Disparate Impact and Voting Rights: How Objections to Impact-Based Claims Prevent Plaintiffs from Prevailing in Cases Challenging New Forms of Disenfranchisement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

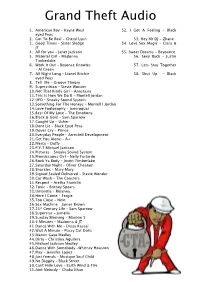

GTA Song List.Pages

Grand Theft Audio 1. American Boy – Kayne West 52. I Got A Feeling – Black eyed Peas 2. Got To Be Real – Cheryl Lynn 53. Hey Mr DJ - Zhane 3. Good Times – Sister Sledge 54. Love Sex Magic – Ciara & JT 4. All for you – Janet Jackson 55. Sweet Dreams - Beyounce 5. Material Girl – Madonna 56. Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake 6. Work It Out – Beyonce Knowles 57. Lets Stay Together – Al Green 7. All Night Long – Lionel Ritchie 58. Shut Up - Black eyed Peas 8. Tell Me – Groove Theory 9. Superstition – Stevie Wonder 10.Not That Kinda Girl – Anastasia 11.This Is How We Do It – Montell Jordan 12.UFO – Sneaky Sound System 13.Something For The Honeys – Montell l Jordan 14.Love Foolosophy – Jamiroquai 15.Best Of My Love – The Emotions 16.Black & Gold – Sam Sparrow 17.Caught Up – Usher 18.Dont Lie – Black Eyed Peas 19.Doves Cry – Prince 20.Everyday People – Arrested Development 21.Get You Alone – A+ 22.Mercy – Dufy 23.P.Y.T Michael Jackson 24.Pictures – Sneaky Sound System 25.Promiscuous Girl – Nelly Furtardo 26.Rock Ya Body – Justin Timberlake 27.Saturday Night – Oliver Cheatam 28.Shackles – Mary Mary 29.Signed Sealed Delivered – Stevie Wonder 30.Car Wash – The Coasters 31.Respect – Aretha Franklin 32.Toxic – Britney Spears 33.Umbrella – Rhianna 34.Here I Come – Fergie 35.Too Close – Next 36.Sex Machine – James Brown 37.21st Century Life – Sam Sparrow 38.Superstar - Jamelia 39.Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 40.4 Minutes – Madonna & JT 41.Dance With Me – Dizzy Rascal 42.Wait A Minute – Pussy Cat Dolls 43.Marvin Gaye Medley 44.Dirty – Christina Aguilera 45.Michael Jackson Medley 46.Dance With Somebody –Whitney Houston 47.Play – Jennifer Lopez 48.Just friends – Musique Soul Child 49.No Diggity – Black Street 50.Cant Hide Love – Earth Wind & Fire 51.Aint Nobody – Chaka Khan. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

NOW WAP's WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted By: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006

NOW WAP'S WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted by: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006 EMI Music UK puts pop stars in your pocket with launch of mobile music store wap.the-raft.com bringing together music downloads, ringtones & videos from EMI Records, Virgin Records, Parlophone, Angel and Catalogue - http://wapinfo.the-raft.com Calling all music fans… Fancy going home with a Brit tonight? EMI Music UK extends ‘The Raft’ online music store from web to mobile with the launch of its mobile music site (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). By texting ‘GO RAFT’ to 85080 (free text from all networks), music lovers will be able to access official artist news, breaking tour dates, music downloads and video, competitions and artist approved ringtones and realtones. And if you’ve got a bit of a creative urge yourself, you’ll be able to customise your own tracks by adding beats or special features to turn them into personalised ringtones (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). Be the envy of all your friends with your totally exclusive ringtones! You’ll be kept up to date with the latest news and featured artist areas which include Artist A-Zs and weekly competitions in anyone of the following categories; pop, urban, dance, jazz and rock. Wap.the-raft.com (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com) will also host the UK top 10 ringtones plus specialist charts like alternative and Bollywood. Competitions include money-can’t-buy exclusive artist merchandise plus album collections—such as the Brits collection; a bumper hamper of Brits-nominated albums Wap.the-raft.com provides something for every music fan—in an easy-to-find mobile music format. -

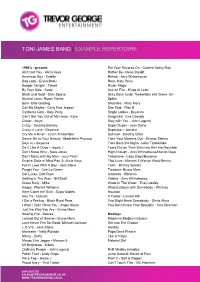

Toni James Band | Example Repertoire

TONI JAMES BAND | EXAMPLE REPERTOIRE 1990’s - present Put Your Records On - Corrine Bailey Ray Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys Rather Be- Clean Bandit American Boy - Estelle Rehab - Amy Whinehouse Bag Lady - Eryka Badu Roar- Katy Perry Boogie Tonight - Tweet Rude- Magic By Your Side - Sade Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Sexy Back Justin Timberlake into Grove Jet - Blurred Lines- Robin Thicke Spiller Burn- Ellie Golding Shackles - Mary Mary Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepson She Said - Plan B California Girls - Katy Perry Single Ladies - Beyonce Can’t Get You Out of My Head - Kylie Song Bird - Eva Cassidy Closer - Neyo Stay with You - John Legend Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Super Duper - Joss Stone Crazy in Love - Beyonce Superstar - Jamelia Cry Me A River - Justin Timberlake Survivor - Destiny Child Dance Me to Your Beauty - Madeleine Peyroux Take Your Mamma Out - Scissor Sisters Deja vu - Beyonce Take Back the Night- Justin Timberlake Do It Like A Dude - Jessie J Tears Dry on Their Own into Ain’t No Mountain Don’t Know Why - Nora Jones High Enough - Amy Whinehouse/Marvin Gaye Don’t Mess with My Man - Lucy Pearl Telephone - Lady Gaga/Beyonce Empire State of Mind Part 2- Alicia Keys This Love - Maroon 5 (Kanye West Remix) Fell in Love With A Boy - Joss Stone Toxic - Britney Spears Forget You - Cee Lo Green Treasure- Bruno Mars Get Lucky- Daft Punk Umbrella - Rihanna Getting in The Way - Gill Scott Valerie - Amy Whinehouse Grace Kelly - Mika Wade in The Water - Eva Cassidy Happy- Pharrell Williams Wanna Dance with Somebody -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Jack Holden Premiere, Avid and Afterfx Editor

Jack Holden Premiere, Avid and AfterFX Editor Profile Jack is a content-driven fast editor who prides himself on blending technical knowledge with a drive to create television that informs and surprises. He is as comfortable working on flagship factual series such as "How the Universe Works" as he is on news/current affairs "The Listening Post" and short form pieces which require taking a programme from brief to clocked TX master. As well as Avid, he has comprehensive knowledge of Premiere Pro and FCP, and experience with After Effects. He also is an experienced camera operator and drone owner/operator. Long Form “Auschwitz Untold: In Colour” 1 x 86min. Focusing on the incredible stories of 12 concentration camp survivors, this film will be broadcast as part of the commemorations for the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 1945. Directed by BAFTA-winner David Shulman. Fulwell 73 for History Channel & Channel 4 “The Tonight Show” 1 x 30min current affairs show. Seven billion pounds has already been spent on Britain's controversial North-South high-speed rail link, but will the project be abandoned? ITN for ITV “Dispatches: The Prince and the Paedophile” 1 x 30min current affairs documentary investigating the links between convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein and Prince Andrew. Brite Spark for Channel 4 “One Hour that Changed the World: Moon Landing” 1 x 60min. Documentary celebrating the historic 50th Anniversary of Apollo 11 starting with the iconic moment and rewinding back one hour, minute by minute with real ticking clock tension. Through archive footage and interviews the viewer is immersed in the high stakes environment, revealing the hidden history of how the heroic astronauts were on a knife edge between triumph or tragedy. -

Jamelia Feat. Rah Digga - Jamelia Feat

Jamelia Bout mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Bout Country: UK Released: 2003 Style: RnB/Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1845 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1258 mb WMA version RAR size: 1167 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 180 Other Formats: VOX DTS WMA MP4 AU MOD APE Tracklist Hide Credits Bout (Single Edit) 1 Backing Vocals – Jamelia, Sammi JayFeaturing – Rah DiggaKeyboards – C Swing*Mixed By – Manny Maroquin* For You Backing Vocals – Amber Rene, JameliaCello – Oliver Krauss*, Sarah WilsonPiano, Keyboards, 2 Bass – C Swing*Viola – Katherine Shave, Reiad ChibahViolin – Anna Giddey, Antonia Fuchs, Caroline Clarke, Joanna Lee Girlfriend Backing Vocals – Amber Rene, Belle Montenegro, JameliaCello – Oliver Krauss*, Sarah 3 WilsonKeyboards – C Swing*Viola – Katherine Shave, Reiad ChibahViolin – Anna Giddey, Antonia Fuchs, Caroline Clarke, Joanna Lee Video Bout Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – EMI Records Ltd. Manufactured By – EMI Uden Credits Written-By – Emmanuel , Jamelia Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: Bel Biem Matrix / Runout: 5521140 @ 1 1-1-3 NL Mastering SID Code: IFPI L047 Mould SID Code: ifpi 1517 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Jamelia Jamelia Featuring Rah 12RDJY 6597 Featuring Rah Digga - Bout (Remixes) Parlophone 12RDJY 6597 UK 2003 Digga (12", Promo) none Jamelia Bout (Acetate, 12") Parlophone none UK 2003 Jamelia Jamelia Featuring Rah CDRDJ 6597 Featuring Rah Digga - Bout (CDr, Single, Parlophone CDRDJ 6597 UK 2003 Digga Promo) Jamelia Feat. Rah Digga - Jamelia Feat. Not On Label Bout (12", S/Sided, W/Lbl, Parlophone Not On Label UK 2003 Rah Digga 180) 12RDJX 6597 Jamelia Bout (12", Promo) Parlophone 12RDJX 6597 UK 2003 Related Music albums to Bout by Jamelia Jamelia - Something About You Jamelia - Money (Remix) Jamelia - Thank You Jamelia - Superstar Jamelia - Beware Of The Dog Jamelia - Drama Jamelia - Bout Jamelia - Money. -

Movie Catalog Page 66

© 2018 Universal City Studios Productions LLLP and Amblin Entertainment, Inc. All Rights Reserved © 2018 Disney/Pixar Pictures Paramount © © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. © Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc. © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Bleecker Street Media, LLC © 2018 STX Entertainment Introducing DREAMWORKS ANIMATION CONTENT Page 46 NEW ARTS On-Board AND CULTURE PROGRAMMING Movie Catalog Page 66 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 www.onboardmovies.com 1.877.660.7245 TABLE OF CONTENTS COMING SOON New Releases ...........................................................2–41 DREAMWORKS ANIMATION HBO .................................................................................42-45 DreamWorks Animation .............................46-47 Contact We are excited to announce that On-Board Short Programming Movies will have exclusive rights to DreamWorks Trending TV ...................................................................... 48-50 Animation titles effectiveOctober 2018! US! Lifestyle Programming Food Network ......................................................................... 51 Cooking Channel .................................................................... 52 Travel Channel ........................................................................53 Visit us online at DIY Network ...........................................................................54 www.onboardmovies.com Plan on sharing these top hits and animated classics — as well as all HGTV ....................................................................................... -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

21 June 2004 CHART #1413 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums They Can't Take That Away She Glows One Road UNDER MY SKIN 1 Ben Lummis 21 Zed 1 Ben Lummis 21 Avril Lavigne Last week 1 / 6 weeks Platinum x4 / BMG Last week 27 / 5 weeks Universal Last week 0 / 1 weeks Platinum x2 / BMG Last week 20 / 4 weeks BMG Burn HEY MAMA Confessions SHREK 2 OST 2 Usher 22 Black Eyed Peas 2 Usher 22 Various Last week 32 / 3 weeks BMG Last week 26 / 16 weeks Gold x1 / Universal Last week 1 / 9 weeks Platinum x1 / BMG Last week 0 / 1 weeks Universal I Don't Wanna Know Left Outside Alone Opera Band A Grand Don't Come For Free 3 Mario Winans 23 Anastacia 3 Amici Forever 23 The Streets Last week 4 / 5 weeks Universal Last week 23 / 4 weeks Sony Music Last week 2 / 17 weeks Platinum x1 / BMG Last week 24 / 4 weeks WEA/Warner Fools Love What About Me? To The 5 Boroughs Franz Ferdinand 4 Misfits Of Science 24 Shannon Noll 4 Beastie Boys 24 Franz Ferdinand Last week 2 / 4 weeks Hoof/BMG Last week 21 / 19 weeks BMG Last week 0 / 1 weeks Gold x1 / Capitol/EMI Last week 23 / 8 weeks Gold x1 / Sony Music Yeah I BELIEVE IN A THING CALLED LO... Greatest Hits Sunrise Over Sea 5 Usher feat. Lil Jon & Ludacris 25 The Darkness 5 Guns N Roses 25 John Butler Trio Last week 3 / 13 weeks Platinum x1 / BMG Last week 22 / 13 weeks EW/Warner Last week 3 / 13 weeks Platinum x3 / Universal Last week 25 / 3 weeks Capitol/EMI Roses I MISS YOU Home, Land And Sea Greatest Hits 6 Outkast 26 Blink 182 6 TrinityRoots 26 Atomic Kitten Last week 5 / 6 weeks BMG Last week 20 / 16 weeks Universal -

Policing Under Disability Law

Stanford Law Review Volume 73 June 2021 ARTICLE Policing Under Disability Law Jamelia N. Morgan* Abstract. In recent years, there has been increased attention to the problem of police violence against disabled people. Disabled people are overrepresented in police killings and, in a number of cities, police use-of-force incidents. Further, though police violence dominates the discussion of policing, disabled people also disproportionately experience more ordinary forms of policing that can lead to police violence. For example, disabled people, particularly those with untreated psychiatric disabilities, are vulnerable to policing even in medical facilities—the very places they seek to access care. Many are also arrested pursuant to aggressive enforcement policies aimed at removing so-called unwanted persons or regulating those labeled disruptive or disorderly. Though they pose no risk of physical harm, some are arrested and taken to jail, at times simply because they have no place else to go. This Article centers disability theory as a lens for understanding the problems of policing and police violence as they impact disabled people. In doing so, the Article examines how federal disability law addresses these ongoing problems. Disabled plaintiffs have alleged disability discrimination and challenged policing and police violence under both Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, another federal disability law and the precursor to the ADA. The Supreme Court has yet to decide whether Title II of the ADA applies to arrests, and federal appellate courts are split on whether and to what extent Title II’s antidiscrimination provisions apply to street encounters and arrests. -

Toniah-Bio.Pdf

Director Cirkus summarum 16 Cirkus Summarum 18 Tv shows Popstars DK judge/2001 Popstars DK judge/2002 Popstars UK choreographer for the show/2002 Popstars: The Rivals ITV – September to December So you think you can dance judge/choreographer/2006 So you think you can dance choreographer 2008 X-Factor DK bootcamp Judge w Soulshock X-Factor DK 2010 Choreographer for Soulshock X-Factor DK 2011 Choreographer X-Factor DK 2012 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2013 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2014 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2015 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2016 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2017 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2018 Creative director/choreographer X-Factor DK 2019 Creative director/choreographer Kim Cesarion X-Factor final/ choreographer Omi X-Factor final/ choreographer Skjulte Stjerner DR Choreographer Vild m dans(Dance w the Stars) Choreographer opening/2009 Vild m dans/Dance w the Stars Choreographer opening and final/2011 Vild m dans/Dance w the Stars Choreographer opening and final/2012 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer opening/final/Anniversary/2013 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer opening/final 2014 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer opening/final 2015 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer opening/final 2016 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer opening/final 2017 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer/ creative director 2018 Vild m dans(Dancing w the Stars) Choreographer/ creative -

2021 Public Interest Careers

Public Interest Careers Introduction to Public Interest Careers • 2015-2016 YALE LAW SCHOOL • CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE • NEW HAVEN, CT yale law school • career development office www.law.yale.edu/cdo *Please note: Some sections of this public guide have been removed due to their proprietary nature. Table of Contents Index of Alumni Narratives Chapter 1 A Career in Public Interest Law A. Public Interest Settings 1. Public Interest Organizations 2. Government 3. Law Firms B. Most Frequently Asked Public Interest Questions Chapter 2 Public Interest Employment Strategies A. The Job Search Process 1. Self-Assessment 2. Credentials 3. Timing 4. Résumés and Cover Letters 5. Interviews 6. Employer Follow Up 7. Meeting the Challenges of a Fluctuating Market B. Suggested Timetables of Job Search Activities Chapter 3 Yale Support for Public Interest Careers A. CDO Public Interest Resources 1. CDO Publications 2. Educational and Mentor in Residence Programs 3. Public Interest Employer Information 4. Student and Alumni Networking 5. Online Resources 6. Events 7. Fellowship Information 8. Pro Bono Information B. Other YLS Public Interest Resources 1. Student Public Interest Organizations 2. Clinical Programs 3. Externships 4. Law Journals 5. Robert M. Cover Public Interest Retreat 6. Arthur Liman Public Interest Center 7. Schell Center for International Human Rights 8. *Please note: Some sections of this public guide have been removed. C. Yale Law School Funding Programs 1. The Job Search 2. Summer Funding 3. Term Funding 4. Postgraduate Fellowships 5. Educational Loan Repayment through COAP Yale Law School Career Development Office D. Yale University Funding Programs 1. Summer Funding 2.