2 Subst. Crim. L. § 13.2 (2D Ed.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Substitution Model

The Substitution Model Nate Foster Spring 2018 Review Previously in 3110: simple interpreter for expression language • abstract syntax tree (AST) • evaluation based on single steps • parser and lexer (in lab) Today: • Formal syntax: BNF • Formal dynamic semantics: small-step, substitution model • Formal static semantics Substitution (* [subst e v x] is e{v/x}, that is, * [e] with [v] substituted for [x]. *) let rec subst e v x = match e with | Var y -> if x=y then v else e | Int n -> Int n | Add(el,er) -> Add(subst el v x, subst er v x) | Let(y,ebind,ebody) -> let ebind' = subst ebind v x in if x=y then Let(y, ebind', ebody) else Let(y, ebind', subst ebody v x) Step let rec step = function | Int n -> failwith "Does not step" | Add(Int n1, Int n2) -> Int (n1 + n2) | Add(Int n1, e2) -> Add (Int n1, step e2) | Add(e1, e2) -> Add (step e1, e2) | Var _ -> failwith "Unbound variable" | Let(x, Int n, e2) -> subst e2 (Int n) x | Let(x, e1, e2) -> Let (x, step e1, e2) FORMAL SYNTAX Abstract syntax of expression lang. e ::= x | i | e1+e2 | let x = e1 in e2 e, x, i: meta-variables that stand for pieces of syntax • e: expressions • x: program variables, aka identifiers • i: integer constants, aka literals ::= and | are meta-syntax: used to describe syntax of language notation is called Backus-Naur Form (BNF) from its use by Backus and Naur in their definition of Algol-60 Backus and Naur John Backus (1924-2007) ACM Turing Award Winner 1977 “For profound, influential, and lasting contributions to the design of practical high-level programming systems” Peter Naur (1928-2016) ACM Turing Award Winner 2005 “For fundamental contributions to programming language design” Abstract syntax of expr. -

More General Naming a Substitution Model for Bindex Table of Contents

Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model More general naming A substitution model for Bindex Theory of Programming Languages Computer Science Department Wellesley College Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Table of contents Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Substitution Renaming is a special case of a more general program form of • program manipulation called substitution. In substitution, all free occurrences of a variable name are • replaced by a given expression. For example, substituting (+ b c) for a in (* a a) yields (* (+ b c) (+ b c)). If we view expressions as trees, then substitution replaces • certain leaves (those with the specified name) by new subtrees. Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Substituting trees for trees For example, substituting the tree on the left for the one on the right yields the tree Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Preserving the “naming wiring structure” of expressions As in renaming, substitution must avoid variable capture to preserve the “naming wiring structure” of expressions. In particular, when substituting for a variable I, we will never • perform substitutions on I within the scope of a bind expression that binds I. For example, substituting (+ b c) for a in • (bind a (* a a) (- a 3)) yields: (bind a (* (+ b c) (+ b c)) (- a 3)) Here the free occurrences of a have been replaced by (+ b • c), but the bound occurrences have not been changed. Substitution subst Bindex subst model Bindex environment model Renaming to avoid variable capture Furthermore, bind-bound variables may be renamed to avoid variable capture • with free variables in the expression being substituted for the variable. -

List of MS-DOS Commands - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 25

List of MS-DOS commands - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 25 List of MS-DOS commands From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In the personal computer operating systems MS -DOS and PC DOS, a number of standard system commands were provided for common Contents tasks such as listing files on a disk or moving files. Some commands were built-in to the command interpreter, others existed as transient ■ 1 Resident and transient commands commands loaded into memory when required. ■ 2 Command line arguments Over the several generations of MS-DOS, ■ 3 Windows command prompt commands were added for the additional ■ 4 Commands functions of the operating system. In the current ■ 4.1 @ Microsoft Windows operating system a text- ■ 4.2 : mode command prompt window can still be ■ 4.3 ; used. Some DOS commands carry out functions ■ 4.4 /* equivalent to those in a UNIX system but ■ 4.5 ( ) always with differences in details of the ■ 4.6 append function. ■ 4.7 assign ■ 4.8 attrib ■ 4.9 backup and restore Resident and transient ■ 4.10 BASIC and BASICA commands ■ 4.11 call ■ 4.12 cd or chdir ■ 4.13 chcp The command interpreter for MS-DOS runs ■ 4.14 chkdsk when no application programs are running. ■ 4.15 choice When an application exits, if the command ■ 4.16 cls interpreter in memory was overwritten, MS- ■ 4.17 copy DOS will re-load it from disk. The command ■ 4.18 ctty interpreter is usually stored in a file called ■ 4.19 defrag "COMMAND.COM". Some commands are ■ 4.20 del or erase internal and built-into COMMAND.COM, ■ 4.21 deltree others are stored on disk in the same way as ■ 4.22 dir application programs. -

Ch 7 Using ATTRIB, SUBST, XCOPY, DOSKEY, and the Text Editor

Using ATTRIB, SUBST, XCOPY, DOSKEY, and the Text Editor Ch 7 1 Overview The purpose and function of file attributes will be explained. Ch 7 2 Overview Utility commands and programs will be used to manipulate files and subdirectories to make tasks at the command line easier to do. Ch 7 3 Overview This chapter will focus on the following commands and programs: ATTRIB XCOPY DOSKEY EDIT Ch 7 4 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command Root directory keeps track of information about every file on a disk. Ch 7 5 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command Each file in the directory has attributes. Ch 7 6 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command Attributes represented by single letter: S - System attribute H - Hidden attribute R - Read-only attribute A - Archive attribute Ch 7 7 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command NTFS file system: Has other attributes At command line only attributes can change with ATTRIB command are S, H, R, and A Ch 7 8 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command ATTRIB command: Used to manipulate file attributes Ch 7 9 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command ATTRIB command syntax: ATTRIB [+R | -R] [+A | -A] [+S | -S] [+H | -H] [[drive:] [path] filename] [/S [/D]] Ch 7 10 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command Attributes most useful to set and unset: R - Read-only H - Hidden Ch 7 11 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command The A attribute (archive bit) signals file has not been backed up. Ch 7 12 File Attributes and the ATTRIB Command XCOPY command can read the archive bit. -

Hitek Software Help File Version 6

Version 6.x Language English Contents ● Introduction ● Purchase Information ● Getting Started ● Basics ● Tasks ● Variables ● Tutorials ● NT Service Module ● Command Line Module ● User Case Studies ● Performance and Reliability Testing Introduction This software is designed to automatically execute tasks. The software can be run on windows, macintosh, linux, and on other operating systems. Tasks can be scheduled on a daily, weekly, monthly, or hourly basis. Tasks can also be scheduled by the minute, or second. Tasks include local and internet applications, file download and monitoring. This software is available on a 30 day free trial basis. You can test it during this period. After 30 days, the software expires, and you will need to register the software. If you do not want to use the software, you can uninstall it from your computer. The uninstall procedure will depend on the operating system. Typically, an uninstall program is also loaded onto your computer. Please see your help file for uninstall instructions. If you need to use this software for more than 30 days, please register it. You can purchase online by credit card, check, money order, or purchase order. Multiple copy discounts, and site licenses are available. See the Hitek Software web page, at "http://www.hiteksoftware.com" for details. Purchase Information | When you purchase this software, you will receive registration instructions via email. Follow the registration instructions very carefully, to receive the registration key. The registration key is required to unlock the software. Please visit our web site at 'http://www.hiteksoftware.com', for latest purchasing details and pricing information. You can purchase, using one of the following methods: 1. -

Datalight ROM-DOS User's Guide

Datalight ROM-DOS User’s Guide Created: April 2005 Datalight ROM-DOS User’s Guide Copyright © 1999-2005 by Datalight, Inc . Portions copyright © GpvNO 2005 All Rights Reserved. Datalight, Inc. assumes no liability for the use or misuse of this software. Liability for any warranties implied or stated is limited to the original purchaser only and to the recording medium (disk) only, not the information encoded on it. U.S. Government Restricted Rights. Use, duplication, reproduction, or transfer of this commercial product and accompanying documentation is restricted in accordance with FAR 12.212 and DFARS 227.7202 and by a license agreement. THE SOFTWARE DESCRIBED HEREIN, TOGETHER WITH THIS DOCUMENT, ARE FURNISHED UNDER A SEPARATE SOFTWARE OEM LICENSE AGREEMENT AND MAY BE USED OR COPIED ONLY IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF THAT AGREEMENT. Datalight and ROM-DOS are registered trademarks of Datalight, Inc. FlashFX ® is a trademark of Datalight, Inc. All other product names are trademarks of their respective holders. Part Number: 3010-0200-0716 Contents Chapter 1, ROM-DOS Introduction..............................................................................................1 About ROM-DOS ......................................................................................................................1 Conventions Used in this Manual .......................................................................................1 Terminology Used in this Manual ......................................................................................1 -

Microsoft® MS-DOS® 3.3 Reference

Microsoft® MS-DOS® 3.3 Reference HP 9000 Series 300/800 Computers HP Part Number 98870-90050 Flin- HEWLETT ~~ PACKARD Hewlett-Packard Company 3404 East Harmony Road, Fort Collins, Colorado 80525 NOTICE The information contained In this document is subject to change without notice HEWLETT-PACKARD MAKES NO WARRANTY OF ANY KIND WITH REGARD TO THIS MANUAL. INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Hewlett-Packard shall not be liable for errors contained herein or direct. indirect. special, incidental or consequential damages in connection with the furnishing, performance, or use of this material WARRANTY A copy of the specific warranty terms applicable to your Hewlett-Packard product and replacement parts can be obtained from your local Sales and Service Office MS -DOS is a US registered trademark of Microsoft, Incorporated. LOTUS and 1-2-3 are registered trademarks of LOTUS Development Corporation. Copynght 1988. 1989 Hewlett-Packard Company This document contains proprietary information which is protected by copyright. All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be photocopied. reproduced or translated to another language without the prior written consent of Hewlett-Packard Company. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. Restricted Rights Legend Use. duplication or disclosure by the Government is subject to restrictions as set forth in paragraph (b)(3)(B) of the Rights in Technical Data and Software clause in DAR 7-104.9(a). Use of this manual and flexible disc(s) or tape cartridge(s) supplied for this pack is restricted to this product only. -

OS Commands and Scripts Steven L

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2018 ITS 165.01: OS Commands and Scripts Steven L. Stiff University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Recommended Citation Stiff, Steven L., "ITS 165.01: OS Commands and Scripts" (2018). Syllabi. 8421. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/8421 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ITS 165-01 OS COMMANDS AND SCRIPTS � COURSE SYLLABUS Missoula College UM Department of Applied Computing and Engineering Technology Course Number and Title .........ITS 165 OS Commands & Scripts Section ......................................01 (CRN 73284) Term ..........................................Fall 2018 Semester Credits ......................3 Prerequisites .............................M 90 or consent of instructor Faculty Contact Information Faculty Office Office Hours Steven (Steve) L. Stiff MC322 MWF, 11:30 AM – 12:30 PM Phone: (406) 243-7913 or by appointment Email: [email protected] Class Meeting Times and Final Lecture Day, Time, and Location ................. MW, 2:00pm – 2:50pm, MC122 Lab Day, Time, and Location ....................... T, 12:30 PM – 2:00 PM, MC025 Final Exam Date, Time, and Location .......... T, 12/11/18, 1:10pm – 3:10pm, MC122 Course Description Emphasis on the use of the Windows 7 and Windows 10 operating system (OS) command line interface, and includes the creation and execution of script files in Windows environment. -

Windirstat - Directory Statistics Copyright (C) 2003-2005 Bernhard Seifert

WinDirStat - Directory Statistics Copyright (c) 2003-2005 Bernhard Seifert. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back- Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Shows where all your disk space has gone, and helps you clean it up. You know the problem: The hard disk is almost full, and you don't know, where the big files actually are lying, which occupy all the space. They may well be hidden in sub-sub-directories. To find out this by means of the Windows Explorer, is tiring: you would have to expand and collapse directories over and over or view the "Properties" of the directories, which always count just the size of a single subtree. It's hard to form a mental image of the hard disk usage in this way. This is where WinDirStat helps. On start up WinDirStat opens the Select Drives Dialog. Press the OK button. Then WinDirStat reads in the whole directory tree once (this can last some minutes depending on the hard disk size) and then presents it in three useful views: WinDirStat Directory List Extension List Treemap The views are coupled with each other. You can clean up the hard disks with several Cleanups. The views and the User Defined Cleanups can be configured according to your personal needs. -

Advanced Bash-Scripting Guide

Advanced Bash−Scripting Guide An in−depth exploration of the art of shell scripting Mendel Cooper <[email protected]> 2.4 25 January 2004 Revision History Revision 2.1 14 September 2003 Revised by: mc 'HUCKLEBERRY' release: bugfixes and more material. Revision 2.2 31 October 2003 Revised by: mc 'CRANBERRY' release: Major update. Revision 2.3 03 January 2004 Revised by: mc 'STRAWBERRY' release: Major update. Revision 2.4 25 January 2004 Revised by: mc 'MUSKMELON' release: Bugfixes. This tutorial assumes no previous knowledge of scripting or programming, but progresses rapidly toward an intermediate/advanced level of instruction . all the while sneaking in little snippets of UNIX® wisdom and lore. It serves as a textbook, a manual for self−study, and a reference and source of knowledge on shell scripting techniques. The exercises and heavily−commented examples invite active reader participation, under the premise that the only way to really learn scripting is to write scripts. This book is suitable for classroom use as a general introduction to programming concepts. The latest update of this document, as an archived, bzip2−ed "tarball" including both the SGML source and rendered HTML, may be downloaded from the author's home site. See the change log for a revision history. Dedication For Anita, the source of all the magic Advanced Bash−Scripting Guide Table of Contents Chapter 1. Why Shell Programming?...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 2. Starting -

Microsoft Windows XP - Command-Line Reference A-Z

www.GetPedia.com *More than 150,000 articles in the search database *Learn how almost everything works Microsoft Windows XP - Command-line reference A-Z Windows XP Professional Product Documentation > Performance and maintenance Command-line reference A-Z To find information about a command, on the A-Z button menu at the top of this page, click the letter that the command starts with, and then click the command name. In addition to the tools installed with Windows XP, there are over 40 support tools included on the Windows XP CD. You can use these tools to diagnose and resolve computer problems. For more information about these support tools, see Windows Support Tools For information about installing support tools, see Install Windows Support Tools For more information about changes to the functionality of MS-DOS commands, new command-line tools, command shell functionality, configuring the command prompt, and automating commmand-line tasks, see Command-line reference Some command-line tools require the user to have administrator-level privileges on source and/or target computers. Command-line tools must be run at the prompt of the Cmd.exe command interpreter. To open Command Prompt, click Start, click Run, type cmd, and then click OK. To view help at the command-line, at the command prompt, type the following: CommandName /? A Arp Assoc At Atmadm Attrib Top of page B Batch files http://www.microsoft.com/resources/documentation/windows/xp/all/proddocs/en-us/ntcmds.mspx?pf=true (1 of 11)5/22/2004 10:58:52 PM Microsoft Windows XP - Command-line -

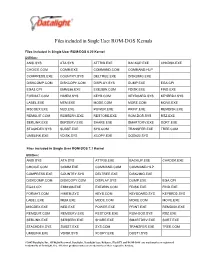

Files Included in Single User ROM-DOS Kernals

Files included in Single User ROM-DOS Kernals Files included in Single User ROM-DOS 6.22 Kernel Utilities: ANSI.SYS ATA.SYS ATTRIB.EXE BACKUP.EXE CHKDSK.EXE CHOICE.COM COMM.EXE COMMAND.COM COMMAND.HLP COMPRESS.EXE COUNTRY.SYS DELTREE.EXE DISK2IMG.EXE DISKCOMP.COM DISKCOPY.COM DISPLAY.SYS DUMP.EXE EGA.CPI EGA3.CPI EMM386.EXE EXE2BIN.COM FDISK.EXE FIND.EXE FORMAT.COM HIMEM.SYS KEYB.COM KEYBOARD.SYS KEYBRD2.SYS LABEL.EXE MEM.EXE MODE.COM MORE.COM MOVE.EXE MSCDEX.EXE NED.EXE POWER.EXE PRINT.EXE REMDISK.EXE REMQUIT.COM REMSERV.EXE RESTORE.EXE ROM-DOS.SYS RSZ.EXE SERLINK.EXE SERSERV.EXE SHARE.EXE SMARTDRV.EXE SORT.EXE STACKDEV.SYS SUBST.EXE SYS.COM TRANSFER.EXE TREE.COM UMBLINK.EXE VDISK.SYS XCOPY.EXE DOS622.SYS Files included in Single User ROM-DOS 7.1 Kernel Utilities: ANSI.SYS ATA.SYS ATTRIB.EXE BACKUP.EXE CHKDSK.EXE CHOICE.COM COMM.EXE COMMAND.COM COMMAND.HLP COMPRESS.EXE COUNTRY.SYS DELTREE.EXE DISK2IMG.EXE DISKCOMP.COM DISKCOPY.COM DISPLAY.SYS DUMP.EXE EGA.CPI EGA3.CPI EMM386.EXE EXE2BIN.COM FDISK.EXE FIND.EXE FORMAT.COM HIMEM.SYS KEYB.COM KEYBOARD.SYS KEYBRD2.SYS LABEL.EXE MEM.EXE MODE.COM MORE.COM MOVE.EXE MSCDEX.EXE NED.EXE POWER.EXE PRINT.EXE REMDISK.EXE REMQUIT.COM REMSERV.EXE RESTORE.EXE ROM-DOS.SYS RSZ.EXE SERLINK.EXE SERSERV.EXE SHARE.EXE SMARTDRV.EXE SORT.EXE STACKDEV.SYS SUBST.EXE SYS.COM TRANSFER.EXE TREE.COM UMBLINK.EXE VDISK.SYS XCOPY.EXE DOS71.SYS ©2005 Datalight, Inc.