Euripides' Bakkhai and the Colonization of Sophrosune: a Translation with Commentary Shannon K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IDF-Report 84 | 1 Dow & Ngiam

IDF International Dragonfly Fund - Report Journal of the International Dragonfly Fund 1-31 Rory A. Dow & Robin W.J. Ngiam Odonata from two areas in the Upper Baram in Sarawak: Sungai Sii and Ulu Moh Published 20.07.2015 84 ISSN 1435-3393 The International Dragonfly Fund (IDF) is a scientific society founded in 1996 for the improvement of odonatological knowledge and the protection of species. Internet: http://www.dragonflyfund.org/ This series intends to publish studies promoted by IDF and to facilitate cost-efficient and rapid dissemination of odonatological data. Editorial Work: Martin Schorr, Milen Marinov Layout: Bernd Kunz Indexed by Zoological Record, Thomson Reuters, UK Home page of IDF: Holger Hunger Impressum: International Dragonfly Fund - Report - Volume 84 Publisher: International Dragonfly Fund e.V., Schulstr. 7B, 54314 Zerf, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Responsible editor: Martin Schorr Printed by ColourConnection, Frankfurt am Main. www.printweb.de Published: 20.07.2015 Odonata from two areas in the Upper Baram in Sarawak: Sungai Sii and Ulu Moh Rory A. Dow1 & Robin W.J. Ngiam2 1Naturalis Biodiversity Center, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands <[email protected]> 2National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569, Republic of Singapore <[email protected]> Abstract Records of Odonata from two areas in the upper Baram area in Sarawak’s Miri Division are presented. Sixty five species are recorded from the Sungai Sii area and sixty three from the Ulu Moh area. Notable records include Telosticta ulubaram, Coeliccia south- welli, Leptogomphus new species, Macromia corycia and Tramea cf. -

Honey Plays a Significant Role in the Mythology and History of Many

Rhododendron Ponticum Rhodora! if the sages ask thee why This charm is wasted on the earth and sky, Tell them, dear, that if eyes were made for seeing, Then beauty is its own excuse for being R.W. Emerson, ‘The Rhodora’ "The Delphic priestess in historical times chewed a laurel leaf but when she was a Bee surely she must have sought her inspiration in the honeycomb." Jane Ellen Harrison, Prologemena to Greek Religion Thy Lord taught the Bee To build its cells in hills, On trees and in man’s habitations; Then to eat of all The produce of the earth . From within their bodies comes a drink of varying colors, Wherein is healing for mankind. The Holy Koran 1 Mad Honey Contents Point of View and Introduction 4 A summary of the material 5 What the Substance is 7 A History of Honey a very short history of the relationship of humans and honey A Cultural History of Toxic Honey 9 mad honey in ancient Greece Mad Honey in the New World 10 the Americas and Australasia How the substance works 11 Psychopharmacology selected outbreaks symptoms external indicators and internal registers substances neurophysiological action medical treatment How the substance was used 13 Honied Consciousness: the use of toxic honey as a consciousness altering substance ancient Greece Daphne and Delphi Apollo and Daphne Rhododendron and Laurel Appendix 1 21 Classical References (key selections from the texts) -Diodorus Siculus -Homeric Hymns -Longus -Pausanias -Pliny The Elder -Xenephon Appendix II 29 More on Mellissa Appendix lll 30 Source of the Substances Botany and Sources of Grayanotoxin 2 Appendix lV 32 Honey and Medicine Ancient and Modern Appendix V 34 The Properties of Ethelyne Appendix Vl 36 Entrances: Food, Drink and Enemas Bibliography 39 3 Mad Honey Point of View and Introduction It’s no surprise to discover that honey, and the bees that produce it, play a notable role in mythology and religion throughout the world. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA. -

In the Art of Sandro Botticelli And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ANTIQUITY AND THE SISTINE SOJOURN (1481-1482) IN THE ART OF SANDRO BOTTICELLI AND DOMENICO GHIRLANDAIO Volume 1 A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Max Calvin Marmor May, 1982 ~ • I The Thesis of Max Calvin Marmor is approved: anne L. Trabold, Ph.D. California State University, Northridge i i This thesis is dedicated to the immortal words of Ibn Abad Sina "Seek not gold in shallow vessels!" (Contra Alchemia, Praefatio) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due my thesis committee for allowing a maverick to go his own way. Without their contributions, this experience would not have been what it has been. More could be said on this score but, to quote the Devil (whose advice I should have followed from the outset): "Mach es kurz! Am Juengsten Tag ist's nur ein F--z!" So I'll "make it short." I owe special thanks to Dr. Birgitta Wohl, who initially persuaded me that higher education is worthwhile; who expressed unfailing interest in my ideas and progress; and who, throughout, has provided a unique living example of wide learning and humanistic scholarship. Finally, this thesis could not have been written without the ever prompt, ever courteous services of the CSUN Library Inter-Library Loan Department. Thanks to Charlotte (in her many roles}, to Misha and their myriad elves, who, for an unconscionably long time, made every day Christmas! iv CONTENTS Page LIST 01'' FIGURES . vii ABSTRACT . ix Chapter INTRODUCTION: CONTEXT AND CRISIS IN THE REVIVAL OF ANTIQUITY. -

A SKELETON CHECKLIST of the BUTTERFLIES of the UNITED STATES and CANADA Preparatory to Publication of the Catalogue Jonathan P

A SKELETON CHECKLIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA Preparatory to publication of the Catalogue © Jonathan P. Pelham August 2006 Superfamily HESPERIOIDEA Latreille, 1809 Family Hesperiidae Latreille, 1809 Subfamily Eudaminae Mabille, 1877 PHOCIDES Hübner, [1819] = Erycides Hübner, [1819] = Dysenius Scudder, 1872 *1. Phocides pigmalion (Cramer, 1779) = tenuistriga Mabille & Boullet, 1912 a. Phocides pigmalion okeechobee (Worthington, 1881) 2. Phocides belus (Godman and Salvin, 1890) *3. Phocides polybius (Fabricius, 1793) =‡palemon (Cramer, 1777) Homonym = cruentus Hübner, [1819] = palaemonides Röber, 1925 = ab. ‡"gunderi" R. C. Williams & Bell, 1931 a. Phocides polybius lilea (Reakirt, [1867]) = albicilla (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) = socius (Butler & Druce, 1872) =‡cruentus (Scudder, 1872) Homonym = sanguinea (Scudder, 1872) = imbreus (Plötz, 1879) = spurius (Mabille, 1880) = decolor (Mabille, 1880) = albiciliata Röber, 1925 PROTEIDES Hübner, [1819] = Dicranaspis Mabille, [1879] 4. Proteides mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) a. Proteides mercurius mercurius (Fabricius, 1787) =‡idas (Cramer, 1779) Homonym b. Proteides mercurius sanantonio (Lucas, 1857) EPARGYREUS Hübner, [1819] = Eridamus Burmeister, 1875 5. Epargyreus zestos (Geyer, 1832) a. Epargyreus zestos zestos (Geyer, 1832) = oberon (Worthington, 1881) = arsaces Mabille, 1903 6. Epargyreus clarus (Cramer, 1775) a. Epargyreus clarus clarus (Cramer, 1775) =‡tityrus (Fabricius, 1775) Homonym = argentosus Hayward, 1933 = argenteola (Matsumura, 1940) = ab. ‡"obliteratus" -

Parnassus, Delphi, and the Thyiades Mcinerney, Jeremy Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1997; 38, 3; Proquest Pg

Parnassus, Delphi, and the Thyiades McInerney, Jeremy Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1997; 38, 3; ProQuest pg. 263 Parnassus, Delphi, and the Thyiades Jeremy McInerney AN INTERNATIONAL SANCTUARY, Delphi helped bring a bout the transition within the emerging poleis of the ~ Archaic period to what Fran~ois de Polignac has called a "more finished, <adult' stage of society and institutions. "1 Delphi's business was international in scope: the sanctuary was involved in colonization, arbitration, and panhellenism.2 Yet one important aspect of Delphi's emergence as a panhellenic sanc tuary rarely studied is the impact of this extraordinary status on the community of Delphi and its surrounding region. In this paper I propose that, as the sanctuary of Delphi came to repre sent order, conciliation, and mediation to the Greeks, the local topography of the region was made to reflect these same themes. Delphi and Mt Parnassus became, through myth and ritual, a landscape in which tensions between wildness and civilization-a polarity at the heart of the culture of the polis could be narrated, enacted, and organized. Delphi and Parnas sus stood for the polarities from which the polis was construc ted. On the one side was Delphi, representing the triumph of order over chaos, as expressed in the myth of the sanctuary's foundation, when Apollo destroys Pytho and brings culture to the original inhabitants of Parnassus (Strab. 9.3.12). On the other side was Mt Parnassus, the wilderness tamed by Apollo. These 1 F. de Polignac, UMediation, Competition, and Sovereignty: The Evolution of Rural Sanctuaries in Geometric Greece,» in S. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

Classified List of Daffodil Names, 1916

noym Horticultural Society. CLASSIFIED List of DAFFODIL NAMES, 1916. Price Is. R.H.S. OFFICES, STOkAGE ntM s.w, PROCESS I NG-ONE Lpl-D17A U.B.C. LIBRARY THE LIBRARY THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA U ' CAT. NO. AE>4.^i>- Nz H$ I Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2010 with funding from University of Britisli Columbia Library http://www.archive.org/details/classifiedlistofOOroya CLASSIFICATION OF DAFFODILS FOR USE AT ALL EXHIBITIONS OF The Royal Horticultural Society. [/if order of llic Coii>ii//.\ [n;,0.\ The enormous increase of late \cars in the number of named Daffodils and the crossing and inter-crossing of the (_)nce fairl\- distinct classes of iiiiigiii- lucdio- -Mu] parvi-coronati into \\hich the \arieties ha\e hitherto been di\'ided have made it imperativeK^ necessary to adopt some ne\v or modified Classifi- cation for Garden and Show purposes. In the Sjiring of igo8, the Council of the Royal Piorticultural Society appointed a Committee to consider the subject, and as a result of its labours all known Daffodils were divided into Seven Classes, and a Classified List was published in the same }ear. This method of Classihcation failed to meet A with general acceptance, and numerous modifications were suggested, conse- quently the Council reappointed the Committee, in 1909, to further consider the matter, with the result that the system of Classification now put forward by the authority' of the Royal Horti- cultural Society was arranged. In 1915 the Leedsii Class (R^) was sub-divided to bring it into line with the Incom- parabilis and Barrii Classes. -

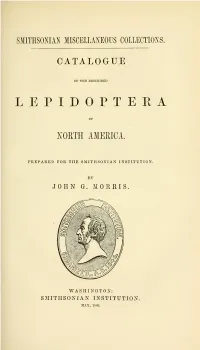

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS. CATALOGUE OF THE DESCRIBED LEPIDOPTERA AT 0RTH AMERICA. PREPARED FOR THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. BY JOHN G. MORRIS WASHINGTON: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. MAY, I860. ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION OCTOBER 1, 1859. Joseph Henry, Secretary S. I. PREFACE. In the preparation of this Catalogue all accessible books have been consulted, and it is believed that no descriptions of American Lepidoptera have been overlooked. The works which ray own library and those of the Smithsonian Institution and the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia do not contain, were kindly lent by entomological friends. The "authorities," enumerated on a subsequent page, will show the extent of my researches. The classification adopted is that recommended in part by Her- rick-Schaeffer and Walker, but in some of the families of the Noc- tuidae I have followed Guenee. A catalogue like the present is not the place for strict scientific classification ; that must be left for a systematic descriptive work. As far as p. 49, Guenee's volumes have been cited according to their number as regards the subject, ex. gr. vol. Y. of the Suites d Buffon, is vol I. of Noctuelites, and I have thus referred to them, but after p. 49 they are quoted according to the Suites. I am well aware of the imperfections of this Catalogue in many respects, but it will still give a fair exhibition of what has been accomplished in this department. The Mexican and West Indian species have been included, or most of them, at the earnest entreaty of several entomologists; firstly, because some of the species are common to the continent and the islands; and, secondly, because it is not impossible that before many years our political boundaries may extend over some of those countries. -

Altes Und Neues Über Zygaena Corycia Stgr. , Z. Graslini

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Internationale Entomologische Zeitschrift Jahr/Year: 1932 Band/Volume: 26 Autor(en)/Author(s): Reiß Hugo Artikel/Article: Altes und Neues über Zygaena corycia Stgr., Z. graslini Led., Z. cambysea Led. und Z. cuvieri Boisd. (Lep.). 269-280 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at 269 — Internationale Entomologische Zeitschrift Organ des Internationalen Entotnologen-Bundes und des Reichsverbandes Deutscher Entomologen-Vereine 26. Jahrgang. 1. Oktober 1932. Nr. 25. Inhalt: Reiß: Altes und Neues über Zygaena corycia Stgr.. Z. graslini Led., Z. cambysea Led. und Z. cuvieri Boisd. (Lep.). — Niepelt: Ein neuer Hybrid der Gattung CelerioOk.— Bandermann: Bemeikungen zu dem Aitikel: Biologie von Epizeuxis calvaria F. (Lepid. Noct.) — Heddergott: Arichanna melanaria L. im Ruhrgebiet. — Loibl: Bitte an die Sammler: Wo ist Cymatophora or ab. albingensis Warn, gefunden worden ? Altes und Neues über Zygaena corycia Stgr., Z. graslini Led., Z. cambysea Led. und Z. cuvieri Boisd. (Lep.). Von Hugo Reiß, Stuttgart. Mit 1 Tafel. 1. Zygaena (Mesembrynus) corycia Stgr. Staudinger beschreibt corycia in Horae Societatis Entomo- logieae Rossicae, p. 318, im Jahre 1878 als Rasse von brizae Esp. wie folgt: „Lederer fand diese Art zuerst, wenn ich nicht irre, bei Magnesia („Dschichmam Deressi“ steht unter zwei seiner Stücke), später im Taurus, und versandte unter dem Namen Corycia als fragliche eigene Art. Die Stücke sind etwas kleiner, 23—26 mm, als Brizae, die Vorderflüge] scheinen etwas kürzer, abgerundeter zu sein, die Beschuppung ist dünner und das Roth nicht so lebhaft, matter als bei Brizae Esp. Sonst sehe ich keinen Unterschied von dieser Art, und da drei ebenso kleine und geformte Stücke aus dem Libanon das volle Roth der Brizae haben, so glaube ich um so mehr, daß Corycia nur die kleinasiatische Varietät der Brizae ist. -

JUDGMENT of MIDAS Opera In

Opera in JUDGMENT OF MIDAS Two Acts Kamran Ince with Crawford Greenewalt, Jr. WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1562/63 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2015 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA :: DDD Music by Kamran Ince Libretto by Miriam Seidel WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. Present Music :: Milwaukee Opera Theatre :: Kamran Ince, conductor TRACK LIST Opera in ACT I (CD 1) ACT II (CD 2) JUDGMENT OF MIDAS Two Acts Scene 1: Frannie and Theo Scene 3: The Contest 1 “I bring you Sardis!” [8:31] 1 “Now, let the contest begin!” [2:23] Music by Kamran Ince :: Libretto by Miriam Seidel 2 “He hears my voice but not what 2 “I am the voice inside the reeds” [2:34] I say” [3:46] 3 “Help me cheer him on” [4:57] 3 “There were grand mosaics depicting 4 “I bring to all the light of reason” [3:35] Matthew DiBattista, tenor (Melik/Midas) :: Abigail Fischer, mezzo-soprano (Frannie) Gods and man” [1:09] 5 “I never heard such sounds before” [1:14] :: Gregory Gerbrandt, baritone (Theo) Jennifer Goltz, coloratura soprano (Pan) 4 “My music—it is respected but no one 6 “My incense is the sweet hyacinth” [2:12] Mikhail Svetlov, bass (The MounTain god TMolus) :: Phillip Horst, bass baritone (aPollo) loves it” [3:12] 7 “I call the truth from every soul” [4:46] 5 “Not for one day?” [2:06] 8 “I enter them, I fill them up” [4:16] Present Music :: Kevin Stalheim, artistic director 6 “He stumbled on a contest” [3:10] -

Cephalophobia N O .1 I SSUE 1 S PRING 2014 CEPHALOPHOBIA

Cephalophobia N O .1 I SSUE 1 S PRING 2014 CEPHALOPHOBIA In This Issue... Two Years of Squamous Horror 3 Academic Departments Classics Department 4 Cryptozoology 13 Vocational Education 16 Economics 21 History 27 Modern Languages & Literature 29 Study Abroad 31 The editors of Cephalophobia are particularly grateful to Ian MacLean for the use of his wonderful illustration “Beginnings” featured on the cover of this publication and as design elements throughout. We also wish to acknowledge MUP forum member Wordcraftian, whose suggestion “Cephalophobia” was adopted as the official title of this publication. Cephalophobia is a free publication for the listenership of the Miskatonic University Podcast and other Lovecraft enthusiasts. Supervisory Editor: Keeper Murf Associate Editor and Layout: Professor O.E. Scriven Additional Copyediting: Professor Charles Gerard 2 FOUNDER’S INTRODUCTION Two Years of Squamous Horror Two years since we started. I’d love to say I I’ve also been deeply gratified by the amazing response from knew this crazy idea would last. but the truth is that I had the Call of Cthulhu community. It’s hard to believe that no idea what would come of it. I’ve listened to podcasts our listenership numbered in the single dig- since late 2005, but making one was a whole new world. its when we began two years ago. And while other podcasts may boast larger In many ways, it started with Paul Maclean and numbers at their second anniver- Yog Radio. It was the first podcast I ever lis- sary, I think the MUP community tened to, and Yog-Sothoth.com (YSDC) stands out as one of the most ac- still stands out as a shining example of tive, informative and friendly on- amazing community builiding.