Roads and Trails Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Survey of Wyoming

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WYOMING SELECTED REFERENCES USED TO CO~IPILE THE ~IETALLIC AND INDUSTRIAL MI ERALS ~IAP OF WYOMING by Ray E. Harris and W. Dan Hausel OPEN FILE REPORT 85-1 1985 This report has no~ been reviewed for conformity with the editorial standards of the Geological Survey of Wyoming. CONTENTS District or Region Page Introduction . iii Absaroka Mountains ...........................•.......................... 1 Aladdin District . 1 Barlow Canyon District . 1 Bear Lodge District . 1 Big Creek District . 2 Bighorn Basin . 2 Bighorn Mountains ...•................................................... 3 Black Hills . 4 Carlile District ...........•............................................ 5 Centennial Ridge District . 5 Clay Spur District ...................................•.................. 5 Colony District . 6 Cooke City - New World District . 6 Copper Mountain District .........................................•...... 7 Cooper Hill District . 7 Crooks Gap-Green Mountain District . 7 Deer Creek District . 8 Denver Basin . 8 Elkhorn Creek District . 8 Esterbrook District . 8 Gas Hills District . 8 Gold Hill District . 9 Grand Encampment District . 9 Granite Mountains . 9 Green River Basin ................................•...................... 10 Gras Ventre Mountains ..................•...............•................ 11 Hanna Basin . 11 Hartville Uplift . 12 Hulett Creek District .........................................•......... 13 Iron Mountain District . 13 Iron Mountain Kimberlite District ......•............................... -

Nonforested Terrestrial Ecosystems Report

Assessment Forest Plan Revision Final Nonforested Terrestrial Ecosystems Report Prepared by: Kim Reid Rangeland Management Specialist for: Custer Gallatin National Forest February 16, 2017 1 Custer Gallatin National Forest Assessment – Nonforested Terrestrial Ecosystems Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Process, Methods and Existing Information Sources .................................................................................... 2 Scale .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Current Forest Plan Direction ....................................................................................................................... 4 Custer Forest Plan ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Gallatin Forest Plan ................................................................................................................................... 7 Existing Condition ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Key Ecosystem Components ..................................................................................................................... 7 Structure and Composition .................................................................................................................. -

Geologic Map of the Sedan Quadrangle, Gallatin And

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC INVESTIGATIONS SERIES I–2634 Version 2.1 A 25 20 35 35 80 rocks generally fall in the range of 3.2–2.7 Ga. (James and Hedge, 1980; Mueller and others, 1985; Mogk and Henry, Pierce, K.L., and Morgan, L.A., 1992, The track of the Yellowstone hot spot—Volcanism, faulting, and uplift, in Link, 30 5 25 CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS 10 30 Kbc Billman Creek Formation—Grayish-red, grayish-green and gray, volcaniclastic mudstone and siltstone ၤ Phosphoria and Quadrant Formations; Amsden, Snowcrest Range and Madison Groups; and Three Overturned 45 20 10 30 20 P r 1988; Wooden and others, 1988; Mogk and others, 1992), although zircons have been dated as old as 3.96 Ga from P.K., Kuntz, M.A., and Platt, L.B., eds., Regional geology of eastern Idaho and western Wyoming: Geological 40 Ksms 45 Kh interbedded with minor volcanic sandstone and conglomerate and vitric tuff. Unit is chiefly 30 30 25 45 45 Forks Formation, Jefferson Dolomite, Maywood Formation, Snowy Range Formation, Pilgrim Ksl 5 15 50 SURFICIAL DEPOSITS quartzites in the Beartooth Mountains (Mueller and others, 1992). The metamorphic fabric of these basement rocks has Society of America Memoir 179, p. 1–53. 15 20 15 Kbc volcaniclastic mudstone and siltstone that are gray and green in lower 213 m and grayish red above; Estimated 40 Qc 5 15 Qoa Limestone, Park Shale, Meagher Limestone, Wolsey Shale, and Flathead Sandstone, undivided in some cases exerted a strong control on the geometry of subsequent Proterozoic and Phanerozoic structures, Piombino, Joseph, 1979, Depositional environments and petrology of the Fort Union Formation near Livingston, 15 25 Ksa 50 calcareous, containing common carbonaceous material and common yellowish-brown-weathering 60 40 20 15 15 (Permian, Pennsylvanian, Mississippian, Devonian, Ordovician, and Cambrian)—Limestone, Ksa 20 10 10 45 particularly Laramide folds (Miller and Lageson, 1993). -

Inactive Mines on Gallatin National Forest-Administered Land

Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Gallatin National Forest-AdministeredLand Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology Abandoned-Inactive Mines Program Open-File Report MBMG 418 Phyllis A. Hargrave Michael D. Kerschen CatherineMcDonald JohnJ. Metesh PeterM. Norbeck RobertWintergerst Preparedfor the u.s. Departmentof Agriculture ForestService-Region 1 Abandoned-Inactive Mines on Gallatin National Forest-AdministeredLand Open-File Report 418 MBMG October 2000 Phyllis A. Hargrave Michael D. Kerschen Catherine McDonald John J. Metesh Peter M. Norbeck Robert Wintergerst for the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service-Region I Prepared Contents List of Figures .V List of Tables . VI IntToduction 1 1.IProjectObjectives 1 1.2AbandonedandInactiveMinesDefined 2 1.3 Health and Environmental Problems at Mines. 3 1.3.1 Acid-Mine Drainage 3 1.3.2 Solubilities of SelectedMetals 4 1.3.3 The Use of pH and SC to Identify Problems. 5 1.4Methodology. 6 1.4.1 Data Sources : 6 1.4.2Pre-Field Screening. 6 1.4.3Field Screening. 7 1.4.3.1 Collection of Geologic Samples. 9 1.4.4 Field Methods ' 9 1.4.4.1 Selection of Sample Sites 9 1.4.4.2 Collection of Water and Soil Samples. 10 1.4.4.3 Marking and Labeling Sample Sites. 10 1.4.4.4ExistingData 11 1.4.5 Analytical Methods """"""""""""""""'" 11 1.4.6Standards. 12 1.4.6.1Soil Standards. 12 1.4.6.2Water-QualityStandards 13 1.4.7 Analytical Results 13 1.5 Gallatin National Forest 14 1.5.1 History of Mining 16 1.5.1.1 Production 17 1.5.1.2Milling 18 1.6SummaryoftheGallatinNationaIForestInvestigat~on 19 1.7 Mining Districts and Drainages 20 Gallatin National Forest Drainages 20 2.1 Geology "' ' '..' ,.""...' ""." 20 2.2 EconomicGeology. -

Proposed Action–Revised Forest Plan, Custer Gallatin National Forest

United States Department of Agriculture Proposed Action–Revised Forest Plan, Custer Gallatin National Forest Forest Service January 2018 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (for example, Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Geographic Areas in the Snowy Range Mountains

Chapter 3 MEDICINE BOW NATIONAL FOREST Revised Land and Resource Management Plan Geographic Areas Table of Contents 3.................................................................................................................................... 3-1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................3-1 Relationship to Forest Plan Direction.....................................................................3-1 Desired Condition...................................................................................................3-1 Purpose of Geographic Areas .................................................................................3-1 Description of Geographic Areas............................................................................3-2 GEOGRAPHIC AREAS IN THE LARAMIE RANGE ...........................................................3-4 Bear Creek Geographic Area..................................................................................3-5 Box Elder Geographic Area....................................................................................3-8 Cottonwood Creek Geographic Area....................................................................3-11 Horseshoe Creek Geographic Area.......................................................................3-14 LaBonte Creek Geographic Area..........................................................................3-17 Palmer Canyon Geographic Area .........................................................................3-20 -

The Undergraduate Scholars Program Acknowledges the Following Sponsors and Partners for Their Ongoing Support of Student Research

The Undergraduate Scholars Program Acknowledges the Following Sponsors and Partners for their Ongoing Support of Student Research: American Indian Research Opportunities (AIRO) Center for Biofilm Engineering McNair Scholars Program Montana INBRE Program Montana Space Grant Consortium College of Agriculture College of Arts & Architecture College of Business College of Education, Health & Human Development College of Engineering College of Letters & Science College of Nursing Honors College Office of the Provost The Graduate School Vice President for Research & Economic Development 1 Table of Contents Map ............................................................................................................................ 3 Topical Sessions .................................................................................................. 4 McNair Scholars ................................................................................................................................4 Plant Science & Agricultural Research .....................................................................................5 Morning Poster Presentations ......................................................................... 6 Afternoon Poster Presentations...................................................................... 18 Graduate Abstracts College of Agriculture........................................................................................................................ 31 College of Arts & Architecture....................................................................................................... -

Surrounded by Mountains

Surrounded by Mountains he Gallatin Valley is one of the most picturesque and Rockies into the jagged peaks we see today. Over the last 50 Geo-Facts: agriculturally productive valleys in Montana. From million years, western Montana experienced several phases of • From the summit of Sacagawea Peak (9,596 ft.) in the northern here, you can see four prominent Montana mountain regional extension and block-faulting, resulting in the creation Bridger Range, you can see even more ranges in a spectacular Tranges: the Bridger Range (east), Gallatin Range (south), of modern Basin-and-Range topography. The crest of the 360o panorama of southwest Montana. Spanish Peaks (southwest), and the Big Belt Mountains Bridger Range arch slowly down-dropped one earthquake at a • A pluton is an intrusive igneous rock body that crystallized from (north). Each range has its own unique geology and topography. time to form the modern Gallatin Valley. Thick layers of mid- magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Its name The high peaks of the Gallatin Range are carved from volcanic and late Cenozoic sedimentary rocks and more recent stream comes from Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld. rocks and volcanic-derived mudflows that erupted during the deposits have been deposited in the Gallatin Valley, producing • One of the richest gold strikes in Montana history was made at Eocene, approximately 45 million years ago. The Spanish Peaks the fertile landscape that Native Americans called the “Valley of Confederate Gulch in the Big Belt Mountains in 1864. Miners expose metamorphic rocks that date back to the Earth’s early Flowers” – the Gallatin Valley. -

Peak Bagging

Peak Bagging: (complete award size: 8" x 6") Program and Awards Offered by the HIGH ADVENTURE TEAM Greater Los Angeles Area Council Boy Scouts of America The High Adventure Team of the Greater Los Angeles Area Council-Boy Scouts of America is a volunteer group of Scouters which operates under the direction of GLAAC-Camping Services. Its mission is to develop and promote outdoor activities within the Council and by its many Units. It conducts training programs, sponsors High Adventure awards, publishes specialized literature such as Hike Aids and The Trail Head and promotes participation in summer camp, in High Adventure activities such as backpacking, peak climbing, and conservation, and in other Council programs. Anyone who is interested in the GLAAC-HAT and its many activities is encouraged to direct an inquiry to the GLAAC-Camping Services or visit our web site at http://www.glaac-hat.org/. The GLAAC-HAT meets on the evening of the first Tuesday of each month at 7:30 pm in the Cushman Watt Scout Center, 2333 Scout Way, Los Angeles, CA 90026. These meetings are open to all Scouters. REVISIONS Jan 2016 General revision. Peak Bagger Peak list: Tom Thorpe removed Mt. San Antonio, added Blackrock Dick Rose Mountain. Mini-Peak Bagger list: removed Dawson Peak and Pine Mountain No. 1. Renamed "Suicide Peak" to "Suicide Rock". Updated "General Requirements" section. Jan 2005 New document incorporating Program Announcements 2 and 3. Prepared by Lyle Whited and composed by John Hainey. (Mt. Markham, summit trail) Peak Bagging Program and Awards -

Assessment Report Was Created to Summarize 25 Individual Specialist Reports

Assessment – Introduction and Public and Tribal Involvement Assessment Forest Plan Revision Draft Introduction and Public and Tribal Involvement Report Prepared by: Virginia Kelly, Forest Plan Revision Team Leader Mariah Leuschen-Lonergan, Forest Plan Revision Public Affairs for: Custer Gallatin National Forest November 29, 2016 Assessment – Introduction and Public and Tribal Involvement Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Location of the Custer Gallatin National Forest ........................................................................................ 1 About the Assessment .................................................................................................................................. 2 Assessment Structure ............................................................................................................................... 3 Best Available Scientific Information in the Assessment .......................................................................... 3 Landscape Areas ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Madison, Henrys Lake, Gallatin, Absaroka and Beartooth Mountains ................................................. 4 Bangtail, Bridger, and Crazy Mountains ............................................................................................... 5 Pryor Mountains -

Interpreting the Timberline: an Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1966 Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America Stephen Arno The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arno, Stephen, "Interpreting the timberline: An aid to help park naturalists to acquaint visitors with the subalpine-alpine ecotone of western North America" (1966). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6617. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6617 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTEKFRETING THE TIMBERLINE: An Aid to Help Park Naturalists to Acquaint Visitors with the Subalpine-Alpine Ecotone of Western North America By Stephen F. Arno B. S. in Forest Management, Washington State University, 196$ Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Forestry UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1966 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners bean. Graduate School Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP37418 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

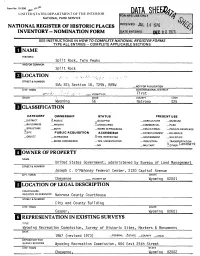

CLASSIFI C ATI ON

Form No. 10-300 \$&-, \Q^ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MA NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY--NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS [NAME HISTORIC Split Rock, Twin Peaks AND/OR COMMON Split Rock ^ SE% Section 18, T29N, R89W —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT W^:- -; f -£ H.- ' -C __ VICINITY OF First STATE v CODE COUNTY CODE Wyoming 56 Natrona 025 CLASSIFI c ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT 2LPUBLIC -OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE IlUNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —X.SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x^OTHER:TUCD. Landmark OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME United States Government; administered by Bureau of Land Management STREET & NUMBER Joseph C. O'Mahoney Federal Center, 2120 Capitol Avenue CITY, TOWN STATE Cheyenne _ VICINITY OF Wyoming 82001 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF c. Natrona County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER City and County Building CITY. TOWN STATE Casper, Wyoming 82601 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Wyoming Recreation Commission, Survey of Historic Sites, Markers & Monuments DATE' 1967 (revised 1973) —FEDERAL J^STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Wyoming Recreation Commission, 604 East 25th Street CITY, TOWN STATE Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED ^UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE __GOOD _RUINS —ALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ _FAIR ^.UNEXPOSED ———————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE In central Wyoming the Sweetwater River Valley and flanking mountains to the north called the Granite Range were formed by geologic forces over a long period of time.