Université De Montréal Inuit Ethnobotany in the North American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006)

Plant Phenology Puale Bay 2010 Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006) Stacey E. Pecen U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Peninsula/Becharof NWR, P.O. Box 277, King Salmon, AK 99613 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES Phenology, the timing of major biological events during a plant or animal’s life, can be monitored to detect changes in climate. Major events are called phenophases: leaf emergence, flowering, fruit ripening, and senescing. According to Menzel and Estrella (2001), plant phenology studies have shown that the average growing season is increasing by 0.2 days/year. It is especially important to monitor changes in higher latitudes, such as Alaska, where global warming is expected to occur earlier and at a greater magnitude (Henry and Molau 1997). The Northern Hemisphere (above 40o N) has experienced an increase in temperature of at least 0.5oC/decade from 1966-1995 (Serreze et al. 2000, Euskirchen et al. 2009). Monitoring species abundance and diversity is also vital. Environmental conditions dictate the composition of plant communities. Changes can occur over time, disrupting the balance of these interactions. In a nine year study at Toolik Lake, AK, Chapin et al. (1995) found that species richness declined 30-50% when the mean temperature was increased by 3.5˚C. Forbs and grasses decreased in abundance while woody species, such as Betula spp., increased. Changes in species abundance in regions of the arctic, as a result of warming, were also noted by Euskirchen et al. (2009). -

Ornithocoprophilous Plants of Mount Desert Rock, a Remote Bird-Nesting Island in the Gulf of Maine, U.S.A

RHODORA, Vol. 111, No. 948, pp. 417–447, 2009 E Copyright 2009 by the New England Botanical Club ORNITHOCOPROPHILOUS PLANTS OF MOUNT DESERT ROCK, A REMOTE BIRD-NESTING ISLAND IN THE GULF OF MAINE, U.S.A. NISHANTA RAJAKARUNA Department of Biological Sciences, San Jose´ State University, One Washington Square, San Jose´, CA 95192-0100 e-mail: [email protected] NATHANIEL POPE AND JOSE PEREZ-OROZCO College of the Atlantic, 105 Eden Street, Bar Harbor, ME 04609 TANNER B. HARRIS University of Massachusetts, Fernald Hall, 270 Stockbridge Road, Amherst, MA 01003 ABSTRACT. Plants growing on seabird-nesting islands are uniquely adapted to deal with guano-derived soils high in N and P. Such ornithocoprophilous plants found in isolated, oceanic settings provide useful models for ecological and evolutionary investigations. The current study explored the plants foundon Mount Desert Rock (MDR), a small seabird-nesting, oceanic island 44 km south of Mount Desert Island (MDI), Hancock County, Maine, U.S.A. Twenty-seven species of vascular plants from ten families were recorded. Analyses of guano- derived soils from the rhizosphere of the three most abundant species from bird- 2 nesting sites of MDR showed significantly higher (P , 0.05) NO3 , available P, extractable Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn, and significantly lower Mn compared to soils from the rhizosphere of conspecifics on non-bird nesting coastal bluffs from nearby MDI. Bio-available Pb was several-fold higher in guano soils than for background levels for Maine. Leaf tissue elemental analyses from conspecifics on and off guano soils showed significant differences with respect to N, Ca, K, Mg, Fe, Mn, Zn, and Pb, although trends were not always consistent. -

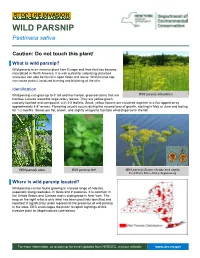

Wild Parsnip Fact Sheet

WILD PARSNIP Pastinaca sativa Caution: Do not touch this plant! ▐ What is wild parsnip? Wild parsnip is an invasive plant from Europe and Asia that has become naturalized in North America. It is well suited for colonizing disturbed areas but can also be found in open fields and lawns. Wild parsnip sap can cause painful, localized burning and blistering of the skin. Identification Wild parsnip can grow up to 5' tall and has hollow, grooved stems that are Wild parsnip infestation hairless. Leaves resemble large celery leaves. They are yellow-green, coarsely toothed and compound, with 3-5 leaflets. Small, yellow flowers are clustered together in a flat-topped array approximately 3-8″ across. Flowering usually occurs during the second year of growth, starting in May or June and lasting for 1-2 months. Seeds are flat, brown, and slightly winged to facilitate wind dispersal in the fall. Wild parsnip stem Wild parsnip leaf Wild parsnip flower cluster and seeds Seed Photo: Bruce Ackley, Bugwood.org ▐ Where is wild parsnip located? Wild parsnip can be found growing in a broad range of habitats, especially along roadsides, in fields and in pastures. It is common in the United States and Canada and is widespread in New York. The map on the right reflects only what has been positively identified and reported; it significantly under represents the presence of wild parsnip in the state. DEC encourages the public to report sightings of this invasive plant to iMapInvasives (see below). For more information, or to sign-up for email updates from NYSDEC, visit our website: www.dec.ny.gov ▐ Why is wild parsnip dangerous? Wild parsnip sap contains chemicals called furanocoumarins which can make skin more vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation. -

New Nomenclature Combinations in the Green Alder Species Complex

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 56:New 1–6 nomenclature(2015) combinations in the green alder species complex (Betulaceae) 1 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.56.5225 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://phytokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research New nomenclature combinations in the green alder species complex (Betulaceae) Joyce Chery1 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 Corresponding author: Joyce Chery ([email protected]) Academic editor: Hugo De Boer | Received 1 May 2015 | Accepted 10 June 2015 | Published 14 August 2015 Citation: Chery J (2015) New nomenclature combinations in the green alder species complex (Betulaceae). PhytoKeys 56: 1–6. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.56.5225 Abstract The name Alnus viridis (Chaix) DC., based on Betula viridis Chaix (1785), has traditionally been attributed to green alders although it is based on a later basionym. Alnus alnobetula (Ehrh.) K. Koch based on Betula alnobetula Ehrh. (1783) is the correct name for green alders. In light of the increasing use and recognition of the name Alnus alnobetula (Ehrh.) K. Koch in the literature. I herein propose new nomenclatural combinations to account for the Japanese and Chinese subspecies respectively: Alnus alnobetula subsp. maximowiczii (Callier ex C.K. Schneid.) J. Chery and Alnus alnobetula subsp. mandschurica (Callier ex C.K. Schneid.) J. Chery. Recent phylogenetic analyses place these two taxa in the green alder species complex, suggesting that they should be treated as infraspecific taxa under the polymorphic Alnus alnobetula. Keywords Green alders, Alnus viridis, Alnus alnobetula, Betulaceae Introduction Characteristic to the genus, Alnus alnobetula (Ehrh.) K. Koch is an anemophilous shrub with carpellate catkins that develop into woody strobili. -

GIANT ULLEUNG CELERY Stephen Barstow1, Malvik, March 2020

GIANT ULLEUNG CELERY 1 Stephen Barstow , Malvik, March 2020 Scientific name: Dystaenia takesimana Carrot family (Apiaceae) English: Seombadi, Sobadi, Dwaejipul, giant Ulleung celery, Korean pig-plant, wild celery, giant Korean celery Korean: 섬바디, 드와지풀 Norwegian: Ulleung kjempeselleri Swedish: Ullungloka, Vulkanloka The genus Dystaenia belongs to the carrot family or umbellifers (Apiaceae) and consists of two perennial species, one is a Japanese endemic (Dystaenia ibukiensis), and the other is endemic to a small island, Ulleung-do in Korea (Dystaenia takesimana). Genetic analysis (Pfosser et al., 2005) suggests that the larger D. takesimana evolved from D. ibukiensis rather than vice versa. The specific epithet takesimana is according to one reference to Takeshima Islet, which is disputed with the Japanese. Campanula takesimana is apparently found there. However, Takeshima island is also an alternative name for Ulleung-do, so this may be a misunderstanding. That Ulleung-do is Takeshima is confirmed on the following web site from the Oki Islands off Japan http://www.oki-geopark.jp/en/flowers-calendar/summer where it is stated that Dystaenia takesimana is also found there and is critically endangered: “This plant was designated as Cultural Property of Ama Town in 2012. It has only been discovered on the two isolated islands of Ama Town of the Oki Islands (Nakanoshima Island) and Ulleung-do Island of South Korea. It can be seen on the Akiya Coast in Nakanoshima Island. It is called Takeshima- shishiudo, as Ulleung-do was referred to as Takeshima” (see the map in Figure 1 for places mentioned here). Ulleung-do is a rocky steep-sided volcanic island some 120 km east of the coast of South Korea, the highest peak reaching 984m. -

Chapter 4 Phytogeography of Northeast Asia

Chapter 4 Phytogeography of Northeast Asia Hong QIAN 1, Pavel KRESTOV 2, Pei-Yun FU 3, Qing-Li WANG 3, Jong-Suk SONG 4 and Christine CHOURMOUZIS 5 1 Research and Collections Center, Illinois State Museum, 1011 East Ash Street, Springfield, IL 62703, USA, e-mail: [email protected]; 2 Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, 690022, Russia, e-mail: [email protected]; 3 Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 417, Shenyang 110015, China; 4 Department of Biological Science, College of Natural Sciences, Andong National University, Andong 760-749, Korea, e-mail: [email protected]; 5 Department of Forest Sciences, University of British Columbia, 3041-2424 mail Mall, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4, Canada, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Northeast Asia as defined in this study includes the Russian Far East, Northeast China, the northern part of the Korean Peninsula, and Hokkaido Island (Japan). We determined the species richness of Northeast Asia at various spatial scales, analyzed the floristic relationships among geographic regions within Northeast Asia, and compared the flora of Northeast Asia with surrounding floras. The flora of Northeast Asia consists of 971 genera and 4953 species of native vascular plants. Based on their worldwide distributions, the 971 gen- era were grouped into fourteen phytogeographic elements. Over 900 species of vascular plants are endemic to Northeast Asia. Northeast Asia shares 39% of its species with eastern Siberia-Mongolia, 24% with Europe, 16.2% with western North America, and 12.4% with eastern North America. -

BWSR Featured Plant Name: Purple-Stemmed Angelica

BOARD OF WATER rn, AND SOIL RESOURCES 2018 December Plant of the Month BWSR Featured Plant Name: Purple-stemmed Angelica (Angelica atropurpurea) Plant family: Carrot (Apiaceae) Purple-stemmed A striking 6 to 9 feet tall, purple- Angelica grows in stemmed Angelica is one of moist conditions in full sun to part Minnesota’s tallest wildflowers. This shade, reaching as robust herbaceous perennial grows tall as 9 feet. along streambanks, shores, marshes, Photo Credit: calcareous fens, springs and sedge Karin Jokela, Xerces Society meadows — often in calcium-rich alkaline soils. The species epithet “atropurpurea” comes from the Latin words āter (“dark”) Plant Stats and purpūreus (“purple”), in reference to the deep purple color of the stem. WETLANDSTATEWIDE Flowers bloom from May to July. Like INDICATOR other plants in the carrot family, the STATUS: OBL flowers provide easy-to-access floral PLANTING resources for a wide diversity of flies, METHODS: bees and other pollinators. Although Bare-root, not confirmed for this species, the containers, nectar of other members of the Angelica seed genus can have an intoxicating effect on insects. Both butterflies and bumble bees are reported to lose flight ability, or fly clumsily, for a short period after consuming the nectar. Purple-stemmed Angelica is a host plant for the Eastern black swallowtail butterflyPapilio ( polyxenes asterius) and the umbellifera borer moth (Papaipema birdi). Uses Native American cultures. The consumption must be done projects. Restorationists plant also has many culinary with EXTREME CAUTION. appreciate its ability to Purple-stemmed Angelica uses: the flavorful stems are The similar water hemlock tolerate wet soils, part shade has a long history of human similar in texture to celery and poison hemlock are both and high weed pressure use. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), Including Artemisia and Its Allied and Segregate Genera Linda E

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 9-26-2002 Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E. Watson Miami University, [email protected] Paul E. Bates University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Timonthy M. Evans Hope College, [email protected] Matthew M. Unwin Miami University, [email protected] James R. Estes University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub Watson, Linda E.; Bates, Paul E.; Evans, Timonthy M.; Unwin, Matthew M.; and Estes, James R., "Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera" (2002). Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences. 378. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub/378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research2 BMC2002, Evolutionary article Biology x Open Access Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E Watson*1, Paul L Bates2, Timothy M Evans3, -

Part 2 – Fruticose Species

Appendix 5.2-1 Vegetation Technical Appendix APPENDIX 5.2‐1 Vegetation Technical Appendix Contents Section Page Ecological Land Classification ............................................................................................................ A5.2‐1‐1 Geodatabase Development .............................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐1 Vegetation Community Mapping ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐1 Quality Assurance and Quality Control ............................................................................ A5.2‐1‐3 Limitations of Ecological Land Classification .................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Field Data Collection ......................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐3 Supplementary Results ..................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐4 Rare Vegetation Species and Rare Ecological Communities ........................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Supplementary Desktop Results ..................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐10 Field Methods ................................................................................................................. A5.2‐1‐16 Supplementary Results ................................................................................................... A5.2‐1‐17 Weed Species -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E.