Barilla Spa (A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antipasti Pasta Beverages

Antipasti Tiny lettuces, sunchokes, apple, saba, calyroad cows milk cheeses 14. Crispy brussels sprouts with blood orange, sopressata & chicory 14. Roman fried cauliflower, mint, capers, lemon 10. Gulf snapper ceviche, citrus tapenade, coriander, sweet potato chips 16. Wild calamari in Sicilian tomato brodetto with pine nuts and caperberries 14. PSM Smoked prosciutto, buttermilk piadina, my ricotta, pineapple mostarda 15. Octopus & mortadella spiedino, field peas, marsala, benne seed 17. Bruschetta banh mi, overnight pork, chicken liver, giardiniera, jalapeno 13. Pasta Baked / pan fried/ Risotto Risotto, daily MP. Crispy white lasagna slab, jalapeno pesto, crème fraiche, salanova 17. Southern fried chicken parm with creamy collards & fusilli 19. Penne al pomodoro, alta cucina tomatoes, toasted garlic, my ricotta 17. FRESH Wide pappardelle, bolognese gravy, american parm 16. 20 yolk tagliatelle with wild mushrooms, Tuscan kale kimchi & butter 19. Chicken liver ravioli, apple marmellata, ceci, scattered herbs 19. Ricotta gnocchi, winter vegetables, smoked salata, tomato passato 17. EXTRUDED / HAND- MADE Garganelli, smoked bacon, bronzed brussels sprouts, butternut, sage 18. Occhi di lupo, lamb/fennel sausage, young rapini, sardinian pecorino 19 Tortellini en brodo, rabbit cacciatore, oyster mushrooms, green olives 19. Black spaghetti, hot calabrese sausage, red shrimp, scallions 19. After Pasta Our gelati & cookies 7. Cream cheese panna cotta with marmellata, walnut & ginger snap crumble 10. Big Ry’s chocolate “éclair”, mousse, feuilletine, tree nut brittle 10. Apple upside-down cake, praline pecan gelato, oat streusel 9. Beverages Sparkling water 2.50. Soft drinks & iced tea 2. Coffee, hot tea & espresso 3. Cappuccino & latte 4. Consuming raw or undercooked shellfish, poultry or eggs may raise your risk of food-borne illness. -

Antipasti Pasta Beverages

Antipasti Buttermilk piadina, smoked prosciutto, ricotta, honey, radicchio 15. Crispy brussels sprouts, hummus, meyer lemon, french curry 13. Gulf tuna crudo, tangerine, ginger, tiny coriander, puffed middlins 17. Vegetarian caesar, bambi romaine, roasted sunchokes, hakurei, crostini 14. Wild calamari in sicilian tomato brodetto with pine nuts and caperberries 14. Roman fried cauliflower, mint, capers, lemon 11. Pork belly bruschetta, chicken liver mousse, fall kimchi, palm sugar 13. Octopus & mortadella spiedino, field peas, marsala, benne seed 17. Pasta Baked / pan fried/ Risotto Risotto, daily MP. Southern fried chicken parm with creamy collards & fusilli 19. Crispy white lasagna slab, tennessee pecorino, “tricolore” sauce 17. FRESH Squash tortelloni, guanciale, kale, sage, apple marmellata 19. Wide pappardelle, bolognese gravy, american parm 18. 20 yolk tagliatelle with wild mushrooms, Tuscan kale kimchi & butter 19. EXTRUDED / HAND- MADE Blackened red fish, soft polenta, meyer lemon butter, rainbow chard 19. BoccaLupo ramen, collard/pork belly brodo, momofuku egg, boiled peanuts 19. Occhi di lupo, lamb sausage, broccoli, smoked tomato, covington feta 19. Black spaghetti, hot calabrese sausage, red shrimp, scallions 19. After Pasta Our gelati & cookies 7. Cream cheese panna cotta with poached pear & gingersnap crumbs 8. Big Ry’s chocolate “éclair”, mousse, feuilletine, candied tree nuts 10. Caramel apple tart, brown butter gelato, pecan sandie, mascarpone 10. Beverages Sparkling water 2.50. Soft drinks & iced tea 2. Coffee, hot tea & espresso 3. Cappuccino & latte 4. Consuming raw or undercooked shellfish, poultry or eggs may raise your risk of food-borne illness. . -

Pasta Packaging

ITALFOODS Pasta Guide 2015 A BRIEF HISTORY OF PASTA - IT WASN’T MARCO POLO…. Although, Marco Polo did come across some kind of soft dough filled with meat – think steamed dumplings – in his Asian travels and though that may have ultimately led to the Italian tradition of stuffed pasta such as ravioli - Mr. Polo did not bring pasta to the Italians. It was already there. It is thought that Etrusco-Romans had a layered dish in which they used a noodle made from durum wheat – the noodle was called “lagane”. Sound familiar? Historians believe this was where modern day lasagne comes from. This food, mentioned in the first century AD, was not boiled like pasta, it was cooked in an oven. Dried and subsequently boiled pasta is thought to have arrived in Sicily with the Arabs somewhere in the eighth century. In fact it was in Palermo, Sicily that a factory began to produce dried pasta for local export in the twelfth century. Initially pasta was prepared by street vendors and eaten with ones hands. It was the common mans food and was simply served sprinkled with a little cheese. Sauce did not really come into existence until tomatoes were discovered in the New World and then brought back to Italy. Even then the people feared that the tomato was a poisonous fruit because it is a member of the Nightshade family. Inevitably pasta spread throughout the Italian peninsula and Europe due to its great shelf life and portability. Naturally when Italians migrated west to the United States they brought their culinary traditions with them. -

Pasta ($10) Meat ($15) Fish

LUNCH ONLY / 12PM-4PM / TAKE OUT ONLY / DUPONT (202-483-3070) / 14TH (202-290-1178) PASTA ($10) Add: Meat Sauce $3.99, Shrimp (5 pcs) $4.99, Chicken $6.99, Gluten free Penne, Spaghetti $4.99 - Whole Wheat Penne, Spaghetti $2.99 Penne All'arrabbiata spicy tomato sauce, garlic Penne alla Margherita fresh tomato sauce, fresh basil, mozzarella Spaghetti con Polpette di Manzo spaghetti, fresh tomato sauce, beef meatballs Capellini con Pomodoro e Basilico angel hair pasta, fresh tomato sauce, garlic, basil Fettuccine Alfredo homemade fettuccine in a parmesan cream sauce Carbonara spaghetti, onions, pancetta, black pepper, egg Cavatelli homemade cavatelli, Italian sausage, tomato sauce, parmesan, broccoli rabe Ravioli Della Nonna homemade ravioli filled with pumpkin, amaretti, butter sage sauce Cacio e Pepe homemade tagliolini, parmigiano, pecorino, black pepper, olive oil MEAT ($15) Pollo alla Milanese Milanese style breaded chicken breast, cherry tomatoes, arugula Battuta di Pollo pounded, grilled chicken breast, mixed greens, cherry tomatoes FISH ($15) Salmone alla Griglia grilled fillet of Atlantic salmon, seasonal vegetables, olives, capers PIZZA ($10) Marinara* San Marzano tomato sauce, roasted garlic, oregano. Margherita Classica San Marzano tomato sauce, fresh mozzarella, basil. Napoletana* San Marzano tomato sauce, anchovies, capers, oregano. Sofia San Marzano tomato sauce, fresh mozzarella, gorgonzola, dolci. Salami San Marzano tomato sauce, fresh mozzarella, pepperoni, mushrooms. Vegetariana* San Marzano tomato sauce, roasted bell peppers, eggplant, zucchini. Indiavolata Fresh mozzarella, Italian sausage, broccoli rabe. Without san marzano tomato sauce Caciottaro Four cheeses: mozzarella, gorgonzola, taleggio, grana. Without san marzano tomato Verdona Ricotta cheese, spinach, olives, capers, mozzarella. Without san marzano tomato sauce . -

Un'estate Freschissima

UN’ESTATE FRESCHISSIMA Le offerte di Luglio 2021 Fare la spesa non è mai stato così facile ! Pascolo Verde si rinnova con un sito completamente rivisitato e pensato per rendere più semplice la tua spesa online, da qualunque dispositivo fisso e mobile. Visitalo subito per scegliere tra oltre mille prodotti e paga comodamente con carta di credito sulla piattaforma stessa oppure alla consegna della tua spesa, tramite bancomat o contanti. La nostra logistica ci permette di consegnare gratuitamente la tua spesa online entro 24h dall’ordine in tutto il comune di Palermo. Per ordini effettuati entro le 12.00 la consegna avviene addirittura il giorno stesso, nel pomeriggio.Per il resto della provincia di Palermo e di Trapani i tempi variano da 36 a 72 h, ma qualità e puntualità restano sempre le stesse! CONSEGNA GRATUITA TRASPORTI A -20° C su tutto il territorio furgoni per freschi e surgelati CONSEGNA IN GIORNATA PAGA COME VUOI per ordini evasi entro le 12.00 carta di credito, bancomat o contanti ORDINE MINIMO 30 € FORMATI CONVENIENZA acquista solo quello che ti serve grandi formati , grande risparmio LA NOSTRA PRIMA COLAZIONE Svegliarsi col sorriso, persino di lunedì! MINI CROISSANT VUOTO CROISSANT VEGANO CROISSANT INTEGRALE SURGELATO DELIFRANCE ALL’ ARANCIA AL MIELE 50 gr x 25 pezzi SURGELATO DELIFRANCE SURGELATO DELIFRANCE 90 gr x 6 pezzi 90 gr x 12 pezzi € 4,40 € 3,75 € 6,72 CROISSANT INTEGRALE CROISSANT PLUS CROISSANT PLUS AI FRUTTI DI BOSCO ALLA CREMA ALL’ALBICOCCA SURGELATO DELIFRANCE SURGELATO ALEMAGNA SURGELATO ALEMAGNA 100 gr x 6 pezzi -

The Geography of Italian Pasta

The Geography of Italian Pasta David Alexander University of Massachusetts, Amherst Pasta is as much an institution as a food in Italy, where it has made a significant contribution to national culture. Its historical geography is one of strong regional variations based on climate, social factors, and diffusion patterns. These are considered herein; a taxonomy of pasta types is presented and illustrated in a series of maps that show regional variations. The classification scheme divides pasta into eight classes based on morphology and, where appropriate, filling. These include the spaghetti and tubular families, pasta shells, ribbon forms, short pasta, very small or “micro- pasta” types, the ravioli family of filled pasta, and the dumpling family, which includes gnocchi. Three patterns of dif- fusion of pasta types are identified: by sea, usually from the Mezzogiorno and Sicily, locally through adjacent regions, and outwards from the main centers of adoption. Many dry pasta forms are native to the south and center of Italy, while filled pasta of the ravioli family predominates north of the Apennines. Changes in the geography of pasta are re- viewed and analyzed in terms of the modern duality of culture and commercialism. Key Words: pasta, Italy, cultural geography, regional geography. Meglio ch’a panza schiatta ca ’a roba resta. peasant’s meal of a rustic vegetable soup (pultes) Better that the belly burst than food be left on that contained thick strips of dried laganæ. But the table. Apicius, in De Re Coquinaria, gave careful in- —Neapolitan proverb structions on the preparation of moist laganæ and therein lies the distinction between fresh Introduction: A Brief Historical pasta, made with eggs and flour, which became Geography of Pasta a rich person’s dish, and dried pasta, without eggs, which was the food of the common man egend has it that when Marco Polo returned (Milioni 1998). -

V = Vegetarian GF = Gluten Free = Popular Item

Fresh pastas come by the pound. Raviolis come in a count of 10. These are not yet cooked. These are not yet cooked. Traditional Bolognese $8.95 Linguine V $4.95 Veal, ground beef, carrots, celery, garlic, and tomato paste stuffed ★Pappardelle V $4.95 in fresh SPC pasta Spinach Pappardelle V $5.95 ★4-Cheese V $7.95 6621 Falls of Neuse Rd, Penne V $4.95 Shredded mozzarella, ricotta, parmesan, fresh mozzarella and Raleigh, NC 27615 Fusilli V $4.95 garlic NEW Gnocchetti V $4.95 Pumpkin V $8.95 919-900-0083 Pumpkin, ricotta and a touch of cinnamon, try it with the Pecan & Sage Pesto Sauce SouthernPasta.com ★ Bolognese GF (32oz) $7.95 Monday- Friday: 11am-7pm Marinara GF Saturday: 11am-6pm (32oz) $5.00 Sunday: 12pm-5pm Alfredo V GF (32oz) $5.95 ★ Vodka GF Order pick up and curbside (32oz) $5.95 NEW Pecan & Sage Pesto V over the phone or online. (5.5oz) $2.00 Delivery is available online only. Click here to order online. Classic Beef Meatballs 8 pack $8.95 12 pack $11.95 Bolognese Sauce V = Vegetarian GF = Gluten Free ★ = Popular Item Chicken Marsala $12.95 Breaded chicken breasts with marsala wine sauce, ★ Classic Lasagna $26.95 Entrees are made fresh daily and require garlic mashed potatoes, and seasonal roasted Traditional beef bolognese with mozzarella, heating up. vegetables ricotta, parmesan. Served with a side of 4 Meaty Lasagna $13.95 breadsticks ★ Coastal Shrimp Linguine $14.95 Your favorite classic lasagna now comes in an entrée Feeds 4-6 Shrimp, tomatoes, mushrooms & spinach on linguine size noodles tossed with a lemon-white wine -

Pasta Veal, Beef, and Fish Gelato Naturale Artigianale

Pasta Gelato Naturale Artigianale by Giorgio Pompei We prepare our handmade ravioli, gnocchi and casunziei everyday All natural ingredients and all our pasta is freshly cooked to order No artificial flavours or colours. No preservatives. No emulsifiers. Take-away menu ___________________________________________ Made fresh everyday on the premises ___________________________________________ Ravioli di magro alla tirolese (V) 25 Milk-based Gelato Ravioli filled with baby spinach, parmigiano, made with biodynamic milk __________________________ ricotta and nutmeg in a tomato or butter sauce Casunziei all’ampezzana (V) 25 Cream and caramel Organic cream and our homemade caramel Crescent shaped pasta filled with sautéed beetroot in a Salted caramel Housemade caramel and sicilian sea salt butter, poppy seed and sage parmesan sauce Pure piemonte hazelnut IGP tondo gentile hazelnuts from piemonte Gnocchi con pomodoro (V) 24 Pure bronte pistacchio Bronte pistacchio from sicily Handmade gnocchi with a fresh tomato sauce Dark chocolate 70% dark chocolate Gnocchi con Gorgonzola (V) 26 Handmade gnocchi with Gorgonzola dolcelatte Milk chocolate 40% milk chocolate pompeis Spaghetti al pomodoro (V) 21 Caffè espresso Spaghetti con burrata (V) 24 Fior di latte Biodynamic milk & cream ' Spaghetti with a fresh tomato and herb sauce Stracciatella Biodynamic milk and cream with 70% dark chocolate chips and burrata (Fresh mozzarella with a soft creamy centre) Mint and chocolate Pure mint gelato with shredded dark chocolate Spaghetti alla puttanesca 23 Capers, -

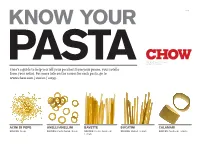

Chart-Of-Pasta-Shapes

KNOW YOUR 1 of 6 Photographs by Chris Rochelle PASTA (Images not actual size) Here’s a guide to help you tell your paccheri from your penne, your rotelle from your rotini. For more info on the sauces for each pasta, go to www.chow.com / stories / 11099. ACINI DI PEPE ANELLI/ANELLINI BAVETTE BUCatINI CALAMARI SAUCES: Soup SAUCES: Pasta Salad, Soup SAUCES: Pesto, Seafood, SAUCES: Baked, Tomato SAUCES: Seafood, Tomato Tomato Know Your Pasta 2 of 6 CAMpanELLE CAPELLINI CASARECCE CAVatELLI CAVaturI SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ (a.k.a. Angel Hair) SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Pasta Salad, Cheese, Meat, Pasta Salad, SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ Meat, Pesto, Seafood, Meat, Pasta Salad, Soup, Vegetable Vegetable Cheese, Pesto, Seafood, Tomato, Vegetable Vegetable Soup, Tomato, Vegetable CONCHIGLIE DItaLINI FarfaLLE FETTUCCINE FREGULA SAUCES: Cream/Cheese, SAUCES: Baked, Pasta Salad, SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ SAUCES: Butter/Oil, Cream/ SAUCES: Soup, Tomato Meat, Pasta Salad, Pesto, Soup Cheese, Meat, Pasta Salad, Cheese, Meat, Seafood, Tomato, Vegetable Pesto, Seafood, Soup, Tomato, Vegetable Tomato, Vegetable Know Your Pasta 3 of 6 FUSILLI FUSILLI COL BUCO FUSILLI NAPOLEtanI GEMELLI GIGLI SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, SAUCES: Baked, Butter/Oil, Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Cream/Cheese, Meat, Pasta Meat, Tomato Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, Pesto, Soup, Tomato, Salad, -

Pasta Poiatti Siciliana Confezioni Da 1 Kg

PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG Spaghetti Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N3 Maccheroncelli Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N7 Fili d’oro Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N20 Perline Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N24 PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG Cornetti Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N28 Anellini siciliani Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N33 Gnocchi sardi Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N34 Mezze penne rigate Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N37 PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG Penne rigate Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N41 Sedani grandi Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N48 Trecce Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N49 Casarecce Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N50 PASTA POIATTI SICILIANA CONFEZIONI DA 1 KG Tortiglioni Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N51 Fusilli Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N52 Rigatoni Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da 1 kg Prezzo per busta € 2.00 COD: N54 Occhi di lupo Ogni scatola contiene 12 buste da -

San Francisco | East Bay San Francisco

Bay Area Neighborhoods San Francisco | East Bay San Francisco Bernal Heights The Castro Chinatown Cole Valley Deco Ghetto Fisherman's Wharf Golden Gate Park The Haight Hayes Valley Inner Richmond Inner Sunset The Marina The Mission Mission to Potrero Dolores and Valencia Corridor 24th Street Nob Hill Noe Valley North Beach Outer Richmond Outer Sunset Pacific Heights Potrero Hill Russian Hill SoMa Tenderloin Union Square Western Addition Sights & Culture Restaurants Shopping Nightlife Map Fisherman's Wharf All San Franciscans love to hate Fisherman's Wharf. But secretly, everyone likes it a little, and having guests from out of town is the perfect excuse for cynical old-timers to go. What's It Like? All San Franciscans love to hate Fisherman's Wharf. Content never to visit the area, they complain of the tacky shops selling cheap souvenirs, the "novelty" museums whose novelty has long worn off and busloads of tourists blocking the view to Alcatraz. But secretly, everyone likes it a little, and having guests from out of town is the perfect excuse for otherwise cynical old-timers to "force" themselves to go. And it is possible to have a cheap, good time. Just avoid the wax museums and the "I'm With Stupid" T-shirt stands, and what's left are some of the best views in the city, fresh Dungeness crab and the ever-amusing sea lions. Last year, almost 12 million people made their way to the Wharf. In international surveys, it ranks as the No. 1 destination for SF-bound visitors, right ahead of Chinatown and the Golden Gate Bridge. -

THE HIGHLANDS HAPPENINGS the Highlands at Wyomissing Weekly Newspaper Wyomissing, PA July 16, 2021

THE HIGHLANDS HAPPENINGS The Highlands at Wyomissing Weekly Newspaper Wyomissing, PA July 16, 2021 HIGHLANDS UPCOMING ATTRACTIONS Residents of The Highlands are very active members of our surrounding community. As such, we understand your schedules are full of volunteering, doctors’ appointments, social events, and more. To better encourage engagement and being conscious of your time, the Programming Department is excited to announce an enhancement to program advertisement. In the Mailroom on the bulletin board, you will find a document titled “Highlands Upcoming Attractions.” This document provides residents information about all of the upcoming programs, trips, and socials scheduled for the upcoming months thereby allowing residents to save the date. Full details about each event will be included in the Highlands Happenings closer to the event date. Registration for events will begin once officially advertised in the Highlands Happenings. THE HIGHLANDS’ WEEKLY PSA invited to select vegetables from the table to spruce up their summer As we are in the middle of the dog days of summer, it can reach north salads, lunches, dinners or just for a health snack. Bring your own bag. of 90 degrees during the daytime and in the low 80s at night. Senior Please note that there may be days when there are no vegetables adults’ bodies have trouble regulating their internal body temperature available for sharing. In that case, residents can check again on another making residents more susceptible to overheat. While taking a break day to see what vegetables have appeared. from outside heat, here are some tips to make the inside of your home cooler.