John Wendel, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRENT APPLIED PHYSICS "Physics, Chemistry and Materials Science"

CURRENT APPLIED PHYSICS "Physics, Chemistry and Materials Science" AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 1567-1739 DESCRIPTION . Current Applied Physics (Curr. Appl. Phys.) is a monthly published international interdisciplinary journal covering all applied science in physics, chemistry, and materials science, with their fundamental and engineering aspects. Topics covered in the journal are diverse and reflect the most current applied research, including: • Spintronics and superconductivity • Photonics, optoelectronics, and spectroscopy • Semiconductor device physics • Physics and applications of nanoscale materials • Plasma physics and technology • Advanced materials physics and engineering • Dielectrics, functional oxides, and multiferroics • Organic electronics and photonics • Energy-related materials and devices • Advanced optics and optical engineering • Biophysics and bioengineering, including soft matters and fluids • Emerging, interdisciplinary and others related to applied physics • Regular research papers, letters and review articles with contents meeting the scope of the journal will be considered for publication after peer review. The journal is owned by the Korean Physical Society (http://www.kps.or.kr ) AUDIENCE . Chemists, physicists, materials scientists and engineers with an interest in advanced materials for future applications. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 2.480 © Clarivate Analytics -

Organizing Committee Important Dates Topics Paper Submission

CALL FOR PAPERS “Smart Technology for an Intelligent Society” Organizing Committee General Co-Chairs Jinwook Burm Sogang University JinGyun Chung Jeonbuk Nat’l University Myung Hoon Sunwoo Ajou University Technical Program Co-Chairs Hanho Lee Inha University KyungKi Kim Daegu University Takao Onoye Osaka University Gabriel Lincon-Mora Georgia Tech. Special Session Co-Chairs Elena Blokhina University College Dublin Ittetsu Taniguchi Osaka University Lan-Da Van Nat’l Chiao Tung University Qiang Li UESTC Ross M. Walker University of Utah Minkyu Je KAIST Tutorial Co-Chairs Massimo Alioto Nat’l University of Singapore Andy Wu Nat’l Taiwan University Samuel Tang (Kea-Tiong Tang) Nat’l Tsing Hua University Hiroo Sekiya Chiba University Jongsun Park Korea University Timothy Constandinou Imperial College of London Important Dates Demo Session Co-Chairs Tobi Delbruck ETH Zurich Ji-Hoon Kim Ewha Womans University Plenary Session Co-Chairs Oct.5 Oct.23 Nov.16 Dec.7 Jan.8 Jan.11 Jan.29 Deog-Kyoon Jeong Seoul Nat’l University 2020 2020 2020 2020 2021 2021 2021 Boris Murmann Stanford University Robert Chen-Hao Chang Nat’l Chung Hsing University Junjin Kong Samsung Electronics Submission 1- Submission Submission Submission Notification of Notification of Final Publicity Co-Chairs deadline for deadline for deadline for deadline for Acceptance Acceptance Submission Hadi Heidari University of Glasgow Special Session Regular Papers CAS Trans. Papers Tutorials (for all papers) (for Demos Deadline Guoxing Wang Shanghai Jiao Tong University Proposals Proposals -

Andrea (Andy) Kim

ANDREA (ANDY) KIM Associate Professor of Organization and Human Resources SKK Business School, Sungkyunkwan (SKK) University Business Building #33515, 25-2 Sungkyunkwan-ro Jongno-gu Seoul, 03063, South Korea +82-2-740-1664 (work) · +82-2-760-0440 (fax) · [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sungkyunkwan (SKK) University, SKK Business School 03/2020-present Associate Professor of Organization and Human Resources 03/2014-02/2020 Assistant Professor of Organization and Human Resources Rutgers University, School of Management and Labor Relations 07/2011-present Research Fellow 01/2019 Visiting Professor, Department of Human Resource Management 05/2011-05/2014 Part-Time Instructor Baylor University, Hankamer School of Business 09/2017-10/2017 Visiting Professor, Department of Management University of Minnesota, Carlson School of Management 08/2013-02/2014 Visiting Scholar, Center for Human Resources and Labor Studies EDUCATION 10/2013 Ph.D., Industrial Relations and Human Resources, Rutgers University 10/2010 M.S., Industrial Relations and Human Resources, Rutgers University 02/2004 M.B.A., Seoul National University 02/2002 B.B.A., Korea Aerospace University GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS National Research Foundation of Korea 05/2017-04/2019 NRF-2017S1A5A8022504 (US$40,000) 05/2016-04/2017 NRF-2016S1A5A8019014 (US$10,000) 05/2015-04/2016 NRF-2015S1A5A8017362 (US$10,000) 05/2014-04/2015 NRF-2014S1A5A8019602 (US$10,000) SKK University 11/2017-10/2018 Sungkyun Research Fund (US$13,000) 11/2014-10/2015 Sungkyun Research Fund (US$13,000) Rutgers University 07/2012-06/2013 A Louis O. Kelso fellowship (US$12,500) by Employee Ownership Foundation 07/2011-06/2012 A Corey Rosen fellowship (US$5,000) by Rosen Ownership Opportunity Fund Others 12/2019 Research development fellowship (US$10,000) by SL Seobong Foundation 04/2015-04/2016 Research grants for Asian studies (US$15,000) by POSCO T. -

Author Information Author Information

Author Information Author Information Sang Hoon Bae, Sungkyunkwan University, Department of Education. Main research interests: edu- cation reform, policy evaluation, student engagement, college effects, effects of extended education participation. Address: Sungkyunkwan University. 507 Hoam Hall, 25–2, Sungkyunkwan-Ro, Jongno- Gu, Seoul, Korea. Zip. 03063. E-Mail: [email protected] Mark Bray, UNESCO Chair Professor of Comparative Education, Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong. Main research interests: comparative education methodology; shadow education (private supplementary tutoring). Address: Comparative Education Research Cen- tre, Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong. E-Mail: [email protected] Song Ie Han, Sungkyunkwan University, The Knowledge Center for Innovative Higher Education. Main research interests: education organization and reform, student engagement, college effects, edu- cational community. Address: Sungkyunkwan University. 212 600th Anniversary Hall , 25–2, Sungkyunkwan-Ro, Jongno- Gu, Seoul, Korea. Zip. 03063. E-Mail: [email protected] Denise Huang, Chief executive Officer, The HLH National Social Welfare Foundation. Main re- search interests: Afterschool program evaluations, quality indicators for effective afterschool pro- grams, social emotional learning, at-risk youths. Address: The HLH Foundation 1F., No.63, Zhongfeng N. Rd., Zhongli Dist., Taoyuan City 32086, Taiwan (R.O.C.) Sue Bin Jeon, Dongguk University. Main research interests: educational leadership, principalship, teacher education, school organization, diversity in education, student engagement. Address: 408 Ha- krimkwan, Dongguk University, Phildongro 1gil, Seoul, Korea. Zip: 04620. E-Mail: [email protected] Fuyuko Kanefuji, Bunkyo University, Department of Human Sciences. Main research interests: Program development and evaluation for extended education. Address: 3337 Minamiogishima, Ko- shigaya-shi, Saitama-ken, Japan. -

DAIN JUNG Curriculum Vitae, August 29, 2019

DAIN JUNG Curriculum Vitae, August 29, 2019 CONTACT INFORMATION College of Business, KAIST Office +82-(0)42-350-6351 Bldg. N22 #4108, 291 Daehakro, Yuseong-gu Mobile +82-(0)10-5755-9602 Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 34141 Email [email protected] EDUCATION 2020 Ph.D. in Business and Technology Management, College of Business, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon, Korea (expected) Dissertation title: Essays in Health Care Analytics Advisor: Hye-jin Kim and Minki Kim 2012 B.S. in Statistics, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Health Economics; Healthcare Analytics; Pharmaceutical Marketing RESEARCH Dissertation Research Essay #1: ‘‘An Empirical Investigation on the Economic Impact of Shared Patient Information among Doctors’’ (joint with Do Won Kwak, Hye-jin Kim and Minki Kim) Abstract: This study investigates how an increase in patient information sharing among doctors impacts healthcare costs. To this end, we explore this impact through two mechanisms—the informative role of patient health conditions and the cross-monitoring role against doctor-driven induced healthcare demands. We utilize a unique policy intervention (a drug utilization review) introduced in 2009 in Korea that enables doctors to share outpatients’ prescription histories. Using difference-in-differences, we found that, when patient information is improved, there is a reduction in pharmaceutical spending. This result is especially true for those patients who have relatively weak information-sharing capabilities. Using data on the amount of antibiotics prescribed for the common cold, we find that a cross-monitoring of prescriptions among doctors reduces the amount of unnecessary prescriptions and thus healthcare spending. -

College of Humanities Kyung Hee University

spring 2018 No. 10 CollegeCollege ofof HumanitiesHumanities KyungKyung HeeHee UniversityUniversity st 1 Semester, 2018 l Published by Jong-Bok Kim ll College of Humanities ll 02)961-0221~2 ll [email protected] SpringSpring 2018,2018, CollegeCollege ofof HumanitiesHumanities EventsEvents Ø Reorganization of the School of English The School of English has been reorganized into two departments: English Language and Literature (ELL) and Applied English Language and Translation Studies (AELTS). Through this reorganization, students will be offered greater balance and competitiveness in their various majors and prospective careers. Intellectual and pedagogical exchanges between ELL and AELTS will make a significant contribution to the overall quality of English language education at Kyung Hee University. ◉ Organizational Restructuring Before the restructuring After the restructuring English Language and Literature School of English Applied English Language & Translation Studies Ø 2018 Humanities Forum The Humanities Forum encourages in-depth scholarly research and the sharing of new academic projects with faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students. In the first semester of 2018, three faculty members, including new professor Sung-Beom Ahn from the Department of Korean Language and Literature, will discuss their research projects with the humanities community. The 2018 Humanities Forum will continue throughout the academic year with an engaging line-up of monthly presenters. ◉ Forum Schedule 2018.04.12 (Thurs) 18th Prof. Sung-Beom Ahn (Dept. of Korean) 2018.04.12 (Thurs) 19th Prof. Ji-Ho Chung (Dept. of History) 2018.06.14 (Thurs) 20th Prof. Woo-Sung Heo(Dept. of Philosophy) Ø Winter Overseas Training Program An Overseas Training Program was conducted during the 2017 winter vacation period in order to explore the relationship between global knowledge and the particularities of various majors. -

EASP Final Program Book Download

The 13th EASP annual conference: Social Policy and Gender in East Asia Program Book Program Overview Date Time Schedule Venue 08:30-9:00 Registration Posco Bd. B1 Lobby 09:00-10:30 Welcome Ceremony & Plenary Session Posco Bd. B153 10:40-12:10 Session Ⅰ-A, Ⅰ-B, Ⅰ-C, Ⅰ-D Posco Bd. 357-360 Lunch Break 12:10-13:20 Jinseonmi Bd. EASP Executive Committee Meeting Meeting Room Mi-gwan 1 Day 1 13:20-14:50 Session Ⅱ-A, Ⅱ-B, Ⅱ-C, Ⅱ-D, Ⅱ-E Posco Bd. 356-360 15:00-16:30 Session Ⅲ-A, Ⅲ-B, Ⅲ-C, Ⅲ-D, Ⅲ-E Posco Bd. 356-360 16:30-16:50 Tea Break 16:50-18:20 Session Ⅳ-A, Ⅳ-B, Ⅳ-C, Ⅳ-D Posco Bd. 357-360 Welcome Dinner International Education Bd. 18:35-20:00 with Special Korean Classical Music Performance LG Convention Hall 09:00-10:30 Session Ⅴ-A, Ⅴ-B, Ⅴ-C, Ⅴ-D Posco Bd. 357-360 10:30-10:50 Tea Break Day 2 10:50-11:50 Plenary Session Posco Bd. B153 11:50 Closing Ceremony & MOU Ceremony - 1 - 1. Welcome Ceremony & Plenary Session (Day 1) Day 1. 9:00-10:30 Venue Welcome Ceremony Moderator: Sophia Seung-yoon LEE (Chair of Department of Social Welfare, Ewha Womans University) Ÿ Welcoming Address Soondool CHUNG (Leader of BK21 PLUS Project “Social Work Leaders with Creative Capacities in the Changing Society”, Ewha Womans University) Ÿ Welcoming Address Posco Bd. B153 Choong Rai NHO (Director of Institute for Social Welfare Research, Ewha Womans University) Plenary Session Chair: Minah KANG (Ewha Womans University, Republic of Korea) Ÿ The Trilemma of the Care Economy: Possible Paths of Japan Mari MIURA (Sophia University, Japan) Ÿ The East Asian Miracle and the Wollstonecraft Dilemma: In Search for Joohee LEE (Ewha Womans University, a New Paradigm of Gender Egalitarian Social Rights Republic of Korea) 2. -

Heung Kyu Lee, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Heung Kyu Lee, Ph.D. BioMedical Research Center, #5106 [email protected] Homepage: https://www.heungkyulee.kaist.ac.kr/ Education Sep/2004-May/2009 Doctor of Philosophy in Immunobiology Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA Thesis title: Dendritic cells, Autophagy and Antiviral immunity Sep/1996-Aug/1998 Master of Science in Biotechnology Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea Mar/1992-Aug/1995 Bachelor of Engineering in Food Science and Technology Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea Positions and Employment Mar/2018- present Associate Professor (tenured) of Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon, Korea Sep/2016-Feb/2018 Associate Professor of Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea Apr/2017-present Adjunct Associate Professor of KAIST Institute for Health Science and Technology, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea Mar/2013-Feb/2015 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Dept. of Biological Sciences, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea Nov/2009-Aug/2016 Assistant Professor of Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering, KAIST, Daejeon, Korea Mar/2009-Jan/2010 Post-doctoral Associate of Immunobiology, HHMI, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT (PI: Ruslan Medzhitov, Ph.D.) Sep/2004-Feb/2009 Graduate Research Assistant of Immunobiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT (PI: Akiko Iwasaki, Ph.D.) Sep/2003-Aug/2004 Graduate Research Assistant of Immunology, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX (PI: Yong-Jun -

Dongguk University (Seoul, South Korea) Exchange Program

Office of International Education & Global Engagement 1108 Boylan Hall 2900 Bedford Avenue • Brooklyn, NY 11210 TEL: 718-951-5189 EMAIL: [email protected] http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/internationaleducation Brooklyn College – Dongguk University (Seoul, South Korea) Exchange Program The Brooklyn College exchange program with Dongguk University in Seoul, South Korea is open to Brooklyn College and other CUNY students. A wide range of academic coursework in English and intensive Korean language instruction are available. Participants will have the opportunity to study for a semester or year at this highly-rated private comprehensive university while paying CUNY tuition, international travel and onsite living costs. Financial aid and scholarships apply. This program is competitive and spaces are limited. A. Eligibility ● 3.0 minimum cumulative GPA. ● Completed 30 college credits by the semester prior to study abroad. ● Clear academic and disciplinary record. ● Acceptance as an exchange student by IEGE, Brooklyn College. B. IEGE Application Deadline for: • Fall or full year: No later than April 1st • Spring: No later than October 1st • More information on application process is below. C. Dongguk University Academic Offerings Students may apply to pursue coursework in many areas, including but not limited to: ● Advertising ● Economics ● Art ● Engineering ● Asian Languages & Literatures ● Film & Digital Media ● Biological & Environmental Sciences ● Mathematics ● Buddhist Studies ● Medical Biotechnology ● Business Administration ● Korean Studies ● Communications ● Political Science ● Computer Science ● Theater For more information on Dongguk University semester courses taught in English, see: http://www.dongguk.edu/mbs/en/subview.jsp?id=en_040700000000 1 Rvsd 08-08-2017 D. Academic Credit for Study Abroad Students receive credit and grades for the courses taken at Dongguk University. -

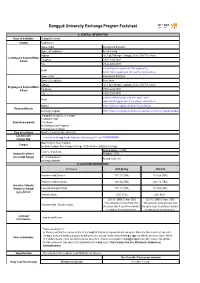

Dongguk University Exchange Program Factsheet

Dongguk University Exchange Program Factsheet A. GENERAL INFORMATION Name of Institution Dongguk University Country South Korea Name of Unit International Relations Name of Coordinator Soonbin Hong Address 30, 1 gil, Pildong-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul, 100-715, Korea Incoming and Summer/Winter (+82)2-2260-3463 School Telephone Fax (+82)2-2260-3878 [email protected] (for applicants) Email [email protected] (for partner universities) Name of Unit International Relations Name of Coordinator Sejin Kwon Address 30, 1 gil, Pildong-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul, 100-715, Korea Outgoing and Summer/Winter (+82)2-2260-3465 School Telephone Fax (+82)2-2260-3878 [email protected] (for applicants) Email [email protected] (for partner universities) Institute http://www.dongguk.edu/mbs/en/index.jsp Relevant Website Exchange program http://www.dongguk.edu/mbs/en/subview.jsp?id=en_040601020000 Dongguk University Seoul Campus Founded in 1906 General background 13 Colleges 66 Undergraduate Programs 136 Graduate Programs Type of Institution Private / Comprehensive University Location and http://www.dongguk.edu/mbs/en/subview.jsp?id=en_010600000000 Campus Map Main Campus: Seoul Campus Campus Bio-Medi Campus: Ilsan Campus (College of Life Science and Biotechnology) Undergraduate: 13,944 Total no. of students Student Enrollment Graduate: 3,595 (As of 2020 Spring) No. of international/ Around 1,549 / 35 exchange students B. ACADEMIC INFORMATION Information 2021-Spring 2021-Fall Residence Hall Check In 2021.02.(TBA) 2021.08.(TBA) Residence Hall Check Out 2021.06.(TBA) 2021.12.(TBA) Academic Calendar (Subject to change) Expected Orientation Date 2021.02.(TBA) 2021.08.(TBA) (yyyy-dd-mm) Semester starts 2021.03.02 2021.09.01. -

8Th Korean Screen Cultures Conference Conference Programme

2019 8th Korean Screen Cultures Conference Conference Programme UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE JUNE 5-7 2019 SPONSORED BY THE KOREA FOUNDATION KSCC 2019 Programme Schedule & Panel Plan Wednesday 5th June Time Event Location 16:50-17:05 Meet at Legacy Hotel lobby and walk to UCLan Legacy Hotel 17:05-17:30 Early-bird registration open Mitchell Kenyon Foyer 17:05-17:30 Wine and Pizza Opening Reception Mitchell Kenyon Foyer 17:30-19:30 Film Screening: Snowy Road (2015) Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 19:30-19:55 Director Q&A with Lee, Na Jeong Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 20:00-21:30 Participants invited join an unofficial conference dinner Kim Ji Korean Restaurant Thursday 6th June 08:45-09:00 Meet at Legacy Hotel lobby and walk to UCLan Legacy Hotel 09:00-09:15 Registration & Morning Coffee Foster LT Foyer 09:15-09:30 Opening Speeches FBLT4 09:30-11:00 Panel 1A: Horror Film and Drama FBLT4 09:30-11:00 Panel 1B: Transnational Interactions FBLT3 11:00-12:20 Coffee Break Foster LT Foyer 11:20-11:50 Education Breakout Session FBLT4 11:20-11:50 Research Breakout Session FBLT3 11:50 -13:20 Panel 2A: Industry and Distribution FBLT4 11:50 -13:20 Panel 2B: Diverse Screens FBLT3 13:20-14:20 Buffet Lunch Foster Open Space 14:25-15:55 Panel 3A: History/Memory/Reception FBLT4 14:25-15:55 Panel 3B: Korean Auteurs FBLT3 15:55-16:15 Coffee & Cake Break Foster LT Foyer 16:15-17:15 Keynote: Rediscovering Korean Cinema FBLT4 17:15-18:45 Film Screening: Tuition (1940) Mitchell Kenyon Cinema 18:45-19:15 Q&A with Chunghwa Chong, Korean Film Archive Mitchell Kenyon Cinema -

Curriculum Vita

Curriculum Vita PERSONAL PARTICULARS Name Kim Sun E-Mail Address [email protected] Mobile phone Number +82 10 2494 9069 Studio Address 63-6, Donggyo-ro, Mapo-gu, Seoul, Korea Date of Birth 1970. 11. 05 EDUCATION PhD Candidate Ewha Womans University 1999 MFA in Ceramic Design from Ewha Womans University Graduate School of Design 1994 BFA in Ceramic Arts from Ewha Womans University SOLO EXHIBITION 2018 REST, / GALLERY MIN, Seoul 2015 LOOKING INWARD2015 / Ewha art gallery, Seoul 2013 LOOKING INWARD / Korea Craft&Design Foundation gallery, Seoul 2009 ‘Rest Space’ / Korea Craft&Design Foundation gallery, Seoul 2005 A Home in Heyri made of Clay / Gallery TERRA, Gyeonggi-do Heyri 2003 SEA / .../ Gana Art Space, Seoul GROUP EXHIBITION 2018. 2018 Exhibition of Korea Woman Ceramicist Association / Gallery Min 2018. 因緣生起 / Gallery KWCA 2018. 9nd Seoul Modern Art Show 2018 / Hangaram Art Museum, Seoul Arts Center 2018. Exhibition of props for the New Year / Gallery KWCA 2017. 2017 Exhibition of Korea Woman Ceramicist Association / Gallery KWCA 2017. Be a picture everywher. Exhibition / Gallery Dalgam tree, Heyri 2016. Jewelry Fair /Seoul, COEX 2016. ECAF / Ewha art gallery 2015. 12. Home Table Deco Fair 2015 / Seoul, COEX 2016. 2016 Contemporary Ceramic Art in Asia / Taipei Branch, Taiwan 2016. TRANSITION/TRADITION / Gallerie Nvyã, New Delhi 2015. The fusion of tradition and modernity / Museum Mokpo 2015. 2015 Exhibition of Korea Woman Ceramicist Association / Gyeonggi Ceramic Museum 2015. China-Korea Invitational Ceramic Exhibition / Hanyang University Museum 2014. Australia-Korea Invitational Ceramic Exhibition / Hanyang University Museum 2014. 2014 Exhibition of Korea Woman Ceramicist Association / Kyung-in Museum 2014.