In Search of Japanoise Globalizing Underground Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pender Humane Society and Their Phone 910-937-1164 Or 910-455-0182

Expanding Families One Pet at a Time July 2017 Priceless TM Celebrating the Bond Between Humans and Animals PawPrints Magazine's Homeless cover Model Summertime is here and that can only mean one thing… it’s Kitten Season! Across the nation, millions of kittens are being born and are waiting for loving homes. My name is Elmer and Photo by: Michael Cline Photography I’m one such kitten. I was once sitting at Brunswick County Animal Control, but Adopt-An-ANGEL found me and took me in. Did you know they have over ONE HUNDRED kittens in their foster care program right now? Kittens just as precious as me, in all colors, sizes and shapes. I’m just 10-weeks-old and simply adorable. I love to play with toys, but I will also curl up happily on your chest and fall fast asleep. If you’d like to give me a loving home, please call my Adopt-An-ANGEL foster mom at 910-471-6909. She can also tell you about the other kittens up for adoption. And don’t forget, your county’s Animal Control is full of kittens too, so please visit and please look through this magazine at all the kittens pictured. There is someone for everyone! I’d now like to thank Michael Cline Photography for capturing my kittenish charm in my fruit-tastic cover photo and in the patriotic photo above. Being a cover model is quite exciting, but I’d much rather be someone’s beloved family member. “IF YOUR DOG IS NOT COMING TO YOU… YOU SHOULD BE COMING TO US!” Classes begin July 31st $10.00 off with this ad (first time students only) Not for profit service organization since 1971 910-392-2040 Visit our website at www.adtc.us Looking for the Hi, my name is Alice perfect house (35608354) and I’m a companion? One Patchwork Siamese who is small and girl. -

Noise Music As Performance OPEN BOOK 004 the Meaning of Indeterminacy: Noise Music As Performance Joseph Klett and Alison Gerber

The Meaning of Indeterminacy: Noise Music as Performance OPEN BOOK 004 The Meaning of Indeterminacy: Noise Music as Performance Joseph Klett and Alison Gerber Pamphlets for print and screen. Share, distribute, copy, enjoy. Authors’ words and IP are their own. In aesthetic terms, the category of ‘sound’ is often split in two: ‘noise’, which is chaotic, unfamiliar, and offensive; and ‘music’, which is harmonious, resonant, and divine. These opposing concepts are brought together in the phenomenon of Noise Music, but how do practitioners make sense of this apparent discordance? Analyses that treat recorded media as primary texts declare Noise Music to be a failure, as a genre without progress. These paint Noise as a polluted form in an antagonistic relationship with traditional music. But while critiques often point to indeterminate structure as indicative of the aesthetic project’s limitations, we claim that indeterminacy itself becomes central to meaningful expression when the social context of Noise is considered. Through observational and interview data, we consider the contexts, audiences, and producers of contemporary American Noise Music. Synthesizing the performance theories of Hennion and Alexander, we demonstrate how indeterminacy situated in structured interaction allows for meaning-making and sustains a musical form based in claims to inclusion, access, and creative freedom. We show how interaction, not discourse, characterizes the central performance that constructs the meaning of Noise. Noise Music is characterized by abrasive frequencies and profuse volume. Few would disagree that the genre can be harsh, discordant, unlistenable. In aesthetic terms, “noise” is sound which is chaotic, unfamiliar, and offensive, yet such sounds – discarded or avoided in traditional genres – becomes the very content of a musical form with the phenomenon of Noise Music (commonly shortened to the proper noun ‘Noise’). -

Adam Kurland and Lucas Jansen

Personal Statement dam Kurland is the director of Knowing that the history of America is embroiled in Fantasy Sports (née Rotisserie) A the upcoming documentary muck, it wasn’t so much a choice to make this film as it was our American duty to “This is Not a Robbery,” the honor this world-changing almost-sport. Whether Fantasy got its start in the front Silly Little Game story of the world’s Oldest Bank Robber, a credit he shares alongside partner office of the 1963 Raiders, the mind of a Harvard sociologist, ancient Polynesian Lucas Jansen. Mr. Kurland’s music-video customs, or (and this one is probably the truest) with eleven self-described “stat- work has been featured on the MTV and crazed schmucks” in a mediocre French restaurant on New York’s upper East Side; Fuse networks. A native of Los Angeles few to none of the millions of fantasy players who make up today’s multi-billion-dollar and graduate of the USC Cinema- fantasy industry know anything about its origins, nor do they pay any respect or divi- Television program, Mr. Kurland currently lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. dends to its founders. Now they will. For us, fantasy is about people who take epically exciting, endlessly complicated, Directed by Adam Kurland and Lucas Jansen Directed ucas Jansen and directing furiously competitive alternative universes just as seriously (if not more seriously) as partner (and friend since they take their own everyday lives. It’s a passion that makes sense after childhoods L Mr. Kramer’s 7th-grade history class) Adam Kurland founded Red Marker spent, in our cases, pretending to be Magic, passing to ourselves as Kareem, dunk- Films in 2005, with the goal of producing ing on Nerf hoops, cheering like 30,000 fans and calling our own play by play. -

Extreme Rock from Japan

Extreme Rock From Japan Joe Paradiso MIT Media Lab Japan • Populaon = 127 million people (10’th largest) – Greater Tokyo = 30 million people (largest metro in world) – 3’rd largest GDP, 4’th largest exporter/importer • Educated, complex, and hyper mo<vated populace – OCD Paradise… • Many musicians, and the level of musicianship is high! • Japan readily absorbs western influences, but reinterprets them in its own special way… – Creavity bubbles up in crazy ways from restric<ve uniformity – Get Western idioms “wonderfully” wrong! – And does it with gusto! Nipponese Prog • Prog Rock is huge in Japan (comparavely speaking….) – And so is psych, electronica, thrash bands, Japanoise (industrial), metal, etc. • I will concentrate on Early Synth music - Symphonic Prog – Fusion/jazz - RIO (quirky) prog – Psychedelic/Space Rock – by Nature Incomplete • Ian will cover Hip Hop, Miku, etc. Early (70s) Electronics – Isao Tomta 70’s Rock Electronics - YMO • Featuring Ryuichi Sakamoto 70s Berlin-School/Floydish Rock Far East Family band • Parallel World produced by Klaus Schulze – Entering – 6:00, Saying to the Land (4:00) 70’s Progish Jazz – Stomu Yamash'ta • Supergroup “Go” • Freedom is Frightening, 5:00, Go side B Other Early 70’s Psych (Flower Travelin’ band) • Satori, pt. II, middle Early Symphonic Prog - Shingetsu 1979 • Led by Makoto Kitayama (Japanese Peter Gabriel) • Oni Early Symphonic Prog – Outer Limits (1985) 1987 2007 • The Scene Of Pale blue (Part One) – middle • Plas<c Syndrome, Consensus More Early Symphonic Prog – Mr. Sirius 1987 1990 -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

16 August 1984 Greenbelt News Review

Council Reviews Coming Year's 6rttnbtlt ca,ital Improvements Projects by Leta Mach How to spend $291,000 was the pleasant subject city council considered at a July 31 work session. The money has been designated for fiscal year 1984-85 capital improve ment projects. ltws Rt1Jitw Some projects had already been approved in FY 1983- AN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER 84. Totaling $49,500, the projects are Attick Park entrance road reconstruction, work on stairs and sidewalk to the post Volume 47 Numbez: 39 P.O. Box 68, Greenbelt, Maryland 20770 Thurs., Aug. 16, 1984 office, Greenhill drainage work and Centerway resurfacing 1 with new curb and sidewalk. A large portion of the money get but instead listed as future would be used for street resur needs. The projects included facing on Julian Court, Lastner Northway resurfacing from Ri<tge 61-11 Considers Plans for Reconstruction Lane, Rosewood Drive, Periwin to the Northway fields (estimate kle Drive, Hamilton Place, Lake $19,000), lake dredging (estimate crest Drive (Lakecrest Circle so $85,000), Eastway reconstruction .Of Plateau PL and Ridge Road Sidewalk Lakeside), Lakeside Drive (West (estimate $30,000), Hillside re way to Lakecrest), Westway construction Northway to Cres by Mavis Fletcher The discussion about the Ridge Cooperative League of the USA. (Ridge to resurfaced section), cent (estimate $55,000), resur Greenbelt City Manager Ro:id reconstruction centered vri CLUSA is currently working on Springhill Lane ( Breezewood to facing of half of the North Cen marily on whether a sidewalk drafting tax legislation which resurfaced section) and the At ter parking lot (estimate ~l'l,- James K. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/Notes Format Quantity

Label ARTIST Piece Tracks/notes Format Quantity Sire Against Me! 2 song 7" single I Was A Teenage Anarchist (acoustic) 7" vinyl 2500 Sub-pop Album Leaf There Is a Wind Featuring 2 new tracks, 2 alternate takes 12" vinyl 1000 on songs from "A Chorus of Storytellers" LP Righteous Babe Ani DiFranco live @ Bull Moose recorded live on Record Store Day at CD Bull Moose in Maine Rough Trade Arthur Russell Calling Out of Context 12 new tracks Double 12" set 2000 Rocket Science Asteroids Galaxy Tour Fun Ltd edition vinyl of album with bonus 12" 250 track "Attack of the Ghost Riders" Hopeless Avenged Sevenfold Unholy Confessions picture disc includes tracks (Eternal 12" vinyl 2000 Rest, Eternal Rest (live), Unholy Confessions Artist First/Shangri- Band of Skulls Live at Fingerprints Live EP recorded at record store CD 2000 la 12/15/2009 Fingerprints Sub-pop Beach House Zebra 2 new tracks and 2 alternate from album 12" vinyl 1500 "Teen Dream" Beastie Boys white label 12" super surprise 12" vinyl 1000 Nonesuch Black Keys Tighten Up/Howlin' For 12" vinyl contains two new songs 45 RPM 12" Single 50000 You Vinyl Eagle Rock Black Label Society Skullage Double LP look at the history of Zakk Double LP 180 Wylde and Black Label Society Gram GREEN vinyl Graveface Black Moth Super Eating Us extremely limited foil pressed double LP double LP Rainbow Jagjaguwar Bon Iver/Peter Gabriel "Come Talk To Bon Iver and Peter Gabriel cover each 7" vinyl 2000 Me"/"Flume" other. Bon Iver track is EXCLUSIVE to this release Ninja Tune Bonobo featuring "Eyes -

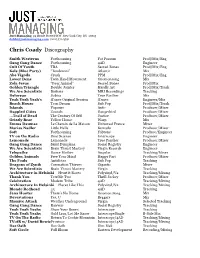

Chris Coady Discography

Just Managing 99 Reade Street PHW New York City, NY 10013 [email protected] (212) 571-3591 Chris Coady Discography Smith Westerns Forthcoming Fat Possum Prod/Mix/Eng Gang Gang Dance Forthcoming 4AD Engineer Cult Of Youth TBA Sacred Bones Prod/Mix/Eng Kele (Bloc Party) “Tenderoni” Atlantic Mix Abe Vigoda Crush PPM Prod/Mix/Eng Lower Dens Twin Hand Movement Gnomonsong Mix Zola Jesus “Poor Animal” Sacred Bones Prod/Mix Golden Triangle Double Jointer Hardly Art Prod/Mix/Track We Are Scientists Barbara MRI Recordings Tracking Delorean Subiza True Panther Mix Yeah Yeah Yeah’s iTunes Original Session iTunes Engineer/Mix Beach House Teen Dream Sub Pop Prod/Mix/Track Islands Vapours Anti- Producer/Mixer Dappled Cities Zounds Dangerbird Producer/Mixer ...Trail of Dead The Century Of Self Justice Producer/Mixer Grizzly Bear Yellow House Warp Mix Emma Daumas Le Chemin de La Maison Universal France Mixer Marisa Nadler Little Hells Kemado Producer/Mixer Soft Forthcoming Fabtone Produce/Engineer TV on the Radio Dear Science Interscope Engineer Lemonade Lemonade True Panther Producer/Mixer Gang Gang Dance Saint Dymphna Social Registry Engineer We Are Scientists Brain Thrust Mastery Virgin Records Engineer Telepathe Dance Mother Angular Tracking/Mixer Golden Animals Free Your Mind Happy Part Producer/Mixer The Foals Antidotes Sub Pop Tracking Dragons of Zynth Coronation Thieves Gigantic Mixer We Are Scientists Brain Thrust Mastery Virgin Tracking Architecture in Helsinki Heart it Races Polyvinyl/V2 Tracking/Mixing Thank You Terrible Two Thrill Jockey -

1989 and After

1 1989 AND AFTER BEGINNINGS It begins with a string quartet: two violins, a viola, and a cello pumping notes up and down like pistons. An image of the American machine age, hallucinated through the sound of the European Enlightenment. Th e image is strengthened as a voice—mature, female, American—intones an itinerary: “From Chicago . to New York.” Th e sound is prerecorded, digitally sampled and amplifi ed through speakers beside the ensemble. More samples are added: more voices; the whistles and bells of trains; one, two, three, or even more string quartets. Rapidly the musi- cal space far exceeds what we see on stage. Th is is a string quartet for the media age, as much recordings and amplifi cation as it is the four musicians in front of us. Yet everything extends from it and back into it, whether the quartet of quartets, which mirror and echo each other; the voices, which seem to blend seamlessly with the instrumental rhythms and melodies; or the whistles, which mesh so clearly with the harmonic changes that it seems certain they come from an unseen wind instrument and not a concrete recording. ••• It begins with thumping and hammering, small clusters struck on the piano key- board with the side of the palm or with three fi ngers pressed together, jabbing like a beak. Th e sound recalls a malevolent dinosaur or perhaps a furious child, but it isn’t random; a melody of sorts, or an identifi able series of pitches at least, hangs over the tumult. Aft er twenty seconds or so the thunder halts abruptly for a two- note rising motif played by the right hand, which is then imitated (slightly altered) 1 2 1989 AND AFTER by the left . -

Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, the Haters, Hanatarash, the Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese…

As Loud as Possible As Loud as Possible Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Concert de Hanatarash, Toritsu Kasei Loft, Tokyo, 1985 (Photos : Gin Satoh) Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… Un parcours parmi les grandes figures du harsh noise, au sein de l’internationale du bruit sale de ses origines à nos jours. AS LOUD AS 48 POSSi- 49 bLe. Whitehouse, Merzbow, Maurizio Bianchi, The Haters, Hanatarash, The Gerogerigege, Massona, Prurient, John Wiese… A tour among the major figures in harsh noise, within dirty Noise International—from its inception to the present day. Fenêtre ouverte. Le bruit, c’est ce son fronde, indompta- juste une main pour sculpter, une intention pour guider, Mais comment la musique a-t-elle osé muter en ça ? ble, discordant, une puanteur dans l’oreille, comme l’a écrit à peine une idée pour le conceptualiser. Il n’est pas une Objectivement, si on regarde la tête du harsh noise, son Ambrose Bierce dans son Devil’s Dictionary, ce que tout musique bruyante mais une musique-bruit taillée, pas un nom, il faut tout de même se pencher un peu en arrière, le oppose et tout interdit à la musique. Le bruit sévère, le bruit genre, encore moins un mélange, car s’il est né d’amonts XXe siècle brouhaha, pour comprendre cette « birth-death dur, le harsh noise, c’est, pire encore, le chaos volontaire, la lisibles dans l’histoire de la musique, dans l’histoire du XXe experience », si l’on m’autorise à citer le titre d’un disque de crasse en liberté, même pas la musique de son-bruits rêvée siècle, il n’a dans sa pratique et sa nature d’autre horizon Whitehouse, le premier de surcroît. -

Epiphanies L(Lll-T!{6 F,',!"L : ARTSTSI Ffiiii,Ffi

Epiphanies l(lLL-T!{6 F,',!"l : ARTSTSI ffiiii,ffi E HATEUHIT Yamatsuka Eye's artwork for the Eat Srrit ,Vorbe ,ttusrc cassette (cilca 1988) It was exactlythe sort of thingthat 15 year olds aren't musicianship,fidelity, funkiness, lyrical content, closerto the middle.They weren't well known,but at grew supposedto hear: Eat Shit NoiseMusic. Late night rhythmicprowess, historical relevance, etc had no least those cats had decentdistribution! | collegeradio had introducedme to Japan'svirtuoso businesshere. This was stuff so uglyonly a motheror curious.What other soundslived in the undergrowth, bassand drumsduo, Ruins, and my questfor material close relativecould love it, and thus I quicklyfound off the map,in placesyou needan obscurecatalogue by the groupwas sendingme down increasingly myselfin the family. to locate? unusualpaths. Eat Shlt was my best lead- a bootleg Forthis was the first musicthat I could reallycall my With its no-fiXerox artwork and poorlytyped tracklist, cassetteof Japanesegroups compiled by RRRecords, own. Reachingliterally across the globe,the most Eat Shlt was a refreshingreminder that you didn't and availablevia theirmail order catalogue. Ruins unmarketablesounds had locatedthe rightears and need moneyto make musicor get it heard."All song wereon the tracklistand the pricewas cheap. transmutedinto personaltreasure. Nobody was telling [sic] swipedfrom existingphonograph records, used The cassettearrived suspiciously fast, just two days me howto listen or what to listenfor. I had discovered withoutpermission," the liner notes boasted.Of after I'd postedmy cheque.I tore openthe package, it unaidedby recommendation,radio play or a course,nobody minded this bootlegger.RRRecords armedmy tape deck, and crankedthe volume.What I journalist'sreview.