The Burgeoning Recognition and Accommodation of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commission on Narcotic Drugs Report of the Sixteenth Session (24 April - 10 May 1961)

E/35U / E/CN.7/411 · __n~~VANCE UN UBRARY NOV 1 ;j )~bl UN/SA COLLECl\ON UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ON NARCOTIC DRUGS REPORT OF THE SIXTEENTH SESSION (24 APRIL - 10 MAY 1961) ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL OFFICIAL RECORDS: THffiTY-SECOND SESSION J SUPPLEMENT No. 9 GENEVA CONTENTS Chapter Paragraphs Page I. Organizational and administrative matters. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1-20 Representation at the session. 1-11 Opening and duration of the session . .. .. .. .. .. ... ........ ... 12 2 Election of officers ... ............. ..... ... ..... .. .......... ... 13 2 Adoption of the agenda ....... ......... ....... ... .......... ... ..... 14-15 2 Report of the Commission to the Economic and Social Council on its sixteenth session. .... ...... .. ... ......... ....... ... .... .. ........... .. .. 16 3 Organization of the seventeenth session of the Commission ............. ... .. 17-19 3 Place of meeting of the seventeenth session of the Commission..... .......... 20 3 II. Implementation of the treaties and international control ....... ................. 21-70 4 Report of the Division of Narcotic Drugs ...... .. .. ...... .......... .. ... 21-23 4 List of drugs under international control. ...... .. ... .. ............ ....... 24-27 4 Ratifications, acceptance, accessions and declarations concerning the multilateral treaties on narcotic drugs . .... .. .................. .. ........... .... 28-31 4 Annual reports of governments made in pursuance of article 21 of the 1931 Convention . .. .. .. .... .. .. .. ...... .. .... .... .. .... ...... -

Inside Cover

Acknowledgements The Improving ATS Data and Information Systems project is managed by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Regional Centre for East Asia and the Pacific. It is the primary mechanism in the region for monitoring drug abuse patterns and trends and for disseminating the most up-to-date information on those patterns and trends. Grateful appreciation is expressed to the national drug control agencies participating in the Drug Abuse Information Network for Asia and the Pacific (DAINAP) in Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam and to the staff of each agency and affiliated office for compiling and submitting the data requested and for reviewing and clarifying their data submissions prior to publication of the report. Without the significant effort of the 13 national coordinators and drug control agencies participating in the DAINAP surveillance project, this report could not have been compiled. Particular acknowledgement is given to the Governments of Australia and Japan for providing funding to support the development and maintenance of this activity. The core team that prepared this report was comprised of Nicholas J. Kozel, Expert Consultant, Johannes Lund, Data Integrity Consultant, Jeremy Douglas, UNODC Regional Project Coordinator for Improving ATS Data and Information Systems (TDRASF97) and Rebecca McKetin, Senior Research Fellow National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre. For more information about the Improving -

MEDICAL MARIJUANA in the WORKPLACE Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Bockius & Lewis Morgan, © 2018

4/30/2018 MEDICAL MARIJUANA IN THE WORKPLACE Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Bockius & Lewis Morgan, © 2018 I. Agenda A. Overview: Medical Cannabis B. Medical Cannabis Use Is Now Gaining Broad Acceptance and Support Within the Medical Community C. Pennsylvania’s Medical Marijuana Act: Background D. State Versus Federal Law E. Pennsylvania’s Medical Marijuana Act: Specific Questions for Employers F. General Guidance for Employers with Operations in Multiple States 2 II. Overview: Medical Cannabis A. History of cannabis use: • Documented use in China as early as 2700 BCE • India, Africa & the Roman Empire for >2000 years • 1200 BCE: Egyptians use Cannabis as anti-inflammatory, for glaucoma treatment • 1000 BCE: India uses cannabis for Anesthetic • 600 BCE: Greece uses cannabis for anti-inflammatory, earache & edema • 1 CE: Chinese recommend cannabis for >100 conditions • 79 CE: Pliny the Elder writes about medical cannabis 3 1 4/30/2018 II. Overview: Medical Cannabis (cont.) 800 CE: Cannabis continues to be used medicinally; labeled by some as “lethal poison.” 1538 CE: Hemp used by English scientists 1621-1652 CE: English scholars recommends cannabis as treatment for depression, inflammation, & joint pain 1799 CE: Napoleon brings Marijuana to France from Egypt 1840: Cannabis used in UK by Queen Victoria for menstrual cramps; becomes regularly used in Western medicine 1611 CE: Jamestown settlers introduce cannabis to North America 1745 CE: George Washington grows hemp, diary states he is interested in cannabis as medicine 4 II. Overview: Medical Cannabis (cont.) • 1774 CE: Thomas Jefferson grows hemp • The United States included cannabis in its pharmacopeia from 1850-1941 • At one time, it was one of the most frequently prescribed medications by US physicians • By 1936: Cannabis is regulated in all 48 states. -

Africa Use of Both Air and Sea to Traffic Heroin

48 INCB REPORT 2016 A. Africa use of both air and sea to traffic heroin. According to UNODC, 11 per cent of global opiate users live in Africa, and more than half of them in West and Central Africa. 1. Major developments 362. West Africa, a subregion that has suffered from vio- 357. Africa is perceived mainly as a transit region for lent conflicts and political instability, has been increasingly drug trafficking, but it is increasingly becoming a con- affected by operations by well-organized criminal groups sumer and a destination market for all types of drugs of that involve not only drug trafficking from South America abuse. That trend could, in part, be attributed to regional to Europe but also local consumption and manufacture of drug trafficking that has caused a supply-driven increase synthetic drugs destined mainly for markets in Asia. The in the availability of different drugs. yearly value of cocaine transiting West Africa is estimated to be $1.25 billion. Besides the trafficking of cocaine, 358. Illicit production of, trafficking in and abuse of heroin trafficking is also occurring in the subregion. cannabis have remained major challenges throughout many parts of Africa, with an estimated annual preva- lence of cannabis use of 7.6 per cent, twice the global 2. Regional cooperation average of 3.8 per cent. Africa also remains a major pro- duction and consumption region for cannabis herb and 363. In November 2015, the West Africa Coast Initiative accounted for 14 per cent of cannabis herb seizures organized the third programme advisory committee worldwide. -

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

United States Department of State Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume II Money Laundering March 2019 INCSR 2019 Volume II Money Laundering Table of Contents Common Abbreviations ........................................................................... 6 Definitions ................................................................................................. 9 Legislative Basis and Methodology for the INCSR .............................. 14 Overview .................................................................................................. 16 Training Activities ................................................................................... 20 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (FRB) ................. 20 Department of Homeland Security ........................................................ 21 Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) ......................................................... 21 Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) ...................................... 21 Department of Justice ............................................................................ 22 Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) .............................................. 22 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) ................................................... 22 Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and Training (OPDAT) .................................................................................... 23 Department of State -

Drug Market Trends: Cannabis Opioids

DRUG MARKET TRENDS: CANNABIS 3 OPIOIDS © United Nations, June 2021. All rights reserved worldwide. ISBN: 9789211483611 WORLD DRUG REPORT 2021 REPORT DRUG WORLD eISBN: 9789210058032 United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21.XI.8 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. Suggested citation: World Drug Report 2021 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21.XI.8). No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC. DISCLAIMER The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement. Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Website: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr2021.html PREFACE 3 Drugs cost lives. unemployment and inequalities, as the world lost 114 million jobs in 2020. In doing, so it has created conditions that leave In an age when the speed of information can often outstrip more people susceptible to drug use and to engaging in illicit Preface the speed of verification, the COVID-19 pandemic has taught crop cultivation. -

Modernization of the Current Cannabis Legal Framework and Its Potential Economic Gains

ANNIJA SAMUŠA MODERNIZATION OF THE CURRENT CANNABIS LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ITS POTENTIAL ECONOMIC GAINS RGSL RESEARCH PAPER No. 19 Riga Graduate School of Law Established in 1998, the Riga Graduate School of Law (RGSL) has emerged as a leading legal education and research institute in the Baltic region. RGSL offers numerous study programmes in the area of International and European Law at bachelor and master’s level and cooperates with the University of Copenhagen on a joint doctoral programme. The School benefits from partnerships with numerous leading European universities and cooperates closely with the University of Latvia, the major shareholder. In addition to its growing resident faculty, RGSL also benefits from the involvement of a large number of eminent scholars and practitioners based in the local environment, elsewhere in Europe, and overseas. The School is located in the Art Nouveau district of Riga and hosts an outstanding law library. A primary objective of RGSL is to contribute to the development of Latvia and the wider region by educating new generations of motivated and highly skilled young scholars and professionals capable of contributing to the ongoing process of European integration. Research and education in the area of international and European law are integral to the realisation of this objective. The present series of Research Papers documents the broad range of innovative scholarly work undertaken by RGSL academic staff, students, guest lecturers and visiting scholars. Scholarly papers published in the series have been peer reviewed. Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief: George Ulrich (Ph.D) Editorial Board: Mel Kenny (Dr.iur.) Martins Mits (Dr.iur.) Ilze Ruse (Dr.phil.) Ineta Ziemele (Ph.D) Gaļina Zukova (Ph.D) Assistant to the Editorial Board: Ligita Gjortlere (M.Sci.Soc.) ISSN 1691-9254 © Annija Samuša, 2017 About the author: Annija Samuša graduated from the University of Bremen Faculty of Economics in 2014 and later on obtained her LL.M in Law and Finance from the Riga Graduate School of Law in 2016. -

DRUG MARKET TRENDS: CANNABIS OPIOIDS © United Nations, June 2021

DRUG MARKET TRENDS: CANNABIS OPIOIDS © United Nations, June 2021. All rights reserved worldwide. ISBN: 9789211483611 WORLD DRUG REPORT 2021 REPORT DRUG WORLD eISBN: 9789210058032 United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21.XI.8 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. Suggested citation: World Drug Report 2021 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21.XI.8). No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from UNODC. Applications for such permission, with a statement of purpose and intent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Research and Trend Analysis Branch of UNODC. DISCLAIMER The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNODC or contributory organizations, nor does it imply any endorsement. Comments on the report are welcome and can be sent to: Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime PO Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria Tel: (+43) 1 26060 0 Fax: (+43) 1 26060 5827 E-mail: [email protected] 2 Website: www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/wdr2021.html PREFACE 3 Drugs cost lives. unemployment and inequalities, as the world lost 114 million jobs in 2020. In doing, so it has created conditions that leave In an age when the speed of information can often outstrip more people susceptible to drug use and to engaging in illicit Preface the speed of verification, the COVID-19 pandemic has taught crop cultivation. -

Cannabis Regulation and Cannabis Derived Products

Cannabis Regulation and Cannabis Derived Products Austria FPLP 6 Brazil Felsberg Advogados 21 Colombia MTA 23 Germany Rittershaus 35 Gibraltar Hassans International Law Firm 46 Hong Kong Charltons 50 India Dua Associates 57 Israel AYR 81 Malta DF Advocates 86 Netherlands Ekelmans & Meijer Advocaten 91 Portugal Sérvulo & Associados 94 South Korea Barun Law 102 Spain Lopez Ibor Abogados 105 Turkey Gün & Partners 108 UK Mishcon de Reya 112 Ukraine Asters 117 Uruguay Hughes & Hughes 120 USA Bell Nunnally 123 USA Carter Ledyard & Milburn 144 AUSTRIA Polak & Partners Rechtsanwälte Gmb 1. What regulatory frameworks are relevant to medical and recreational cannabis and the cultivation, manufacture, distribution etc of cannabis and cannabinoids in Austria? 1.1. Narcotics framework In Austria, cannabis is subject to the provisions of the Austrian Narcotic Substances Act (Bundesgesetz über Suchtgifte, psychotrope Sto!e und Drogenausgangssto!e; Suchtmittelgesetz (SMG)). The classification of cannabis as a narcotic substance is based on the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. As required by Article 36 of the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, o!ering, o!ering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokerage, dispatch, dispatch in transit, transport, importation and exportation of drugs contrary to the provisions of this Convention shall constitute punishable o!ences. This Article was implemented via Section 27 et seqq in Austria as follows: a) § 27 (1) SMG – Illegal handling of narcotics (basic criminal o!ence): It is a punishable o!ence to acquire, possess, produce, transport, import or export, or to o!er to, give to or procure for a third person, cannabis containing more than 0.3% tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). -

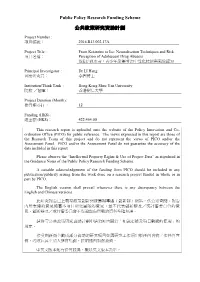

Research Report Is Uploaded Onto the Website of the Policy Innovation and Co- Ordination Office (PICO) for Public Reference

Public Policy Research Funding Scheme 公共政策研究資助計劃 Project Number : 項目編號: 2016.B13.002.17A Project Title : From Ketamine to Ice: Neutralisation Techniques and Risk 項目名稱: Perception of Adolescent Drug Abusers 從K仔到冰毒:青少年濫藥者的中性化技術與風險認知 Principal Investigator : Dr LI Hang 首席研究員: 李鏗博士 Institution/Think Tank : Hong Kong Shue Yan University 院校 /智庫: 香港樹仁大學 Project Duration (Month): 推行期 (月) : 12 Funding (HK$) : 總金額 (HK$): 422,464.00 This research report is uploaded onto the website of the Policy Innovation and Co- ordination Office (PICO) for public reference. The views expressed in this report are those of the Research Team of this project and do not represent the views of PICO and/or the Assessment Panel. PICO and/or the Assessment Panel do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report. Please observe the “Intellectual Property Rights & Use of Project Data” as stipulated in the Guidance Notes of the Public Policy Research Funding Scheme. A suitable acknowledgement of the funding from PICO should be included in any publication/publicity arising from the work done on a research project funded in whole or in part by PICO. The English version shall prevail whenever there is any discrepancy between the English and Chinese versions. 此研究報告已上載至政策創新與統籌辦事處(創新辦)網站,供公眾查閱。報告 內所表達的意見純屬本項目研究團隊的意見,並不代表創新辦及/或評審委員會的意 見。創新辦及/或評審委員會不保證報告所載的資料準確無誤。 請遵守公共政策研究資助計劃申請須知內關於「知識產權及項目數據的使用」的 規定。 接受創新辦全數或部分資助的研究項目如因研究工作須出版任何刊物/作任何宣 傳,均須在其中加入適當鳴謝,註明獲創新辦資助。 中英文版本如有任何歧異,概以英文版本為準。 From Ketamine to Ice: Neutralisation Techniques and Risk Perception of Adolescent -

F. Cannabis:Overview Arcotics, “Afghani

F. Cannabis: overview 39 Fig. 39. Cocaine consumption and purity- Fig. 40. Cocaine prevalence and purity- adjusted price in Western and Central adjusted price, United States, Europe, weighted by population of 2003-2012 countries, 2003-2012 200 3 300 2 180 2.5 160 250 140 2 200 120 100 1.5 150 1.5 80 1 100 60 40 0.5 50 20 Prevalence (percentage) Prevalence (percentage) Prevalence 0 1 0 0 Price per pure gram (United States dollars) Price per pure gram (United States dollars) States (United gram pure per Price 2003-2005 2004-2006 2005-2007 2006-2008 2007-2009 2008-2010 2009-2011 2010-2012 2003-2005 2004-2006 2005-2007 2006-2008 2007-2009 2008-2010 2009-2011 2010-2012 Prevalence of cocaine use in the past-year (age 15-64) Prevalence of cocaine use in the past-year (age 15-64) Purity-adjusted retail price (2012 dollars) Purity-adjusted retail price (2012 dollars) Source: UNODC annual report questionnaire, and Substance Source: UNODC annual report questionnaire. Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and price data Note: Prevalence figures displayed as moving average. from the System to Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence (STRIDE) database of the United States Drug Enforcement Agency. Note: Prevalence figures displayed as moving average tions, possibly including Asia; it is also likely that there is a link with South Africa.148 Lebanon appear to be destination countries for cocaine, The estimated prevalence of cocaine use in South Africa with Jordan and the Syrian Arab Republic serving as transit rose from 0.78 per cent of the general population in the countries.150 Annual seizures in China and India were 15-64 age bracket in 2008 to 1.02 per cent in 2011, con- below 100 kg in 2011; more significant, relative to the size firming the continued existence of a sizeable and appar- of the population, were the quantities (each in excess of ently expanding consumer market for cocaine. -

The Law of Prohibition

Country/Territory Possession Sale Transport Cultivation Notes [5] The law of prohibition exists but however with high availability of cannabis plants Albania Illegal Illegal Illegal Illegal throughout the country, this law is often unenforced.[6][7][8] Algeria Illegal Illegal Illegal Illegal Possession is illegal.[9] Legal for Legal for personal use in small amounts and for consumption in private locations. Public personal use consumption is generally accepted among young adults. Consumption for medical purposes is Argentina in small Illegal Illegal Illegal accepted but not legislated (only in private locations). Cultivating, selling and transporting large amounts (in amounts is illegal and punishable by present laws.[10] private) One or two plants may be privately grown for Main article: Cannabis in Australia personal use in the Decriminalized for personal use in small amounts in the Australian Capital Territory, South Australian Australia and the Northern Territory. It is a criminal offence in New South Wales, Queensland, Capital Western Australia, Victoria and Tasmania. In SA a person can legally grow 1 non-hydroponic Illegal Territory plant, and in the ACT 2 non-hydroponic plants may be grown on their own property for (decriminali Australia Illegal Illegal and South personal use, and in the N.T two non-hydroponic plants can be fined $200 with 28 days to pay zed in some [11] Australia. rather than face criminal charge. Enforcement varies from state to state, though a criminal states) Personal conviction for possession of a small amount is unlikely and diversion programs in these states [12] grows of up aim to divert offenders into education, assessment and treatment programs.