Swiss Consensus Recommendations on Urinary Tract Infections in Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PATHOLOGY of the RENAL SYSTEM”, I Hope You Guys Like It

ﺑﺴﻢ اﷲ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﻦ اﻟﺮﺣﯿﻢ ھﺬه اﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة ﻋﺒﺎرة ﻋﻦ إﻋﺎدة ﺗﻨﺴﯿﻖ وإﺿﺎﻓﺔ ﻧﻮﺗﺎت وﻣﻮاﺿﯿﻊ ﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة زﻣﻼﺋﻨﺎ ﻣﻦ اﻟﺪﻓﻌﺔ اﻟﺴﺎﺑﻘﺔ ٤٢٧ اﻷﻋﺰاء.. ﻟﺘﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻣﻊ اﻟﻤﻨﮭﺞ اﻟﻤﻘﺮر ﻣﻦ اﻟﻘﺴﻢ ﺣﺮﺻﻨﺎ ﻓﯿﮭﺎ ﻋﻠﻰ إﻋﺎدة ﺻﯿﺎﻏﺔ ﻛﺜﯿﺮ ﻣﻦ اﻟﺠﻤﻞ ﻟﺘﻜﻮن ﺳﮭﻠﺔ اﻟﻔﮭﻢ وﺳﻠﺴﺔ إن ﺷﺎء اﷲ.. وﺿﻔﻨﺎ ﺑﻌﺾ اﻟﻨﻮﺗﺎت اﻟﻤﮭﻤﺔ وأﺿﻔﻨﺎ ﻣﻮاﺿﯿﻊ ﻣﻮﺟﻮدة ﺑﺎﻟـ curriculum ﺗﻌﺪﯾﻞ ٤٢٨ ﻋﻠﻰ اﻟﻤﺬﻛﺮة ﺑﻮاﺳﻄﺔ اﺧﻮاﻧﻜﻢ: ﻓﺎرس اﻟﻌﺒﺪي ﺑﻼل ﻣﺮوة ﻣﺤﻤﺪ اﻟﺼﻮﯾﺎن أﺣﻤﺪ اﻟﺴﯿﺪ ﺣﺴﻦ اﻟﻌﻨﺰي ﻧﺘﻤﻨﻰ ﻣﻨﮭﺎ اﻟﻔﺎﺋﺪة ﻗﺪر اﻟﻤﺴﺘﻄﺎع، وﻻ ﺗﻨﺴﻮﻧﺎ ﻣﻦ دﻋﻮاﺗﻜﻢ ! 2 After hours, or maybe days, of working hard, WE “THE PATHOLOGY TEAM” are proud to present “PATHOLOGY OF THE RENAL SYSTEM”, I hope you guys like it . Plz give us your prayers. Credits: 1st part = written by Assem “ THe AWesOme” KAlAnTAn revised by A.Z.K 2nd part = written by TMA revised by A.Z.K د.ﺧﺎﻟﺪ اﻟﻘﺮﻧﻲ 3rd part = written by Abo Malik revised by 4th part = written by A.Z.K revised by Assem “ THe AWesOme” KAlAnTAn 5th part = written by The Dude revised by TMA figures were provided by A.Z.K Page styling and figure embedding by: If u find any error, or u want to share any idea then plz, feel free to msg me [email protected] 3 Table of Contents Topic page THE NEPHROTIC SYNDROME 4 Minimal Change Disease 5 MEMBRANOUS GLOMERULONEPHRITIS 7 FOCAL SEGMENTAL GLOMERULOSCLEROSIS 9 MEMBRANOPROLIFERATIVE GLOMERULONEPHRITIS 11 DIABETIC NEPHROPATHY (new) 14 NEPHRITIC SYNDROME 18 Acute Post-infectious GN 19 IgA Nephropathy (Berger Disease) 20 Crescentic GN 22 Chronic GN 24 SLE Nephropathy (new) 26 Allograft rejection of the transplanted kidney (new) 27 Urinary Tract OBSTRUCTION, 28 RENAL STONES 23 HYDRONEPHROSIS -

RENAL BIOPSY and GLOMERULONEPHRITIS by J

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.35.409.604 on 1 November 1959. Downloaded from 604 RENAL BIOPSY AND GLOMERULONEPHRITIS By J. H. Ross, M.D., M.R.C.P. Senior Medical Registrar, The Connaught Hospital, and Assistant, The Mledical Unit, The London Hospital Introduction sufficient to establish a diagnosis in a few condi- Safe methods of percutaneous renal biopsy were tions such as amyloid disease and diabetic first described by Perez Ara (1950) and Iversen glomerulosclerosis, but cortex with at least io and Brun (I95I) who used aspiration techniques. glomeruli is necessary for an accurate assessment Many different methods have since been described; of the renal structure; occasionally, up to 40 the simplest is that of Kark and Muehrcke (1954) glomeruli may be present in a single specimen. who use the Franklin modification of the Vim- The revelation of gross structural changes in Silverman needle. the kidneys of patients who can be recognized Brun and Raaschou (1958) have recently re- clinically as having chronic glomerulonephritis is viewed the majority of publications concerned of little value and does not contribute to manage- with renal biopsy and have concluded that the risk ment or prognosis. In contrast, biopsy specimensProtected by copyright. to the patients is slight. They mentioned three from patients in the early stages of glomerulo- fatalities which have been reported but considered nephritis, particularly those who have developed that, in each case, death was probably due to the the nephrotic syndrome insidiously without disease process rather than the investigation. haematuria or renal failure or who showy no Retroperitoneal haematomata have been recorded evidence of disease other than proteinuria, may in patients with hypertension or uraemia but are provide useful information. -

Guidelines on Urolithiasis

Guidelines on Urolithiasis C. Türk (chair), T. Knoll (vice-chair), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, A. Skolarikos, M. Straub, C. Seitz © European Association of Urology 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. METHODOLOGY 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Data identification 7 1.3 Evidence sources 7 1.4 Level of evidence and grade of recommendation 7 1.5 Publication history 8 1.5.2 Potential conflict of interest statement 8 1.6 References 8 2. CLASSIFICATION OF STONES 9 2.1 Stone size 9 2.2 Stone location 9 2.3 X-ray characteristics 9 2.4 Aetiology of stone formation 9 2.5 Stone composition 9 2.6 Risk groups for stone formation 10 2.7 References 11 3. DIAGNOSIS 12 3.1 Diagnostic imaging 12 3.1.1 Evaluation of patients with acute flank pain 12 3.1.2 Evaluation of patients for whom further treatment of renal stones is planned 13 3.1.3 References 13 3.2 Diagnostics - metabolism-related 14 3.2.1 Basic laboratory analysis - non-emergency urolithiasis patients 15 3.2.2 Analysis of stone composition 15 3.3 References 16 4. TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH RENAL COLIC 16 4.1 Renal colic 16 4.1.1 Pain relief 16 4.1.2 Prevention of recurrent renal colic 16 4.1.3 Recommendations for analgesia during renal colic 17 4.1.4 References 17 4.2 Management of sepsis in obstructed kidney 18 4.2.1 Decompression 18 4.2.2 Further measures 18 4.2.3 References 18 5. STONE RELIEF 19 5.1 Observation of ureteral stones 19 5.1.1 Stone-passage rates 19 5.2 Observation of kidney stones 19 5.3 Medical expulsive therapy (MET) 20 5.3.1 Medical agents 20 5.3.2 Factors affecting success of medical expulsive -

Guidelines on Urolithiasis

GUIDELINES ON UROLITHIASIS (Text update April 2010) Ch. Türk (chairman), T. Knoll (vice-chairman), A. Petrik, K. Sarica, C. Seitz, M. Straub, O. Traxer Eur Urol 2001 Oct;40(4):362-71 Eur Urol 2007 Dec;52(6):1610-31 J Urol 2007 Dec;178(6):2418-34 Methodology This update is based on the 2008 version of the Urolithiasis guidelines produced by the former guidelines panel. Literature searches were carried out in Medline and Embase for ran- domised control trials and systematic reviews published between January 1st, 2008, and November 30, 2009, and sig- nificant differences in diagnosis and treatment or in evidence level were considered. Introduction Urinary stone disease continues to occupy an important place in everyday urological practice. The average lifetime risk of stone formation has been reported in the range of 5-10%. Recurrent stone formation is a common problem with all types of stones and therefore an important part of the medical care of patients with stone disease. Classification and Risk Factors Different categories of stone formers can be identified based Urolithiasis 251 on the chemical composition of the stone and the severity of the disease (Table 1). Special attention must be given to those patients who are at high risk of recurrent stone formation (Table 2). Table 1: Categories of stone formers Stone composition Category Non-calcium Infection stones: INF stones Magnesium ammonium phosphate Ammonium urate Uric acid UR Sodium urate Cystine CY Calcium First time stone former, without residual So stones stone or stone fragments. First time stone former, with residual Sres stone or stone fragments. -

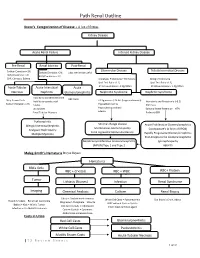

Path Renal Outline

Path Renal Outline Krane’s Categorization of Disease + A lot of Extras Kidney Disease Acute Renal Failure Intrinsic Kidney Disease Pre‐Renal Renal Intrinsic Post‐Renal Sodium Excretion <1% Glomerular Disease Tubulointerstitial Disease Sodium Excretion < 1% Sodium Excretion >2% Labs aren’t that useful BUN/Creatinine > 20 BUN/Creatinine < 10 CHF, Cirrhosis, Edema Urinalysis: Proteinuria + Hematuria Benign Proteinuria Spot Test Ratio >1.5, Spot Test Ratio <1.5, Acute Tubular Acute Interstitial Acute 24 Urine contains > 2.0g/24hrs 24 Urine contains < 1.0g/24hrs Necrosis Nephritis Glomerulonephritis Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritic Syndrome Inability to concentrate Urine RBC Casts Dirty Brown Casts Inability to secrete acid >3.5g protein / 24 hrs (huge proteinuria) Hematuria and Proteinuria (<3.5) Sodium Excretion >2% Edema Hypoalbuminemia RBC Casts Hypercholesterolemia Leukocytes Salt and Water Retention = HTN Focal Tubular Necrosis Edema Reduced GFR Pyelonephritis Minimal change disease Allergic Interstitial Nephritis Acute Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Membranous Glomerulopathy Analgesic Nephropathy Goodpasture’s (a form of RPGN) Focal segmental Glomerulosclerosis Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis Multiple Myeloma Post‐Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis IgA nephropathy (MPGN) Type 1 and Type 2 Alport’s Meleg‐Smith’s Hematuria Break Down Hematuria RBCs Only RBC + Crystals RBC + WBC RBC+ Protein Tumor Lithiasis (Stones) Infection Renal Syndrome Imaging Chemical Analysis Culture Renal Biopsy Calcium -

Factors in the Cause of Death in Carcinoma of the Cervix

FACTORS IN THE CAUSE OF DEATH IN CARCINOMA OF THE CERVIX A STUDY OF FIFTy-SEVEN CASES COMING TO NECROPSY B]ARNE PEARSON, M.D. (Prom the Cancer Institute and De;artment 01 Pathology, University of Minnesota Medkal School, Minneapolis ) This study is based upon 57 consecutive cases of carcinoma Qf the cervix in which autopsy examinations were performed. Thirty-one of these were studied at the University Hospitals. The remaining 26 were taken from the autopsy records in the Department of Pathology at the University of Minne sota. Microscopic sections were studied except in a few instances in which they could not be obtained. An attempt has been made to determine the im mediate lethal factors and the frequency with which they occur. No attempt is made to determine the efficacy of the treatment. URETERAL STRICTURE Stricture of the ureters with consequent hydronephrosis and hydroureters was the most striking and constant autopsy finding in this series of cases, being present in 42 cases, or 75 per cent. This is in accord with the observations of others. Ernst Holzbach in 4& carcinomas of the cervix coming to autopsy found 31 bilateral and 10 unilateral strictures. Sampson found that the fac tors responsible for strictures were external pressure of a mass of carcinoma around the ureters as a result of parametrial extension and lymphatic metasta sis, and added infection and edema. Carson states that metastasis may occur to the lymphatics of the ureters. Constriction by metastatic processes was not, however, very common in our series. It occurred only three times and was located in the midportion of the ureter. -

Silent Hydronephrosis/Pyonephrosis Due to Upper Urinary Tract Calculi in Spinal Cord Injury Patients

Spinal Cord (2000) 38, 661 ± 668 ã 2000 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/sc Silent hydronephrosis/pyonephrosis due to upper urinary tract calculi in spinal cord injury patients S Vaidyanathan*,1, G Singh1, BM Soni1, P Hughes2, JWH Watt1, S Dundas3, P Sett1 and KF Parsons4 1Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 2Department of Radiology, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 3Department of Cellular Pathology, District General Hospital, Southport, Merseyside, UK; 4Department of Urology, Royal Liverpool University Hospital, Liverpool, UK Study design: A study of four patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) in whom a diagnosis of hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis was delayed since these patients did not manifest the traditional signs and symptoms. Objectives: To learn from these cases as to what steps should be taken to prevent any delay in the diagnosis and treatment of hydronephrosis/pyonephrosis in SCI patients. Setting: Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, Southport, UK. Methods: A retrospective review of cases of hydronephrosis or pyonephrosis due to renal/ ureteric calculus in SCI patients between 1994 and 1999, in whom there was a delay in diagnosis. Results: A T-5 paraplegic patient had two episodes of urinary tract infection (UTI) which were successfully treated with antibiotics. When he developed UTI again, an intravenous urography (IVU) was performed. The IVU revealed a non-visualised kidney and a renal pelvic calculus. In a T-6 paraplegic patient, the classical symptom of ¯ank pain was absent, and the symptoms of sweating and increased spasms were attributed to a syrinx. -

Since the Report by Maccalluim,L in I905, of Parathyroid Adenoma

ENLARGEMENT OF THE PARATHYROID GL.NDS IN RENAL DISEASE* A. M. PAPPENEIKER, M.D., ASiD S. L. WnyNs, M.D. (From Ike Department of Pathology, College of Physiciaxs axd Surgeons, Columbia Uxiversity, Newz York, N.Y.) The initial impetus to this study was given by a case of typical osteitis fibrosa with adenomatous enlargement of three parathyroid glands and associated polycystic kidneys.t The question which arose in the discussion was in regard to the relation between the kidney disease, obviously congenital in origin, and the parathyroid enlargement. Since the report by MacCalluim,l in I905, of parathyroid adenoma associated with chronic glomerulonephritis, the simultaneous occur- rence of renal lesions with parathyroid tumors or enlargement has been noted repeatedly. This association has been emphasized par- ticularly in the recent study of Albright, Baird, Cope and Bloom- berg,2 who collected 83 cases of hyperparathyroidism, 43 of which showed some type of renal damage. The renal lesions are attributed to the precpitation of calcium in the tubules, with resultant sclero- sis, contraction and insufficiency, or to the formation of calculi in the pelvis associated with pyelonephritis. Thus, these authors in general regard the renal lesions as a sequel to the chronic hyperparathyroidism and stress especially the de- position of calcium in the renal tissue as the proximate cause of the kidney lesions. However, in their discussion they raise the question as to whether the parathyroid enlargement may not be secondary to the renal disease in the cases in which multiple glands are affected. They report: "It seems conceivable that a chronic renal insuf- ficiency with phosphate retention and a high inorganic phosphorus level might likewise cause hyperplasia of all parathyroid tissue which might go on to multiple tumor formation... -

Lessons Learned

Prevention and Reversal of Chronic Disease Copyright © 2019 RN Kostoff PREVENTION AND REVERSAL OF CHRONIC DISEASE: LESSONS LEARNED By Ronald N. Kostoff, Ph.D., School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology 13500 Tallyrand Way, Gainesville, VA, 20155 [email protected] KEYWORDS Chronic disease prevention; chronic disease reversal; chronic kidney disease; Alzheimer’s Disease; peripheral neuropathy; peripheral arterial disease; contributing factors; treatments; biomarkers; literature-based discovery; text mining ABSTRACT For a decade, our research group has been developing protocols to prevent and reverse chronic diseases. The present monograph outlines the lessons we have learned from both conducting the studies and identifying common patterns in the results. The main product of our studies is a five-step treatment protocol to reverse any chronic disease, based on the following systemic medical principle: at the present time, removal of cause is a necessary, but not necessarily sufficient, condition for restorative treatment to be effective. Implementation of the five-step treatment protocol is as follows: FIVE-STEP TREATMENT PROTOCOL TO REVERSE ANY CHRONIC DISEASE Step 1: Obtain a detailed medical and habit/exposure history from the patient. Step 2: Administer written and clinical performance and behavioral tests to assess the severity of symptoms and performance measures. Step 3: Administer laboratory tests (blood, urine, imaging, etc) Step 4: Eliminate ongoing contributing factors to the chronic disease Step 5: Implement treatments for the chronic disease This individually-tailored chronic disease treatment protocol can be implemented with the data available in the biomedical literature now. It is general and applicable to any chronic disease that has an associated substantial research literature (with the possible exceptions of individuals with strong genetic predispositions to the disease in question or who have suffered irreversible damage from the disease). -

Review Paper Renal Allotransplantation

« Review Paper Eur. Urol. 8: 61-73 (1982) Renal Allotransplantation José M. Gil- Vernet Department of Urology, Barcelona University School of Medicine, Barcelona, Spain Key Words. Renal autotransplant • Extracorporeal surgery Abstract. The progress of renal transplantation has made possible the development of autotransplant and extracor- poreal surgery. This has allowed us to find a new tactical solution to those cases in which conservative conventional surgery was impossible or useless, including those cases where the only solution used to be nephrectomy or high urinary diversion. In other cases such as surgery of renovascular hypertension, its application has allowed us to obtain a greater percentage of cures with fewer risks for the patient. Although we must admit that this operation has been abused, in the last few years its indications have increased due to the good results obtained. The fewer complications and absence of mortality demonstrate that autotransplantation is a good solution and has undoubtedly increased our surgical possibilities. Concept History In an orthodox way, renal autotransplantation means In 1902 Ullmann [1] and Carrel [2] experimentally achieved the first successful renal autotransplantation, moving the kidney of a dog to section the kidney from the vascular pedicle and excre- from its lumbar fossa to its neck, in this way laying the foundations tory tract so as to reimplant it into a different vascular for future human renal homotransplantation. But the experience territory of the same individual. Therefore it must not be obtained in allotransplantation, based on the progress in the fields of confused with renal transposition which is the sectioning organ conservation (hypothermy), has made possible the develop- of the vascular pedicle only, but not of the ureter, with ment of autotransplantation. -

Following Article. 9. Hydronephrosis and Pyonephrosis. 2I. Malignant Growth. of the Haemorrhage, but the Possibility of a Vesica

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.10.103.190 on 1 May 1934. Downloaded from 190 POST-GRADUATE MEDICAL JOURNAL May, 1934. THE CAUSES AND DIAGNOSTIC IMPORTANCE OF HAEMATURIA IN SURGICAL CONDITIONS. By W. K. IRWIN, M.D., F.R.C.S., Surgeon to St. Paul's Hospital for Genito-Urinary Diseases. The early recognition and consequent appropriate treatment of the causes of haematuria is of the greatest importance and will, it is hoped, be facilitated by the following article. Blood which is of renal origin is, as a rule, uniformly distributed throughout the urine. Terminal hIematuria, i.e., blood passed mainly at the end of micturition, is usually due to a lesion of the bladder or prostate, while initial hermaturia, i.e., blood appearing at the beginning of urination, usually originates from some part of the urethra. Blood issuing from the meatus independently of micturition as a rule has its source anterior to the compressor urethrae muscle. The surgical causes of haematuria may be classified as follows: RENAL AND URETERIC. I. Growths of the kidney or ureter. 2. Renal tuberculosis. 3. Pyelonephritis. 4. Renal or ureteric calculus. 5. Renal haemorrhage after emptying a distended bladder. by copyright. 6. Injury to the kidney or ureter. 7. Movable kidney. 8. Polycystic kidney. 9. Hydronephrosis and Pyonephrosis. IO. Renal Abscess. VESICAL. II. Papilloma of the bladder. I2. Carcinoma of the bladder. I3. Infection of the bladder. http://pmj.bmj.com/ I4. Vesical calculus. I5. After emptying a distended bladder. PROSTATIC AND VESICULAR. I6. Acute prostatitis. I7. Spermatocystitis. I8. Cancer or senile enlargement of the prostate. -

Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury

Ultrasound in Acute Kidney Injury Pamela Parker Ultrasound Specialty Manager Aims • What is Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)? • Discuss the implications of AKI for USS • Revisit Resistive Index (RIs) Why? The FACTS • AKI is responisble for a 20-30% in-patient mortality rate • The mortality rate varies greatly depending on the severity, setting, and many patient- related factors but it is a KILLER. AKI Explained • The older term is 'acute renal failure' (ARF). • Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a rapid deterioration of renal function, resulting in inability to maintain fluid, electrolyte and acid-base balance. AKI Explained • It is detected and monitored by serial serum creatinine readings primarily, which rise acutely • The definition of acute kidney injury has changed in recent years, and detection is now mostly based on monitoring creatinine levels, with or without urine output. Acute Kidney Injury, adding insult to injury (2009) • 2009 UK National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD) found serious deficiencies in patients who died with a diagnosis of AKI. • Only 50% of patients received good medical care Why NICE? • Acute kidney injury is seen in 13–18% of all people admitted to hospital, with older adults being particularly affected. • The costs to the NHS of acute kidney injury (excluding costs in the community) are estimated to be between £434 million and £620 million per year, • More than the costs associated with breast cancer, or lung and skin cancer combined. Why NICE? • Acute kidney injury: prevention, detection and management of acute kidney injury up to the point of renal replacement therapy • NICE guideline August 2013 Why NICE? • Estimated that improving care could save 12,000 lives in England and save the NHS £150 million per year NICE Guideline 2013 Ultrasound Offer urgent ultrasound of the urinary tract to patients with acute kidney injury who: – have no identified cause of acute kidney injury, or – are at risk of urinary tract obstruction.