Seboomook Unit Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Assembly, • 1933

THE 12th April, 1933 :"'EGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY DEBATES (OFFICIAL REPORT) VOLUME! IV, 1933 . (3161 MII,.dJ 10 1~1" A.pril, 19.1.1) FOURTH SESSION : OF THE , FIFTH· LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, • 1933 SIMLA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS 1933 16 Legislative Assembly. President : Tn HONOURABLE Sla IBRAHIM: R.umlroou., K.C.S.I., C.I.E. (Upto 7th March, 1933.) THE HONOuWLE MR. R. K. SHANKUKHAJI Cm:lTY. (From 14th March, 1933.) Deputy Preaitknt : lIB. R. K. SBANMtJKlIAM CoTTY, M.L.A. (Upto 13th March, 1933.) Ma. ABDUL lIATIN CluUDHURY, M.L.A. (From 22nd March, 1933.) Panel of 01uJirmen : SIR HAItI SINGH GoUB, KT., M.L.A. SIR ABDUB RAHIM, K.C.S.I., KT., M.L.A. SIR LEsLIE HUDSON, KT., M.L.A . •. MOB.uouD YAMIN KHAN, C.I.E., M.L.A. Secretary : MR. S. C. GUPl'A, C.I.E., BAIt.-AT-LAW. A,Bi8taf1t8 of1M 8ecretMy : III..uJ )JURAXMAD RAII'I, B..u.-AT-LAW. RAI BAJIADUB D. DU'IT. Ma,,1Ial: CAPTAIN HAJI SAltDAIt NUB AHMAD KHAN, M.C., I.O.M., I.A. Oommittee Oft Pvhlic PetittonB : , Ma. R. K. SlIANMUKlWI COTTY, M.L.A., Ohairman. (Upto to 13th March, 1933.) MR. ABDUL MA:nN CHAUDHURY, M.L.A., Ohairman. (From 221ld March, 1933.) Sm LESLIE HUDSON, KT., M.L.A. , Sm ABnULLA.-AL-M.1xuN SUHRAWAltDY, KT., M.L.A. Ma. B. SITUAMARAJU, M.L.A. MR. C. S. RANGA IUB, M.L.A. 17 CONTENTS. VOLUME IV.-31st Maroh to 12th April, 1933. PA01ll8. P'BIDAY, 31ST' MaCH, 1933- F'aIDAY, 7TH APBIL, 1933- Unstarred Questionse.nd Answers 2893--2004 Members Sworn 3229 Statement of Business Questions and Answers 3229---43 Statements laid on the Table Statements laid on the Table 3243-53 Proposals for Indian Constitu- tional Reform-Adopted 290~78 The Provincial Crimind Law Sup- plementing Bill-Pa.ssed as TURDAY, 1ST APRn., 1933- amended 3254-68 Ouestiol18 and Answers . -

Workshop on Revitalization of Indigenous Architecture and Traditional Building Skills

• h _. Workshop on Revitalization oflndigenous Architecture and Traditional Building Skills final report Workshop on Revitalization of Indigenous Architecture and Traditional Building Skills In collaboration with the Government of Samoa and the International Training Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region under the auspices of UNESCO (CRIHAP) Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and UNESCO Apia Office © UNESCO 2015 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco. org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Open Access is not applicable to non-UNESCO copyright photos in this publication. Project Coordinator: Akatsuki Takahashi Cover photo: Fale under construction at Samoa Culture Centre / © -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

River Related Geologic/Hydrologic Features Abbott Brook

Maine River Study Appendix B - River Related Geologic/Hydrologic Features Significant Feature County(s) Location Link / Comments River Name Abbott Brook Abbot Brook Falls Oxford Lincoln Twp best guess location no exact location info Albany Brook Albany Brook Gorge Oxford Albany Twp https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/14676 Allagash River Allagash Falls Aroostook T15 R11 https://www.worldwaterfalldatabase.com/waterfall/Allagash-Falls-20408 Allagash Stream Little Allagash Falls Aroostook Eagle Lake Twp http://bangordailynews.com/2012/04/04/outdoors/shorter-allagash-adventures-worthwhile Austin Stream Austin Falls Somerset Moscow Twp http://www.newenglandwaterfalls.com/me-austinstreamfalls.html Bagaduce River Bagaduce Reversing Falls Hancock Brooksville https://www.worldwaterfalldatabase.com/waterfall/Bagaduce-Falls-20606 Mother Walker Falls Gorge Grafton Screw Auger Falls Gorge Grafton Bear River Moose Cave Gorge Oxford Grafton http://www.newenglandwaterfalls.com/me-screwaugerfalls-grafton.html Big Wilson Stream Big Wilson Falls Piscataquis Elliotsville Twp http://www.newenglandwaterfalls.com/me-bigwilsonfalls.html Big Wilson Stream Early Landing Falls Piscataquis Willimantic https://tinyurl.com/y7rlnap6 Big Wilson Stream Tobey Falls Piscataquis Willimantic http://www.newenglandwaterfalls.com/me-tobeyfalls.html Piscataquis River Black Stream Black Stream Esker Piscataquis to Branns Mill Pond very hard to discerne best guess location Carrabasset River North Anson Gorge Somerset Anson https://www.mindat.org/loc-239310.html Cascade Stream -

Chronicle Spring 2017

2017 President’s Notes 485 Chewonki Neck Road Wiscasset, Maine 04578-4822 he famed naturalist Roger Tory Peterson popularized Tel: (207) 882-7323 nature study for millions of people with his first book, Fax: (207) 882-4074 Email: [email protected] A Field Guide to the Birds, which he wrote and illustrated Web: chewonki.org during his years as a staff member at Chewonki. Peterson Chewonki inspires artfully combined the scientific method with a reverence transformative growth, Tfor the natural world. Inspired by his work and that of scores of other teaches appreciation and science educators who have taught at Chewonki over the past 102 years, stewardship of the natural we try, day in and day out, to encourage children and young adults to world, and challenges people observe the world around them, ask good questions, and develop to build thriving, sustainable evidence-based conclusions. communities throughout Nature provides vivid lessons about the importance of getting your their lives. facts straight. A canoe pushed broadside against a rock will flip if the current is too strong. At Chewonki, we ask young people to study the situation, determine what needs to be done, and work with others to design and execute solutions. We encourage them to CONTENTS use judgment tempered by experience and information. They soon realize that ignoring evidence 2 News results in bad outcomes. 6 Susan Feibelman For most of my life, I assumed that scientific principles would play an increasingly more 9 Value of Studying History important role in education and decision-making affecting society as a whole. -

Storied Lands & Waters of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway

Part Two: Heritage Resource Assessment HERITAGE RESOURCE ASSESSMENT 24 | C h a p t e r 3 3. ALLAGASH HERITAGE RESOURCES Historic and cultural resources help us understand past human interaction with the Allagash watershed, and create a sense of time and place for those who enjoy the lands and waters of the Waterway. Today, places, objects, and ideas associated with the Allagash create and maintain connections, both for visitors who journey along the river and lakes, and those who appreciate the Allagash Wilderness Waterway from afar. Those connections are expressed in what was created by those who came before, what they preserved, and what they honored—all reflections of how they acted and what they believed (Heyman, 2002). The historic and cultural resources of the Waterway help people learn, not only from their forebears, but from people of other traditions too. “Cultural resources constitute a unique medium through which all people, regardless of background, can see themselves and the rest of the world from a new point of view” (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1998, p. 49529). What are these “resources” that pique curiosity, transmit meaning about historical events, and appeal to a person’s aesthetic sense? Some are so common as to go unnoticed—for example, the natural settings that are woven into how Mainers think of nature and how others think of Maine. Other, more apparent resources take many forms—buildings, material objects of all kinds, literature, features from recent and ancient history, photographs, folklore, and more (Heyman, 2002). The term “heritage resources” conveys the breadth of these resources, and I use it in Storied Lands & Waters interchangeably with “historic and cultural resources.” Storied Lands & Waters is neither a history of the Waterway nor the properties, landscapes, structures, objects, and other resources presented in chapter 3. -

Experience Maine's Katahdin Region

Experience Maine’s Katahdin Region An easy ride up I-95 Guided moose and wildlife tours Whitewater rafting Camping, cabins, and luxury lodging Spectacular views Fine dining and light fare Fishing, hiking and relaxing www.neoc.com 1-800-766-7238 Katahdin Region... everything Whatever your passion for the ou PLUS the magnificent backdrop o View of Mt. Katahdin from Twin Pines on Millinocket Lake www.neoc.com 1-800-766-7238 outdoor adventurers want utdoors, you can have it all of Mt. Katahdin. Whitewater Rafting Family Float Trips Moose Tours Kayak Instruction Guided Fishing Hiking Snowmobiling Cross Country Skiing Weddings Family Reunions Corporate Retreats and much more... www.neoc.com 1-800-766-7238 Raft Maine’s Scenic Rivers From a mellow Class I to a challenging Class V, it's easy to plan a family rafting trip or whitewater rafting vacation for groups, couples, and individuals seeking a broad range of experiences. www.neoc.com 1-800-766-7238 MAINE’S SCENIC RIVERS Whatever your expectations, THE PENOBSCOT Lower river trips or anticipate more soft adventure/family trips. The Penobscot River: A pool-drop river with spectacular, complex Ages 6 and up. rapids dropping into calm pools of water which allow time to catch your breath before tackling the next rapid. The 90 foot walls of Full river for high adventure Ripogenus Gorge give way to breathtaking views of the mountains of trips including some advanced Baxter Park including Mt. Katahdin, Maine’s highest Class V rapids. mountain. Surfing spots and a natural water slide Age 15 and up. -

ALLAGASH MAINE BUREAU of PARKS and LANDS WILDERNESS the Northward Natural Flow of Allagash Waters from Telos Lake to the St

ALLAGASH AND LANDS MAINE BUREAU OF PARKS WILDERNESS The northward natural flow of Allagash waters from Telos Lake to the St. John River presented a challenge to Bangor landowners and inves- WATERWAY tors who wanted to float logs from land around Chamberlain and Telos By Matthew LaRoche lakes southward to mills along the Penobscot River. So, they reversed the flow by building two dams in 1841. magnificent 92-mile-long ribbon of interconnected lakes, CHURCHILL DAM raised the water ponds, rivers, and streams flowing through the heart of MAHOOSUC GUIDE SERVICE level and Telos Dam controlled the Maine’s vast northern forest, the Allagash Wilderness water release and logs down Webster Waterway (AWW) features unbroken shoreline on the Stream and eventually to Bangor. headwater lakes and free-flowing river along the lower Chamberlain Dam was later modified waterway. The AWW’s rich culture includes use by to include a lock system so that logs Indigenous people for millennia and a colorful logging history. cut near Eagle Lake could be floated to the Bangor lumber market. In 1966, the Maine Legislature established the AWW to preserve, The AWW provides visitors with a true wilderness experience, with limited protect, and enhance this unique area’s wilderness character. vehicle access and restrictions on motorized watercraft. Some 100 primitive Four years later, the AWW garnered designation as a wild river campsites dot the shorelines, and anglers from all over New England come to LAROCHE MATT THE TRAMWAY HISTORIC in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSR). This the waterway in the spring and fall to fish for native brook trout, whitefish, and DISTRICT, which is listed on the year marks 50 years of federal protection under the NWSR Act. -

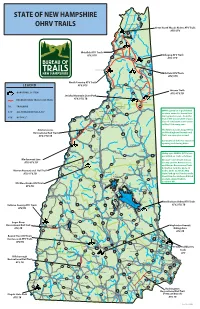

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

North Maine Woods2013 $3

experience the tradition North Maine Woods2013 $3 On behalf welcomeof the many families, private corporations, conservation organizations and managers of state owned land, we welcome you to this special region of Maine. We’re proud of the history of this remote region and our ability to keep this area open for public enjoyment. In addition to providing remote recreational opportunities, this region is also the “wood basket” that supports our natural resource based economy of Maine. This booklet is designed to help you have a safe and enjoyable trip to the area, plus provide you with important information about forest resource management and recreational use. P10 Katahdin Ironworks Jo-Mary Forest Information P14 New plan for the Allagash Wilderness Waterway P18 Moose: Icon of P35 Northern Region P39 Sharing the roads the North Woods Fisheries Update with logging trucks 2013 Visitor Fees NMW staff by photo RESIDENT NON-RESIDENT Under 15 .............................................................. Free Day Use & Camping Age 70 and Over ............................................... Free Day Use Per Person Per Day ...................................................$7 ................ $12 Camping Per Night ....................................................$10 ............. $12 Annual Day Use Registration ...............................$75 ............. N/A Annual Unlimited Camping ..................................$175 .......... N/A Checkpoint Hours of Operation Camping Only Annual Pass ...................................$100 .......... $100 Visitors traveling by vehicle will pass through one of the fol- lowing checkpoints. Please refer to the map in the center of Special Reduced Seasonal Rates this publication for locations. Summer season is from May 1 to September 30. Fall season is from August 20 to November 30. Either summer or fall passes NMW Checkpoints are valid between August 20 and September 30. Allagash 5am-9pm daily Caribou 6am-9pm daily Seasonal Day Use Pass ............................................$50 ............ -

Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game

Maine State Library Digital Maine Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books Inland Fisheries and Wildlife 4-22-1939 Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books Recommended Citation Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Game, "Maine Inland Ice Fishing Laws : 1939 Revision" (1939). Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books. 66. https://digitalmaine.com/ifw_law_books/66 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Inland Fisheries and Wildlife at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Law Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Y v Maine INLAND ICE FISHING LAWS 19 3 9 REVISION ICE FISHING LAWS The waters* listed by Counties, in this pamphlet are separated into groups which are governed by the same laws GENERAL LAW Except as otherwise specified herein, it Is illegal to fish bai_any_Jtmd_^f_fish_Jn^va2er«_»vhicli_are_closed^o_fishin^ for salmon, trout and togue. Bass cannot be taken through tTTT ice at any time, Persons properly licensed may fish through the ice in the daytime with 5 set lines each, when under the immediate supervision of the person fishing, and *n the night-time for cusk in such waters as are open forfiah- ing in the night time for cusk. Non-residents over 10 years of age and residents over 18 years of age must be licensed. Sec, 27. Fishing for gain or hire prohibited! exceptions! JMialty. Whoever shall, for the whole or any part of the time, engage in the business or occupation of fishing in any of the inland waters of the state above tide-waters, for salmon, togue, trout, black bass, pickerel, or white perch, for gain or hire, shall for every such offense pay a fine of $50 and costs, except that pickerel legally taken in the County of Washington may be sold by the person tak ing the same. -

Water Column a Publication of the Maine Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program

the Water Column A Publication of the Maine Volunteer Lake Monitoring Program Vol. 18, No. 1 Fall 2013 CITIZEN LAKE SCIENTISTS Their Vital Role in Monitoring & Protecting Maine Lakes What’s Inside President's Message . 2 President’s Lakeside Notes: Citizen Lake Scientists . 3 Littorally Speaking: Moosehead Survey . 4 Quality Counts: Certification & Data Credibility . 6 Chinese Mystery Snails . 7 Message Is The Secchi Disk Becoming Obsolete? . 8 Bill Monagle IPP Season in Review . 9 President, VLMP Board of Directors The VLMP Lake Monitoring Advantage . 10 Thank You Donors! . 12 2013 VLMP Annual Conference . 14 In The Wake of Thoreau... Welcome New Monitors! . 16 n a recent sunny and calm autumn what he could not see. An interesting Camp Kawanhee Braves High Winds . 17 afternoon while sipping tea with a perspective, wouldn’t you agree? VLMP Advisory Board Welcomes New Members . 18 O friend (well, one of us was sipping tea) How Do You Monitor Ice-Out? . 19 I am sharing this with you because on the dock of her lakeside home on 2013 Interns . .20 & 22 while my friend and I were enjoying Cobbossee Lake, and marveling at the Passings . 21 our refreshments and conversation, splendor before us, my friend remarked, Notices . 22 my thoughts went directly to the many ‘as a limnologist, I gather you see things volunteer lake monitors and invasive that the average observer cannot when plant patrollers of the Maine VLMP, looking out over a lake.' Well, that may and how essential your contributions be partly true. Having been involved are to more fully documenting and in lake science for over thirty years, I understanding the condition of many can speculate about what is occurring of Maine’s lakes and ponds.