Crafts, Boys, Ernest Thompson Seton, and the Woodcraft Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Table of Contents

Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training Table of Contents Instructions for Instructors 5 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training and the Eight Methods of Scouting 5 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training and the Six Steps of a Team Meeting 6 The Goal of This Training 6 Who Is Eligible to Take Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training? 7 Course Schedule 8 Varsity Program Management 8 Session Setting 9 Session Format 9 Keep This In Mind 9 A Final Word 10 Local Resources Summary 11 Session One—Setting Out: The Role of the Varsity Coach Preopening Activity 15 Welcome and Introductions 17 Course Overview 21 The Role of the Varsity Coach 29 Team Organization 33 Team Meetings 43 Working With Young Men 57 Team Leaders’ Meetings 69 Session Two—Mountaintop Challenges: The Outdoor/Sports Program and the Advancement Program Preopening Activity 79 Introduction to Session Two 83 The Sizzle of the Outdoor Program 87 Varsity Coach Leader Specific Training 1 Nuts and Bolts of the Outdoor Program 93 Outdoor Program Squad/Group Activity 105 Reflection 115 Advancement 119 Session Three—Pathways to Success: Program Planning and Team Administration Preopening Activity 135 Introduction to Session Three 137 Program Planning 141 Membership 153 Paperwork 159 Finances 163 The Uniform 167 Other Training Opportunities 171 Summary and Closing 177 Available on CD-ROM • Schedule of Sessions One through Three • Local Resources Summary • The first page of the The Varsity Scout Guidebook • Role-Play One—Varsity Coach and Team Captain Review -

BSA Brand Guidelines Real-World Examples 97 Introduction

Boy Scouts of America Brand Guidelines BSALast Brand revised Guidelines July 2019 Table of Contents Corporate Brand Scouting Sub-Brands Digital Guidelines Scouting Architecture 6 Scouts BSA 32 Guiding Principles 44 WEBSITES 69 Prepared. For Life.® 7 Position and Identity 33 Web Policies 45 Information Architecture 70 Vision and Mission 8 Cub Scouting 34 TYPOGRAPHY 46 Responsive Design 71 Brand Position, Personality, and Communication Elements 9 Position and Identity 35 Typefaces for Digital Projects 47 Forms 72 Corporate Trademark 10 Venturing 36 Hierarchy 48 Required Elements 73 Corporate Signature 11 Position and Identity 37 Best Practices 49 Real-World Examples 74 The Activity Graphic 12 Sea Scouting 38 Typography Pitfalls 50 MOBILE 75 Prepared. For Life.® Trademark 13 Position and Identity 39 DIGITAL COLOR PALETTES 51 Interface Design 76 Preparados para el futuro.® 14 Primary Boy Scouts of America Colors 52 Using Icons in Apps 77 BSA Extensions Trademark and Logo Protection 15 Secondary Boy Scouts of America Colors 53 Mobile Best Practices 78 BSA Extensions Brand Positioning BSA Corporate Fonts 17 41 Cub Scouting 54 Resources 79 Council, Group, Department, and Team Designation PHOTOGRAPHY 18 42 Scouts BSA 55 Real-World Example: BSA Camp Registration App 80 Photography 19 Venturing 56 EMAIL 81 Living Imagery 20 Sea Scouting 57 HTML Email 82 Doing Imagery 21 Choosing the Correct Color Palette 58 Email Signatures 83 Best Practices 22 IMAGERY 59 Email Best Practices 84 Image Pitfalls 23 Texture 60 ONLINE ADVERTISING 85 Resources 24 Icons -

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’S Historical Membership Patterns

A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns BY Matthew Finn Hubbard Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert ____________________________ Dr. Terry Slocum ____________________________ Dr. Xingong Li Date Defended: 11/22/2016 The Thesis committee for Matthew Finn Hubbard Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Cartographic Depiction and Exploration of the Boy Scouts of America’s Historical Membership Patterns ____________________________ Chairperson Dr. Stephen Egbert Date approved: (12/07/2016) ii Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to examine the historical membership patterns of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) on a regional and council scale. Using Annual Report data, maps were created to show membership patterns within the BSA’s 12 regions, and over 300 councils when available. The examination of maps reveals the membership impacts of internal and external policy changes upon the Boy Scouts of America. The maps also show how American cultural shifts have impacted the BSA. After reviewing this thesis, the reader should have a greater understanding of the creation, growth, dispersion, and eventual decline in membership of the Boy Scouts of America. Due to the popularity of the organization, and its long history, the reader may also glean some information about American culture in the 20th century as viewed through the lens of the BSA’s rise and fall in popularity. iii Table of Contents Author’s Preface ................................................................................................................pg. -

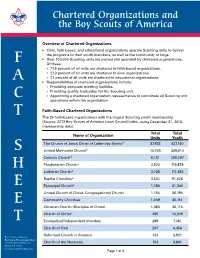

F a C T S H E E T F a C T S H E

Chartered Organizations and the Boy Scouts of America Overview of Chartered Organizations • Civic, faith-based, and educational organizations operate Scouting units to deliver the programs to their youth members, as well as the community at large. • Over 100,000 Scouting units are owned and operated by chartered organizations. F Of these: º 71.5 percent of all units are chartered to faith-based organizations. º 21.3 percent of all units are chartered to civic organizations. A º 7.2 percent of all units are chartered to educational organizations. • Responsibilities of chartered organizations include: º Providing adequate meeting facilities. º Providing quality leadership for the Scouting unit. C º Appointing a chartered organization representative to coordinate all Scouting unit operations within the organization. T Faith-Based Chartered Organizations The 25 faith-based organizations with the largest Scouting youth membership (Source: 2013 Boy Scouts of America Local Council Index, using December 31, 2013, membership data): Total Total Name of Organization Units Youth The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints* 37,933 437,160 S United Methodist Church* 10,703 349,614 Catholic Church* 8,131 259,297 H Presbyterian Church* 3,520 119,879 Lutheran Church* 3,728 111,483 Baptist Churches* 3,532 91,526 E Episcopal Church* 1,180 41,340 United Church of Christ, Congregational Church 1,154 36,194 E Community Churches 1,009 30,114 Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) 1,083 30,113 Church of Christ* 495 13,559 T Evangelical/independent churches 299 7,740 Church of God 207 4,354 Boy Scouts of America Reformed Church in America 124 3,921 Research & Program Innovation 1325 W. -

Boy Scout/Varsity Scout

Boy Scout/Varsity Scout Uniform Inspection Sheet Uniform Inspection. Conduct the uniform inspection with common sense; the basic rule is neatness. Boy Scout Handbook n 15 pts. The Boy Scout Handbook is considered part of a Scout’s uniform. General Appearance. Allow 2 points for each: n 10 pts. Good posture n Clean face and hands n Combed hair n Neatly dressed n Clean fingernails Notes ______________________________________________________ Headgear. All troop members must wear the headgear chosen by vote of the troop/team. 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Shirt and Neckwear. Official shirt or official long- or short-sleeve uniform shirt with green 10 pts. or blaze orange shoulder loops on epaulets. The troop/team may vote to wear a neckerchief, bolo tie, or no neckwear. The troop/team has the choice of wearing the neckerchief over the turned- under collar or under the open collar. In any case, the collar should be unbuttoned and the shirt should be tucked in. Notes ______________________________________________________ Pants/Shorts. Official pants or official uniform pants or shorts; no cuffs. 10 pts. (Units have no option to change.) Notes ______________________________________________________ Belt. Official Boy Scout web with BSA insignia on buckle; or official leather with international- 5 pts. style buckle or buckle of your choice, worn only if voted by the troop/team. Members wear one of the belts chosen by vote of the troop/team. Notes ______________________________________________________ Socks. Official socks with official shorts or pants. (Long socks are optional with shorts.) 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Shoes. Leather or canvas, neat and clean. 5 pts. Notes ______________________________________________________ Registration. -

Cub Scout Camping Policies

DEL-MAR-VA COUNCIL, INC. BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA CUB SCOUT CAMPING POLICIES The following is a summary of BSA and Del-Mar-Va Council policies pertaining to Cub Scout and Webelos camping. CUB SCOUT CAMPING – Tigers, Wolves, Bears, and Webelos may participate in Cub Scout Resident Camp, Pack, District, or Council-sponsored Cub/parent overnights, or Cub Scout Day Camp. Cub Scouts may not attend camp with a Boy Scout Troop. Tigers must be accompanied by a parent or legal guardian. Camping may take place at a council camp property, or at city, state, or national park or council approved facility only. No tent camping will take place between November 1st and April 15th. Tent camping should be done only in warm weather and at sites reasonably close to home. The focus of a campout should be on Cub Scout outdoor activities and Adventures. PACK FAMILY CAMPING – Each Pack must have at least one adult that has completed BALOO or WELOT training in attendance at a campout. At least one attending adult must have completed Youth Protection training. Training cards must be shown to the Campmasters or camp administration upon check-in. Before a campout takes place, the Pack leadership must ensure that each family that will be participating receives an orientation on outdoor camping and Youth Protection from someone knowledgeable about the outdoors and BSA policies. The Buddy System must be in use at all times. No tent camping may take place between November 1st and April 15th. The adult to child ratio must be one to one for ALL Cub Scout overnight activities, exceptions may be made only for siblings. -

Pawhuska Is Home to Nation's First Boy Scout Troop...Scout's Honor!

Cowboy Hats Oklahoma is Home to & Hard Hats First Boy Scout Troop 4 Be an Angel 2 3 this Christmas Pawhuska is Home to Nation’s First Boy Scout Troop....Scout’s Honor! Oklahoma was a brand new state when Rev. and earned English badges,” she says, adding “it John F. Mitchell arrived on the plains of Osage was designated Troop #1.” County. What he found in Pawhuska were people “In fact, Ed Tinker who owned the local anxious to develop the area and to welcome the newspaper, bought the uniforms and paid for world. But for all that enthusiasm, there was little them to be shipped here from England. His son interest being paid to the area’s young people. Alex was one of the troop members.” Rev. Mitchell knew just what to do about Taylor says the new Scouts did many that. And what he did made history. activities Scouts still enjoy today. “They went on MitchellMitchell was on assignment fromfrom the ChurchChurch camping trips, learned wood crafts, survivalsurvival tech- of EnglandEngland to Pawhuska’sPawhuska’s St.St. Thomas EpiscopalEpiscopal niques, and howhow to use many of the resourcesresources Church.Church. The BritishBritish minister was an associ- that could be found out in the wild, while ate of LordLord RobertRobert Baden-Powell,Baden-Powell, still respectingrespecting and preservingpreserving those who founded the BoyBoy Scouts of resources,”resources,” shes says. England,England, and he had workedworked “But“But they did some things with Scouting while there.there. HeHe differentlydifferently too.too. ForFor exam- felt the beautiful, yetyet still ple, they sang ‘God‘God SaveSave untamed areaarea of northernnorthern the Queen,’”Queen,’” she laughs. -

Glossary of Scouting Terms Activities and Civic Service Committee

GLOSSARY OF SCOUTING TERMS activities and civic service committee. The council or Boy Scout. A registered youth member of a Boy Scout district committee responsible for planning, promoting troop or one registered as a Lone Scout. Must have and operating activities. completed the fifth grade and be 11 years old, or have earned the Arrow of Light Award but not yet be 18 advanced training. In-depth training for experienced years old. adult leaders, such as Wood Badge. Boy Scouts of America (BSA). A nationwide organiza- advancement. The process by which a Boy Scout meets tion founded February 8, 1910, and chartered by the certain requirements and earns recognition. U.S. Congress June 15, 1916. Alpha Phi Omega (APO). A coeducational service Boys’ Life magazine. The magazine for all boys, fraternity organized in many colleges and universities. published by the Boy Scouts of America. It was founded on the principles of the Scout Oath and Law. Bronze Palm. An Eagle Scout may receive this recogni- tion by earning five additional merit badges and com- Aquatics Instructor, BSA. A five-year certification pleting certain other requirements. awarded to an adult who satisfactorily completes the aquatics section at a BSA National Camping School. Brotherhood membership. The second and final induc- tion phase of membership in the Order of the Arrow. area director. A professional Scouter on a regional staff who relates to and works with an area president in BSA Lifeguard. A three-year certification awarded giving direct service to local councils. to Boy Scouts who meet prescribed requirements in aquatics skills. -

Suggested Presentation of Masonic Scouter Awards

Suggested Presentation of Masonic Scouter Awards Masonic Official: Freemasonry is based on service, and the exemplification of moral truth, which is essential for good role models. The Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, in cooperation with the Boy Scouts of America, created the Daniel Carter Beard Masonic Scouter Award as a national award program for Masons who exemplify the Scout Law and Masonic Virtues, in service to the Scouting Program. Masonic Official: In the late 1800’s, Daniel Carter Beard created a program called the “Boy Pioneers” that inspired Lord Robert Baden-Powell to create the Boy Scouts in England. The Boy Scout program came to the United States in 1910 when Dan Beard merged his organization into the Boy Scouts of America and became its first National Commissioner. A Master Mason in New York, Brother Dan Beard stands as a fine example of how a Mason can live a life of Masonic Service to mankind, by reaching out and working with youth in the local community. Masonic Official: The award consists of a Masonic medallion suspended from a blue and silver neck ribbon, which can be worn at any Masonic or Scout gathering, a certificate, and a traditional Scouting knot patch authorized by the Boy Scouts of America as the “Community Organization Award,” to be worn by Scouters above the left shirt pocket of the uniform. Masonic Official: Today, this presentation of the Daniel Carter Beard Masonic Scouter Award is being made to the following deserving (brother/brethren) who (was/were) nominated by (his/their) Lodge, approved by the local Scout Executive, and authorized by the Grand Lodge. -

Council & Unit Planning Guide

COUNCIL & UNIT PLANNING GUIDE PHILMONT SCOUT RANCH TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Preparation for Philmont Scout Ranch ................................................................................................................................... 3 Financial Fees & Expedition Budget ...................................................................................................................................... 14 First Aid & Health .................................................................................................................................................................. 17 Travel & Transportation ........................................................................................................................................................ 24 Upon Arrival .......................................................................................................................................................................... 28 Resources .............................................................................................................................................................................. 31 Other Opportunities .............................................................................................................................................................. 31 Council & Unit Planning Guide | 1 -

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946

Ernest Thompson Seton 1860-1946 Ernest Thompson Seton was born in South Shields, Durham, England but emigrated to Toronto, Ontario with his family at the age of 6. His original name was Ernest Seton Thompson. He was the son of a ship builder who, having lost a significant amount of money left for Canada to try farming. Unsuccessful at that too, his father gained employment as an accountant. Macleod records that much of Ernest Thompson Seton 's imaginative life between the ages of ten and fifteen was centered in the wooded ravines at the edge of town, 'where he built a little cabin and spent long hours in nature study and Indian fantasy'. His father was overbearing and emotionally distant - and he tried to guide Seton away from his love of nature into more conventional career paths. He displayed a considerable talent for painting and illustration and gained a scholarship for the Royal Academy of Art in London. However, he was unable to complete the scholarship (in part through bad health). His daughter records that his first visit to the United States was in December 1883. Ernest Thompson Seton went to New York where met with many naturalists, ornithologists and writers. From then until the late 1880's he split his time between Carberry, Toronto and New York - becoming an established wildlife artist (Seton-Barber undated). In 1902 he wrote the first of a series of articles that began the Woodcraft movement (published in the Ladies Home Journal). The first article appeared in May, 1902. On the first day of July in 1902, he founded the Woodcraft Indians, when he invited a group of boys to camp at his estate in Connecticut and experimented with woodcraft and Indian-style camping. -

History of Venturing

When Did Venturing Begin? Officially Venturing was created by the Boy Scouts of America’s executive board on February 9, 1998. However if you ask Bill Evans, Associate Director, Venturing, who was there that day and helped create Venturing, he would expand a little. In 1995, the Outdoor Exploring Committee chaired by Dr. Dick Miller of Waynesboro, Virginia, met in Long Key, Florida. The primary purpose of the meeting was to address the issue of how to support and sustain the amazing growth that outdoor Exploring was enjoying. During a five year period in the early 90s, Outdoor Exploring had grown 94% to almost a hundred thousand members. What resulted from that committee meeting was what is now known as the Ranger Award, the Silver Award, and Bronze Awards. Evans said that when the committee would come up with an idea, it would sound familiar. Then they would refer to a 1950 edition of the Explorer Handbook and find their idea had already been applied years ago. So, if you are a history buff and have an early edition Explorer Handbook, you can see the many similarities between early days Exploring and today’s Venturing. If you really want to trace the roots of Venturing, according to Evans, you have to go way back. Evans says the need for a senior Boy Scout program probably surface the second day after Scouting started in the United States in 1910. Actually in the very first national executive board meeting report, it is stated that there was a discussion about losing older boys.