Iconic Projects As Catalysts for Brownfield Redevelopments 106 200 M Appendix I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I

Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 Rotterdam TU1206-WG1-013 TU1206 COST Sub-Urban WG1 Report I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Sub-Urban COST is supported by the EU Framework Programme Horizon 2020 COST TU1206 Sub-Urban Report TU1206-WG1-013 Published March 2016 Authors: I. van Campenhout, K de Vette, J. Schokker & M van der Meulen Editors: Ola M. Sæther and Achim A. Beylich (NGU) Layout: Guri V. Ganerød (NGU) COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a pan-European intergovernmental framework. Its mission is to enable break-through scientific and technological developments leading to new concepts and products and thereby contribute to strengthening Europe’s research and innovation capacities. It allows researchers, engineers and scholars to jointly develop their own ideas and take new initiatives across all fields of science and technology, while promoting multi- and interdisciplinary approaches. COST aims at fostering a better integration of less research intensive countries to the knowledge hubs of the European Research Area. The COST Association, an International not-for-profit Association under Belgian Law, integrates all management, governing and administrative functions necessary for the operation of the framework. The COST Association has currently 36 Member Countries. www.cost.eu www.sub-urban.eu www.cost.eu Rotterdam between Cables and Carboniferous City development and its subsurface 04-07-2016 Contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................................5 -

Despite the Current Recession in the Dutch Building Industry, Construction

Rotterdam, CENTRAAL STATION (****– 2013) Architect: Team CS met Maarten Struijs 1 Address: Stationsplein 1 ZEECONTAINER RESTAURANT (2005) 15 Architect: Bijvoet architectuur & Stadsontwerp large and small Address: Loods Celebes 101 HOGE HEREN (2005) RED APPLE (2009) Architect: Wiel Arets Architects Address: Gedempte Zalmhaven 179 Despite the current recession in the Dutch building industry, Architect: KCAP Architects & Planners 10 construction – of both the large-scale high-rise projects typical 6 Address: Wijnbrugstraat 200 of this city and more modest ‘infill’ architecture – continues apace in Rotterdam. ACHTERHAVEN (2011) THE NETHERLANDS — TEXT: Emiel Lamers, photography: Sonia Mangiapane, Illustration: Loulou&Tummie Architect: Studio Sputnik 16 Address: Achterhaven otterdam is one of the few old cities line. Since the construction of the Erasmus No one arriving in Rotterdam by train can is regarded as a monument of the post-war n der Hoek in Europe characterized by massive Bridge in 1996, the centre has expanded miss the massive reconstruction of Centraal reconstruction of the city. If all goes according A rd v KUNSTHAL (1992) high-rise in the centre of the city. In across the river to the poorer, southern part of Station (1). The original station hall de- to plan, it will be integrated with the new mu- A R All Architect: Rem Koolhaas, Fumi Hoshino OMA SCHIEBLOCK (2011) one night of heavy bombing on 14 May 1940, the city where two new districts, Kop van Zuid signed by Sybold van Ravesteyn in 1957, has nicipal offices (4), scheduled to open here in Address: Westzeedijk 341 CULTUURCENTRUM WORM (2011) 11 at the beginning of World War II, Rotterdam and Wilhelminapier, now boast some impres- made way for a much more spacious, raked March 2015. -

Handelingsperspectief Wijk Tarwewijk

Handelingsperspectief wijk Tarwewijk Maart 2013 Katendrechtse Lagendijk creatief allée bedrijven eigen buurtjes jong kinderrijk groen spelen park drukke niet-westers rande n luwe zwak binnen- drukke imago werelden randen starterswijk druk ke ran den “Tarwewijk: drukke randen en luwe binnenwerelden.” Maassilo zicht op Kop van zuid Buitenruimte Verschoorstraat Tarwebuurt, zicht richting Maashaven Karakteristiek Wonen én werken in de Tarwewijk spelen. De kwaliteiten van de luwe woongebieden die de In de Tarwewijk wonen ruim 12.000 mensen. Vergeleken met Tarwewijk biedt, zijn voor velen (nog) onbekend. de andere stadswijken op Zuid is de bevolking er jong, kent ze een hoog aandeel niet westerse allochtonen en is ze zeer Vestigings- versus doorgangsmentaliteit kinderrijk. Op het eerste gezicht lijkt de Tarwewijk vooral een In de Tarwewijk staan ruim 5.800 woningen. Het overgrote woonbuurt, toch is er ook een behoorlijke hoeveelheid econo- deel is gestapelde woningbouw, slechts 8% bestaat uit mische functies te vinden. Soms zichtbaar aan de randen van eengezinswoningen. Toch is dat niet bepalend voor het beeld de wijk, zoals aan de Brielselaan met de Creative Factory, of in van de Tarwewijk. De gestapelde woningen bevinden zich het zuiden langs de Pleinweg, soms minder opvallend gecom- in de vele randen en in de Mijnkintbuurt. Ongeveer 30% van bineerd met het wonen zoals de ‘huiskamereconomie’ in de de woningvoorraad is eigendom van corporaties, eenzelfde Bas Jungeriusstraat. De Tarwewijk is binnen Rotterdam de 4e aandeel eigenaar bewoners, de rest is particuliere verhuur. De wijk met het grootste aantal startende bedrijven. Vaak hebben wijk kent een probleem door de botsing van mentaliteiten: de het wonen en het werken echter niets met elkaar te maken, het vestigings- versus de doorgangsmentaliteit, die te maken heeft zijn gescheiden werelden. -

Strategic Development Plan

Uptown Neighborhood Strategic Development Plan Prepared by: In coordination with:: COUNTY E c . o p n r o o m C ic nt Adopted: March 3, 2015 Developme Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Uptown Redevelopment Vision ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Existing Conditions Analysis ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Assets & Opportunities ............................................................................................................................................................ 14 Recommendations for Revitalization .................................................................................................................................... 20 Implementation ......................................................................................................................................................................... 33 Prepared by Vandewalle & Associates, Madison and Milwaukee, Wisconsin In coordination with the Uptown Strategic Development Plan Project Management Team*: • Mayor John Dickert, City of Racine • State Representative Cory Mason • Chris Eperjesy, Twin Disc • Brett Neylan, SC Johnson & Son • Tom Friedel, -

TOEGANG TOT M4H Naar Een Sociaal Raamwerk Voor Een Nieuwe Stadswijk

TOEGANG TOT M4H Naar een Sociaal Raamwerk voor een nieuwe stadswijk David ter Avest praktijkgericht onderzoek Auteur: David ter Avest Met medewerking van: Gert-Joost Peek Kees Stam Omslagfoto: Michaël Meijer Hogeschool Rotterdam Kenniscentrum Duurzame HavenStad Rotterdam, maart 2021 Alles uit deze uitgave mag, mits met bronvermelding, worden vermenigvuldigd en openbaar gemaakt Te downloaden via www.hogeschoolrotterdam.nl/onderzoek/ INHOUD VOORWOORD 5 0 INLEIDING 7 1 DE STAD EN DE HAVEN 8 1.1 Bouwen voor de haven 1.2 Waar stad en haven elkaar ontmoeten 2 DE UITVINDING VAN M4H 10 2.1 Grote dromen aan de Maas 2.2 Innovatie als constante 2.3 M4H als merk 2.4 Framing, nieuwe namen en afkortingen 3 TOEGANG TOT M4H 15 3.1 Een coöperatieve gebiedsontwikkeling 3.2 Sterke gemeenschappen en vitale netwerken 3.3 Maatschappelijk vastgoed in het nauw 4 WONEN IN M4H 20 4.1 Woonwijk in de maak 4.2 Enclavevorming voor ‘balans in de stad’ 4.3 Mathenesse aan de Maas 5 WERKEN IN M4H 23 5.1 Mismatch of kansrijk 5.2 Beloftevolle initiatieven voor kwetsbare verbindingen 5.3 De toekomstwaarde van onderwijs 6 RECREËREN IN M4H 27 6.1 Publieke voorzieningen gezocht 6.2 Recreatief water 6.3 Toegang gratis 7 NIEUWE WAARDEN VOOR EEN NIEUWE STADSWIJK 30 7.1 Waardengedreven stedelijke ontwikkeling 7.2 De capability approach 8 ACHT PRINCIPES VOOR EEN SOCIAAL RAAMWERK 32 EINDNOTEN 34 BRONNENLIJST 35 ILLUSTRATIES 41 VERANTWOORDING 42 OVER DE AUTEUR 42 VOORWOORD In dit onderzoeksessay onderbouwt docentonderzoeker David ter Avest de noodzaak van een Sociaal Raamwerk in aanvulling op het Ruimtelijk Raamwerk voor de gebiedsontwikkeling van Merwe-Vierha- vens, kortweg M4H. -

The Erasmus Bridge, a Moving Success Story

The Erasmus Bridge: Success factors according to those involved in the project Mig de Jong, TU Delft, [email protected] Jan Anne Annema, TU Delft, [email protected] Abstract This paper describes a case study of a successful major transport infrastructure project. There is relatively much literature on unsuccessful infrastructure projects and the subsequent lessons learned. In contrast there is hardly any literature on successful infrastructure projects. This paper wants to contribute in filling this scientific gap. The case is the Erasmus bridge in the Dutch city of Rotterdam which connects the banks of the Meuse River. This bridge is a success story for three reasons. The first two reason for success are that the bridge was built on time and within budget. The bridge cost about 163 million euro (1996 prices), with a budget of 165 million (1991 prices), and was opened on the precise date as planned. Its main goal was not to solve a traffic problem, or to expand the existing network. One of the main reasons for constructing is that the bridge should function as a landmark, and that is the third reason for success: the bridge has indeed become a trade mark for the city of Rotterdam. Based on interviews with people involved in the project, the main reason for success appears to be the culture of realistic estimating at the municipality of Rotterdam: an estimation culture that was aimed to be as accurate as possible. Two elements are crucial, as the interviewees have explained: a refusal to make lower estimations in order to help getting the required funds from local or national government and the ability to make very accurate cost estimations. -

Social Behavior in an Urban Context

VU Research Portal Some years of communities that care Jonkman, H.B. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Jonkman, H. B. (2012). Some years of communities that care: Learning from a social experiment. Euro-mail. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 SOME YEARS OF COMMUNITIES THAT CARE Part II: RESEARCH Solution ‘I am stubborn and in this stubbornness I give as wax so only I can print the world’ Tadeusz Rózewicz 90 Part II: RESEARCH / 91 n contrast to individual phenomena like intelligence and depression, the measurement of social phenomena and constructs like social economic status or social capital is in its infancy, and the situation is even worse for ecological constructs like communities, schools, and workplaces. -

Brownfield Association

Doing the Deal, Before the Deal Does You! About the National Brownfield Association Non-profit member-based educational organization for Brownfield professionals Network for exchanging ideas, experiences, and information Property Owners, Developers/Investors, Transaction Support Professionals Government Information, Education, and Events STAMP (Site Technical Assistance for Municipal Project) Building Sustainable Communities Workshop series The Big Deal October 3-4 Chicago IL Leadership BOD Advisory Board Chapters Sponsorship Association Events Newsletter Membership Group Individual Program Agenda 10:15- 12:15pm Workshop Goals/Overview of Tri-State Brownfield Programs John Means, WA Department of Ecology About the Brownfield Market Property Valuation Robert Colangelo, NBA Brownfield Risks and Solutions Robert Colangelo, National Brownfield Association Frank Chmelik, Chmelik, Sitkin & Davies 12:15 – 1:00 Lunch Public financing and Incentives to Stimulate Site Reuse Mike Stringer, Maul Foster & Alongi, Inc. Case Study: Boise Cascade Mill, Yakima Brad Hill, Principal Cascade Mill Properties, LLC Structuring the Transaction Robert Colangelo, NBA 3:00-4:30pm Role Playing Exercise Jim Darling, Maul Foster & Alongi, Inc. Robert Colangelo, NBA Presenters Robert Colangelo, National Brownfield Association Frank Chmelik, Chmelik, Sitkin & Davies Brad Hill, Principal Cascade Mill Properties, LLC Jim Darling, Maul Foster & Alongi, Inc. Mike Stringer, Maul Foster & Alongi, Inc. Workshop Goals Overview of Tri-State Brownfield Programs John Means, WA Department of Ecology About the Brownfield Market Robert Colangelo, NBA Publications Brownfield News. Founder and Publisher, Robert V. Colangelo, Environomics Communications, Inc. Chicago: Feb. 1997- Dec. 2008: Vol. 1-12. Szymeco, Lisa A., and Thomas C. Voice. Brownfield Redevelopment Guidebook for Michigan. Ed. Robert V. Colangelo, et al. Chicago: Robert V. -

Bereikbaarheid in Rotterdam, Zo Regelen We Dat!

Bereikbaarheid in Rotterdam, zo regelen we dat! Rotterdam is een stad waar op elk moment van de dag werkzaamheden uitgevoerd worden. Rotterdam is ook een stad die haar infrastructuur, de bereikbaarheid en de samenwerking met externe partijen hoog in het vaandel heeft staan. Met elkaar houden we Rotterdam bereikbaar! Daar waar gewerkt wordt, komen de verkeersdoorstroming en bereikbaarheid regelmatig in het geding. Daarom heeft Rotterdam een werkwijze ontwikkeld om samen met alle betreffende partijen voorafgaand aan de werkzaamheden de gevolgen voor de bereikbaarheid in kaart te brengen: bereikbaarheid in Rotterdam, zo regelen we dat! Stadsbeheer werkt gebiedsgericht vanuit 6 gebieden www.rotterdam.nl 0800-1545 stadswinkel Prins Alexander Centrum / Delfshaven Noord-West: Hillegersberg-Schiebroek / Overschie / bedrijventerrein Spaanse Polder Noord-Oost: Kralingen-Crooswijk / Noord Zuid-Oost: Feijenoord / IJsselmonde Zuid-West: Charlois / Hoogvliet / Pernis / Rozenburg / Hoek van Holland / Havengebied Contact Gebiedskantoren Centrum/Delfshaven: 14010 [email protected] Bereikbaarheid Noord-Oost: 14010 [email protected] Noord-West: 14010 [email protected] Zuid-Oost: 14010 [email protected] in Rotterdam Zuid-West: 14010 [email protected] Prins Alexander: 14010 [email protected] Gemeente Rotterdam, Cluster Stadsbeheer Kijk voor meer informatie en de gebiedsindeling op www.rotterdam.nl/bereikbaarheid zo regelen we dat! Maart 2015 Regie in de gebieden Zo werkt het! Extra uitleg Intake in het gebied U meldt uw voorgenomen werkzaamheden in de bui- Hinderparameters tenruimte bij het betreffende Stadsbeheer Gebieds- Er worden 6 hinderparameters gehanteerd om de kantoor voor een intake. Deze intake vindt zo vroeg impact van uw werkzaamheden te definiëren. mogelijk in het proces plaats, bij voorkeur al voordat De som van deze parameters bepaalt de uiteindelij- een initiatief uitgekristalliseerd is tot een project. -

The Tradition of Making Polder Citiesfransje HOOIMEIJER

The Tradition of Making Polder CitiesFRANSJE HOOIMEIJER Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. ir. K.C.A.M. Luyben, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 18 oktober 2011 om 12.30 uur door Fernande Lucretia HOOIMEIJER doctorandus in kunst- en cultuurwetenschappen geboren te Capelle aan den IJssel Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof. dr. ir. V.J. Meyer Copromotor: dr. ir. F.H.M. van de Ven Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnificus, voorzitter Prof. dr. ir. V.J. Meyer, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor dr. ir. F.H.M. van de Ven, Technische Universiteit Delft, copromotor Prof. ir. D.F. Sijmons, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. ir. H.C. Bekkering, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. dr. P.J.E.M. van Dam, Vrije Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof. dr. ir.-arch. P. Uyttenhove, Universiteit Gent, België Prof. dr. P. Viganò, Università IUAV di Venezia, Italië dr. ir. G.D. Geldof, Danish University of Technology, Denemarken For Juri, August*, Otis & Grietje-Nel 1 Inner City - Chapter 2 2 Waterstad - Chapter 3 3 Waterproject - Chapter 4 4 Blijdorp - Chapter 5a 5 Lage Land - Chapter 5b 6 Ommoord - Chapter 5b 7 Zevenkamp - Chapter 5c 8 Prinsenland - Chapter 5c 9 Nesselande - Chapter 6 10 Zestienhoven - Chapter 6 Content Chapter 1: Polder Cities 5 Introduction 5 Problem Statement, Hypothesis and Method 9 Technological Development as Natural Order 10 Building-Site Preparation 16 Rotterdam -

Met De Auto Openbaar Vervoer

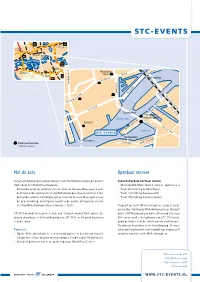

A13 A20 E25 E19 Knooppunt Terbregseplein Knooppunt Kethelplein Knooppunt Kleinpolderplein A4 dijk kels A16 Beu E19 ’ Knooppunt s d G r Ridderkerk leva r ou Knooppunt A15 a Metrostation sb Beneluxplein v aa e Beurs Blaak M Knooppunt A15 n Vaanplein A16 d i j Willemsbrug A29 k w Westblaak a Coolsingel l s je p om o B at a Oranjeboomstraat nstr ss e chu Ro d an Rosestraat tel Vas Erasmusbrug Stieltjesstraat Metrostation Nieuwe Maas Wilhelminaplein Posthumalaan Euromast M Laan op Zuid Wilhelminakade Rijnhaven Rijnhavenbrug Maastunnel Rijnhaven Z.z. Veerlaan M Metro en tram stop Brede Hilledijk Wilhelminaplein Met de auto Openbaar vervoer Vanaf alle belangrijke aanvoerwegen naar Rotterdam volgt u de borden Vanaf Rotterdam Centraal station: Rotterdam Centrum/Erasmusbrug. • Metrolijn D/E (Rotterdam Centraal - Spijkenisse) • Komende vanaf de zuidkant van de rivier de Nieuwe Maas gaat u voor • Tram 20 (richting Lombardijen) de Erasmusbrug linksaf richting Wilhelminapier/havennummer 1240. • Tram 23 (richting Beverwaard) • Komende vanaf de noordzijde van de rivier de Nieuwe Maas gaat u over • Tram 25 (richting Carnisselande) de Erasmusbrug. Vervolgens neemt u de eerste afslag naar rechts richting Wilhelminapier/havennummer 1240. Stap uit op halte Wilhelminaplein. Loop in zuid- westelijke richting de Wilhelminakade op. U houdt STC B.V. bevindt zich aan het einde van “Cruiseterminal Rotterdam”. De dan het KPN gebouw aan uw rechterhand. Na circa glazen draaideur is de hoofdingang van STC B.V., in dit pand bevinden 500 meter vindt u het gebouw van STC B.V. (in dit zich de zalen. pand bevinden zich de zalen) aan de rechterkant. De glazen draaideur is de hoofd ingang. -

Residents Experience the Effects of Gentrification in Middelland and Katendrecht

[I] “You cannot live with the present, if you forget the past” An insight on how ‘in between’ residents experience the effects of gentrification in Middelland and Katendrecht Bachelor thesis Geography, Planning & Environment Marijke Clarisse S4394682 Mentor: Ritske Dankert Radboud University Nijmegen Faculty of Management August 2016 [II] Preface To Complete my third year and thus the baChelor SoCial Geography, Spatial Planning and Environment at the Radboud University of Nijmegen, I have been working on my bachelor thesis for the last semester. The researCh I did was on the experienCes of gentrifiCation in Rotterdam for residents that are not taken into aCCount in the theories and how the positive governmental poliCy on gentrifiCation Could influenCe this: First of all I would like to thanks my mentor Ritske Dankert who guided me through the proCess of writing this thesis in the many feedbaCk sessions. I also would like to thank the people who took the time and effort to help me by providing me with the information needed through interviews. And all people who helped me through the past three years and especially the last few months: thank you! Marijke Clarisse Nijmegen, 12 augustus [III] Summary GentrifiCation has reCeived a lot of attention in the last Couple of years. Not only the United States of AmeriCa or the United Kingdom are dealing with gentrifiCation, the phenomenon has reaChed the Netherlands as well. In the Netherlands gentrifiCation is used by the government as a strategy for solving the problem of segregation in Certain neighbourhoods, whiCh makes those neighbourhoods less liveable. If the government wants to keep using gentrifiCation as a way to revitalise disadvantaged neighbourhoods in the City, it will have to find a way to meet the needs of both the middle class newcomers to the area, as well as the indigenous residents that want to keep living there.