Sierra, Ricardo Reseña de "Giacomo Puccini: The Great Opera Collection" de Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi, Mario del Monaco, Giulietta Simionato, et al. Pensamiento y Cultura, vol. 12, núm. 1, junio, 2009, pp. 229-231 Universidad de La Sabana Cundinamarca, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=70111758015 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Reseñas va, sin embargo, con este encuentro el protagonista toma Giacomo Puccini: la decisión de abandonar la inmersión en el bajo mundo, en el cual no encuentra una verdadera misión en su vida, The Great Opera Collection pues comprende que la lucha violenta no transformará el mundo, sino todo lo contrario, ayudará más al caos a los (La Bohème, Tosca, Madama Butterfly, Manon Lescaut, La fan- países en vías de desarrollo. ciulla del West, Turandot, Il Trittico: Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, Gianni Schicchi). El otro personaje con mucha más vitalidad en Buda Blues es Sebastián, un trotamundos que no se puede que- Intérpretes principales: Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi, dar quieto en un solo lugar y busca su propia identidad Mario del Monaco, Giulietta Simionato, et al. a través de los viajes. Por eso, al inicio de la novela se en- 15 discos compactos cuentra en Kinshasa y, por amistad con Vicente, empieza a Decca 4759385 divagar sobre “La Organización” en el Congo. -

PACO164 Front.Std

[Q]oi© □ PACO 164 DIGITAL AUDIO Beecham ,..;., PACO 164 ., Puccini: La Boheme '\, , , This 1956 recording of Lo Boheme continues to stand out in the catalogue. Soloists and conductor combined to create a classic of recorded opera oozing with musicality. This remarkable achievement occurred -despite the cast and conductor having little rehearsa l time or previous col laborations to fa ll back on. This was the only time PabYm~(!_t\ Beecham and Bjiirling worked together, and while Bjiirling and de los Angeles had recorded Pogliocci in 1953 and I ,, \ appeared in four performances of Faust at the Metropolitan the same year, they never sang in a performance of Lo Boheme on the same stage. ,~ Rodolfo was Jussi Bjiirling's most frequent stage role (with 114 performances) and it lasted the longest in his repertoire (1934-1960). In an opera packed with memorable tunes Rodolfo has many of them and Bjiirling's truly \ beautiful voice captures the poetic tenderness of the exchanges with Mimi in act one before easing into the rodolfo Jussi bjorling .. lyricism needed for the aria and closing duet. As someone not particularly renowned for his stage acting, it is to our ) benefit that Bjiirling does all his acting with his voice. As the tragedy of Mimi's illness unfolds Bjiirling is able to mimi victoria de los angeles expose Rodolfo's despair simply via his vocal timbre and co louring. On ly the hard-hearted can listen to act four marcello robert merrill ~ · without a tear and those who persist in thinking as Bjiirling as a 'cold' singer are surely disproved by this display of true Italianate style. -

MICHAEL FINNISSY at 70 the PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’S College, London

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2016). Michael Finnissy at 70: The piano music (9). This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17520/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MICHAEL FINNISSY AT 70 THE PIANO MUSIC (9) IAN PACE – Piano Recital at Deptford Town Hall, Goldsmith’s College, London Thursday December 1st, 2016, 6:00 pm The event will begin with a discussion between Michael Finnissy and Ian Pace on the Verdi Transcriptions. MICHAEL FINNISSY Verdi Transcriptions Books 1-4 (1972-2005) 6:15 pm Books 1 and 2: Book 1 I. Aria: ‘Sciagurata! a questo lido ricercai l’amante infido!’, Oberto (Act 2) II. Trio: ‘Bella speranza in vero’, Un giorno di regno (Act 1) III. Chorus: ‘Il maledetto non ha fratelli’, Nabucco (Part 2) IV. -

Verdi, Moffo, Bergonzi, Verrett, Macneil, Tozzi

Verdi Luisa Miller mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Luisa Miller Country: Italy Released: 1965 Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1127 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1383 mb WMA version RAR size: 1667 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 183 Other Formats: WMA DXD DTS MP2 MMF ASF AU Tracklist A1 Overture A2 Act I (Part I) B Act I (Concluded) C Act II (Part I) D Act II (Concluded) E Act III (Part I) F Act III (Concluded) Credits Baritone Vocals [Miller] – Cornell MacNeil Bass Vocals [Count Walter] – Giorgio Tozzi Bass Vocals [Wurm] – Ezio Flagello Chorus – RCA Italiana Opera Chorus Chorus Master – Nino Antonellini Chorus Master [Assistant] – Giuseppe Piccillo Composed By – Verdi* Conductor – Fausto Cleva Conductor [Assistant] – Fernando Cavaniglia, Luigi Ricci Engineer – Anthony Salvatore Libretto By – Salvatore Cammarano Libretto By [Translation] – William Weaver* Liner Notes – Francis Robinson Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Federica] – Shirley Verrett Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Laura] – Gabriella Carturan Orchestra – RCA Italiana Opera Orchestra Producer – Richard Mohr Soprano Vocals [Luisa] – Anna Moffo Sound Designer [Stereophonic Stage Manager] – Peter F. Bonelli Tenor Vocals [A Peasant] – Piero De Palma Tenor Vocals [Rodolfo] – Carlo Bergonzi Notes Issued with 40-page booklet containing credits, liner notes, photographs and libretto in Italian with English translation Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Verdi*, Moffo*, Verdi*, Moffo*, Bergonzi*, Verrett*, Bergonzi*, MacNeil*, Tozzi*, Verrett*, -

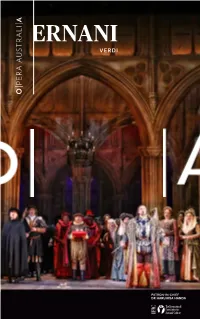

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

2110520Fb Tuscany

NAXOS HIGH-DEFINITION AUDIO DISC This unique programme is the first time that all the ballet music from Verdi’s operas has been brought together 24-bit, 96 kHz Stereo and Surround recordings in a single recording. Although The Four Seasons from I vespri siciliani (The Sicilian Vespers) and the ballet scenes from Aida and Otello have survived, substantial pieces from Il trovatore and Don Carlo are more often cut, while the ballet from Jérusalem is all but unknown. José Serebrier’s recordings with the Bournemouth VERDI: Symphony have resulted in some great successes with unusual repertoire. This release will be of interest both to opera enthusiasts and to those eager to explore Verdi’s neglected and relatively small body of concert music. Giuseppe VERDI the Operas Complete Ballet Music from (1813-1901) Complete Ballet Music from the Operas 1 From Otello: Act III, Scene 7 5:34 2-4 From Macbeth: Act III, Scene 1 10:12 5-8 From Jérusalem: Act III, Scene 1 21:33 9 From Don Carlo: Act III, Scene 2 16:39 0 From Aida: Act I, Scene 2 2:24 VERDI ! From Aida: Act II, Scene 1 1:38 @ From Aida: Act II, Scene 2 4:46 #-% From Il trovatore: Act III, Scene 1 5:56 ^-( From Il trovatore: Act III, Scene 2 17:07 Complete Ballet Music )-£ From I vespri siciliani: Act III, Scene 2 29:25 Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra from the Operas José Serebrier A detailed track list can be found on page 2 of the booklet Bournemouth Recorded at The Lighthouse, Poole, Dorset, UK, from 15th to 17th May, 2011 Produced, engineered and edited by Phil Rowlands • Assistant engineer: Patrick Phillips Symphony Orchestra Booklet notes: José Serebrier • Cover: Set design for Verdi’s Aida by Alfred Roller (1864-1935) With many thanks to Mr Paul Underwood for supporting this recording Special thanks to Clark McAlister, Editor, Kalmus Music Publishers and to Helen Harris, Librarian, BSO ൿ & Ꭿ 2012 Naxos Rights International Ltd • Booklet notes in English • Made in Germany José Serebrier DTS and the DTS-HD Master Audio Logo are the trade-marks of Digital Theater Systems, Inc. -

BRAD DALTON Stage Director [email protected] Cell 310-621-9575

BRAD DALTON Stage Director [email protected] cell 310-621-9575 www.braddalton.com OPERA A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Lyric Opera of Chicago*, Los Angeles Opera*, Carnegie Hall*, (design: Brad Dalton) the Barbican in London*, Opera San Jose (*with Renee Fleming) A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Washington National Opera, San Diego Opera, (design: Michael Yeargan) Austin Lyric Opera A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Hawaii Opera Theatre, Grand Rapids Opera, Townsend Opera, (design: Steven Kemp) Fresno Opera CINDERELLA (American premiere) Packard Humanities Institute, California Theatre ALBERT HERRING Shepherd School of Music, Rice University LA BOHEME Opera Santa Barbara RIGOLETTO Opera San Jose, Opera Santa Barbara THE FLYING DUTCHMAN Opera San Jose TOSCA Opera San Jose THE MAGIC FLUTE Opera San Jose MADAMA BUTTERFLY Opera San Jose IL TROVATORE Opera San Jose FAUST Opera San Jose IDOMENEO Opera San Jose ANNA KARENINA Opera San Jose COSI FAN TUTTE Opera San Jose ROMEO AND JULIET Hawaii Opera Theatre CAVALLERIA/PAGLIACCI New Orleans Opera DON GIOVANNI New Orleans Opera CARMEN New Orleans Opera ALCESTE Opera Boston LA CLEMENZA DI TITO Opera Boston REVIVALS DEAD MAN WALKING State Opera of South Australia (Joe Mantello production) - Winner 2004 Helpmann Award “Best direction of an Opera” THE BARBER OF SEVILLE Metropolitan Opera (John Cox production) IL TROVATORE San Francisco Opera (Nicholas Muni production) RIGOLETTO San Francisco Opera (Mark Lamos production) THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO San Francisco Opera (John Copley production) THE BARBER OF SEVILLE San Francisco