The Case of Foreign Workers in the French Automobile Assemble Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Van Dimensions

Van Dimensions Roof Height Vehicle Manufacture Vehicle Model Model Year Wheelbase Roof Height Rear Door Wheelbase (mm) (mm) Overall Length (mm) Citroen Berlingo First 1996 - 2009 L1 H1 Twin 2693 1796 4137 Citroen Berlingo 2008 - 2018 L1 H1 Twin 2728 1810 4380 Citroen Berlingo 2008 - 2019 L2 H1 Twin 2728 1810 4628 Citroen Berlingo 2008 - 2020 L2 H1 Tailgate 2728 1810 4628 Citroen Berlingo 2018 - Onwards L1 H1 Twin 2800 1850 4300 Citroen Berlingo 2018 - Onwards L2 H1 Twin 3000 1850 4700 Citroen Jumper 1994 - 2006 L1 H1 Twin 2850 2100 4963 Citroen Jumper 1994 - 2006 L1 H2 Twin 2850 2420 4963 Citroen Jumper 1994 - 2006 L2 H1 Twin 3200 2100 5413 Citroen Jumper 1994 - 2006 L2 H2 Twin 3200 2420 5413 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L1 H1 Twin 3000 2254 4963 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L2 H1 Twin 3450 2254 5413 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L2 H2 Twin 3450 2524 5413 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L3 H2 Twin 4035 2524 5998 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L3 H3 Twin 4035 2764 6363 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L4 H2 Twin 4035 2524 6363 Citroen Jumper 2006 - Onwards L4 H3 Twin 4035 2764 6363 Citroen Jumpy 1995 - 2007 L1 H1 Twin 3000 1980 4805 Citroen Jumpy 1995 - 2007 L2 H1 Twin 3122 1980 5135 Citroen Jumpy 1995 - 2007 L2 H1 Twin 3122 2276 5135 Citroen Jumpy 1995 - 2007 L1 H1 Tailgate 3000 1980 4805 Citroen Jumpy 1995 - 2007 L2 H1 Tailgate 3122 1980 5135 Citroen Jumpy 2008 - 2016 L1 H1 Twin 3000 1980 4805 Citroen Jumpy 2008 - 2016 L1 H1 Tailgate 3000 1980 4805 Citroen Jumpy 2008 - 2016 L2 H1 Twin 3122 1980 5135 Citroen Jumpy 2008 - 2016 L2 H1 Tailgate -

Fos Who's Driving What 27 May 2009 6

Attendance Name Biography Driving/Riding Friday Saturday Sunday Aaltonen, Rauno Monte Carlo and RAC Rally winner, and European Rally Champion Yes Yes Yes Will drive a Mini Cooper S on the Forest Rally Stage Attwood, Richard 1970 Le Mans winner and works BRM, Cooper and Lotus Formula 1 driver Yes Yes Yes Expected to drive the 1971 Le Mans winning Porsche 917K Bell, Derek Five-time Le Mans winner, Formula 1 driver & all round endurance legend Yes Yes Yes Will drive a Mirage GR7, Life 190 and Bentley Speed 8 on the hill Biela, Frank Multiple touring car champion and five-time Le Mans winner Expected Expected Expected Will drive an Audi A4 BTCC of the type he drove to the 1996 British Touring Car Championship Blackburn, Holman European Touring Car Championship Capri driver Yes Yes Yes Will drive a Ford Capri MkII 3000 GT on the hill Blomqvist, Stig 1984 World Rally Champion Yes Yes Yes Expected to drive a Ford RS200, Talbot Sunbeam Lotus and Audi S1 on the hill Brabham, David Sports car veteran and former-F1 driver. Son of Sir Jack. Yes Yes Yes Expected to drive a Cooper T51 of the type his father drove to the 1959 World Championship Brookes, Russell Twice British Rally Champion and star of the British rally scene Yes Yes Yes Will drive an Open Manta 400 and a Talbot Sunbeam Lotus Button, Jenson Brawn GP star and current F1 Championship leader No No Yes Expected to be in action on the hill Capello, Rinaldo Sports car ace and multiple Le Mans winner Expected Expected Expected Will drive an Audi R8R on the hill Cassill, Landon Rising NASCAR -

Competing Grand Prix Technologies of the Past

P.1 of 4 Competing Grand Prix technologies of the past In 2014, when the FIA Formula 1 engine of the 3rd Pressure-Charged (TurboCharged) Era will be so closely specified, even down to the diameter of the valve stems, that it seems likely that only company-specific detail drawing standards will produce any differences (“electrickery” apart), it is interesting to recollect some of the great technical duels of the past century of Grand Prix racing. In 1912 at the French Grand Prix, run under Formule Libre, 14.1 litre FIATs battled with 7.6 litre Peugeots having a more advanced specification and they just lost. The Peugeot introduced Double Overhead Camshafts and this became the valve operating mechanism of choice for nearly all subsequent racing engines and now is commonplace in ordinary production cars. Over 1934 – 1939 the front-engined IL8 and V12 Mercedes-Benz and the mid-engined V16 and V12 Auto Union cars, built firstly to the 750 kg empty and then the 3 litre Pressure-Charged (PC) / 4.5 litre Naturally Aspirated (NA) rules, fought tooth-and-nail for supremacy. This was a German internecine rivalry, perhaps sharpened by geography as Swabia (Stuttgart) versus Saxony (Chemnitz). Mercedes, with about twice the expenditure of Auto Union, beat them over the 48 races which they both contested by 27 wins to 17. Alfa Romeo wins (4) added a little spice occasionally. See Picture 1 on P.3. In 1949, in the temporary absence of Alfa Romeo, the rules which applied 1947 – 1951 allowed 1.5 litre PC cars (V12 Ferrari and IL4 Maserati) to compete with 4.5 litre NA (IL6 Lago-Talbot). -

Racing Brake Products

RACING BRAKE PRODUCTS PADS • DISCS • FLUID 1 2 INDEX PAGID Racing Bedding In RACING BRAKE PADS Company 6 44 Quality Racing & Performance Brake Discs 46 8 NEW RBD MULTI-T 47 Racing Brake Pads NEW Racing FOR KARTING 12 Brake Fluid FOR UTV 14 52 Racing Brake Pads Application List Race Cars RACING BRAKE PADS PAGID RSL 55 ENDURANCE RACING BRAKE PADS 16 Application List Caliper PAGID RST RACING BRAKE PADS RALLY, SPRINT AND STOCK CAR RACING BRAKE PADS 22 81 Shape List RACING BRAKE PADS PAGID RS ALLROUND RACING BRAKE PADS 30 89 Compound PAGID RSC Guide RACING BRAKE PADS FOR RACING BRAKE PADS CERAMIC COMPOSITE DISCS 36 145 Technical PAGID RSH RACING BRAKE PADS Information FOR HISTORIC CARS 40 & Tips 154 3 4 5 About PAGID Racing PAGID Racing is the exclusive motor- racing and high performance calipers and also may be fitted as an sport brand of the TMD Performance. upgrade to many standard calipers for high performance cars. As a member of the TMD Friction Group, TMD Performance is the world- In addition, PAGID Racing brake products are fitted as original equip- wide sole distributor of PAGID Racing ment to some of the most prestigious and powerful production cars in products and high performance brake the world including Audi, Bugatti, Ferrari and Porsche. pads for street legal cars. With the facilities in Leverkusen & Essen (Germany) and Troy (USA), The brake products are designed to produce the highest possible TMD Performance is one of only a small number of companies capable performance levels over a wide range of operating conditions, and are of developing and manufacturing brake friction solutions according to available in many different material formulations. -

Questions and Answers for the Centenary of the Brand Price : €6 GRÉGOIRE THONNAT

Who is the founder of Citroën automobiles? What was the first car produced by Citroën? What is the ‘Citroën Central Asia’ Expedition? What do Citroën Traction Avant, Citroën 2 CV, Citroën DS and Citroën Ami 6 have in common? Who invented Citroën Mehari? What is the bestselling car in the Brand’s history? In 80 questions and answers, a timeline and the description of 10 iconic models, this little book will help you (re)discover Citroën’s fabulous history through iconic models, technical innovations and the people who wrote this unique industrial adventure that has revolutionised the history of the automobile since 1919. Questions and answers for the centenary of the Brand Price : €6 GRÉGOIRE THONNAT LE PETIT QUIZZ Questions and answers for the centenary of the Brand GRÉGOIRE THONNAT SUMMARY Preface 5 Questions and answers 7 A brief timeline of Citroën 89 10 iconic vehicles of the Brand 101 The Citroën brand 123 5 Dear readers, There is a reason why the Citroën 2 CV is as much a symbol of France as the Eiffel Tower…because we all have a Citroën story to tell! However, do you know the story of Citroën itself? Le Petit Quiz invites you to (re)discover Citroën’s journey from the origin of its logo to its many technological innovations, from legendary cars to its sporting achievements, and taking a detour through its cult advertising campaigns throughout the years. These 80 questions will help you discover amusing anecdotes and relive Citroën’s history! As the centenary of Citroën approaches, this is the essential tool to ensure you are ‘up to speed’ with one of the most collected car brands in the world… Linda Jackson, CEO, Citroën Brand 5 QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS 7 WHO WAS THE FOUNDER OF CITROËN? André Citroën! Born on 5 February 1878, André graduated from École Polytechnique and then went on to found Engrenages Citroën in 1905, before leading Mors automobiles in 1908. -

New Citroën C5 Aircross Suv

NEW CITROËN C5 AIRCROSS SUV 1 During the 90s Le Tone had a major hit, “Joli Dragon”, and devoted himself to music for 15 years before progressively moving towards illustrative art. Since 2011 his creations have been exhibited in famous places such as the Pompidou centre. An admirer of artists who know how to make the best use of colour, Le Tone confesses to having a weakness for black and white, which he uses to tell simple stories by using felt pen drawings in notebooks. 1974 2016 Citroën launches CX. It’s the ultimate Experience Concept reinvents mix of technical innovation and the prestige saloon. A bold, advanced design with the engine and fresh silhouette, a high-end stylish gearbox positioned together at the interior and the latest technology front. Sophisticated hydropneumatic combine to inspire the world of suspension, concave rear screen and a automotive design. futuristic dashboard help it to succeed amongst more ordinary rivals. 1934 1939 1948 1955 1968 2017 Discover the models that make up Citroën revolutionises the automotive Citroën launches the ‘TUB’, a supremely The much-loved 2CV is created as Unveiled to a stunned public at the 1955 It’s a golden age for light and agile Winners of the Manufacturers’ Rally Raid World Cup from Citroën’s extraordinary history, landscape with the Traction Avant. practical modern design with a sliding side a “safe and economical vehicle, Paris Motor Show, the DS takes futuristic vehicles like the Ami 6, Dyane and 1993 to 1997; Rally Raid World Cup Drivers’ Champion from 1919 to the present day. -

HISTORIC As the “Museum of the Year” MOTORING by the International Historic Motoring Awards

THE It is my pleasure to welcome INTERNATIONAL you to the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum, selected HISTORIC as the “Museum of the Year” MOTORING by the International Historic Motoring Awards. MUSEUM OF THE YEAR To experience The Spirit of Competition come alive, 2011 join us for our bi-monthly Demo Days. Along with running the cars around our 3 acre back lot, I will give PUBLICATION OF THE YEAR a lesson on the specs, history and provenance on 2012 each of the automobiles. Our philosophy is that it is not just the mechanics of the machine, or how fast it can CAR OF THE YEAR go, but about where the car has been and what it has 2014 experienced. Each one has a story worthy of hearing. MUSEUM OF THE YEAR I hope you enjoy this exhibition, find it educational, and 2017 will come back to visit us often. Fred Simeone Voted best car collection in the world by the Classic Car Trust ClassicCarTrust.com CELEBRATING THE SPIRIT OF COMPETITION 2020 EVENT SCHEDULE January 25 - Best of Britain May 30 - The European Rally August 22 - Sir Stirling Moss, The Champion That Wasn’t 2020 DEMO DAYS England at Le Mans Time, Speed, Distance Aston Martin DBR1, Maserati 300S, Jaguar C-Type, AT SIMEONE MUSEUM Bentley 3 liter, MG K3, Aston Martin LM, Jaguar C-Type Jaguar SS100, Talbot-Lago Grand Sport, Austin-Healey 100 Mercedes 300SL, Jaguar D-Type February 8 - Dawn of The American Sports Car June 13 - Le Mans 1959 September 26 - Ford vs Chevy American Underslung, Mercer Raceabout, National Model 40, Simeone’s 24 Minutes of Le Mans! Cobra Daytona, Corvette 427 -

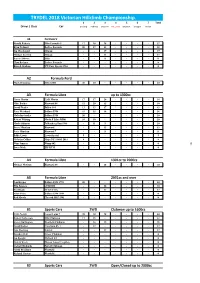

Provisional Results After Round 3.Xlsx

TRYDEL 2018 Victorian Hillclimb Championship. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Total Driver / Class Car Geelong Rob Roy Bryant P. Mt. Leura Bryant P. Shepptn Ararat A1 Formula V Harold Roberts Elfin Formula V 17 20 20 - - - - 57 Ryan Nothard Zedvee Formula 20 17 15 - - - - 52 Ian Macdonald Allman - - 17 - - - - 17 Michael Everton Allman - - 13 - - - - 13 Barry Gibbons Elfin - - 11 - - - - 11 Chas Rechner Zedvee Formula - - - - - - - 0 Russell Graham VW Farr Special 1966 - - - - - - - 0 A2 Formula Ford Mark Brunning Elfin 620B 20 20 - - - - - 40 A3 Formula Libre up to 1300cc Garry Martin GAK Martin 17 17 20 - - - - 54 Mike Barker Hayward 06 15 20 15 - - - - 50 David Pfeiffer Talbot 184 13 13 17 - - - - 43 Peter Weichard Dallara F394 11 15 10 - - - - 36 Malcolm Oastler Dallara F394 20 - - - - - - 20 Robert Whiting Morbi F Libre DR01 10 10 - - - - - 20 Mark Atkinson Falkenberg Jinx 1966 - 11 9 - - - - 20 Bruce Minahan Hayward - - 13 - - - - 13 Peter Minahan Hayward 7 - - 11 - - - - 11 Eddie Lewis Lewis Special 9 - - - - - - 9 Nicholas Collins Ninja NC-1 0001 2014 8 - - - - - - 8 Wim Janssen Wimp 002 - - - - - - - 0 0 Ewen Moile ZIP KTM - - - - - - - 0 A4 Formula Libre 1301cc to 2000cc Michael McGinn Hayward 08 - - 20 - - - - 20 A5 Formula Libre 2001cc and over Jess Harper Dallara F398 1998 20 - - - - - - 20 Win Janssen OMS2000 - - 20 - - - - 20 Fred Galli SYGA-CGA - - 17 - - - - 17 Allan Foley Dallara F398 1998 - - - - - - - 0 Rod Moody Cheetah Mk7 1981 - - - - - - - 0 B1 Sports Cars 2WD Clubman up to 1600cc Colin Newitt Locost Lotus 7 20 20 20 - - - - 60 -

2017 Bfgoodrich Tires 50Th SCORE Baja 1000

2017 BFGoodrich Tires 50th SCORE Baja 1000 Entries Total: 277 10/24/17 7PM PST List Not in Start Order until TDC, Draw & Qualifying Results Apply Qualifying Entry List *Entries listed on Entry List According to Official Policy* Trophy Truck 39 BFGoodrich Tires, RPM Offroad, Rigid Industries, King Shocks, Impact Safety, Luis Montiel, Juan BDS Suspension, KMC Wheels, Par 1 Carlos Apdaly Lopez Q Tecate, BC, MX Carlos Lopez, Geiser Ventures, Inc., Geiser Brothers, Dougans Reynaldo Zavala Engines, Rancho Drivetrain, PIN MFG, BORLA Ed Herbst, Brent Javier's-Finest Foods of Mexico, Ultra 3 Mark Post Q Las Vegas, NV Bauman, Kyle Le Ford Wheels, Baja Design Lighting, Sunset Duc Sign, Toyo Tires BFGoodrich Tires, King Shocks, RPM Doug Fortin, Jeff Offroad, Rigid Industries, Impact Safety, Wykoff, Kellon BDS Suspension, KMC Wheels, Par 4 Justin Matney Q Bristol, VA Walch, Josh Geiser Ventures, Inc., Geiser Brothers, Dougans Daniel, Jake Engines, Rancho Drivetrain, PIN MFG, Johnson BORLA Ricky Johnson, Neal Mason, Steve BFGoodrich Tires, Baja Designs, First 6 Larry Connor Q Lake Elsinore, CA Covey, Ryan Mason TT Billing Services, Mason Motorsports, Arciero, Hudson Mechanix Wear, FK Rod Ends Hall Pete Mortensen, REDBULL, KMC WHEELS,PENNZOIL, 7 Bryce Menzies Q Las Vegas, NV Jake Povey, Jesse Ford BFGoodrich Tires, DISCOUNT TIRE, Baja Jones Designs, Fox Shox, FOCUS Companies RPM Offroad, BFG Tires, Rigid Industries, Bryan Lyttle, King Shocks, Impact Safety, BDS 9 Armin Schwarz Q Ehrwald, Austria Eduardo Laguna, Geiser Suspension, KMC Wheels, Par Ventures, -

Red Bull Racing 1:23.619 1:21.773 1:20.981 2 S

2017 FIA Formula One™ World Championship FORMULA 1 GRAN PREMIO DE ESPAÑA PIRELLI 2017 12 – 14 May 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Time Schedule FORMULA 1 GRAN PREMIO DE ESPAÑA PIRELLI 2017 Welcome to Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya The Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya in detail Recommendations to get to Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya Media Centre Operation Formula One Press Conference Schedule 2011/2016 Spanish Grand Prix results Media Contacts FORMULA 1 GRAN PREMIO DE ESPAÑA PIRELLI 2017 Officials 2017 Circuit de Barcelona-Catalunya Race Calendar 2017 FIA Formula One World Championship™ Calendar 2017 FIA Formula One World Championship™ Entry list 2017 FIA Formula One World Championship™ Classification Drivers and Teams Statistics 2017 FIA Formula One World Championship™: Australia, China, Bahrain and Russia Appendix The Formula One Spanish Grand Prix 1913-2016 Circuit general map, grandstands and giant screens Red Zones map TIME SCHEDULE THURSDAY, 11th May 13.00 Gates and Ticket Offices Opening 16.00 - 18.30 Formula One Pit Lane Walk (with 3-day or Sunday ticket) 18:00-18:30 Go Karting Karting driver demo meet & greet F1 Drivers FRIDAY, 12th May 08.00 Gates and Ticket Offices Opening 10.00 - 11.30 Formula One 1st Practice Session 12.00 - 12.45 FIA Formula 2 Practice Session 14.00 - 15.30 Formula One 2nd Practice Session 15.55 - 16.25 FIA Formula 2 Qualifying Session 16.45 - 17.30 GP3 Series Practice Session 17.50 - 18.35 Porsche Mobil 1 Supercup Practice Session SATURDAY, 13th May 08.00 Gates and Ticket Offices Opening 09.45 - 10.15 GP3 Series Qualifying -

Video Interface for Toyota, Opel, Peugeot, Citroen Manual

Installation Manual HDMI Interface for New PEUGEOT / CITROEN car-solutions.com [email protected] car-solutions.com •Specification Compatibility: PG3008, Picasso C4 2017~ Components: Interface Main*1 Interface Input / Output specification: Input: HDMI*1 Analog RGB*1 (No USE) A/V*1 CVBS(Front Camera)*1 CVBS(Rear Camera)*1 Output: To LCD*1 AUDIO OUT*1 Power Spec: Input Power: 8VDC ~ 18VDC Consumption: 5WATT Switch input mode: 1. External video sources skip function: Able to control input videos on and off via Dip switches 2. Able to switch videos via the remote and button switch 3. Able to detect the rear view camera by CAN or rear lamp cable •Features 1. High-resolution display through HDMI input 2. Control EXT devices(DVD/DTV) via Multi Media Touch GUI 3. Adjustablecar-solutions.com screen position of external device 4. Improved Screen Display(user-oriented interface) 5. Mode switching with OEM button 6. Power output for front and rear camera drive 7. Dynamic PAS(parking assistance system) 2 [email protected] car-solutions.com •Components MAIN BOARD POWER CABLE AV CABLE LCD CABLE QCPASS1260 HARETC0298 HAVCAB0060 HLCDCA0017 TOUCH CABLE UART CABLE BUTTON CABLE REMOTE CONTROL HRGBCA0022 HARETC0144 HARETC0001 REMOTE0001 car-solutions.com 3 [email protected] car-solutions.com •DIP Switch Setting ※ ON : DOWN / OFF : UP PIN FUNCTION Dip S/W SELECT OFF : HDMI MODE 1 HDMI ON : HDMI MODE SKIP OFF : LVDS MODE 2 LVDS ON : LVDS MODE SKIP OFF : AV MODE 3 AV ON : AV MODE SKIP OFF: EXT 4 FRONT CAMERA ON: OEM OFF: CITROEN 5 CAR MODEL ON: PEUGEOT 6 N/C OFF : OEM 7 REAR CAMERA ON : EXT 8 N/C ※ Please make sure to disconnect the power cable of the interface and reconnect the power cable again to apply the dip switch setting whenever changing DIP switch. -

Automotive: PSA Peugeot Citroën

Success Story Save time tooling at PSA with OPEN MIND A great many tools have to be created to mass produce quality vehicles, and they have to be flawless. Their quality and cost are key factors in international competi- tion. The skill of the toolmakers and their machine-tool programming have a… ...crucial role to play in meeting these chal- In their search for a solution, Laurent Siffer- lenges. len, head of the process group at PSA (too- ling, CAD/CAM, quality) and Serge Locher The role of the PSA factory’s tool shop in met with Jorge de Carvalho, application en- Mulhouse involves designing and producing gineer at OPEN MIND and writer of the CAD/ aluminium foundry moulds, casting and CAM software hyperMILL®. The management stamping tools for the automotive group. was won over by hyperMILL®’s functionali- The 270 on-site professionals have access ties, ease of handling, its ability to manage to a sizable pool of CNC machines for tack complex paths, as well as its options for welding, drilling, milling and jig grinding. recording personalised macro instructions The increasing performance requirements easily, and saving them. An initial program- mean that methods and resources have to be continuously improved. This rule applies Behind an aluminium mould for casting, Serge equally to the machines’ programming. Locher (on the right) in discussion with Jorge de CAD/CAM programming software appeared Carvalho about the various ways of understan- seven years ago, bringing significant pro- About PSA Peugeot Citroën ding programming with hyperMILL®. ductivity gains. With its three world-renowned brands, Peugeot, Citroën and DS, PSA Peugeot Ci- Meeting, tests and adopting software troën sold 3 million vehicles worldwide in The PSA tool shop in Mulhouse adopted 2014.