The International Space Station: Legal Framework and Current Status, 64 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Space Station Intergovernmental Agreement

AGREEMENT AMONG THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, GOVERNMENTS OF MEMBER STATES OF THE EUROPEAN SPACE AGENCY, THJ3 GOVERNMENT OF JAPAN, THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION, AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CONCERNING COOPERATION ON THE CIVIL INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION , - Table of Contents Arkle 1 Object and Scope Art~le 2 International Rights and Obhgatlons Article 3 Detimtlons Artxle 4 Cooperatmg Agencies Article 5 Reglstratlon, lunsd~cl~on and Control Article 6 Ownershrp of Elements and Equipment Article 7 Management Artxle 8 De&&d Des1811and Development Artde 9 Utthzation Article 10 Operation Article I I crew Article I2 Transportation Article 13 Communlcatrons Article I4 Evolution Article I5 Fundmg Article 16 Cross-Waiver of Liability Article I7 Llabillty Convention Article 18 Customs and Immigmtlon Article 19 Exchange of Data and Goods Article 20 Treatment of Data and Goods in Transit Article 2 1 Intellectual Property tiicle 22 Crimmal Junsdic~on Artxle 23 Consultations Article 24 Space StatIon Cooperation Review Alticle 25 Entry into Force Arlicle 26 Opmti~e Effect as between Certain PartIes Artxle 27 Amendments Article 28 Withdrawal Annex Space Station Elements to be Provided by the Partners I - II I The Government of Canada (heremafter also “Canada”), The Governments of the Kingdom of Belgium, the Kmgdom of Denmark, the French Republic, the Federal Republic of Germany, the Italian Repubhc, the Kmgdom of the Netherlands, the Kingdom of Norway, the Kingdom of Spam, the Kingdom of Sweden, the Swiss Confederation, and -

XXIX Congress Report XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 Photos: OEWF

XXIX Congress Report XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 Photos: OEWF 1 John-David Bartoe, 2 Alexander Ivanchenkov, 3 Ulrich Walter, 4 Gerhard Thiele, 5 Georgi Iva- nov, 6 Yuri Gidzenko, 7 Bertalan Farkas, 8 Kevin Ford, 9 Pavel Vinogradov, 10 Charlie Walker, 11 Kimiya Yui, 12 Anatoli Artsebarskii, 13 Shannon Lucid, 14 Reinhold Ewald, 15 Claudie Haigneré, 16 Joe Acaba, 17 Ernst Messerschmid, 18 Jan Davis, 19 Franz Viehbock, 20 Loren Shriver, 21 Miroslaw Hermaszewski. 22 Sultan bin Salman al-Saud, 23 Yang Liwei, 24 Richard Garriott, 25 Mark Brown, 26 Carl Walz, 27 Bill McArthur, 28 Owen Garriott, 29 Anna Fisher, 30 George Zam- ka, 31 Rick Hieb, 32 Jerry Ross, 33 Alexander Volkov, 34 André Kuipers, 35 Jean-Pierre Haign- eré, 36 Toktar Aubakirov, 37 Kay Hire, 38 Michael Fincke, 39 John Fabian, 40 Pedro Duque, 41 Michael Foreman, 42 Sergei Avdeev, 43 Vladimir Kovolyonok, 44 Alexandar Aleksandrov, 45 Alexander Alexandrov, 46 Drew Feustel, 47 Dumitru Prunariu, 48 Alexei Leonov, 49 Rusty Sch- weickart, 50 Klaus-Dietrich Flade, 51 Anton Shkaplerov, 52 Alexander Samokutyaev, 53 Sergei Krikalev, 54 Viktor Savinykh, 55 Soichi Noguchi, 56 Bonnie Dunbar, 57 Vladimir Aksyonov, 58 Scott Altman, 59 Yuri Baturin, 60 Susan Helms, 61 Ulf Merbold, 62 Stephanie Wilson, 63 Chiaki Mukai, 64 Charlie Camarda, 65 Julie Payette, 66 Dick Richards, 67 Yuri Usachev, 68 Michael Lo- pez-Alegria, 69 Jim Voss, 70 Rex Walheim, 71 Oleg Atkov, 72 Bobby Satcher, 73 Valeri Tokarev, 74 Sandy Magnus, 75 Bo Bobko, 76 Helen Sharman, 77 Susan Kilrain, 78 Pam Melroy, 79 Janet Kavandi, 80 Tony Antonelli, 81 Sergei Zalyotin, 82 Frank De Winne, 83 Alexander Balandin, 84 Sheikh Muszaphar, 85 Christer Fuglesang, 86 Nikolai Budarin, 87 Salizhan Sharipov, 88 Vladimir Titov, 89 Bill Readdy, 90 Bruce McCandless II, 91 Vyacheslav Zudov, 92 Brian Duffy, 93 Randy Bresnik, 94 Oleg Artemiev XXIX Planetary Congress • Austria • 2016 One hundred and four astronauts and cosmonauts from 21 nations gathered Oc- tober 3-7, 2016 in Vienna, Austria for the XXIX Planetary Congress of the Associa- tion of Space Explorers. -

A Feasibility Study for Using Commercial Off the Shelf (COTS)

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2011 A Feasibility Study for Using Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) Hardware for Meeting NASA’s Need for a Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) to the International Space Station - [COTS]2 Chad Lee Davis University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Aerodynamics and Fluid Mechanics Commons, Other Aerospace Engineering Commons, and the Space Vehicles Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Chad Lee, "A Feasibility Study for Using Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) Hardware for Meeting NASA’s Need for a Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) to the International Space Station - [COTS]2. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2011. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/965 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Chad Lee Davis entitled "A Feasibility Study for Using Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) Hardware for Meeting NASA’s Need for a Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) to the International Space Station - [COTS]2." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Aerospace Engineering. -

Development of the Crew Dragon ECLSS

ICES-2020-333 Development of the Crew Dragon ECLSS Jason Silverman1, Andrew Irby2, and Theodore Agerton3 Space Exploration Technologies, Hawthorne, California, 90250 SpaceX designed the Crew Dragon spacecraft to be the safest ever flown and to restore the ability of the United States to launch astronauts. One of the key systems required for human flight is the Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS), which was designed to work in concert with the spacesuit and spacecraft. The tight coupling of many subsystems combined with an emphasis on simplicity and fault tolerance created unique challenges and opportunities for the design team. During the development of the crew ECLSS, the Dragon 1 cargo spacecraft flew with a simple ECLSS for animals, providing an opportunity for technology development and the early characterization of system-level behavior. As the ECLSS design matured a series of tests were conducted, including with humans in a prototype capsule in November 2016, the Demo-1 test flight to the ISS in March 2019, and human-in-the-loop ground testing in the Demo-2 capsule in January 2020 before the same vehicle performs a crewed test flight. This paper describes the design and operations of the ECLSS, the development process, and the lessons learned. Nomenclature AC = air conditioning AQM = air quality monitor AVV = active vent valve CCiCap = Commercial Crew Integrated Capability CCtCap = Commercial Crew Transportation Capability CFD = computational fluid dynamics conops = concept of operations COPV = composite overwrapped -

Paper Session III-B - Space Station On-Orbit Assembly and Operation

1991 (28th) Space Achievement: A Global The Space Congress® Proceedings Destiny Apr 25th, 1:00 PM - 4:00 PM Paper Session III-B - Space Station On-Orbit Assembly and Operation L. P. Morata Vice President, Deputy General Manager, McDonnell Douglas Space Systems Company, Huntington Beach CA F. David Riel Deputy Director, System Engineering and Integration, McDonnell Douglas Space Systems Company- Space Station Division Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings Scholarly Commons Citation Morata, L. P. and Riel, F. David, "Paper Session III-B - Space Station On-Orbit Assembly and Operation" (1991). The Space Congress® Proceedings. 9. https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings/proceedings-1991-28th/april-25-1991/9 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Space Congress® Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPACE STATION FREEDOM ASSEMBLY AND OPERATIONS Larry P. Morata Vice President, Deputy Project Manager—DDT&E McDonnell Douglas Space Systems Company-Space Station Division Huntington Beach, California and F. David Kiel Deputy Director, System. Engineering and Integration McDonnell Douglas Space Systems Company-Space Station Division Huntington Beach, California ABSTRACT Eight Man. Crew Capability (EMCC) by 31 December 2000 as shown, in Figure 1. The United States and its international partners are well Recent design, on the way to developing Space Station Freedom which will changes as part: of the SSF program restructure activity have be a very large orbiting facility with many capabilities for altered the Space Station configu ration and design from conducting space operations. -

Final Report of the International Space Station Independent Safety

I Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................ 1 Principal Observations ..................................................................................... 3 Principal Recommendations ............................................................................. 3 1. Introduction..................................................................................................... 5 Charter/Scope ................................................................................................... 5 Approach........................................................................................................... 5 Report Organization ......................................................................................... 5 2. The International Space Station Program.................................................... 7 International Space Station Characteristics..................................................... 8 3. International Space Station Crosscutting Management Functions............ 12 Robust On-Orbit Systems.................................................................................. 12 The Design ........................................................................................................ 12 Verification Requirements ................................................................................ 12 Physical (Fit) Verification ................................................................................ 13 Multi-element Integrated Test.......................................................................... -

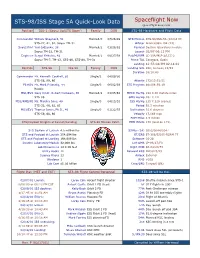

Spaceflight Now STS-98/ISS Stage 5A Quick-Look Data

STS-98/ISS Stage 5A Quick-Look Data Spaceflight Now spaceflightnow.com Position ISS-1 (Soyuz Up/STS Down) Family DOB STS-98 Hardware and Flight Data Commander William Shepherd, 51 Married/0 07/26/49 STS Mission STS-98/ISS-5A (102nd flt) STS-27, 41, 52, Soyuz TM-31 Orbiter Atlantis/OV-104 (23) Soyuz Pilot Yuri Gidzenko, 38 Married/2 03/26/62 Payload Destiny laboratory module Soyuz TM-22, TM-31 Launch 02/07 06:13 PM Engineer Sergei Krikalev, 42 Married/1 08/27/58 Pad/MLP/FR LC-39A/MLP-2/LCC-2 Soyuz TM-7, TM-12, STS-60, STS-88, TM-31 Prime TAL Zaragoza, Spain Landing 12:53:08 PM 02.18.01 Position STS-98 ISS-5A Family DOB Landing Site KSC, Runway 15/33 Duration 10/18:40 Commander Mr. Kenneth Cockrell, 50 Single/2 04/09/50 STS-56, 69, 80 Atlantis 172/13:51:51 Pilot/IV Mr. Mark Polansky, 44 Single/0 06/02/56 STS Program 881/06:59:19 Rookie MS1/EV2 Navy Cmdr. Robert Curbeam, 38 Married/2 03/05/62 MECO Ha/Hp 194 X 46 statute miles STS-85 OMS Ha/Hp 201 X 121 MS2/RMS/FE Ms. Marsha Ivins, 49 Single/0 04/15/51 ISS Ha/Hp 235 X 229 (varies) STS-32, 46, 62, 81 Period 92.3 minutes MS3/EV1 Thomas Jones, Ph.D., 46 Single/0 01/22/55 Inclination 51.6 degrees STS-59, 68, 80 Velocity 17,169 mph EOM Miles 4.5 million STS/Payload Weights at Launch/Landing STS-98 Mission Patch EOM Orbits 170 (land on 171) STS System at Launch 4.5 million lbs SSMEs (2A) 2052/2044/2047 STS and Payload at Launch 254,694 lbs ET/SRB ET-106/BI105-RSRM 77 STS and Payload at Landing 198,909 lbs Software OI-28 Destiny Laboratory Module 32,000 lbs Left OMS LP-03/27/F3 Lab Dimensions 14 -

Glex-2021 – 6.1.1

Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX 2021), St Petersburg, Russian Federation, 14-18 June 2021. Copyright ©2021 by Christophe Bonnal (CNES). All rights reserved. GLEX-2021 – 6.1.1 Human spaceflight from Guiana Space Center Ch. Bonnal1* – J-M. Bahu1 – Ph. Berthe2 – J. Bertrand1 – Ch. Bonhomme1 – M. Caporicci2 J-F. Clervoy3 – N. Costedoat4 – E. Coletti5 – G. Collange5 – G. Debas5 – R. Delage6 – J. Droz5 E. Louaas1 – P. Marx8 – B. Muller6 – S. Perezzan1 – I. Quinquis5 – S. Sandrone7 D. Schmitt2 – V. Taponier1 1 CNES Launcher Directorate, Pairs, France – 2 ESA Human & Robotic Exploration Directorate, ESTEC, Noordwijk, Netherlands – 3 Astronaut Novespace, Paris, France – 4CNES Guiana Space Center, Kourou, France 5ArianeGroup, Les Mureaux, France – 6Airbus Defence & Space, Toulouse, France – 7Airbus Defence & Space, Bremen Germany – 8Consultant, Paris, France * Corresponding Author Abstract The use of Space has drastically evolved these last ten years. Tomorrow will see easier and cheaper access to Space, satellite servicing, in-orbit manufacturing, human private spaceflights to ever increasing number of Orbital Stations, road to the Moon, Asteroids, Mars. It seems fundamental to make sure we can rely on robust, reliable, frequent and affordable access to and from LEO with both automatic systems and human missions; such systems are the bricks with which all the future operations in Space will be built. Independent human access to space from Europe for our astronauts is a key to any future in Space. It has been studied in depth since the 80's with Hermes Spaceplane, then through numerous studies, pre- development activities, and demonstrations such as ARD, X38-CRV or IXV, which now allow Europe to reconsider such an endeavor with a much higher confidence. -

Soyuz Launch Brochure

Incredible Adventures is excited to offer a unique opportunity – a chance to visit the famous Baikonur Cosmodrome and observe a manned launch of a Russian Soyuz spacecraft. You’ll be completely immersed in the electric atmosphere surrounding a launch. You’ll explore Baikonur’s launch sites, museums and most historic places. Join IA for an Incredible Space Adventure. Highlights of Your Incredible Baikonur Adventure 800-644-7382 or 941-346-2603 www.incredible-adventures.com Observe roll-out and installation of the Soyuz rocket at launch pad. Attend international press conference of main and back- up crews. See the farewell of the crew at the cosmonaut hotel. Hear crew's ready-to-go official report. See launch of the Soyuz rocket, something you’ll never forget. Incredible Baikonur Adventure Day 1 Meet IA representative at the airport. Flight from Moscow to Baikonur .Transfer to the hotel. Time to relax. Day 2 Breakfast in the hotel Transfer to Baikonur Cosmodrome Roll-out of the Soyuz Rocket. (Follow the Soyuz to its launch site.) Observe installation of the rocket on the launch pad. Visit to the integration building of Soyuz and Progress spaceships. Transfer back to town. Visit to the International Space School. 9 Day 3 Breakfast in the hotel. Visit Museum of History Cosmodrome Baikonur. Enjoy general sightseeing in the town of Baikonur (learn history of the town, visit memorials and monuments). Transfer to Cosmonaut hotel. International press conference with the main and backup crews of Soyuz-TMA vehicle. Walk along the historical alley of Cosmonauts where personalized trees are planted. -

Cubesat Mission: from Design to Operation

applied sciences Article CubeSat Mission: From Design to Operation Cristóbal Nieto-Peroy 1 and M. Reza Emami 1,2,* 1 Onboard Space Systems Group, Department of Computer Science, Electrical and Space Engineering, Luleå University of Technology, Space Campus, 981 92 Kiruna, Sweden 2 Aerospace Mechatronics Group, University of Toronto Institute for Aerospace Studies, Toronto, ON M3H 5T6, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-416-946-3357 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Featured Application: Design, fabrication, testing, launch and operation of a particular CubeSat are detailed, as a reference for prospective developers of CubeSat missions. Abstract: The current success rate of CubeSat missions, particularly for first-time developers, may discourage non-profit organizations to start new projects. CubeSat development teams may not be able to dedicate the resources that are necessary to maintain Quality Assurance as it is performed for the reliable conventional satellite projects. This paper discusses the structured life-cycle of a CubeSat project, using as a reference the authors’ recent experience of developing and operating a 2U CubeSat, called qbee50-LTU-OC, as part of the QB50 mission. This paper also provides a critique of some of the current poor practices and methodologies while carrying out CubeSat projects. Keywords: CubeSat; miniaturized satellite; nanosatellite; small satellite development 1. Introduction There have been nearly 1000 CubeSats launched to the orbit since the inception of the concept in 2000 [1]. An up-to-date statistics of CubeSat missions can be found in Reference [2]. A summary of CubeSat missions up to 2016 can also be found in Reference [3]. -

Space Station Freedom. a Foothold on the Future. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 939 SE 050 885 AUTHOR David, Leonard TITLE Space Station Freedom. A Foothold on the Future. INSTITUTION National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC. Office of Space Sta.:Ion. REPORT NO NP-107/10-88 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 49p.; Colored photographs and drawings may not reproduce well. PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Technology; Engineering Technology; Planning; *Satellites (Aerospace); Science Materials; *Science Programs; *Scientific Research; *Space Exploration; *Space Sciences IDENTIFIERS *Space Station ABSTRACT This booklet describes the planning of the space station program. Sections included are: (1) "Introduction"; (2) "A New Era Begins" (discussing scientific experiments on the space station); (3) "Living in Space";(4) "Dreams Fulfilled" (summarizing the history of the space station development, including the skylab and shuttle); (5) "Building a Way Station to Worlds Beyond" (illustrating an approach to building the space station); (6) ''Orbital Mechanics" (discussing the maneuverability of the space station, including robotic application);(7) "Evolving with Versatility" (describing blueprints for expanding a space station); and (8) "Foothold on the Future" (discussing the future plans of the space station program). (YP) **************************************-******************************* * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. *********************************************************************A* -

Handbook for New Actors in Space Secure World Foundation

H SECURE WORLD FOUNDATION ANDBOOK HANDBOOK FOR NEW ACTORS IN SPACE SECURE WORLD FOUNDATION Space is rapidly changing. Every year, more numerous F and more diverse actors embark on increasingly novel, innovative, and disruptive ventures in outer space. They are OR HANDBOOK FOR joining the more than 70 states, commercial companies, N and international organizations currently operating over 1,500 satellites in Earth orbit. EW A NEW ACTORS The prospects are bright; accessing and exploring outer space now require less capital investment, less time, and CTORS fewer people than ever before. However, this rapid pace of IN SPACE growth and change exists in a complex landscape of legal, regulatory, political, technical, and administrative issues. New actors in space face a steep learning curve and will I stress existing institutions and governance frameworks. N Additionally, the inherently difficult and fragile nature of S the space environment means that accidents or mistakes in PACE space might affect us all. In considering the great possibilities for growth and innovation, and in light of the myriad and interlinked challenges new space activities will confront, the Secure World Foundation offers this Handbook for New Actors in Space in the hopes that it will assist all aspiring new entrants—whether governmental or non-governmental— in planning and conducting space activities in a safe and sustainable manner. 2017 EDITION 2017 Edition ISBN 978-0-692-45413-8 90000> | 1 9 780692 454138 2 | Handbook for New Actors in Space Secure World Foundation Handbook for New Actors in Space Edited by Christopher D. Johnson Nothing contained in this book is to be considered as rendering legal advice for specific cases, and readers are responsible for obtaining such advice from their legal counsel.