Detailed Species Accounts from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the Flagship Species of North-East Asia

North-East Asian Subregional Programme for Environmental Cooperation (NEASPEC) SAVING THE FLAGSHIP SPECIES THE FLAGSHIP SAVING SAVING THE FLAGSHIP SPECIES OF NORTH-EAST ASIA OF NORTH-EAST ASIA United Nations ESCAP United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Environment and Sustainable Development Division United Nations Building Rajadamnern Nok Avenue Nature Conservation Strategy of NEASPEC Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel: (662) 288-1234; Fax: (662) 288-1025 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: <http://www.unescap.org/esd> United Nations ESCAP ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC ESCAP is the regional development arm of the United Nations and serves as the main economic and social development centre for the United Nations in Asia and the Pacific. Its mandate is to foster cooperation between its 53 members and 9 associate members. ESCAP provides the strategic link between global and country-level programmes and issues. It supports the Governments of the region in consolidating regional positions and advocates regional approaches to meeting the region’s unique socio-economic challenges in a globalizing world. The ESCAP office is located in Bangkok, Thailand. Please visit our website at www.unescap.org for further information. Saving the Flagship Species The grey shaded area of the map represents the members and associate members of ESCAP of North-East Asia: United Nations publication Nature Conservation Strategy of NEASPEC Copyright© United Nations 2007 ST/ESCAP/2495 -

Dmz Full Day Tour

DMZ TOUR DMZ FULL DAY TOUR 08:30 ~ 17:00 (Lunch Included) US$67 Imjingak Pavilion → The Unification Bridge → ID Check → DMZ → Film Presentation → Exhibition Hall → The 3rd Infiltration Tunnel → Dora Observatory → Dorasan Station → Pass by Unification Village → Paju Shopping Outlet DMZ: Korea is the only divided country in the world. After the Korean War (June 25 1950 – July 27 1953), South Korea and North Korea established a border that cut the Korean peninsula roughly in half. Stretching for 2km on either side of this border is the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Imjingak pavilion –The Unification Bridge – ID Check –DMZ –Film presentation -& Exhibition-Hall –The 3rdinfiltration tunnel – Dora observatory –Dorasan station –Pass by unification. It is strongly advised the attire should be casual with comfortable walking shoes as you will be walking inside tunnel. The guided tour will be followed with no one left astray as we move through the 3rd infiltration tunnel. (Every Monday – N/A) Paju Premium Outlets, Korea’s second Premium Outlet Center, is a one-hour drive from Seoul featuring 160 designer and name brand outlet stores at savings of 25% to 65% every day in an upscale, outdoor setting. (Some items may be excluded.) In addition to 160 stores, Paju Premium Outlets accommodates a food court with 600 seats and 20 restaurants & cafe to enhance the shopping enjoyment. Concierge service, stroller and wheelchair rentals and tour information are provided at the Information Center. Only 44 km (27 miles) from Seoul, the tunnel was discovered in October -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Tracing Population Movements in Ancient East Asia Through the Linguistics and Archaeology of Textile Production

Evolutionary Human Sciences (2020), 2, e5, page 1 of 20 doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.4 REVIEW Tracing population movements in ancient East Asia through the linguistics and archaeology of textile production Sarah Nelson1, Irina Zhushchikhovskaya2, Tao Li3,4, Mark Hudson3 and Martine Robbeets3* 1Department of Anthropology, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2Laboratory of Medieval Archaeology, Institute of History, Archaeology and Ethnography of Peoples of Far East, Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, Russia, 3Eurasia3angle Research group, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, Jena, Germany and 4Department of Archaeology, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Archaeolinguistics, a field which combines language reconstruction and archaeology as a source of infor- mation on human prehistory, has much to offer to deepen our understanding of the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Northeast Asia. So far, integrated comparative analyses of words and tools for textile production are completely lacking for the Northeast Asian Neolithic and Bronze Age. To remedy this situation, here we integrate linguistic and archaeological evidence of textile production, with the aim of shedding light on ancient population movements in Northeast China, the Russian Far East, Korea and Japan. We show that the transition to more sophisticated textile technology in these regions can be associated not only with the adoption of millet agriculture but also with the spread of the languages of the so-called ‘Transeurasian’ family. In this way, our research provides indirect support for the Language/Farming Dispersal Hypothesis, which posits that language expansion from the Neolithic onwards was often associated with agricultural colonization. -

Whose War Is the Korean War? AUTHOR INFORMATION Author

WHDE Lesson Plan Whose war is the Korean War? AUTHOR INFORMATION Author: Matthew Britton State: Florida GENERAL INFORMATION Lesson Grade Span: Secondary (9-12) Targeted Grade Level/Course: 9th -12th Estimated Time to Complete Lesson: 135 – 180 min FOCUSED QUESTION Why is the Korean War still happening? STANDARDS (STATE/C3) SS.912.W.9.2 Describe the causes and effects of post-World War II economic and demographic changes. SS.912.W.8.3 Summarize key developments in post-war China. SS.912.W.8.4 Summarize the causes and effects of the arms race and proxy wars in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. SS.912.W.9.4 Describe the causes and effects of twentieth century nationalist conflicts. STUDENT & TARGET OUTCOMES SWBAT: Understand the difference between Communism and Capitalism and how these ideas impacted countries throughout the world. Describe the reasoning for involvement from so-called “first world” nations in affairs outside their borders. Understand the reasoning behind anti-imperialist nations, when creating governments in opposition to imperialist governments. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED WHDE WHDE Lesson Plan LESSON OVERVIEW The main focus of this lesson is to illustrate why each party (South Korea, North Korea, US and China) are engaged in what has become a perpetual war of the Koreas. The lesson attempts to show that each nation has really no reason to end a “war” that for the most part is “bluster.” PROCEDURES Step by Step Instructions for Educators: Plan of Instruction: Note: Student should be familiar with the Korean War, Imperialism and WWII from the Japanese Imperialist perspective. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

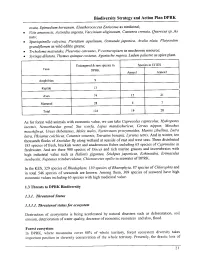

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

Environmental Evolution of Xingkai (Khanka) Lake Since 200 Ka by OSL Dating of Sand Hills

Article Geology August 2011 Vol.56 No.24: 26042612 doi: 10.1007/s11434-011-4593-x SPECIAL TOPICS: Environmental evolution of Xingkai (Khanka) Lake since 200 ka by OSL dating of sand hills ZHU Yun1,2, SHEN Ji1*, LEI GuoLiang2 & WANG Yong1 1 Key Laboratory of Lake Science and Environment, Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; 2 College of Geographical Sciences, Fujian Normal University, Fujian Key Laboratory of Subtropical Resources and Environment, Fuzhou 350007, China Received February 28, 2011; accepted May 13, 2011 Crossing the Sino-Russian boundary, Xingkai Lake is the largest freshwater lake in Northeast Asia. In addition to the lakeshore, there are four sand hills on the north side of the lake that accumulated during a period of sustainable and stable lacustrine trans- gression and were preserved after depression. Analysis of well-dated stratigraphic sequences based on 18 OSL datings combined with multiple index analysis of six sites in the sand hills revealed that the north shoreline of Xingkai Lake retreated in a stepwise fashion since the middle Pleistocene, and that at least four transgressions (during 193–183 ka, 136–130 ka, 24–15 ka and since 3 ka) and three depressions occurred during this process. The results of this study confirmed that transgressive stages were concur- rent with epochs of climate cooling, whereas the period of regression corresponded to the climatic optima. Transgressions and regressions were primarily caused by variations in the intensity of alluvial accumulation in the Ussuri River Valley and fluctua- tions in regional temperature and humidity that were controlled by climatic change. -

Print This Article

97 Flyway structure, breeding, migration and wintering distributions of the globally threatened Swan Goose Anser cygnoides in East Asia IDERBAT DAMBA1,2,3, LEI FANG1,4, KUNPENG YI1, JUNJIAN ZHANG1,2, NYAMBAYAR BATBAYAR5, JIANYING YOU6, OUN-KYONG MOON7, SEON-DEOK JIN8, BO FENG LIU9, GUANHUA LIU10, WENBIN XU11, BINHUA HU12, SONGTAO LIU13, JINYOUNG PARK14, HWAJUNG KIM14, KAZUO KOYAMA15, TSEVEENMYADAG NATSAGDORJ5, BATMUNKH DAVAASUREN5, HANSOO LEE16, OLEG GOROSHKO17,18, QIN ZHU1,4, LUYUAN GE19, LEI CAO1,2 & ANTHONY D. FOX20 1State Key Laboratory of Urban and Regional Ecology, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100085, China. 2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China. 3Ornithology Laboratory, Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. 4Life Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China. 5Wildlife Science and Conservation Center of Mongolia, Union Building B701, Ulaanbaatar 14210, Mongolia. 6Planning and Design Team of Datian Forestry Investigation, Fujian 366100, China. 7Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency, Gimcheon 39660, Korea. 8National Institute of Ecology, Seocheon 33657, Korea. 9Fujian Wildlife Conservation Center, Fuzhou 350003, China. 10Jiangxi Poyang Lake National Reserve Authority, Nanchang, Jiangxi 330038, China. 11Shengjin Lake National Nature Reserve, Dongzhi, Anhui, China. 12Nanji Wetland National Nature Reserve Agency, Nanchang, China. 13Inner Mongolia Hulun Lake National Nature Reserve Administration, Hulunbeir 021008, China. 14Migratory Bird Research Center National Institute of Biological Research, Incheon, Korea. 15Japan Bird Research Association, Tokyo, Japan. 16Korea Institute of Environmental Ecology, 62-12 Techno 1-ro, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon 34014, Korea. 17Daursky State Nature Biosphere Reserve, Zabaykalsky Krai, 674480, Russia. 18Chita Institute of Nature Resources, Ecology and Cryology, Zabaykalsky Krai 672014, Russia. -

Appendix 6.2: Responses to Transboundary Environmental Challenges Within the Europe and Central Asia Region (Chapter 6, Section 6.3.3)

IPBES Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Appendix 6.2 for Europe and Central Asia Appendix 6.2: Responses to transboundary environmental challenges within the Europe and Central Asia region (Chapter 6, Section 6.3.3) Table 6.2.1 shows a number of bilateral agreements between Mongolia, Russia and China related to water management and nature conservation relevant to transboundary Amur River basin. Table 6.2.1: Bilateral water and nature conservation agreements between Mongolia, Russia and China Title Description Sino-Soviet Agreement on Agreement between the USSR and China on joint research operations on 1956 development of “Grand planning and survey operations to prepare a scheme for the multi- Amur Scheme” purpose exploitation of the Argun River and the Upper Amur River. Sino-Russian Agreement Bilateral overview of developments planned by the water and energy 1986 on development of “Joint authorities of China and Russia led by the Song-Liao Water Resource Comprehensive Scheme Commission of China and Sovintervod Hydro-engineering Institute of for Water Management on USSR Water Resources Ministry. Amur and Argun Rivers” Mongolia-China – 1994 Agreement on Use and Agreement on the protection and utilization of transboundary waters Protection of including aquatic biota Transboundary Waters Russia-China Agreement Protects 25 fishes, two crustaceans, one turtle, one mollusk, three 1994 on protection of aquatic aquatic plants. Regulates size limits for fish, net mesh sizes and lengths, bio-resources in seasonal fishing bans, closure of waters to fishing, and permitted fishing transboundary Amur- and gear. Does not cover Argun river and Khanka Lake. Ussuri Rivers Agreement on Dauria Trilateral agreement was signed by China, Mongolia, and Russia to 1994 International Protected establish Dauria International Protected Area (DIPA) to protect globally Area important grasslands in the headwaters of the Amur-Heilong basin. -

DRAINAGE BASINS of the SEA of OKHOTSK and SEA of JAPAN Chapter 2

60 DRAINAGE BASINS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN Chapter 2 SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN 61 62 AMUR RIVER BASIN 66 LAKE XINGKAI/KHANKA 66 TUMEN RIVER BASIN Chapter 2 62 SEA OF OKHOTSK AND SEA OF JAPAN This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan and their major transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basins of these seas. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASINS OF THE SEA OF OKHOTSK AND THE SEA OF JAPAN1 Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km2) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Amur 1,855,000 Sea of Okhotsk CN, MN, RU … - Argun 164,000 Amur CN, RU … - Ussuri 193,000 Amur CN, RU Lake Khanka Sujfun 18,300 Sea of Japan CN, RU … Tumen 33,800 Sea of Japan CN, KP, RU … 1 The assessment of water bodies in italics was not included in the present publication. 1 AMUR RIVER BASIN o 55 110o 120o 130o 140o SEA OF Zeya OKHOTSK R U S S I A N Reservoir F E mur D un A E mg Z A e R Ulan Ude Chita y ilka a A a Sh r od T u Ing m n A u I Onon g ya r re A Bu O n e N N Khabarovsk Ulaanbaatar Qiqihar i MONGOLIA a r u u gh s n s o U CHIN A S Lake Khanka N Harbin 45o Sapporo A Suj fu Jilin n Changchun SEA O F P n e JA PA N m Vladivostok A Tu Kilometres Shenyang 0 200 400 600 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map Ch’ongjin J do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Multi-Destination Tourism in Greater Tumen Region

MULTI-DESTINATION TOURISM IN GREATER TUMEN REGION RESEARCH REPORT 2013 MULTI-DESTINATION TOURISM IN GREATER TUMEN REGION RESEARCH REPORT 2013 Greater Tumen Initiative Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH GTI Secretariat Regional Economic Cooperation and Integration in Asia (RCI) Tayuan Diplomatic Compound 1-1-142 Tayuan Diplomatic Office Bldg 1-14-1 No. 1 Xindong Lu, Chaoyang District No. 14 Liangmahe Nanlu, Chaoyang District Beijing, 100600, China Beijing, 100600, China www.tumenprogramme.org www.economicreform.cn Tel: +86-10-6532-5543 Tel: + 86-10-8532-5394 Fax: +86-10-6532-6465 Fax: +86-10-8532-5774 [email protected] [email protected] © 2013 by Greater Tumen Initiative The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Greater Tumen Initiative (GTI) or members of its Consultative Commission and Tourism Board or the governments they represent. GTI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, GTI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. “Multi-Destination Tourism in the Greater Tumen Region” is the report on respective research within the GTI Multi-Destination Tourism Project funded by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. The report was prepared by Mr. James MacGregor, sustainable tourism consultant (ecoplan.net). -

The Dmz Tour Course Guidebook

THE DMZ TOUR COURSE GUIDEBOOK From the DMZ to the PLZ (Peace and Life Zone) According to the Korean Armistice Agreement of 1953, the cease-fire line was established from the mouth of Imjingang River in the west to Goseong, Gangwon-do in the east. The DMZ refers to a demilitarized zone where no military army or weaponry is permitted, 2km away from the truce line on each side of the border. • Establishment of the demilitarized zone along the 248km-long (on land) and 200km-long (in the west sea) ceasefire line • In terms of land area, it accounts for 0.5% (907km2) of the total land area of the Korean Peninsula The PLZ refers to the border area including the DMZ. Yeoncheon- gun (Gyeonggi-do), Paju-si, Gimpo-si, Ongjin-gun and Ganghwa-gun (Incheon-si), Cheorwon-gun (Gangwon-do), Hwacheon-gun, Yanggu- gun, Inje-gun and Goseong-gun all belong to the PLZ. It is expected that tourist attractions, preservation of the ecosystem and national unification will be realized here in the PLZ under the theme of “Peace and Life.” The Road to Peace and Life THE DMZ TOUR COURSE GUIDEBOOK The DMZ Tour Course Section 7 Section 6 Section 5 Section 4 Section 3 Section 2 Section 1 DMZ DMZ DMZ Goseong Civilian Controlled Line Civilian Controlled Line Cheorwon DMZ Yanggu Yeoncheon Hwacheon Inje Civilian Controlled Line Paju DMZ Ganghwa Gimpo Prologue 06 Section 1 A trail from the East Sea to the mountain peak in the west 12 Goseong•Inje 100km Goseong Unification Observatory → Hwajinpo Lake → Jinburyeong Peak → Hyangrobong Peak → Manhae Village → Peace & Life Hill Section 2 A place where traces of war and present-day life coexist 24 Yanggu 60km War Memoria → The 4th Infiltration Tunnel → Eulji Observatory → Mt.