The Complete Hedgehog Foreword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables

Game Room Tables 2020 Game Room Tables At SilverLine, our goal is to build fine furniture that will be a family heirloom – for your family and your children’s families, in the old world tradition of our ancestors. Manufactured with quality North American hardwoods, our pool tables and game tables are handcrafted and constructed for years of play. We have several styles and sizes available. Can’t find the perfect table or accessory? Let us create a piece of furniture just for you! Pool tables feature: • 1" framed slate • 22oz. cloth in over 20 colors • 12 pocket choices • Available in 7', 8', or 9' lengths Our tables are available in many custom finishes, or we can match your existing furniture. SILVERLINE, INC 2 game room furniture | 2020 Index POOL TABLES Breckenridge ................................................. 4 CHESS TABLES Caldwell ........................................................ 4 Allendale Chess Table ................................... 14 Caledonia ....................................................... 5 Ashton Chess Table ....................................... 14 Classic Mission ............................................... 5 Landmark Mission ......................................... 6 FOOSBALL Monroe .......................................................... 6 Alpine Foosball Table ................................... 15 Regal ............................................................. 7 Signature Mission Foosball Table .................. 15 Shaker Hill .................................................... 7 -

3 After the Tournament

Important Dates for 2018-19 Important Changes early Sept. Chess Manual & Rule Book posted online TERMS & CONDITIONS November 1 Preliminary list of entries posted online V-E-3 Removes all restrictions on pairing teams at the state December 1 Official Entry due tournament. The result will be that teams from the same Official Entry should be submitted online by conference may be paired in any round. your school’s official representative. V- E-6 Provides that sectional tournament will only be paired There is no entry fee, but late entries will incur after registration is complete so that last-minute with- a $100 late fee. drawals can be taken into account. December 1 Updated list of entries posted online IX-G-4 Clarifies that the use of a smartwatch by a player is ille- gal, with penalties similar to the use of a cell phone. December 1 List of Participants form available online Contact your activities director for your login ID and password. VII-C-1,4,5,6 and VIII-D-1,2,4 Failure to fill out this form by the deadline con- Eliminates individual awards at all levels of the stitutes withdrawal from the tournament. tournament. Eliminates the requirement that a player stay on one board for the entire tournament. Allows January 2 Required rules video posted players to shift up and down to a different board, while January 16 Deadline to view online rules presentation remaining in the "Strength Order" declared by the Deadline to submit List of Participants (final coach prior to the start of the tournament. -

January - April 2020 Program Brochure

JANUARY - APRIL 2020 PROGRAM BROCHURE EXPLORE THE OCEAN ABOARD A MOBILE VIRTUAL Town Hall SUBMARINE (GRADES 4-8) & (GRADES 9-12) 10 Central Street DETAILS INSIDE BROCHURE! Manchester MA 01944 Office Number: 978.526.2019 Fax Number: 978.526.2007 www.mbtsrec.com Director: Cheryl Marshall Program Director: Heather DePriest FEEDBACK How are we doing? If you have any comments, concerns or suggestions that might be helpful to us, please let us know! Call us at 978-526-2019 or email the Parks & Recreation Director, Cheryl Marshall at [email protected] MISSION: Manchester Parks & Recreation strives to offer programs and services that help to enhance quality of life through parks and exceptional recreation experiences. We provide opportunities for all residents to live, grow and develop into healthy, contributing members of our community. Whatever your age, ability or interest we have something for you! REGISTRATION INFORMATION HOWHOW TOTO REGISTERREGISTER FORFOR OUROUR PROGRAMS:PROGRAMS: Online: www.mbts.com You will need a username and password in order to utilize the online program registration system. Online registration is live. Walk in: Manchester by-the-Sea Recreation Town Hall 10 Central St Manchester. Payments can be made by check, credit card or cash. All payments are due at time of registration. Mail in: Manchester by-the-Sea Recreation Town Hall 10 Central St Manchester, MA 01944. A completed program waiver must be sent in along with full payment. Please do not send cash. Checks should be made out to Town of Manchester. If paying with a check, please indicate the program registering for in the memo & amounts. -

A Battle Royale

A Battle Royale In a previous article I looked at a game between 23... d7 two legendary Hoosier players and the theme XABCDEFGHY centered upon a far advanced pawn. Should 8-+r+-+k+( one attack, or try to queen the pawn? 7zpp+rwQpzpp' Here we will revisit this theme as it often comes 6-+-zP-+-+& into play. The question revolves about how 5+-+-sn-+-% much can you sacrifice in order to get that pawn to the promised land. 4-+-+Nwq-+$ 3+-+-+-+P# Before we get to the game, let me give you an exercise: [See the diagram at right.] 2PzP-+-zP-+" 1+K+RtR-+-! Your queen has just been attacked. Give yourself 15 minutes and decide upon what best xabcdefghy play might be, and how would you play? [What pair of Hoosiers have played the most games against each other? I would venture to say that two legendary players from Kokomo; John Roush and Phil Meyers would be my guess. I'd say they have probably crossed swords over the board more than a thousand times! (Especially when you include their marathon blitz sessions!) I witnessed their most recent battle royale at the recent Super Tornado organized by Nate Bush in Indianapolis at the Delta Hotel. But I'm also sure that by the time you are reading this that they will already have played many more games at the Kokomo IHOP in their ongoing journey across the chessboard. This encounter was played at a very fast time control [g45+5], but that might have seemed slow to these battle tested veterans. -

A Game of Love and Chess: a Study of Chess Players on Gothic Ivory Mirror Cases

A GAME OF LOVE AND CHESS: A STUDY OF CHESS PLAYERS ON GOTHIC IVORY MIRROR CASES A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College In partial fulfillment of the requirements For University Honors By Caitlin Binkhorst May, 2013 Thesis written by Caitlin Binkhorst Approved by _____________________________________________________________________, Advisor _________________________________________________, Director, Department of Art Accepted by ___________________________________________________, Dean, Honors College ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………....... v LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………………..... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………….. 1 II. ANALYSIS OF THE “CHESS PLAYER” MIRROR CASES………. 6 III. WHY SO SIMILAR? ........................................................................ 23 IV. CONECTIONS OF THE “CHESS PLAYER” MIRROR CASES TO CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE ...………………………………. 31 V. THE CONTENT OF THE PIECE: CHESS ………………………...... 44 VI. CONCLUSION……………………………………………………….. 55 FIGURES………………………………………………………………………………. 67 WORKS CITED……………………………………………………………………….. 99 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude for all those who have helped me through this project over the past two years. First, I would like to thank my wonderful advisor Dr. Diane Scillia, who has inspired me to think about this period of art in a whole new way, and think outside of what past researchers have put together. I would also like to thank the members of my committee Dr. Levinson, Sara Newman, and Dr. Gus Medicus, as well as my other art history professors at Kent State, Dr. Carol Salus, and Dr. Fred Smith who have all broadened my mind and each made me think about art in an entirely different way. Furthermore, I would like to thank my professors in crafts, Janice Lessman-Moss and Kathleen Browne who have always reminded me to think about how art is made, but also how art functions in daily life. -

TOURNAMENT Col

THE MATCH BEGINS! - - - * - - - * FIRST 6 GAMES DRAWN * ( ~ P. 82) Q: UNITED STATES Volume XXI Number 4 April, 1966 EDITOR: J . F. Reinhardt THE MATCH BEGINS The title match between defending champion Tigran Petrosian and the challenger, CHE S S F E D E RATION Boris Spas.sky. began in Moscow on April 1l. The match will, if it goes the Cull distance, consist of twenty·four games. PRESIDENT As wc go to press, six games have been completed _ all of them draws. Lt. Col. E. B. Edmondson Spassky had white in the fi rst game and opened wi th L P·K4. Petrosian re plied with the Caro-Kann, defended well, and proposed a draw after Spassky's 37th VICE·PRESIDENT move. The offer was accepted. David Hoffmann The second game, with Petrosian as white, was a Queen's Gambit Declined. REGIONAL VICE·PRE SIDENTS Although the Champion had a favorable position and an extra pawn, he was unable to make headway, and the draw was agreed to after 50 moves of piay. NEW ENGLAND Stanley King Harold Dondls The fifth game of the match was a real test of Petrosian's famou~ defensive Ell Ho u rdon ability. Spassky, playing white, reached an advantageous position at the adjournment, EAS TERN Donald Schult~ LewIs E. Wood being a pawn ahead. Soviet experts believe that the Challenger missed a winning Uober! LaBelle line on his 50th move. After this, the defense pr oved impregnable and the game MID·A T LANT IC Wlll!~m Bragg was dr awn after 79 moves. -

1992, Russia, the City of Orel. I Am a 23-Year-Old Student and I Am Fond of Playing Chess

1992, Russia, the city of Orel. I am a 23-year-old student and I am fond of playing chess. My dream is to win the "Turgenev Prize", a round-robin tournament named after the famous writer. However, the 11 opponents I have to face don't care much about my dream. In the 9th round, Semyon Mikhailovich sits at the table across from me. He is at least 50 years wiser than me. Having the advantage of playing white, he is a strong, but a good- natured and smiling opponent, despite the fact that some accident left him with only one eye. The old man starts confidently, moving the d- and c-pawns forward. I very soon manage to attack one of them, but it’s nothing dangerous yet. The most reasonable thing White can do now is to advance the e-pawn to e3. My plans to outnumber the opponent’s army would shatter at that move, but to tell the truth I have not expected an easy victory. But wait, what is happening? Semyon Mikhailovich's hand is reaching out to the f2 pawn just next to the right one and throwing it forward. They are so similar, these white pawns standing in a row. A moment later, the old man looks over the new position with his single eye and bursts out swearing. "You wanted to play e3, but grabbed the wrong pawn, right?" I ask. "Yes, of course...," the old man's shakes his head sadly. "You can take it back," the words slip out of my mouth before I have time to think about what I am saying. -

The Chess Players

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2013 The hesC s Players Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Fiction Commons, Leisure Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wolfson-Grande, Gerry A., "The heC ss Players" (2013). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 38. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/38 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chess Players A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Mentor: Dr. Philip F. Deaver Reader: Dr. Steve Phelan Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Chess Players By Gerry A. Wolfson-Grande May, 2013 Project Approved: ______________________________________ Mentor ______________________________________ Reader ______________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ______________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Acknowledgments I would like to thank several of my MLS professors for providing the opportunity and encouragement—and in some cases a very long rope—to apply my chosen topic to -

Fide Arbiters' Commission Arbiters' Manual 2013

FIDE ARBITERS’ COMMISSION ARBITERS’ MANUAL 2013 CONTENTS: A short history of the Laws of Chess page 3 FIDE Laws of Chess page 5 Preface page 5 Basic Rules page 5 Competition Rules page 15 Appendices page 29 Rapidplay page 29 Blitz page 30 Algebraic notation page 31 Quick play finish without an arbiter page 33 Blind and Visually handicapped players page 33 Chess 960 Rules page 35 Adjourned Games page 37 Types of Tournaments page 39 Swiss System page 40 Tie‐break Systems page 47 FIDE Tournament Rules page 56 Varma Tables page 63 FIDE Title Regulations page 66 Table of direct titles page 83 Guideline for norm checking page 85 FIDE Rating Regulations page 87 Regulations for the Title of Arbiters page 94 The role of the Arbiters and their duties page 99 Application forms page 103 2 A short history of the Laws of Chess FIDE was founded in Paris on 20 July 1924 and one of its main programs was to unify the rules of the game. The first official rules for chess had been published in 1929 in French language. An update of the rules was published (once more in French language) in 1952 with the amendments of FIDE General Assembly. After another edition in 1966 with comments to the rules, finally in 1974 the Permanent Rules Commission published the first English edition with new interpretations and some amendments. In the following years the Permanent Rules Commission made some more changes, based on experience from competitions. The last major change was made in 2001 when the ‘more or less’ actual Laws of Chess had been written and split in three parts: the Basic Rules of Play, the Competition Rules and Appendices. -

Fall 2008 Missouri Chess Bulletin

Missouri Chess Bulletin Missouri Chess Association www.mochess.org GM Benjamin Finegold GM Yasser Seirawan Volume 39 Number two —Summer/Fall 2012 Issue K Serving Missouri Chess Since 1973 Q TABLE OF CONTENTS ~Volume 39 Number 2 - Summer/Fall 2012~ Recent News in Missouri Chess ................................................................... Pg 3 From the Editor .................................................................................................. Pg 4 Tournament Winners ....................................................................................... Pg 5 There Goes Another Forty Years ................................................................... Pg 6-7 ~ John Skelton STLCCSC GM-in-Residence (Cover Story) ............................................... Pg 8 ~ Mike Wilmering World Chess Hall of Fame Exhibits ............................................................ Pg 9 Chess Clubs around the State ........................................................................ Pg 9 2012 Missouri Chess Festival ......................................................................... Pg 10-11 ~ Thomas Rehmeier Dog Days Open ................................................................................................. Pg 12-13 ~ Tim Nesham Top Missouri Chess Players ............................................................................ Pg 14 Chess Puzzles ..................................................................................................... Pg 15 Recent Games from Missouri Players ........................................................ -

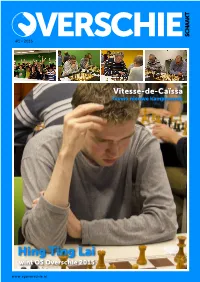

Overschie Schaakt Februari 2016

#1 • 2016 Laat uw verzekeringen doorlichten en krijg een onafhankelijk en vrijblijvend advies [email protected] Prins Mauritssingel 76c - 3043 PJ Rotterdam T 010 - 262 25 59 - M 06 -2757 0696 Overschie Schaakt februari 2016 Inhoud Verenigingsinformatie ________________________ 2 Algemeen ___________________________________ 2 3 Bestuur _____________________________________ 2 Wist u dat …? Trainers ____________________________________ 2 Deze keer in ‘Wist u dat …?’ Clubblad ____________________________________ 2 Website ____________________________________ 2 één van de beste schakers Contributie __________________________________ 2 aller tijden: Anatoli Karpov. Opzegging van het Lidmaatschap ________________ 2 Kortjes _____________________________________ 3 Agenda _____________________________________ 3 Schaken en Auteursrecht _______________________ 3 Actiefoto ____________________________________ 3 Wist u dat Anatoli Karpov …? ___________________ 3 Rectificatie __________________________________ 3 Overschie 1 _________________________________ 4 9 Bespiegelingen _______________________________ 4 Ronde 3, Souburg (uit) _________________________ 4 Overschie 2 Statistieken na Ronde 3 ________________________ 6 De strijd in RSB klasse 1A is Ronde 4, Charlois Europoort (thuis) _______________ 6 nog in volle gang. Ook voor Statistieken na Ronde 4 ________________________ 7 ons tweede team is het nog Ronde 5, CSV (uit) ____________________________ 8 spannend. De degradatielijn Statistieken na Ronde 5 ________________________ 9 -

A Proposed Heuristic for a Computer Chess Program

A Proposed Heuristic for a Computer Chess Program copyright (c) 2013 John L. Jerz [email protected] Fairfax, Virginia Independent Scholar MS Systems Engineering, Virginia Tech, 2000 MS Electrical Engineering, Virginia Tech, 1995 BS Electrical Engineering, Virginia Tech, 1988 December 31, 2013 Abstract How might we manage the attention of a computer chess program in order to play a stronger positional game of chess? A new heuristic is proposed, based in part on the Weick organizing model. We evaluate the 'health' of a game position from a Systems perspective, using a dynamic model of the interaction of the pieces. The identification and management of stressors and the construction of resilient positions allow effective postponements for less-promising game continuations due to the perceived presence of adaptive capacity and sustainable development. We calculate and maintain a database of potential mobility for each chess piece 3 moves into the future, for each position we evaluate. We determine the likely restrictions placed on the future mobility of the pieces based on the attack paths of the lower-valued enemy pieces. Knowledge is derived from Foucault's and Znosko-Borovsky's conceptions of dynamic power relations. We develop coherent strategic scenarios based on guidance obtained from the vital Vickers/Bossel/Max- Neef diagnostic indicators. Archer's pragmatic 'internal conversation' provides the mechanism for our artificially intelligent thought process. Initial but incomplete results are presented. keywords: complexity, chess, game