The “Rendez-Vous Manqués” of Francophone and Anglophone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

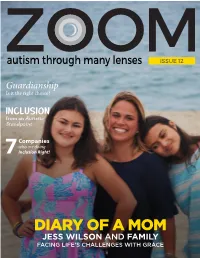

Diary of a Mom Jess Wilson and Family Facing Life’S Challenges with Grace ZOOM Autism Through Many Lenses 1 ISSUE 12 to W O

autism through many lenses ISSUE 12 Guardianship Is it the right choice? INCLUSION from an Autistic Standpoint Companies who are doing 7 Inclusion Right! DIARY OF A MOM JESS WILSON AND FAMILY FACING LIFe’s CHALLENGES WITH GRACE ZOOM Autism through Many Lenses 1 ISSUE 12 TO W O FOUNDERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes Jodi Murphy H PUBLISHERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Sharon Fuentes EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Sharon Cummings Cover photo provided and shared with permission by Jess Wilson. Sev- ART DIRECTOR eral photos throughout the magazine Suzanne Chanesman courtesy of Pixabay and Morguefile. CopY EDITOR For submission/writing guidelines, Jennifer Gaidos please review the information on our website. For our Media Kit, WEBSITE DESIGNER & WEBMASTER advertising information, questions Elizabeth Roy or comments, email us at [email protected]. PROJECT CooRDINATOR/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER Zoom Autism Magazine LLC, its Conner Cummings founders, directors, editors and contributors are not responsible ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS in any way for the actions or results Alex Plank Dena Gassner taken by any person, organization Barb Rentenbach Michael Buckholtz or party on the basis of reading Carol Greenburg Stephen Shore information, stories or contributions in this publication, website or related 3 WAYS TO READ ZOOM MAGAZINE! YOU CHOOSE! products. This publication is not intended to give specific advice SPECIAL THANKS to your specific situation. This autism through many lenses ISSUE 12 Guardianship publication should be viewed as Is it the right choice? INCLUSION from an Autistic entertainment only, and you are Maripat Robison, Dr. William Harrison, Standpoint Companies who are doing encouraged to consult a professional Ron and Owen Suskind, David Finch, 7 Inclusion Right! for specific advice. -

Disabling Composition: Toward a 21St-Century, Synaesthetic Theory of Writing

Disabling Composition: Toward a 21st-Century, Synaesthetic Theory of Writing Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Melanie Yergeau Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Brenda Brueggemann, Advisor Cynthia Selfe, Advisor H. Lewis Ulman Copyright by Melanie Yergeau 2011 Abstract My dissertation examines the ways in which composition pedagogies have, both in theory and in practice, systematically worked to exclude individuals with disabilities. Persisting in composition studies is the ideological belief that traditional writing and intelligence are somehow inherently linked, that traditional literacy is central to defining one’s intellectual worth. This privileging of composing as print-based, I contend, masks the notion that writing is simply one among many systems of making and conveying meaning, that among our readers are those who cannot always access the messages delivered within print-based texts. I argue that disability studies can enable us to reconceive the rhetorical triangle and what it means to compose. Disability studies allows us to perceive the ways in which traditional writing—and composition studies’ investment in traditional writing— normalizes and has been normalized by our understanding of “the” rhetorical triangle. But disability studies also allows us to regard the ways in which multimodal composing normalizes and has been normalized by our understanding of “the” rhetorical triangle. In order to create the inclusive, radically welcoming pedagogy that so many teacher- scholars strive for, I suggest that we disable composition studies—what we think we know about composers, composing, and composition(s). -

Know Yourself—The Key to a Better Life

Presents The Jody Acford Spirit Conference 2016 Know Yourself—The Key to a Better Life Annual Conference for Neurodivergent* Adults (*Those with Asperger Syndrome and related autism profiles) Saturday, September 17, 2016 ~ 9:30 am–4:30 pm Newton-Wellesley Hospital Bowles Conference Center 2014 Washington Street Newton, MA Keynote Speaker: Lydia X. Z. Brown Neurodiversity and the Autism Rights Movement Please join us in thanking the Burgay family who are generously underwriting this conference. About the Conference The Jody Acford Spirit Conference 2016—Know Yourself: The Key to a Better Life—is AANE’s 10th annual conference designed exclusively for neurodivergent* adults (post-high school and older). (*Those with Asperger Syndrome and related autism profiles). Headlined by a dynamic keynote speaker and combining a diverse program of workshops, networking and social connections, we hope this conference will leave you knowing yourself better, having learned practical strategies to improve your life and, more importantly, knowing that you are not alone. We look forward to seeing you at the conference! Keynote Presentation: Neurodiversity and the Autism Rights Movement (As described by Lydia Brown) Flapping, spinning, rocking, and humming, we autistic people are everywhere. But most representations of autistic and other disabled people are related to inspirational stories of overcomers and supercrips, and most discussions of autism and disability are limited to patronizing awareness laced with pity and fear-mongering campaigns to cure the “low-functioning” and “mentally challenged.” Too often, disability is thought of as someone else’s private medical problem instead of a diversity and social justice imperative for everyone in society. -

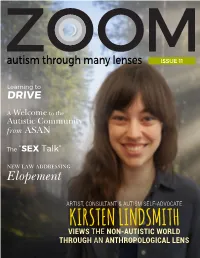

Autism Through Many Lenses ISSUE 11

autism through many lenses ISSUE 11 Learning to DRIVE A Welcome to the Autistic Community from ASAN The “SEX Talk” NEW LAW ADDRESSING Elopement ARTIST, CONSULTANT & AUTISM SELF-ADVOCATE KIRSTEN LINDSMITH VIEWS THE NON-AUTISTIC WORLD THROUGH AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL LENS ZOOM Autism through Many Lenses 1 ISSUE 11 TO W O FOUNDERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes Jodi Murphy H PUBLISHERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Sharon Fuentes EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Sharon Cummings Cover photo provided and shared with permission by Kirsten ART DIRECTOR Lindsmith. Several photos through- Suzanne Chanesman out the magazine courtesy of Pixabay and Morguefile. CopY EDITOR Jennifer Gaidos For submission/writing guidelines, please review the information on WEBSITE DESIGNER & WEBMASTER our website. For our Media Kit, Elizabeth Roy advertising information, questions or comments, email us at PROJECT CoordiNATOR/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER [email protected]. Conner Cummings Zoom Autism Magazine LLC, its AdvisorY BOARD MEMBERS founders, directors, editors and contributors are not responsible Alex Plank Dena Gassner in any way for the actions or results Barb Rentenbach Michael Buckholtz taken by any person, organization Carol Greenburg Stephen Shore or party on the basis of reading information, stories or contributions 3 WAYS TO READ ZOOM MAGAZINE! YOU CHOOSE! in this publication, website or related products. This publication is not intended to give specific advice SPECIAL THANKS to your specific situation. This publication should be viewed as Maripat Robison, Dr. William Harrison, entertainment only, and you are Ron and Owen Suskind, David Finch, encouraged to consult a professional Ed Zeitlin, Mark Friese, Conner Cummings, for specific advice. Roger Fuentes, Jacob Fuentes, Bella Fuentes and all the others who contribute in so many ways No part of this publication may be by writing, promoting, acting as ambassadors copied in any form or by any means READ ONLINE READ ON IPAD DOWNLOAD PDF and rolling up their sleeves wherever needed. -

Meaningful Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum in Multiple Settings

Meaningful Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum in Multiple Settings Teal Benevides, PhD, MS, OTR/L Anita Lesko, BSN, RN, MS, CRNA Stephen Shore, EdD Objectives ● Discuss the process of engaging the autistic adult community in defining research priorities. ● Link lessons learned in the AASET Project to other research and practice settings. ● Share examples of lessons learned to inform research, practice, and policy. ● Provide opportunity for discussion. 2 Identity-First versus Person-First Language ● We are using identity-first language in place of person-first language. ● Many stakeholders in our project prefer identity-first language that does not separate their experience of autism from who they are. ● This is an acceptable convention self-advocates use in print descriptions. ● It is important to ask the individuals you are working with whether they prefer to be identified as a ‘person with autism’ or as ‘autistic’. ● Our approach values autonomy and identity, and conveys mutual respect. 3 Funding Acknowledgment Autistic Adults and other Stakeholders Engage Together (AASET) was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Eugene Washington PCORI Engagement Award (EAIN# 4208). The views presented in this presentation are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. 4 What is AASET? Autistic Adults and other Stakeholders Engage Together Autistic adults have multiple, chronic, and potentially preventable healthcare needs as compared to same-aged adults without ASD, but we know very little about why these differences are occurring and how to improve outcomes. -

Narratives of Asperger's Syndrome in the Twenty-First Century

REWIRING DIFFERENCE AND DISABILITY: NARRATIVES OF ASPERGER'S SYNDROME IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY Neil Shepard A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Committee: Vivian Patraka Advisor Geoffrey Howes Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Victoria Ekstrand ii ABSTRACT Vivian Patraka, Advisor This dissertation explores representations of Asperger’s syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder. Specifically, it textually analyzes cultural representations with the goal of identifying specific narratives that have become dominant in the public sphere. Beginning in 2001, with Wired magazine’s article by Steve Silberman entitled “The Geek Syndrome” as the starting point, this dissertation demonstrates how certain values have been linked to Asperger’s syndrome: namely the association between this disorder and hyper-intelligent, socially awkward personas. Narratives about Asperger’s have taken to medicalizing not only genius (as figures such as Newton and Einstein receive speculative posthumous diagnoses) but also to medicalizing a particular brand of new economy, information-age genius. The types of individuals often suggested as representative Asperger’s subjects can be stereotyped as the casual term “geek syndrome” suggests: technologically savvy, successful “nerds.” On the surface, increased public awareness of Asperger’s syndrome combined with the representation has created positive momentum for acceptance of high functioning autism. In a cultural moment that suggests “geek chic,” Asperger’s syndrome has undergone a critical shift in value that seems unimaginable even 10 years ago. This shift has worked to undo some of the stigma attached to this specific form of autism. -

Meaningful Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum

2018 Autism Awareness Month: Coffee Talk Meaningful Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum April 30, 2018 1:00-2:00PM ET For audio: 888-757-2790 | Passcode: 105799 Quick Overview, How to Use Web Technology • Press *6 to mute/unmute your line. Please mute your phone lines now and adjust the volume on your computers. • If you need to step away from the phone, please do not put the call on hold. Hang up and join again • Asking a Question – You can type your questions into the chat box (shown right) – Raise your hand. Using the icon at the top of your screen (example shown right) Over the next hour… • Overview of AASET • Key strategies for meaningful inclusion of people on the Autism Spectrum in multiple settings • Discussion and Q&A • Evaluations April 25, 2018 3 Stephen Shore, EdD Teal Benevides, PhD, MS, OTR/L April 30, 2018 4 Meaningful Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum Stephen Shore, EdD Teal Benevides, PhD, MS, OTR/L www.autistichealth.org Objectives ● Provide an overview of the AASET (Autistic Adults and other Stakeholders Engage Together) project and lessons learned ● Discuss additional key strategies for meaningful inclusion of people on the autism spectrum in multiple settings ● Support dialogue between attendees and AASET project leads 6 Identity-First versus Person-First Language ● We are using identity-first language in place of person-first language. ● Many stakeholders in our project prefer identity-first language that does not separate their experience of autism from who they are. ● This is an acceptable convention self-advocates use in print descriptions. -

Autistic Adults and Other Stakeholders Engage Together Lay Conference Summary Report Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Engagement Award EAIN#4208

1 Autistic Adults and other Stakeholders Engage Together Lay Conference Summary Report Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Engagement Award EAIN#4208 Background What: Autistic Adults and other Stakeholders Engage Together (AASET) Year 2 Meeting When & Where: November 10, 2018 at the Renaissance Hotel in Washington, D.C. Objectives of Meeting: 1. Discuss research priorities to address health for autistic adults1 learned through a PCORI Engagement Award. 2. Identify best practices for engaging the autistic adult community in collaborative partnerships and research. 3. Develop an action-oriented plan to address research priorities through collective impact. Conference Summary Overview of Meeting This was the second annual meeting for AASET, and it aimed to build engagement between researchers, partner organizations and the autism community to discuss priorities for future research and engaging autistic adults authentically in the research process. We collaborated with the Association of University Centers of Disability (AUCD) to host the meeting the day prior to their annual meeting. Attendees 80 attendees registered for the meeting, which was our maximum registration. Of the 80 registrants, 64 (80%) attended. Of the 64 attendees*: o 37% were autistic adults o 24% were family /caregivers/support person of an individual on the spectrum o 41% were academic researchers o 8% were academic affiliates o 22% were representatives of disability organization *Note: Many attendees fell into more than 1 category; percentages don’t add up to 100 because people could select more than one option. Materials Provided in Advance of the Meeting Attendees received an email with detailed information about the meeting. Our attendee “Meeting Information and Accessibility Guide” (see Appendix) was provided 1 week before the meeting to assist attendees in understanding what the meeting was about, and what to expect at the meeting. -

FAU CARD Spring 2017 Newsletter

FAU CARD Spring 2017 Newsletter FAU CARD CALENdar OF EVENTS Executive Director’s Message UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED, ALL TRAININGS WILL ALSO BE AVAILABLE ONLINE JANuarY APRIL JAN 12 iRISE2 Mentoring Orientation - Boca APR 1 Family Connections Conference Dear CARD Families, Raton Campus APR 10 iRISE2 Mentoring Orientation - Boca JAN 12 Adult Social Group - Treasure Coast Raton Campus JAN 13 Little Owls Early Intervention Initiative APR 13 Autism Speaker Series: John Miller Bullying of students with autism can take many forms, all of them bad. We see students physically JAN 13 Executive Functioning APR 13 Adult Social Group - Treasure Coast bullied, punched, pushed around and even injured while others are subject to unrelenting emotional JAN 17 Community Developmental Screening APR 17 Adult Social Group - Boca Raton bullying from one student or even from groups of students. An increasing trend is for students to Clinic APR 20 Jupiter iRISE² Mentor Orientation be bullied over the Internet or with their cell phones. Each form is harmful and makes the kinds of JAN 23 Adult Social Group - Boca Raton APR 27 IEP Series: Effective Parent-Teacher progress we hope for in social capacity so much more difficult. JAN 26 Vocational Rehabilitation Transition Conferences Services JAN 26 Hangout Group - Dinning and Dating FAU CARD staff have been busy recently hosting a series of three Anti-Bullying Focus Groups and MAY with Etiquette MAY 5 FAU CARD Mental Health Conference two Anti-Bullying presentations. For the focus groups, we did one group in Delray, another on the MAY 10 iRISE2 Mentoring Orientation - Boca FAU Jupiter campus and a third at the Indian River State College in Port St. -

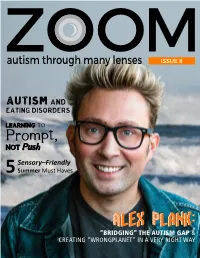

Autism Through Many Lenses ISSUE 8

autism through many lenses ISSUE 8 AUTISM AND EATING DISORDERS LEARNING TO Prompt, NOT Push Sensory–Friendly 5 Summer Must Haves “Bridging” THE AUTISM GAP & CREATING “WrongPlanet” IN A VERY RIGHT WAY ZOOM Autism through Many Lenses 1 ISSUE 8 TO W O FOUNDERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes Jodi Murphy H PUBLISHERS Sharon Cummings Sharon Fuentes EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Sharon Fuentes EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Sharon Cummings Cover photo and other pictures of Alex Plank shared with his permis- ART DIRECTOR sion. Several photos throughout the Suzanne Chanesman magazine courtesy of Pixabay and Morguefile. CopY EDITOR Jennifer Gaidos For submission/writing guidelines, please review the information on WEBSITE DESIGNER & WEBMASTER our website. For our Media Kit, Elizabeth Roy advertising information, questions or comments, email us at ADMINISTRATIVE AIDE [email protected]. Roger Fuentes Zoom Autism Magazine LLC, its PROJECT CooRDINATOR/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER founders, directors, editors and Conner Cummings contributors are not responsible in any way for the actions or results FEATURED CoLUMNIST taken by any person, organization or party on the basis of reading David Finch Maripat Robison 3 WAYS TO READ ZOOM MAGAZINE! YOU CHOOSE! information, stories or contributions Ed Zetlin & Mark Friese in this publication, website or related products. This publication is not REGULAR CoNTRIBUTORS & ADVISORS intended to give specific advice Anita Lesko Haley Moss to your specific situation. This Barb Rentenbach Jacob Fuentes publication should be viewed as entertainment only, and you are CarolAnn Edscorn Jennifer O’Toole encouraged to consult a professional Conner Cummings Lydia Wayman for specific advice. Cynthia Kim Steve Andrews No part of this publication may be copied in any form or by any means READ ONLINE READ ON IPAD DOWNLOAD PDF without written permission from WITH FREE JOOMAG APP Zoom Autism Magazine LLC.