Provide More Recreation Page: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Park Director's Report (10/04/19)

Director’s Report STATE PARK SYSTEM ADVISORY COUNCIL Division of Parks and Recreation October 4, 2019 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE FY2020 Parks & Retail Comparative Statement (attached) covering period July 1, 2019 to Sept 12, 2019, has day use revenue at $5.064M, up 3.1% from the previous year. Cannon Mtn/FNSP is at $861K, up 12.8% and Hampton Meters is also starting strong at $1.277K, up 11.7% from the previous year. Parks retail is at $1.742K, up 5.1% from last year. Cannon/FNSP retail is strong at $224K, up 17.8% and Mt Washington has a strong start at $951K, up 35.4% from the previous year. FY2019 Parks & Retail Comparative Statement covering period July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019, with day use revenue closing at $10.148M up 0.7% from $10.075M the previous year. Cannon Mtn and Hampton Meters are both down by 3.1% and 3.5%, respectively. Parks retail closed on June 30, 2019, at $2.643M up 6% from the previous year. Cannon retail closed strong at $1.789M, up 11.9% from $1.598M in FY18. Mt Washington retail closed at $1.216M down 1.3% from the previous year. NH State Park Plate As of 08/31/19, there are 10,836 plates registered. FY2019 revenues earned are $854,185, with the greatest number of new plates (1,344) purchased within the fiscal year since the program’s start in 2012. From Jan 1 to Sept 22, 2019, a total of 44,526 park visitors (adults and youths) have entered state parks using the State Park Plate. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Integrating the MAPS Program Into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S

Integrating the MAPS Program into Coordinated Bird Monitoring in the Northeast (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5) A Report Submitted to the Northeast Coordinated Bird Monitoring Partnership and the American Bird Conservancy P.O. Box 249, 4249 Loudoun Avenue, The Plains, Virginia 20198 David F. DeSante, James F. Saracco, Peter Pyle, Danielle R. Kaschube, and Mary K. Chambers The Institute for Bird Populations P.O. Box 1346 Point Reyes Station, CA 94956-1346 Voice: 415-663-2050 Fax: 415-663-9482 www.birdpop.org [email protected] March 31, 2008 i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 3 METHODS ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Collection of MAPS data.................................................................................................................... 5 Considered Species............................................................................................................................. 6 Reproductive Indices, Population Trends, and Adult Apparent Survival .......................................... 6 MAPS Target Species......................................................................................................................... 7 Priority -

AUCTION Business News Barrow

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 6 JULY 8, 2010 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Living History In Albany: A Civil War Living History Encampment, featuring the 5th Massachusetts Battery, Light Artillery Army Of The Potomac, Inc., came to the Russell-Colbath Historic Homestead on the Kancamagus Highway in Albany on July 3 and 4.… A6 40 Years On Stage: The Mount Washington Valley Theater Company begins its 40th season with ‘The Music Man’ and the theater com- pany plans to engage, entertain and excite audiences this summer ... A7 Tin Mountain Nature Corner: Brake for moose, it could save your life! Learn fun facts about the third largest land animal in North America… A 28 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Page Two Can-Am Jericho ATV Festival A new kind of mud madness and family fun hen Jericho come. Any ATV or trail bike Mountain State that will be used only at the Park in Berlin event — that is, within Jericho became New Mountain State Park, the Cross- Hampshire’sW newest State Park, City Trail and the Success Trail it was designed to provide the — will not need a NH registra- first network of all-terrain vehi- tion during the Festival. We cle trails on state land in New hope that the event will spur rid- Hampshire. Now, with 50-plus ers to register their ATVs in miles of scenic trails and a new New Hampshire in the future, mud pit, the 7500-acre Park is as those registration dollars will set to host the Cam-Am Jericho directly impact future develop- ATV Festival on Saturday, July ment in the Park.” 10, from 8 a.m. -

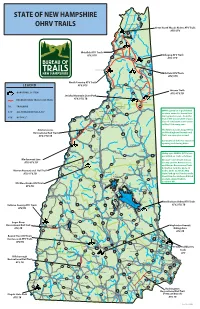

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

Appendix a Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There

Appendix A Places to Visit and Natural Communities to See There his list of places to visit is arranged by biophysical region. Within biophysical regions, the places are listed more or less north-to-south and by county. This list T includes all the places to visit that are mentioned in the natural community profiles, plus several more to round out an exploration of each biophysical region. The list of natural communities at each site is not exhaustive; only the communities that are especially well-expressed at that site are listed. Most of the natural communities listed are easily accessible at the site, though only rarely will they be indicated on trail maps or brochures. You, the naturalist, will need to do the sleuthing to find out where they are. Use topographic maps and aerial photographs if you can get them. In a few cases you will need to do some serious bushwhacking to find the communities listed. Bring your map and compass, and enjoy! Champlain Valley Franklin County Highgate State Park, Highgate Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation Temperate Calcareous Cliff Rock River Wildlife Management Area, Highgate Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Alder Swamp Missisquoi River Delta, Swanton and Highgate Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Protected with the assistance of The Nature Conservancy Silver Maple-Sensitive Fern Riverine Floodplain Forest Lakeside Floodplain Forest Red or Silver Maple-Green Ash Swamp Pitch Pine Woodland Bog -

Exhibit B White Mountain National Forest

72°00'00" 71°52'30" 71°45'00" 71°37'30" 71°30'00" 71°22'30" 71°15'00" 71°07'30" 71°00'00" 70°52'30" 70°45'00" 72°15'00" 72°07'30" 72°00'00" ERROL 11 MILES S T R A T F O R D Victor NORTH STRATFORD 8 MILES Head Bald Mtn PIERMONT 4.6 MI. Jimmy Cole 2378 16 /(3 Ledge Ä( 10 Hill Ä( 1525 D U M M E R Dummer Cem Potters 44° Sunday Hill Mtn Ledge 44° 37' Blackberry 1823 Percy 37' 25A 30" Dame Hill Ä( Ä(110 30" SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN Cem Morse Mtn Dickey Bickford 1925 Airstrip Hill Crystal Hill Beach 2067 25A Hill 65 Cummings 25A Ä( Mt Cube 110 TRAIL CORRIDOR Ä( Orfordville 2909 Devils Mtn Ä(A 1209 O R O FO R D 110 Moore Slide Ä( Mtn 43° TRAIL Groveton 1700 SOUTH Location ST. JOHNSBERRY 44 MI. Strawberry 43° Stark Hill 52' HEXACUBA POND West Milan Closton Hill "!9 Covered Bridge 1843 30" 52' 110 Hill !t A Peabody Covered Bridge 30" Mill Mtn Ä( Hill CO Quinttown GILMANSMI. CORNER 0.6 Substa 2517 10 Bundy CO 110 Ä( Kenyon Mountain Eastman Ledges Ä( Hill 2665 S T A R K Horn Hill Hill Stonehouse 2055 Jodrie MILAN HILL Mountain 11 91 Brick Hill Milan Hol 1986 110 ¦¨§ Cem Milan Hill B North Mousley Ä( Lookout 1737 Thetford Mountain 2008 Cape Horn MILAN HILL Skunk Lampier /(5 STATE PARK Moody Hill TRAIL M I L A N Mountain Northumberland North Square Smith Mtn Hardscrabble 1969 Peak Green Post Hill Mountain 2735 Ledge 2213 Beech NANSEN 3 Hutchins 2804 Rogers ORANGE /( Hill Mtn Ledge SKI JUMP GRAFTON The Pinnacle Smarts Hodgoon UNKNOWN 3500 Lookout "!9 Mountain N O R T H U M B E R L A N D 3730 Hill Demmick HIll 2909 ROGERS LEDGE Round < MILL Acorn 1583 ! Mtn THETFORD 0.7 MI. -

N.H. State Parks

New Hampshire State Parks WELCOME TO NEW HAMPSHIRE Amenities at a Glance Third Connecticut Lake * Restrooms ** Pets Biking Launch Boat Boating Camping Fishing Hiking Picnicking Swimming Use Winter Deer Mtn. 5 Campground Great North Woods Region N K I H I A E J L M I 3 D e e r M t n . 1 Androscoggin Wayside U U U U Second Connecticut Lake 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside U U U U STATE PARKS Connecticut Lakes Headwaters 3 Coleman State Park U U U W U U U U U 4 Working Forest 4 Connecticut Lakes Headwaters Working Forest U U U W U U U U U Escape from the hectic pace of everyday living and enjoy one of First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods 5 Deer Mountain Campground U U U W U U U U U New Hampshire’s State Park properties. Just think: Wherever Riders 3 6 Dixville Notch State Park U U U U you are in New Hampshire, you’re probably no more than an hour Pittsbur g 9 Lake Francis 7 Forest Lake State Park U W U U U U from a New Hampshire State Park property. Our state parks, State Park 8 U W U U U U U U U U U Lake Francis Jericho Mountain State Park historic sites, trails, and waysides are found in a variety of settings, 9 Lake Francis State Park U U U U U U U U U U ranging from the white sand and surf of the Seacoast to the cool 145 10 Milan Hill State Park U U U U U U lakes and ponds inland and the inviting mountains scattered all 11 Mollidgewock State Park U W W W U U U 2 Beaver Brook Falls Wayside over the state. -

North Maine Woods2013 $3

experience the tradition North Maine Woods2013 $3 On behalf welcomeof the many families, private corporations, conservation organizations and managers of state owned land, we welcome you to this special region of Maine. We’re proud of the history of this remote region and our ability to keep this area open for public enjoyment. In addition to providing remote recreational opportunities, this region is also the “wood basket” that supports our natural resource based economy of Maine. This booklet is designed to help you have a safe and enjoyable trip to the area, plus provide you with important information about forest resource management and recreational use. P10 Katahdin Ironworks Jo-Mary Forest Information P14 New plan for the Allagash Wilderness Waterway P18 Moose: Icon of P35 Northern Region P39 Sharing the roads the North Woods Fisheries Update with logging trucks 2013 Visitor Fees NMW staff by photo RESIDENT NON-RESIDENT Under 15 .............................................................. Free Day Use & Camping Age 70 and Over ............................................... Free Day Use Per Person Per Day ...................................................$7 ................ $12 Camping Per Night ....................................................$10 ............. $12 Annual Day Use Registration ...............................$75 ............. N/A Annual Unlimited Camping ..................................$175 .......... N/A Checkpoint Hours of Operation Camping Only Annual Pass ...................................$100 .......... $100 Visitors traveling by vehicle will pass through one of the fol- lowing checkpoints. Please refer to the map in the center of Special Reduced Seasonal Rates this publication for locations. Summer season is from May 1 to September 30. Fall season is from August 20 to November 30. Either summer or fall passes NMW Checkpoints are valid between August 20 and September 30. Allagash 5am-9pm daily Caribou 6am-9pm daily Seasonal Day Use Pass ............................................$50 ............ -

Winter 2020 Long Trail News

NEWS Quarterly of the Green Mountain Club WINTER 2020 Codding Hollow Property Conserved | Managing Trails During a Global Pandemic | Winter Hiking Safety Side-to-Side in Less Than a Week | Skiing Vermont’s Highest Peaks CONTENTS Winter 2020, Volume 80, No. 3 The mission of the Green Mountain Club is to make the Vermont mountains play a larger part in the life of the people by protecting and maintaining the Long Trail System and fostering, through education, the stewardship of Vermont’s hiking trails and mountains. Quarterly of the Green Mountain Club Michael DeBonis, Executive Director Alicia DiCocco, Director of Development & Communications PHOTO BY ALICIA DICOCCO Becky Riley and Hugh DiCocco on Mt. Mansfield Ilana Copel, Communications Assistant Richard Andrews, Volunteer Copy Editor Sylvie Vidrine, Graphic Designer FEATURES Green Mountain Club 4711 Waterbury-Stowe Road ❯ Waterbury Center, Vermont 05677 6 Celebrating Success after 34 years: Phone: (802) 244-7037 Codding Hollow Property Conserved Fax: (802) 244-5867 E-mail: [email protected] by Mollie Flanigan Website: greenmountainclub.org ❯ The Long Trail News is published by The 10 Managing Trails During a Global Pandemic: Green Mountain Club, Inc., a nonprofit Field Staff Reflections of the 2020 Season organization founded in 1910. In a 1971 Joint Resolution, the Vermont Legislature by John Plummer designated the Green Mountain Club the “founder, sponsor, defender and protector of 12 ❯ Hiking Trails During a Global Pandemic: the Long Trail System...” Hiker Reflections of the 2020 Season Contributions of manuscripts, photos, illustrations, and news are welcome from by Rick Dugan members and nonmembers. ❯ The opinions expressed byLTN contributors 16 Going the Distance: are not necessarily those of GMC. -

THE FLAVOR of the GRAND NORTH Experience North Ern N Ew Hampshire’S Culinary Delights with Th Ese Recipes TABLE of CONTENTS

THE FLAVOR OF THE GRAND NORTH Experience north ern N ew Hampshire’s culinary delights with th ese recipes TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................3 BREAKFAST Bear Rock Adventures No-Bake Pumpkin Breakfast Bites ......................................................................................................4 Omni Mount Washington Resort Raspberry Stuffed French Toast ........................................................................................5 Rek’-Lis Brewing Company Coconut Chai Granola ...............................................................................................................6 BEVERAGES The Granite Grind Franconia Frenzy ......................................................................................................................................7 Mount Washington Cog Railway Keep ‘Em Warm! Mulled Cider ........................................................................................8 Potato Barn Antiques Cranberry Cosmo ...............................................................................................................................9 Raft NH Cowboy Coffee ......................................................................................................................................................10 BREAD/SALAD/SOUP Appalachian Mountain Club High Huts Cheese and Garlic Bread .....................................................................................11 -

Seboomook Unit Management Plan

Seboomook Unit Management Plan Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands March 2007 Table of Contents Acknowledgements I. Introduction 1 About This Document 1 What is the Seboomook Unit? 2 II. The Planning Process 4 Statutory and Policy Guidance 4 Public Participation 4 III. The Planning Context 6 Acquisition History 6 Relation to North Maine Woods 6 Parks and Lands Overlap 8 Public-Private Partnerships 8 New Water-Based Recreation Opportunities 9 Remote Location 10 Public Recreation Resources in the Broader Region 10 New Regional Recreation Opportunities - Public/Private Initiatives 16 Trends in Recreation Use 18 Summary of Planning Implications 19 IV. The Character and Resources of the Unit 20 Overview 20 Seboomook and Canada Falls Parcels 24 St. John Ponds Parcel 46 Baker Lake Parcel 52 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 60 V. A Vision for the Unit 66 VI. Resource Allocations 69 Overview Summary 69 Seboomook Lake Parcel 82 Canada Falls Parcel 85 Baker Lake Parcel 86 St. John Ponds Parcel 88 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 89 VII. Management Recommendations 90 Seboomook and Canada Falls Parcels 90 St. John Ponds Parcel 95 Baker Lake Parcel 95 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 97 VIII. Monitoring and Evaluation 98 IX. Appendices A. Advisory Committee Members B. Summary of Management Issues C. Bureau Response to Written Public Comments D. Deed Restrictions and Agreements E. Guiding Statutes F. Glossary i G. References H. Natural Resource Inventory of the Bureau of Parks and Lands Seboomook Unit (under separate cover) I. Timber Harvest