Archaic Features in Masses by Morales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

The Concept of Polymediality

Marios Joannou Elia The Concept of Polymediality Literary Sources as an Inherent Polymedial Element of Music Veröffentlicht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Marios Joannou Elia The Concept of Polymediality Literary Sources as an Inherent Polymedial Element of Music Coverstreifen: Autosymphonic – Open-air multimedia symphony (2010–11), 360-degree positioning of musical groups Quelle: Marios Joannou Elia, m:con – mannheim:congress GmbH Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. 978-3-95983-100-0 (Paperback) 978-3-95983-101-7 (Hardcover) © 2017 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Nachdruck in jeder Form sowie die Wiedergabe durch Fernsehen, Rundfunk, Film, Bild- und Tonträger oder Benutzung für Vorträge, auch auszugsweise, nur mit Genehmigung des Verlags. Printed in Germany Abstract The commentary focuses on the predominantly applied extraneous media in my music, especially the inclusion of literary sources. The discourse begins with a succinct description of the concept of polymediali- ty, which involves two dimensions: the work-immanent compositional dimen- sion and polymediality in the process of staging (Chapter I). Chapter II considers literary sources as a constituent component of music’s polymediality. The first part is preoccupied with the implementation of textual elements and vocality in -

Petr Eben's Oratorio Apologia Sokratus

© 2010 Nelly Matova PETR EBEN’S ORATORIO APOLOGIA SOKRATUS (1967) AND BALLET CURSES AND BLESSINGS (1983): AN INTERPRETATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SYMBOLISM BEHIND THE TEXT SETTINGS AND MUSICAL STYLE BY NELLY MATOVA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Choral Music in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Donna Buchanan, Chair Professor Sever Tipei Assistant Professor David Cooper Assistant Professor Ricardo Herrera ABSTRACT The Czech composer Petr Eben (1927-2007) has written music in all genres except symphony, but he is highly recognized for his organ and choral compositions, which are his preferred genres. His vocal works include choral songs and vocal- instrumental works at a wide range of difficulty levels, from simple pedagogical songs to very advanced and technically challenging compositions. This study examines two of Eben‘s vocal-instrumental compositions. The oratorio Apologia Sokratus (1967) is a three-movement work; its libretto is based on Plato‘s Apology of Socrates. The ballet Curses and Blessings (1983) has a libretto compiled from numerous texts from the thirteenth to the twentieth centuries. The formal design of the ballet is unusual—a three-movement composition where the first is choral, the second is orchestral, and the third combines the previous two played simultaneously. Eben assembled the libretti for both compositions and they both address the contrasting sides of the human soul, evil and good, and the everlasting fight between them. This unity and contrast is the philosophical foundation for both compositions. -

Is Eastern Insulindia a Distinct Musical Area? L’Est Insulindien Est-Il Une Aire Musicale Distincte ?

Archipel Études interdisciplinaires sur le monde insulindien 90 | 2015 L’Est insulindien Is Eastern Insulindia a Distinct Musical Area? L’Est insulindien est-il une aire musicale distincte ? Philip Yampolsky Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/373 DOI: 10.4000/archipel.373 ISSN: 2104-3655 Publisher Association Archipel Printed version Date of publication: 15 October 2015 Number of pages: 153-187 ISBN: 978-2-910513-73-3 ISSN: 0044-8613 Electronic reference Philip Yampolsky , « Is Eastern Insulindia a Distinct Musical Area? », Archipel [Online], 90 | 2015, Online since 01 May 2017, connection on 14 November 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/ 373 ; DOI : 10.4000/archipel.373 Association Archipel PHILIP YAMPOLSKY 1 Is Eastern Insulindia a Distinct Musical Area? 1In this paper I attempt to distinguish the music of “eastern Insulindia” from that of other parts of Insulindia.2 Essentially this is an inquiry into certain musical features that are found in eastern Insulindia, together with a survey of where else in Insulindia they are or are not found. It is thus a distribution study, in line with others that have looked at the distribution of musical elements in Indonesia (Kunst 1939), the Philippines (Maceda 1998), Oceania (McLean 1979, 1994, 2014), and the region peripheral to the South China Sea (Revel 2013). With the exception of McLean, these studies have focused exclusively on material culture, namely musical instruments, tracing their geographical distribution and the vernacular terms associated with them. The aim has been to reveal cultural continuities and discontinuities and propose hypotheses about prehistoric settlement and culture contact in Insulindia and Oceania. -

Music of Latin America

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine Course Materials Open Educational Resources (OER) 01 Jun 2019 Music Appreciation: Music of Latin America Lorie L. Francis Missouri University of Science and Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/oer-course-materials Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Francis, Lorie L., "Music Appreciation: Music of Latin America" (2019). Course Materials. 3. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/oer-course-materials/3 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. This Course materials is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Course Materials by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Music Appreciation: Music of Latin America Lorie L. Francis, Associate Teaching Professor Class expectations What is this class all about?? Syllabus A printable version is located within canvas Quick overview of syllabus It is important to remember this is a blended class No class is held on Fridays Procedure for checking out a drum for practicing Rooms are only open certain hours Drums CANNOT be taken out of the building Best way to contact me is through email [email protected] Office hours are 1:00-2:00 Monday and Wednesday; -

The Collaborative Arrangements of Alice

THE COLLABORATIVE ARRANGEMENTS OF ALICE PARKER AND ROBERT SHAW by JAMES EDWARD TAYLOR JOHN RATLEDGE, COMMITTEE CHAIR DON FADER METKA ZUPANCIC SUSAN FLEMING KENNETH OZZELLO MARVIN JOHNSON A DOCUMENT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright James Edward Taylor 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This document is a comprehensive survey of the two hundred and twenty-three choral arrangements created in the collaboration between Alice Parker (b.1925) and Robert Shaw (1916-1999). This repertoire was written between 1950 and 1967 for seventeen RCA Victor recordings made by the Robert Shaw Chorale. Part I presents an overview of the music, title listings, and publisher information. Part II is a history of the collaboration, beginning with its genesis and the working relationship between the two. Their work occurred in the “Golden Age” of choral music in America and during the American folk music revival, both of which contributed to commercial album sales and the fame of Shaw and the Chorale. Part III describes the style of the arrangements, whose nineteen style characteristics are demonstrated in excerpts from six different songs. A detailed method developed by Dr. Parker for identifying distinguishing features of these arrangements is applied to one of the folk hymns. Over half of the Parker-Shaw arrangements are then compared in spreadsheets, found in Appendix III, with successive appendices presenting summaries of the results of the comparisons. This process reveals, among other things, the central role of melody and counterpoint in determining the nature of this music, and the arrangers’ preference for working with melodies based on traditional church modes and gapped scales over those with strong tonal implications. -

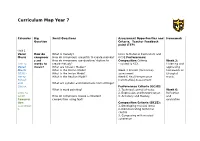

Curriculum Map Year 7

Curriculum Map Year 7 Calendar Big Small Questions Assessment Opportunities and Homework Question Criteria. Teacher Feedback point (TFP) Unit 1 Vocal How do What is melody? Links to National Curriculum and Music composer How do composers use pitch to create melody? GCSE Performance/ s set How do composers use duration/ rhythm to Composition Criteria Week 3: Link to words to create melody? – scaled to KS3. Listening and Vocal music? What are Scales / Modes? appraising Music What is the Dorian Mode? Week 3 interim (formative) homework on GCSE – What is the Ionian Mode? assessment Liturgical Henry What is the Aeolian Mode? Week 6 Final Performance music. Purcell (summative) Assessment and What are syllabic and melismatic text settings? Queen. Performance Criteria (GCSE): What is word painting? 1. Technical control of voice Week 6: Links to 2. Expression and Interpretation Reflection GCSE How do composers create a coherent 3. Accuracy and fluency and Composi composition using text? evaluation tion Composition Criteria (GCSE): coursewor 1. Developing musical ideas k. 2. Demonstrating technical control 3. Composing with musical coherence Unit 2 How do What are time signatures? Links to National Curriculum and Drummin composer What are simple time signatures? GCSE Performance/ g in s create What is common time? Composition Criteria Week 3: simple pieces What are the note durations/ rhythm patterns in – scaled to KS3. Listening and time using common time? appraising signatur percussio What are the correct hand positions for Week 3 interim (formative) homework on es n drumming simple rhythms? assessment African Link to instrumen What is homorhythm? Week 6 Final Performance drumming Fusions ts, rhythm What is polyrhythm? (summative) Assessment piece. -

West African Polyrhythm: Culture, Theory, and Representation1 Michael Frishkopf2 Department of Music, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

SHS Web of Conferences 102, 05001 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202110205001 ETLTC2021 West African Polyrhythm: 1 culture, theory, and representation Michael Frishkopf2 Department of Music, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Abstract. In this paper I explicate polyrhythm in the context of traditional West African music, framing it within a more general theory of polyrhythm and polymeter, then compare three approaches for the visual representation of both. In contrast to their analytical separation in Western theory and practice, traditional West African music features integral connections among all the expressive arts (music, poetry, dance, and drama), and the unity of rhythm and melody (what Nzewi calls “melo-rhythm”). Focusing on the Ewe people of south-eastern Ghana, I introduce the multi-art performance type called AgbeKor, highlighting its poly-melo-rhythms, and representing them in three notational systems: the well-known but culturally biased Western notation; a more neutral tabular notation, widely used in ethnomusicology but more limited in its representation of structure; and a context-free recursive grammar of my own devising, which concisely summarizes structure, at the possible cost of readability. Examples are presented, and the strengths and drawbacks of each system are assessed. While undoubtedly useful, visual representations cannot replace audio- visual recordings, much less the experience of participation in a live performance. 1 West African music as a holistic poly-kino-melo-rhythmic socio-cultural phenomenon Traditional West African music presents complex rhythmic and metric structures, through song, dance, and instrumental music – particularly (though by no means limited to) percussion music. This situation prevails, in particular, in Ghana cf [1, p. -

Hugo Distler (1908-1942)

HUGO DISTLER (1908-1942): RECONTEXTUALIZING DISTLER’S MUSIC FOR PERFORMANCE IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by Brad Pierson A dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Geoffrey P. Boers, Chair Giselle Wyers Steven Morrison Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music © Copyright 2014 Brad Pierson ii Acknowledgements It has been an absolute joy to study the life and music of Hugo Distler, and I owe a debt of gratitude to many people who have supported me in making this document possible. Thank you to Dr. Geoffrey Boers and Dr. Giselle Wyers, who have served as my primary mentors at the University of Washington. Your constant support and your excellence have challenged me to grow as a musician and as a person. Thank you to Dr. Steven Morrison and Dr. Steven Demorest for always having questions and forcing me to search for better answers. Joseph Schubert, thank you for your willingness to always read my writing and provide feedback even as you worked to complete your own dissertation. Thank you to Arndt Schnoor at the Hugo Distler Archive and to the many scholars whom I contacted to discuss research. Your thoughts and insights have been invaluable. Thank you to Jacob Finkle for working with me in the editing process and for your patience with my predilection for commas. Thank you to my colleagues at the University of Washington. Your friendship and support have gotten me through this degree. Finally, thank you to my family. You have always supported me in everything I do, and this journey would not have been possible without you. -

Style and Performance Considerations in Three Works Involving Flute by Joan Tower

Style and Performance Considerations in Three Works Involving Flute by Joan Tower: Snow Dreams , Valentine Trills , and A Little Gift by TAMMY EVANS YONCE (Under the Direction of Angela Jones-Reus and David Haas) ABSTRACT Joan Tower is a highly regarded contemporary composer who is known for her early serial style and subsequent organic style. Her compositional process is most frequently a collaborative one; a performer herself, she prefers to work with the musicians for whom she is writing. In addition to her Hexachords for solo flute (1972) and Flute Concerto (1989), which are her most commonly studied flute works, she has also written seventeen other chamber or solo works involving flute. This document contains a biography of the composer and an analysis of three chamber and solo works involving flute: Snow Dreams , Valentine Trills, and A Little Gift . A listing of Tower’s chamber and solo works involving flute and an interview with the composer are included as appendices. In addition to identifying formal aspects of the works, specific musical elements that are most salient to each work will be discussed. One of these elements in particular, density, will be analyzed in relation to how it creates or dispels intensity. Tower often employs the same compositional features in all three works to create this feeling of motion versus stasis, which is well illuminated through the analysis of the most salient musical elements. INDEX WORDS: Joan Tower, Snow Dreams , Valentine Trills , A Little Gift , A Gift, Flute, Chamber Music, Solo Music -

Darren Sigesmund Final Dissertation

Contrapuntally Inspired: Voice Leading, Texture and Rhythm in the Music of Ben Monder by Darren Thomas Sigesmund A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Darren Sigesmund 2021 Contrapuntally Inspired: Voice Leading, Texture and Rhythm in the Music of Ben Monder Darren Thomas Sigesmund Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2021 Abstract This dissertation examines the use of counterpoint in the music of New York guitarist Ben Monder, arguing that specific contrapuntal elements inform his musical expression and contribute to his unique voice in contemporary jazz. Published pedagogical literature on jazz composition emphasizes big band arranging over small ensemble writing and has not adequately addressed the scope of jazz compositional practices since the 1960s. Consequently, innovative approaches such as Monder’s have been neglected and suitable frameworks for analyzing his contributions have not been developed. Synthesizing Walter Piston’s notion of opposition and Ernst Toch’s interest in textural shifts as a form of contrast with attention to Monder’s development of intervallic voicings and voice leading broadens my framework for analyzing contemporary jazz counterpoint. In particular, my analysis emphasizes non-imitative polyphony consisting of opposing elements within a texture (melody, harmony, rhythm, metre) and contrast between textures (shifts). Score analysis, transcription and a personal interview with Monder form the basis for examining select compositions and related improvisations in solo, duo, trio or quartet settings featured in his ii recordings Flux (1996), Dust (1997), Excavation (2000), Oceana (2005), and Hydra (2013). -

Bernard Herrmann: Psycho

Bernard Herrmann: Psycho – ‘Prelude’, ‘The City’, ‘Marion’, ‘The Murder (Shower Scene)’, ‘The Toys’, ‘The Cellar’, ‘Discovery’, ‘Finale’ (for component 3: Appraising) Background information and performance circumstances The composer Bernard Herrmann (1911–75) was an American composer and conductor best known for his work on film scores such as Citizen Kane, Jason and the Argonauts, Fahrenheit 451 and Taxi Driver. He won an Academy Award (‘Oscar’) in 1941 for his score for The Devil and Daniel Webster. His name is particularly associated with the films of Alfred Hitchcock, scoring seven films between 1955 and 1966 (when Hitchcock rejected Hermann’s score for Torn Curtain). Of these, his scores for Psycho, North by Northwest and Vertigo are regarded as classics of the genre, Herrmann’s uncompromising music perfectly matching the twists and turns of Hitchcock’s filmmaking. (Herrmann was also ‘sound consultant’ for Hitchcock’s The Birds, where a musical score was replaced by electronically manipulated bird sounds.) Unlike the previous generation of film composers (who had all migrated from Europe, and whose musical styles were very much rooted in late 19th and early 20th century Romanticism), Herrmann was born in New York, studying at the Julliard School, and his influences were far more varied and modernist. He studied with Percy Grainger, loved the music of Delius, and, as a conductor, championed the music of the early American experimental composer Charles Ives. In fact, his early career was as a conductor and classical composer, and it was only after he began working with the actor/director Orson Welles that he turned to writing music, first for radio and then for films.