GOD BETWEEN the LINES GOD BETWEEN God Between the Lines Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES and the LANGUAGE of POLITICS in LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(L921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT and REACTION

MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL(l921-194?); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL BY KOUSHIKIDASGUPTA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF GOUR BANGA MALDA UPERVISOR PROFESSOR I. SARKAR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL RAJA RAMMOHANPUR, DARJEELING WEST BENGAL 2011 IK 35 229^ I ^ pro 'J"^') 2?557i UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL Raja Rammohunpur P.O. North Bengal University Dist. Darjeeling - 734013 West Bengal (India) • Phone : 0353 - 2776351 Ref. No Date y.hU. CERTIFICATE OF GUIDE AND SUPERVISOR Certified that the Ph.D. thesis prepared by Koushiki Dasgupta on Minor Political Parties and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial Bengal ^921-194'^ J Attitude, Adjustment and Reaction embodies the result of her original study and investigation under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge and belief, this study is the first of its kind and is in no way a reproduction of any other research work. Dr.LSarkar ^''^ Professor of History Department of History University of North Bengal Darje^ingy^A^iCst^^a^r Department of History University nfVi,rth Bengal Darjeeliny l\V Bj DECLARATION I do hereby declare that the thesis entitled MINOR POLITICAL PARTIES AND THE LANGUAGE OF POLITICS IN LATE COLONIAL BENGAL (l921- 1947); ATTITUDE, ADJUSTMENT AND REACTION being submitted to the University of North Bengal in partial fulfillment for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in History is an original piece of research work done by me and has not been published or submitted elsewhere for any other degree in full or part of it. -

NDA II 2019 Important Questions (Solution)

www.gradeup.co NDA II 2019 Important Questions (Solution) 1. Ans. D. * Sthanakvasi is a sect of Svetambara Jainism founded by merchant named Lavaji in 1653 AD. * The sthanakvasi do not believe in idol worship. As such they do not have temples but only sthankas, prayer halls, where they carry on their religious fasts, festivals. * This is because this sect believes that idol worship is not essential in the path of soul purification and attainment of nirvana/ moksha. 2. Ans. B. The tribes mentioned in the Rigveda are described as semi-nomadic pastoralists. During the successful in the early power-struggles between the various Aryan and non-Aryan tribes so that they continue to dominate in post-Rigvedic texts. 3. Ans. C. * Panini is known for his Sanskrit grammar, particularly for his formulation of the 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology, syntax and semantics in the grammar known eight chapters, the foundational text of the grammatical branch of the Vedanga, the auxiliary scholarly disciplines of the historical Vedic religion. * The Mahabhasya attributed to Patanjali, is a commentary on selected rules of Sanskrit grammar. * Kashika Vritti of Jayaditya is considered the "fourth great grammar" of Sanskrit, after Pāṇini himself (4th century BC), Patanjali's Mahabhasya (2nd century BC) and Bhartrhari's Vakyapadiya (6th century AD). 4. Ans. C. Hiuen Tsang (also Xuanzang, Hsuan Tsang) was the celebrated Chinese traveler who visited India in Ancient Times. 5. Ans. C. · Yaudheya as we know it were an ancient republican city state or tribe of traders and warriors. The name ‘Yudha’ itself means a proficient fighter. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

{PDF} the Sea and Poison: a Novel Ebook, Epub

THE SEA AND POISON: A NOVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Shusaku Endo, Michael Gallagher | 175 pages | 31 Mar 1993 | New Directions Publishing Corporation | 9780811211987 | English | New York, United States The Sea and Poison: A Novel PDF Book Select Parent Grandparent Teacher Kid at heart. Book is in Used-Good condition. All pages and cover are intact including the dust cover, if applicable. Sign Up. Despite the intrusive "barrier" of translation, Endo's novels have always provided me with valuable instruction in how to locate character. Publisher Direct via United States. Trade paperback. The book has been read but remains in clean condition. The limit to which the bronchial tubes may be cut before death occurs is to be ascertained. This topic is currently marked as "dormant"—the last message is more than 90 days old. Paperback or Softback. Why, he wants to know, does a Caribbean-born British writer consider Shusaku Endo to be a great personal influence upon his own work? MovieMars Books via United States. Mpn: Does Not Apply. And today, if we are to survive our 21st- century world, slippage, hybridity and change must be embraced and go unpunished. HippoBooks via United States. Page Count Seller Inventory GI3N Accessories such as CD, codes, toys, may not be included. It'll stay with me for a long time. Very minimal writing or notations in margins not affecting the text. I regarded the Britain that I grew up in during the 60s and 70s as inflexible and not readily open to change. And then Todo is that right? He nods, but is quick to clarify the situation. -

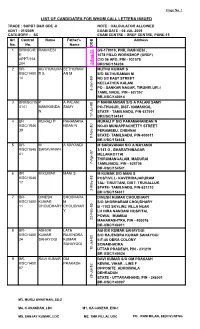

List of Candidates for Whom Call Letters Issued

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED TRADE : SUPDT B&R GDE -II NOTE : CALCULATOR ALLOWED ADVT - 01/2009 EXAM DATE - 06 JUL 2009 CATEGORY - SC EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 Srl Control Name Father's Address No. No. Name DOB 1 BRII/SC/R RAM KESI GS-179019, PNR, RAM KESI , E- 1078 FIELD WORKSHOP (GREF) APPT/154 C/O 56 APO, PIN - 931078 204 3-Aug-71 BRII/SC/154204 2 BR- MUTHUKUMA SETHURAM MUTHU KUMAR S II/SC/1400 R S AN M S/O SETHURAMAN M 14 NO 5/2 EAST STREET KEELATHEN KALAM PO - SANKAR NAGAR, TIRUNELUELI 8-Jan-80 TAMIL NADU, PIN - 627357 BR-II/SC/140014 3 BRII/SC/15 P A PALANI P MANIKANDAN S/O A PALANI SAMY 4141 MANIKANDA SAMY PO-THUSUR, DIST- NAMAKKAL N STATE - TAMILNADU, PIN-637001 17-Jul-88 BRII/SC/154141 4 BR MURALI P PARAMANA MURALI P S/O PARAMANANDAN N II/SC/1546 NDAN N NO-83 MUNIAPPACHETTY STREET 38 PERAMBEU, CHENNAI STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-600011 9-Nov-80 BR II/SC/154638 5 BR- M A MAYANDI M SARAVANAN S/O A MAYANDI II/SC/1545 SARAVANAN 3/143 G , BHARATHINAGAR 41 MELAKKOTTAI THIRUMANGALAM, MADURAI 7-Apr-87 TAMILNADU, PIN - 625706 BR-II/SC/154541 6 BR M KUMAR MANI S M KUMAR S/O MANI S II/SC/1546 POST/VILL- KAVERIRAJAPURAM 17 TAL- TIRUTTANI, DIST- TRUVALLUR STATE- TAMILNADU, PIN-631210 2-May-83 BR II/SC/154617 7 BR- DINESH SHOBHARA DINESH KUMAR CHOUDHARY II/SC/1400 KUMAR M S/O SHOBHARAM CHOUDHARY 11 CHOUDHARY CHOUDHAR B -1102 SKYLINE VILLA NEAR Y LH HIRA NANDANI HOSPITAL POWAI, MUMBAI 22-Feb-85 MAHARASHTRA, PIN - 400076 BR-II/SC/140011 8 BR- ASHOK LATE ASHOK KUMAR SAHAYOGI II/SC/1400 KUMAR RAJENDRA S/O RAJENDRA KUMAR SAHAYOGI 24 SAHAYOGI KUMAR 5-F-46 OBRA COLONY SAHAYOGI SONABHADRA 10-Jul-82 UTTAR PRADESH, PIN - 231219 BR-II/SC/140024 9 BR- RAVI KUMAR OM RAVI KUMAR S/O OM PRAKASH II/SC/1400 PRAKASH KEWAL VIHAR , LINE F 07 OPPOSITE ADHOIWALA DEHRADUN 28-Jul-82 STATE - UTTARAKHAND, PIN - 248001 BR-II/SC/140007 M3. -

Fazlul Huq, Peasant Politics and the Formation of the Krishak Praja Party (KPP)

2 Fazlul Huq, Peasant Politics and the Formation of the Krishak Praja Party (KPP) In all parts of India, the greater portion of the total population is, and always has been, dependent on the land for its existence and subsistence. During the colonial rule, this was absolutely true in the case of Bengal as a whole and particularly so of its eastern districts. In this connection, it should be mentioned here that the Muslim masses even greater number than the Hindus, were more concentrated in agriculture which is clearly been reflected in the Bengal Census of 1881: “………..while the husbandmen among the Hindus are only 49.28 per cent, the ratio among the Muslims is 62.81 per cent”.1 The picture was almost the same throughout the nineteenth century and continued till the first half of the twentieth century. In the different districts of Bengal, while the majority of the peasants were Muslims, the Hindus were mainly the landowning classes. The Census of 1901 shows that the Muslims formed a larger portion of agricultural population and they were mostly tenants rather than landlords. In every 10,000 Muslims, no less than 7,316 were cultivators, but in the case of the Hindus, the figure was 5,555 amongst the same number (i.e. 10,000) of Hindu population. But the proportion of landholders was only 170 in 10,000 in the case of Muslims as against 217 in the same number of Hindus.2 In the district of Bogra which was situated in the Rajshahi Division, the Muslims formed more than 80% of the total population. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Wednesday, 27th of January, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 27-01-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 27-01-2021 2 6 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 27-01-2021 3 7 HON'BLE JUSTICE MD. NIZAMUDDIN DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 27-01-2021 4 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 27-01-2021 5 23 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 12:50 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 27-01-2021 6 24 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 27-01-2021 7 36 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 27-01-2021 8 39 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 27-01-2021 9 56 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 238 On 27-01-2021 10 59 HON'BLE JUSTICE JAY SENGUPTA DB At 03:00 PM 36 On 27-01-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 67 SB - I At 02:00 PM 38 On 27-01-2021 12 HON'BLE JUSTICE ASHIS KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 70 SB - II At 10:45 AM 9 On 27-01-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 84 SB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 13 On 27-01-2021 14 88 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB At 03:00 PM 13 On 27-01-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 89 SB - IV At 10:45 AM 8 On 27-01-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 103 SB - V At 10:45 AM 26 On 27-01-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

Kazi Nazrul Islam

Classic Poetry Series Kazi Nazrul Islam - 265 poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: PoemHunter.Com - The World's Poetry Archive Kazi Nazrul Islam (24 May 1899 - 29 August 1976) Kazi Nazrul Islam was a Bengali poet, musician and revolutionary who pioneered poetic works espousing intense spiritual rebellion against fascism and oppression. His poetry and nationalist activism earned him the popular title of Bidrohi Kobi (Rebel Poet). Accomplishing a large body of acclaimed works through his life, Nazrul is officially recognised as the national poet of Bangladesh and commemorated in India. Born into a Muslim quazi (justice) family in India, Nazrul received religious education and worked as a muezzin at a local mosque. He learned of poetry, drama, and literature while working with theatrical groups. After serving in the British Indian Army, Nazrul established himself as a journalist in Kolkata (then Calcutta). He assailed the British Raj in India and preached revolution through his poetic works, such as 'Bidrohi' ('The Rebel') and 'Bhangar Gaan' ('The Song of Destruction'), as well as his publication 'Dhumketu' ('The Comet'). His impassioned activism in the Indian independence movement often led to his imprisonment by British authorities. While in prison, Nazrul wrote the 'Rajbandir Jabanbandi' ('Deposition of a Political Prisoner'). Exploring the life and conditions of the downtrodden masses of India, Nazrul worked for their emancipation. Nazrul's writings explore themes such as love, freedom, and revolution; he opposed all bigotry, including religious and gender. Throughout his career, Nazrul wrote short stories, novels, and essays but is best-known for his poems, in which he pioneered new forms such as Bengali ghazals. -

100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan

100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan The Nippon Foundation Copyright © 2008 All rights reserved The Nippon Foundation The Nippon Zaidan Building 1-2-2 Akasaka, Minato-ku Tokyo 107-8404, Japan Telephone +81-3-6229-5111 / Fax +81-3-6229-5110 Cover design and layout: Eiko Nishida (cooltiger ltd.) February 2010 Printed in Japan 100 Books for Understanding Contemporary Japan Foreword 7 On the Selection Process 9 Program Committee 10 Politics / International Relations The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa / Yukichi Fukuzawa 12 Broadcasting Politics in Japan: NHK and Television News / Ellis S. Krauss 13 Constructing Civil Society in Japan: Voices of Environmental Movements / 14 Koichi Hasegawa Cultural Norms and National Security: Police and Military in Postwar Japan / 15 Peter J. Katzenstein A Discourse By Three Drunkards on Government / Nakae Chomin 16 Governing Japan: Divided Politics in a Major Economy / J.A.A. Stockwin 17 The Iwakura Mission in America and Europe: A New Assessment / 18 Ian Nish (ed.) Japan Remodeled: How Government and Industry are Reforming 19 Japanese Capitalism / Steven K. Vogel Japan Rising: The Resurgence of Japanese Power and Purpose / 20 Kenneth B. Pyle Japanese Foreign Policy at the Crossroads / Yutaka Kawashima 21 Japan’s Love-Hate Relationship with the West / Sukehiro Hirakawa 22 Japan’s Quest for a Permanent Security Council Seat / Reinhard Drifte 23 The Logic of Japanese Politics / Gerald L. Curtis 24 Machiavelli’s Children: Leaders and Their Legacies in Italy and Japan / 25 Richard J. Samuels Media and Politics in Japan / Susan J. Pharr & Ellis S. Krauss (eds.) 26 Network Power: Japan and Asia / Peter Katzenstein & Takashi Shiraishi (eds.) 27 Regime Shift: Comparative Dynamics of the Japanese Political Economy / 28 T. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Monday, 26th of July, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL , CHIEF 1 On 26-07-2021 1 JUSTICE (ACTING) 1 DB-I At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJARSHI BHARADWAJ HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 26-07-2021 2 4 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 28 On 26-07-2021 3 7 HON'BLE JUSTICE BIBEK CHAUDHURI DB-III At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 16 On 26-07-2021 4 55 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - V At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 26-07-2021 5 62 HON'BLE JUSTICE JAY SENGUPTA DB-VI At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 30 On 26-07-2021 6 71 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB-VII At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 26-07-2021 7 77 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB - VIII At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 32 On 26-07-2021 8 89 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - IX At 11:00 AM 8 On 26-07-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE DEBANGSU BASAK 119 SB II At 11:00 AM 42 On 26-07-2021 10 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 150 SB - III At 11:00 AM 13 On 26-07-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 154 SB - IV At 11:00 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI 7 On 26-07-2021 12 188 BHATTACHARYYA SB - V At 11:00 AM 26 On 26-07-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHEKHAR B. -

1 a Film by Martin Scorsese Opens in Cinemas

A film by Martin Scorsese Opens in cinemas nationally on FEBRUARY 16, 2017 PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films Australia / Amy Burgess +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and key art poster available to via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/silence 1 PRODUCTION INFORMATION Martin Scorsese’s Silence, the Academy Award winning director’s long anticipated film about faith and religion, tells the story of two 17th century Portuguese missionaries who undertake a perilous journey to Japan to search for their missing mentor, Father Christavao Ferreira, and to spread the gospel of Christianity. Scorsese directs Silence from a screenplay he wrote with Jay Cocks. The film, based on Shusaku Endo’s 1966 award-winning novel, examines the spiritual and religious question of God’s silence in the face of human suffering. Martin Scorsese and Emma Koskoff and Irwin Winkler produce alongside Randall Emmett, Barbara De Fina, Gastón Pavlovich, and Vittorio Cecchi Gori with executive producers Dale A. Brown, Matthew J. Malek, Manu Gargi, Ken Kao, Dan Kao, Niels Juul, Chad A. Verdi, Gianni Nunnari, Len Blavatnik and Aviv Giladi. Silence stars Andrew Garfield (The Amazing Spider Man, Hacksaw Ridge), Adam Driver (Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Paterson) and Liam Neeson (Schindler’s List, Taken). The film follows the young missionaries, Father Sebastian Rodrigues (Garfield) and Father Francisco Garupe (Driver) as they search for their missing teacher and mentor and minister to the Christian villagers they encounter who are forced to worship in secret. At that time in Japan, feudal lords and ruling Samurai were determined to eradicate Christianity in their midst; Christians were persecuted and tortured, forced to apostatize, that is, renounce their faith or face a prolonged and agonizing death. -

Mimetic Desire, Institutions, and Shūsaku Endō's Loving Gaze On

Persecutor’s Remorse: Mimetic Desire, Institutions, and Shūsaku Endō’s Loving Gaze on Persecutors A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Jirayu Smitthimedhin 1 May 2019 Smitthimedhin 2 Liberty University College of Arts and Sciences Master of Arts in English Student Name: Jirayu Smitthimedhin ______________________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair: Dr. Stephen Bell Date ______________________________________________________________________________ First Reader: Dr. Karen Swallow Prior Date ______________________________________________________________________________ Second Reader: Professor Nicholas Olson Date Smitthimedhin 3 “Man is a splendid and beautiful being and, at the same time, man is a terrible being as we recognised in Auschwitz —God knows well this monstrous dual quality of man.” -Shūsaku Endō “We are of the same spiritual race… and from childhood we were accustomed to examine our hearts, to bring light to bear on our thoughts, our desires, our acts, our omissions. We know that evil is an immense fund of capital shared among all people, and that there is nothing in the criminal heart, no matter how horrible, whose germ is not also to be found in our own hearts.” - François Mauriac “The principal source of violence between human beings is mimetic rivalry, the rivalry resulting from imitation of a model who becomes a rival or of a rival who becomes a model” (I See Satan, 2). - René Girard “Ordinary men are usually part of a social and moral network that helps them maintain their humanity toward others and prevents them from becoming involved in inhuman acts. In order to socialize them into becoming murderers, they have to be insulated from their original social network and an alternative network has to be created for the potential killers, composed of men like themselves, led by a genocidal authority.