Sudan SIGI 2019 Category N/A SIGI Value 2019 N/A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENDER PROGRAMMATIC REVIEW Sudan Country Office

GENDER PROGRAMMATIC REVIEW Sudan Country Office This independent Gender Review of the Country Programme of Cooperation Sudan-UNICEF 2013- 2017 is completed by the International Consultant: Mr Nagui Demian based in Canada matic Review UNICEF Sudan: Gender Programmatic Review Khartoum 7 July, 2017 FOREWORD The UNICEF Representative in Sudan, is pleased to present and communi- cate the final and comprehensive report of an independent gender pro- grammatic review for the country programme cycle 2013 – 2017. This review provides sounds evidence towards the progress made in Sudan in mainstreaming Gender-Based Programming and Accountability and measures the progress achieved in addressing gender inequalities. This ana- lytical report will serve as beneficial baseline for the Government, UNICEF and partners, among other stakeholders, to shape better design and priori- tisation of gender-sensitive strategies and approaches of the new country programme of cooperation 2018-2021 that will accelerate contributions to positive changes towards Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on gender equality in Sudan. The objective of the gender review was to assess the extent to which UNICEF and partners have focused on gender-sensitive programming in terms of the priorities of the Sudan’s Country Programme, financial invest- ments, key results, lessons learnt and challenges vis-à-vis the four global priorities of UNICEF’s Gender Action Plan 2014-2017. We thank all sector line ministries at federal and state levels, UN agencies, local authorities, communities and our wide range of partners for their roles during the implementation of this review. In light of the above, we encourage all policy makers, UN agencies and de- velopment partners to join efforts to ensure better design and prioritisation of gender-sensitive strategies and approaches that will accelerate the posi- tive changes towards the Goal 5 of the SDGs and national priorities related to gender equality in Sudan. -

SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa

SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 1 SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage In the Middle East and North Africa UNICEF Middle East and North Africa Regional Oce This report was developed in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and funded by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The views expressed and information contained in the report are not necessarily those of, or endorsed by, UNICEF. Acknowledgements The development of this report was a joint effort with UNICEF regional and country offices and partners, with contributions from UNFPA. Thanks to UNICEF and UNFPA Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan, Morocco and Egypt Country and Regional Offices and their partners for their collaboration and crucial inputs to the development of the report. Proposed citation: ‘Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa – Sudan Country Brief’, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Middle East and North Africa Regional Office in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (IRCW), 2017. SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 3 4 SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage SUDAN Regional Study on Child Marriage Key Recommendations Girls’ Voice and Agency Build capacity of women parliamentarians to effectively Provide financial incentives for sending girls raise and defend women-related issues in the parliament. to school through conditional cash transfers. Increase funding to NGOs for child marriage-specific programming. Household and Community Attitudes and Behaviours Engage receptive religious leaders through Legal Context dialogue and awareness workshops, and Coordinate advocacy efforts to end child marriage to link them to other organizations working on ensure the National Strategy is endorsed by the gov- child marriage, such as the Medical Council, ernment, and the Ministry of Justice completes its re- CEVAW and academic institutions. -

Algemeen Ambtsbericht Sudan

Algemeen ambtsbericht Sudan Datum juli 2015 Pagina 1 van 77 Algemeen ambtsbericht Sudan | Juli 2015 Colofon Plaats Den Haag Opgesteld door CAT Pagina 2 van 77 Algemeen ambtsbericht Sudan | Juli 2015 Inhoudsopgave Colofon ......................................................................................................2 Inhoudsopgave ............................................................................................3 1 Landeninformatie..................................................................................... 6 1.1 Politieke ontwikkelingen ................................................................................6 1.1.1 Darfur ......................................................................................................14 1.1.2 Vredesmissies............................................................................................ 15 1.2 Veiligheidssituatie ......................................................................................17 1.2.1 Documenten.............................................................................................. 29 2 Mensenrechten........................................................................................32 2.1 Juridische context ......................................................................................32 2.1.1 Verdragen en protocollen.............................................................................32 2.1.2 Nationale wetgeving ...................................................................................32 2.2 Toezicht -

Sudan Law Reform Advocacy Briefing

Sudan Law Reform Advocacy Briefing January 2014 Welcome to the fourth issue of the Sudan Law Reform Advocacy Briefing.1 This Briefing is published quarterly to highlight and reflect on law reform developments and issues critical to the promotion and protection of human rights in Sudan. Its aim is to inform and engage those working on, and interested in, law reform and human rights in Sudan. The present issue contains an annotated compilation of key recommendations made by regional and international human rights bodies, as well as states during the Universal Periodic Review process, and, in so far as available, responses by Sudan thereto. It focuses on legislative reforms, particularly in relation to serious human rights violations. This issue seeks to provide a useful reference document for all actors concerned and to identify priority areas for engagement, particularly in the context of the pending review of Sudan’s state party report by the UN Human Rights Committee. Yours, Lutz Oette For further information, please visit our dedicated project website at www.pclrs.org/ Please contact Lutz Oette (REDRESS) at [email protected] (Tel +44 20 77931777) if you wish to share information or submit your comments for consideration, or if you do not wish to receive any further issues of the advocacy briefing. 1 The Advocacy Briefings are available online at: http://www.pclrs.org/english/updates. 1 I. The implementation of international human rights treaty obligations, legislative reforms and effective protection of rights in Sudan: International perspectives and Sudan’s responses in context 1. Introduction The question of human rights in Sudan has engaged a large number of regional and international bodies. -

Constitution – Making in the Sudan: Past Experiences

Constitution – Making in the Sudan: Past Experiences Prof. Ali Suleiman Fadlall A paper presented at the Constitutionmaking Forum: A Government of Sudan Consultation 2425 May 2011 Khartoum, Sudan With support from Advisory Council for Human Rights 1 Introduction: In 1978, upon my return to Sudan from Nigeria, I found that one of my predecessors at the Faculty of Law, University of Khartoum, had set up a question in constitutional law for the first year students asking them to comment on the following statement: “Since the time of the Mahdi, the history of the Sudan has been a history of a country in search for a constitution.” In 1986, I contributed a chapter on constitutional development in the Sudan to a book of essays on the politics of the country, published under the title of Sudan Since Independence. The editors, and myself chose for my easy the heading of “The Search for a Constitution”. Now, a quarter of a century later, and more than fifty years since the country became independent, it seems that that perennial search for a constitution has not, yet, been successful concluded. In this brief essay, I intend to look at past endeavors in constitution making in this country. It is just possible that previous constitutional making processes may have been so flawed, that the structure that they thought to build could not withstand the test of time. Hence; they always came crumbling down. In some cases, some of these structures were not even finished. ConstitutionMaking: Constitutions can be created through different methods and devices. -

Sudan, Performed by the Much Loved Singer Mohamed Wardi

Confluence: 1. the junction of two rivers, especially rivers of approximately equal width; 2. an act or process of merging. Oxford English Dictionary For you oh noble grief For you oh sweet dream For you oh homeland For you oh Nile For you oh night Oh good and beautiful one Oh my charming country (…) Oh Nubian face, Oh Arabic word, Oh Black African tattoo Oh My Charming Country (Ya Baladi Ya Habbob), a poem by Sidahmed Alhardallou written in 1972, which has become one of the most popular songs of Sudan, performed by the much loved singer Mohamed Wardi. It speaks of Sudan as one land, praising the country’s diversity. EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUDANESE ORGANISATION FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT In Search of Confluence Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Sudan The Equal Rights Trust Country Report Series: 4 London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose pur- pose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust © Photos: Anwar Awad Ali Elsamani © Cover October 2014 Dafina Gueorguieva Layout: Istvan Fenyvesi PrintedDesign: in Dafinathe UK Gueorguieva by Stroma Ltd ISBN: 978-0-9573458-0-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. -

1 Chairperson, Committee on Economic, Social And

Chairperson, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights UNOG-OHCHR CH 1211 Geneva 10 Switzerland 1 October 2014 Dear Mr. Kedzia, 56th Session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights – Pre-Sessional Working Group on Sudan We are writing with a view to the pre-sessional meeting of the working group on Sudan during the 54th Session from 1-5 December 2014. Please find below a brief update of developments pertaining to the main concerns of REDRESS and the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies (ACJPS) in relation to the state party’s implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). 1 I. Renewed conflict, ongoing human rights violations and impunity The situation in Sudan since 2000, when the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights last considered a report by the State party,1 has been marked by considerable developments and changes, including the adoption of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005, the Interim National Constitution in 2005 and the independence of South Sudan in 2011. Nonetheless, most of the concerns identified in the Committee’s concluding observations of 2000 have not been adequately addressed, and several new issues of concern have arisen since. The situation in Sudan continues to be characterised by ongoing human rights violations, armed conflict, impunity and a weak rule of law. Lack of democracy, marginalisation (of the periphery and of groups within Sudan, particularly women) and weak governance are among the key factors that have contributed to this systemic crisis. -

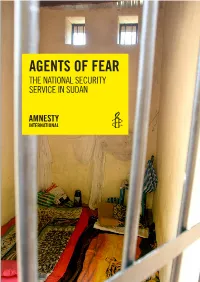

Agents of Fear

AGENTS OF FEAR THE NATIONAL SECURITY SERVICE IN SUDAN Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.8 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Amnesty International Publications First published in 2010 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Amnesty International Publications 2010 Index: AFR 54/010/2010 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. Cover photo : A cell where detainees were held by the National Intelligence and Security Service in Nyala, Sudan. This photograph was taken in 2004 during a visit of -

Child Notice Sudan

Child Notice Sudan 2016 UNICEF The Netherlands UNICEF Belgium UNICEF Sweden Co-funded by the European Union Child Notice Sudan 2016 Authors: Chris Cuninghame, Abdelrahman Mubarak, Husam Eldin Ismail, Hosen Mohamed Farah With support from: Denise Ulwor (UNICEF Sudan), Tahani Elmobasher (UNICEF Sudan), Majorie Kaandorp (UNICEF The Netherlands), Steering Committee established by National Council for Child Welfare Design: Schone Vormen Print: Impress B.V., Woerden 2016 For further information, please contact: Majorie Kaandorp Children’s Rights Advocacy Officer UNICEF The Netherlands Tel: + 31 (0)88 444 96 50 Email: [email protected] The Child Notice has been produced by UNICEF The Netherlands, UNICEF Belgium and UNICEF Sweden as part of the project Better information for durable solutions and protection which is financially supported by the Return Fund of the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the European Commission can not be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Co-funded by the European Union 2 UNICEF Child Notice Sudan The project “Better information for durable solutions and protection”, generates child-specific country of origin information analysis (Child Notices) on countries of origin of children on the move to Europe. The Child Notices describe the situation of children in the countries of origin providing legal and practical information on education, health care, child protection, armed conflict, juvenile justice, trafficking etc. The Child Notices have been developed based on this Methodology Guidance on Child Notice. The countries of origin have been chosen based on migration flows of children (with and without families), return figures, EU and national priorities. -

Sudan Report September 2017

NUMBER 3 SUDAN REPORT SEPTEMBER 2017 Girls, Child Marriage, and Education in Red Sea State, Sudan: Perspectives on Girls’ Freedom to Choose AUTHORS Samia El Nagar Sharifa Bamkar Liv Tønnessen 2 SUDAN REPORT NUMBER 3, SEPTEMBER 2017 Girls, Child Marriage, and Education in Red Sea State, Sudan: Perspectives on Girls’ Freedom to Choose Sudan report number 3, September 2017 ISSN 1890-5056 ISBN 978-82-8062-663-9 (print) ISBN 978-82-8062-664-6 (PDF) Authors Samia El Nagar Sharifa Bamkar Liv Tønnessen Cover photo Photo by Albert Gonzalez Farran, UNAMID Graphic designer Kristen Børje Hus www.cmi.no List of Tables Table 1 Age of marriage for boys in Red Sea State, Sudan, per the opinion of interviewees in researched communities Table 2 Age of marriage for girls in Red Sea State, Sudan, per the opinion of interviewees in researched communities Table 3 Reasons for the child marriage of girls, based on respondents from Red Sea State, Sudan Table 4 Family members consulted prior to child marriage, based on interviews in Red Sea State, Sudan Table 5 Consultation with girls prior to their marriage, as reported by respondents in Red Sea State, Sudan Table 6 Reasons why girls cannot refuse marriage, based on interviews in Red Sea State, Sudan Table 7 Family members taking part in decisions about bride wealth, as reported by respondents in researched communities in Red Sea State, Sudan Table 8 Conditions families place on their child daughters’ marriages, as reported by respondents from researched communities in Red Sea State, Sudan Table 9 The role of -

Third Periodical Report of the Republic of the Sudan Under Article 62 of the African Charter on Human and People’S Rights May 2006

In Name Allah The Compassionate The Merciful The Republic of the Sudan The Third Periodical Report of the Republic of the Sudan under Article 62 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights May 2006. Introduction: 1. Having ratified the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights in February 1986, the Sudan continues to endeavor to fulfill its commitments arising from the Charter, irrespective of its increasing interest in the efforts and work of the esteemed African Commission on Humans and People’s Rights and its desire to attend regularly the meetings of the commission, especially in recent years. It has also demonstrated a full cooperation with the commission, at a time when it is responding to its communications, enquiries, provision of information, and documents, receiving special rapporteurs and committees. This is thanks to its belief in the message and role of the commission in protecting and promoting the African Human and People’s Rights. This emanates from its belief in the usefulness of the objective and constructive dialog between the commission and the member states in the service of the African Human and People’s Rights and Liberties. 2. On the basis of the above, The Sudan presented its initial report on the situations of Human Rights which were discussed during the twenty first (21) session held in Nouakchott, Mauritania in April 1997. The Sudan expressed during the session some observations and came up with enquiries about some of the contents of the report. 3. Once again, and based on Article 62 of the Charter, the Sudan presented its second report in 2003 which incorporated all the reports which the Sudan was requested to present up to date. -

Sudan's Constitution of 2019

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:49 constituteproject.org Sudan's Constitution of 2019 Subsequently amended Translated by International IDEA Prepared for distribution on constituteproject.org with content generously provided by International IDEA. This document has been recompiled and reformatted using texts collected in International IDEA's ConstitutionNet. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:49 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter 1: General Provisions . 5 1. Name and Entry into Force . 5 2. Repeal and Exemption . 5 3. Supremacy of the Charter’s Provisions . 6 4. Nature of the State . 6 5. Sovereignty . 6 6. Rule of Law . 6 Chapter 2: Transitional period . 6 7. Duration of Transitional Period . 6 8. Mandate of the Transitional Period . 6 Chapter 3: Transitional Period Bodies . 8 9. Levels of Government . 8 10. Transitional Government Bodies . 8 Chapter 4: Sovereignty Council . 8 11. Composition of the Sovereignty Council . 8 12. Competencies and Powers of the Sovereignty Council . 9 13. Conditions for Membership in the Sovereignty Council . 10 14. Loss of Membership in the Sovereignty Council . 11 Chapter 5: Transitional Cabinet . 11 15. Composition of the Transitional Cabinet . 11 16. The Cabinet’s Competencies and Powers . 11 17. Conditions for Membership in the Cabinet . 12 18. Loss of Membership in the Cabinet . 12 Chapter 6: Common Provisions for Constitutional Positions . 13 19. Declaration of Assets and Prohibition of Commercial Activities . 13 20. Prohibition on Candidacy in Elections . 13 21. Challenging Actions of the Sovereignty Council and Cabinet . 13 22. Procedural Immunity . 14 23. Oath of the Chairman and Members of the Sovereignty Council and Cabinet .