Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..180 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 15.00)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 165 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, October 19, 2012 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 11221 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, October 19, 2012 The House met at 10 a.m. terrorism and because it is an unnecessary and inappropriate infringement on Canadians' civil liberties. New Democrats believe that Bill S-7 violates the most basic civil liberties and human rights, specifically the right to remain silent and the right not to be Prayers imprisoned without first having a fair trial. According to these principles, the power of the state should never be used against an individual to force a person to testify against GOVERNMENT ORDERS himself or herself. However, the Supreme Court recognized the Ï (1005) constitutionality of hearings. We believe that the Criminal Code already contains the necessary provisions for investigating those who [English] are involved in criminal activity and for detaining anyone who may COMBATING TERRORISM ACT present an immediate threat to Canadians. The House resumed from October 17 consideration of the motion We believe that terrorism should not be fought with legislative that Bill S-7, An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Canada measures, but rather with intelligence efforts and appropriate police Evidence Act and the Security of Information Act, be read the action. In that context one must ensure that the intelligence services second time and referred to a committee. and the police forces have the appropriate resources to do their jobs. -

Core 1..182 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 14.00)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 044 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, November 4, 2011 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 2961 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, November 4, 2011 The House met at 10 a.m. Mr. Chris Alexander: Mr. Speaker, I rise again in support of the bill that addresses the urgent need to ensure the proper functioning of our military justice system. Prayers The bill comes to us in the context of two facts that I think all hon. members will recognize. One, a legal circumstance that places GOVERNMENT ORDERS additional pressure on all of us to ensure the smooth functioning of our military justice system, one that has served Canada well for Ï (1005) decades. We just celebrated the centenary of the Office of the Judge Advocate General without a challenge to its constitutionality. I will [English] come back to that issue and delve into the circumstances that have SECURITY OF TENURE OF MILITARY JUDGES ACT led to a danger of that happening. Hon. Bev Oda (for the Minister of National Defence) moved that Bill C-16, An Act to amend the National Defence Act (military judges), be read the second time and referred to a committee. This is a measure that has been considered in the House three times during three previous Parliament when bills were brought Mr. Chris Alexander (Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister forward that provided for exactly the very limited measures that are of National Defence, CPC): Mr. -

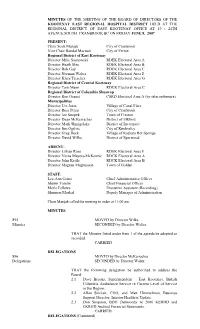

Minutes of the Meeting of The

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE KOOTENAY EAST REGIONAL HOSPITAL DISTRICT HELD AT THE REGIONAL DISTRICT OF EAST KOOTENAY OFFICE AT 19 - 24TH AVENUE SOUTH CRANBROOK BC ON FRIDAY MAY 6, 2011 PRESENT Chair John Kettle RDCK Electoral Area B Regional District of East Kootenay Director Mike Sosnowski Electoral Area A Director Heath Slee Electoral Area B Director Rob Gay Electoral Area C Director Jane Walter Electoral Area E Director Wendy Booth Electoral Area F Director Gerry Wilkie Electoral Area G Regional District of Central Kootenay Director Garry Jackman RDCK Electoral Area A Director Larry Binks RDCK Electoral Area C Columbia Shuswap Regional District Director Ron Oszust (by telephone) CSRD Electoral Area A Municipalities Director Ute Juras Village of Canal Flats Alternate Director Angus Davis City of Cranbrook Director Liz Schatschneider City of Cranbrook Director Ron Toyota Town of Creston Director Dean McKerracher District of Elkford Director Cindy Corrigan City of Fernie Director Gerry Taft District of Invermere Director Jim Ogilvie City of Kimberley Director Magnus Magnusson (by telephone) Town of Golden Director Dee Conklin Village of Radium Hot Springs Director David Wilks District of Sparwood ABSENT Director Scott Manjak City of Cranbrook STAFF Lee-Ann Crane CAO / Corporate Officer Shannon Moskal Deputy Corporate Officer Shawn Tomlin Chief Financial Officer Tina Hlushak Executive Assistant (Recording Secretary) Chair John Kettle called the meeting to order at 11:01 am. ADDITION OF LATE ITEMS 1064 MOVED by Director Kettle Late items SECONDED by Director McKerracher THAT the following late item for the agenda under New Business be approved: - Health Connection BC Partnership Agreement CARRIED ADOPTION OF AGENDA 1065 MOVED by Director Gay Agenda SECONDED by Director Binks THAT the agenda for the KERHD Board of Directors meeting be adopted as amended. -

Edmonton—Spruce Grove Alberta Conservative 6801-170Th Street (Main Office) Edmonton, Alberta T544W4 [email protected]

Ambrose, Rona (Hon.) Edmonton—Spruce Grove Alberta Conservative 6801-170th Street (Main Office) Edmonton, Alberta T544W4 [email protected] Anders, Rob Calgary West Alberta Conservative 11 Spruce Centre SW Calgary, Alberta T3C 3B3 [email protected] [email protected] Benoit, Leon Vegreville—Wainwright Alberta Conservative 5004-49th Street, Professional Bldg, PO Box 300 Mannville, Alberta T0B 2W0 [email protected] Calkins, Blaine Wetaskiwin Alberta Conservative 5 - 4612 50th St, (Main Office) Ponoka, Alberta T4J 1S7 [email protected] Crockatt, Joan Calgary Centre Alberta Conservative 1333 8th Street SW, Suite 333 Calgary, Alberta T2R 1M6 [email protected] Dreeshen, Earl Red Deer Alberta Conservative 4315 55th Avenue, Suite 100A (Main Office) Red Deer, Alberta T4N 4N7 [email protected] Duncan, Linda Edmonton—Strathcona Alberta NDP 10049-81st Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T6E 1W7 [email protected] Goldring, Peter Edmonton East Alberta Independent Conservative 9111 - 118 Avenue NW, - Edmonton, Alberta T5B 0T9 [email protected] Harper, Stephen (Right Hon.) Calgary Southwest Alberta Conservative 1600 - 90th Avenue SW, Suite A-203 Calgary, Alberta T2V 5A8 [email protected] Hawn, Laurie (Hon.) Edmonton Centre Alberta Conservative 11156 142nd Street (Main Office) Edmonton, Alberta T5M 4G5 [email protected] Hillyer, Jim Lethbridge Alberta Conservative 255 - 8th Street South (Main Office) Lethbridge, Alberta T1J 4Y1 [email protected] Jean, Brian Fort McMurray—Athabasca Alberta Conservative -

Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Board Of

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE KOOTENAY EAST REGIONAL HOSPITAL DISTRICT HELD AT THE REGIONAL DISTRICT OF EAST KOOTENAY OFFICE AT 19 - 24TH AVENUE SOUTH CRANBROOK BC ON FRIDAY JUNE 8, 2007 PRESENT: Chair Scott Manjak City of Cranbrook Vice Chair Randal Macnair City of Fernie Regional District of East Kootenay Director Mike Sosnowski RDEK Electoral Area A Director Heath Slee RDEK Electoral Area B Director Rob Gay RDEK Electoral Area C Director Norman Walter RDEK Electoral Area E Director Klara Trescher RDEK Electoral Area G Regional District of Central Kootenay Director Tom Mann RDCK Electoral Area C Regional District of Columbia Shuswap Director Ron Oszust CSRD Electoral Area A (by teleconference) Municipalities Director Ute Juras Village of Canal Flats Director Ross Priest City of Cranbrook Director Joe Snopek Town of Creston Director Dean McKerracher District of Elkford Director Mark Shmigelsky District of Invermere Director Jim Ogilvie City of Kimberley Director Greg Deck Village of Radium Hot Springs Director David Wilks District of Sparwood ABSENT: Director Lillian Rose RDEK Electoral Area F Director Verna Mayers-McKenzie RDCK Electoral Area A Director John Kettle RDCK Electoral Area B Director Magnus Magnusson Town of Golden STAFF: Lee-Ann Crane Chief Administrative Officer Shawn Tomlin Chief Financial Officer Merle Fellows Executive Assistant (Recording) Shannon Moskal Deputy Manager of Administration Chair Manjak called the meeting to order at 11:00 am. MINUTES 895 MOVED by Director Wilks Minutes SECONDED by Director Walter THAT the Minutes listed under Item 1 of the agenda be adopted as recorded. CARRIED DELEGATIONS 896 MOVED by Director McKerracher Delegations SECONDED by Director Walter THAT the following delegation be authorized to address the Board: 2.1 Dave Brooks, Superintendent – East Kootenay, British Columbia Ambulance Service re Current Level of Service in the Region. -

Together Now Revelstoke As a Diverse & Welcoming Mountain Community

all together now Revelstoke as a diverse & welcoming mountain community October 2015 Resources, events and information about immigrant settlement and diversity appreciation in Revelstoke Pam & Satwant tutoring session. Become an ESL tutor! See page 3 Content click event for information p. 2 Election day is October 19 p. 2 Learn English with Fresh off the Boat p. 3 Become an ESL tutor Women’s History Month p. 3 Carousel of Nations 2016 needs you 4 Last day of Sukkot Jewish p. 4 Author discussion “letters from the land of fear” p. 4 Film from Argentina 12 Thanksgiving Day National Holiday 15 Muharram/Islamic New Year Muslim editorial contact: Jill Pratt [email protected] / 30 Halloween 250-837-4235 ext. 6502 Knitting at the Library Are you an immigrant living in Revelstoke? Bring your needlework & craft projects Revelstoke Settlement Services provide Every Tuesday until April 26 English practice groups, English tutoring, Information 6:45pm to 8:30pm about living in Canada, workshops & social events Okanagan Regional Library, Visit us at the Revelstoke Branch WCG WorkBC Employment Services Centre. 605 Campbell Avenue 117 Campbell Avenue Wednesdays 1pm-3pm (at the Community Centre) Or our main location at 1401 West 1st Street (Okanagan College) Jill Pratt 250-837-4235 ext. 6502 Yarn & needles available for immigrants [email protected] contact Revelstoke Settlement Services ww.okanagan.bc.ca/settlement Election day is Monday October 19th Revelstoke is in the Kootenay-Columbia electoral Candidates in this district district Bill Green—Green Party of Canada Advance voting takes place October 9-October 12. Don Johnston—Liberal Party of Canada Wayne Stetski—New Democratic Party Find out if you are registered to vote: David Wilks—Conservative Party of Canada call 1-800-463-6868 or use the online voter registration service www.elections.ca Want to improve your English in a fun, casual setting with others? Last year we watched the TV show Friends and learned about culture, slang and pronunciation. -

41St GENERAL ELECTION 41 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE

www.elections.ca CANDIDATES ELECTED / CANDIDATS ÉLUS a Se n n A col ol R Lin inc ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED e L ELECTORAL DISTRICT PARTY ELECTED CANDIDATE ELECTED C er d O T S M CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU C I bia C D um CIRCONSCRIPTION PARTI ÉLU CANDIDAT ÉLU É ol A O N C C t C A Aler 35050 Mississauga South / Mississauga-Sud Stella Ambler N E H !( A A N L T e 35051 Mississauga—Streetsville Brad Butt R S E 41st GENERAL ELECTION C I B 41 ÉLECTION GÉNÉRALE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR 35052 Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre T I A Q S Phillip TERRE-NEUVE-ET-LABRADOR 35053 Newmarket—Aurora Lois Brown U H I s In May 2, 2011 E T L 2mai,2011 35054 Niagara Falls Hon. / L'hon. Rob Nicholson E - É 10001 Avalon Scott Andrews B E 35055 Niagara West—Glanbrook Dean Allison A 10002 Bonavista—Gander—Grand Falls—Windsor Scott Simms I N Niagara-Ouest—Glanbrook I Z E 10003 Humber—St. Barbe—Baie Verte Hon. / L'hon. Gerry Byrne L R N D 35056 Nickel Belt Claude Gravelle a E A n 10004 Labrador Peter Penashue N L se 35057 Nipissing—Timiskaming Jay Aspin N l n E e S A o d E 10005 Random—Burin—St. George's Judy Foote E D P n und ely F n Gre 35058 Northumberland—Quinte West Rick Norlock E e t a L s S i a R U h AXEL 10006 St. John's East / St. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Directors of The

MINUTES OF THE REGIONAL DISTRICT OF EAST KOOTENAY GOVERNANCE & REGIONAL SERVICES COMMITTEE MEETING HELD AT THE REGIONAL DISTRICT OFFICE IN CRANBROOK BC ON NOVEMBER 8, 2018 PRESENT Chair Rob Gay Electoral Area C Director Mike Sosnowski Electoral Area A Director Stan Doehle Electoral Area B Director Jane Walter Electoral Area E Director Susan Clovechok Electoral Area F Director Gerry Wilkie Electoral Area G Director Lee Pratt City of Cranbrook Director Wesly Graham City of Cranbrook Director Ange Qualizza City of Fernie Director Don McCormick City of Kimberley Director Dean McKerracher District of Elkford Director Allen Miller District of Invermere Director David Wilks District of Sparwood Director Karl Sterzer Village of Canal Flats Director Clara Reinhardt Village of Radium Hot Springs STAFF Shawn Tomlin Chief Administrative Officer Shannon Moskal Corporate Officer Connie Thom Executive Assistant (Recording Secretary) Chair Rob Gay called the meeting to order at 3:30 pm. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA MOVED by Director Pratt Agenda SECONDED by Director Sosnowski THAT the agenda for the Governance & Regional Services Committee meeting be adopted. CARRIED ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES MOVED by Director McKerracher Minutes SECONDED by Director Graham THAT the Minutes of the Governance & Regional Services Committee meeting held on October 4, 2018 be adopted as circulated. CARRIED NEW BUSINESS 48110 MOVED by Director Doehle Wayne Stetski, MP SECONDED by Director Wilkie Request for Topics THAT the following topics be submitted to Wayne Stetski, MP Kootenay Columbia, for an update at an upcoming Board of Directors meeting: • bill C-71 gun control • temporary foreign workers program • navigable waters legislation-restoration of lost protections • Columbia River Treaty • Kootenay National Park emergency services upgrades CARRIED 48111 MOVED by Director Reinhardt Cheque Register SECONDED by Director McKerracher THAT the cheque register for the RDEK General Account for October 2018 in the amount of $2,078,529.66 be approved as paid. -

Minister of Mental Health and Addictions

Fifh Session, 41st Parliament OFFICIAL REPORT OF DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday, July 29, 2020 Afernoon Sitting Issue No. 351 THE HONOURABLE DARRYL PLECAS, SPEAKER ISSN 1499-2175 PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Entered Confederation July 20, 1871) LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR Her Honour the Honourable Janet Austin, OBC Fifth Session, 41st Parliament SPEAKER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Honourable Darryl Plecas EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Premier and President of the Executive Council ............................................................................................................... Hon. John Horgan Deputy Premier and Minister of Finance............................................................................................................................Hon. Carole James Minister of Advanced Education, Skills and Training..................................................................................................... Hon. Melanie Mark Minister of Agriculture.........................................................................................................................................................Hon. Lana Popham Attorney General.................................................................................................................................................................Hon. David Eby, QC Minister of Children and Family Development ............................................................................................................ Hon. Katrine Conroy Minister of State for Child Care......................................................................................................................................Hon. -

2011 Annual Report

Southern Interior DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE TRUST Southern Interior DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE TRUST SOUTHERN INTERIOR DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE TRUST ANNUAL REPORT 2011 About the Southern Interior Development Initiative Trust Annual Report This report covers the Southern Interior Development Initiative Trust (SIDIT) for the period April 1, 2010 through March 31, 2011. The report was prepared for our stakeholders, the British Columbia Provincial Government, and reflects SIDIT’s commitment to support economic development in the Southern Interior. Southern Interior Development Initiative Trust #204, 3131 29th Street Vernon, British Columbia V1T 5A8 PHONE 250-545-6829 FAX 250-545-6896 SOUTHERN INTERIOR DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE TRUST ANNUAL REPORT 2011 2 What’s Inside Message from the Chair 4 Board of Directors 5 An Overview of SIDIT 7 Funding Partners 10 Investment in Education 12 Communications and Networking 13 Economic Impact 14 Demonstrating Best Practices 15 Report on Investments 16 Job Creation 17 Funding by Investment Sector 18 Funding by Region 19 Our Future Direction 20 Meet some of our Clients 21 Financial Statements 26 SOUTHERN INTERIOR DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE TRUST ANNUAL REPORT 2011 3 Message from the Chair – June 2011 The Southern Interior Development Initiative Trust adding $113.16 million to regional GDP; stimulating the (SIDIT) was established in February 2006 with an initial creation of 1,552 sustainable jobs; facilitating $24.3 million capitalization of $50 million and a mandate to stimulate in annual revenues to regional businesses; and feeding and facilitate the realization of positive, long lasting and back in excess of $13.7 million/year in tax dollars to Canada measurable benefits within the southern interior of British and $3.3 million/year to British Columbia. -

Board of Directors Meeting

Board of Directors Meeting November 7, 2014 9:00 am AMENDED AGENDA VOTING: Unless otherwise indicated on this agenda, all Directors have one vote and a simple majority is required for a motion to pass. Who Votes Count 1. Call to Order 1.1 Introduction: Andy Christie, Building Inspector 2. Addition of Late Items 3. Adoption of the Agenda 4. Adoption of the Minutes 4.1 October 3, 2014 Meeting 5. Delegations and Invited Presentations 6. Correspondence 6.1 Central East Kootenay Community Directed Funds Committee Meeting Minutes of October 16, 2014 6.2 Columbia Valley Community Directed Funds Committee Meeting Minutes of October 27, 2014 6.3 Elk Valley Community Directed Funds Committee Meeting Minutes of October 17, 2014 6.4 Forest Practices Board – 2013/2014 Annual Report 6.5 Southern Interior Beetle Action Coalition – Beetle Bites and Working to Advanced Rural Development in Southern Interior Report 6.6 E-Comm 9-1-1 – Quarterly Newsletter 6.7 BC Transit – Transit Promotes Newsletter 6.8 Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Management Plan for the Westslope Cutthroat Trout 6.9 Judy DeJong – Fraggle Rock 6.10 Fred Stevens, Volunteer Appreciation Dinner – Letter of Thanks 6.11 Cranbrook & District Community Foundation – Letter of Thanks 6.12 National Aboriginal Economic Development Board – Letter of Thanks 6.13 Township of Spallumcheen – Concerns Regarding Smart Meters Amended Agenda Page 2 Board of Directors November 7, 2014 Correspondence (continued) 6.14 Christina Lake Stewardship Society – Prevent Invasion of Zebra and Quagga Mussels 6.15 Minister -

Core 1..116 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 16.25)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 147 Ï NUMBER 074 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, April 11, 2014 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 4557 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, April 11, 2014 The House met at 10 a.m. monetary and regulatory challenges were all part of his deep humanity and decency. He gave his all to serve a country he loved. Prayers As he said just three weeks ago when he departed as the minister of finance, “We live in the greatest country in the world, and I want Canadians to know that it has been my honour and my privilege to Ï (1005) serve them.” [English] HON. JIM FLAHERTY Despite his unwavering commitment to public service, Jim never The Deputy Speaker: To honour the memory of our late lost sight of what was truly important. He loved his family, he loved colleague, I understand there have been discussions among his hometown of Whitby, and he loved to kick back with a tall glass representatives of all parties in the House to have some members of Guinness as often as he could. make statements to pay tribute to him. Hon. K. Kellie Leitch (Minister of Labour and Minister of Jim never forgot the humble working class roots that were Status of Women, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I ask everyone to pause and established at the dinner table with his family in Lachine, Quebec. In look at their dictionary this morning. Under “Irish” they will see a fact, while attending Princeton, and later earning a law degree, Jim leprechaun with a twinkle in his eyes and fierce determination bussed tables in cafeterias and drove a cab.