Policing Under Disability Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Step Off the Road, and Let the Dead Pass By

191 Step Off the Road, and Let the Dead Pass By Le ceremony of paying homage to our honored need for a special memorial day, except as such an dead has been held annually on the Sunday closest to occasion is used to strengthen us in our resolves to September 29, the day that the lOOth Infantry Battalion live in a manner worthy of the dead, and as such an first entered combat in Italy in 1943 and suffered its first occasion serves to remind the world around us of the casualties. Through the years, we have been blessed with splendid achievements of the Americans of Japanese the eloquence of many distinguished speakers at these ancestry. annual memorial services, but rarely has the evocative All of us here present have reason to be thank power of speech so captured our souls as the address ful for what our dead have done. Because of such given by Israel Yost, our frontline chaplain, at the 1947 soldiers the war was kept away from America; service. That speech is reproduced below. because of these men our homes were not invaded, nor our loved ones endangered, nor our property Comrades and friends and parents: destroyed. We who were over there have seen what I regret that I am not able to address you war does to a country; because of the courage of our parents of our fallen comrades in the language with comrades, even unto death, we at home have been which you are most familiar. If I could I would glad spared such ravages of war. -

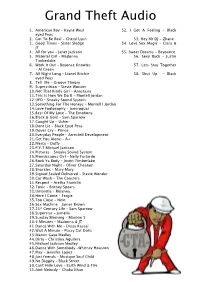

GTA Song List.Pages

Grand Theft Audio 1. American Boy – Kayne West 52. I Got A Feeling – Black eyed Peas 2. Got To Be Real – Cheryl Lynn 53. Hey Mr DJ - Zhane 3. Good Times – Sister Sledge 54. Love Sex Magic – Ciara & JT 4. All for you – Janet Jackson 55. Sweet Dreams - Beyounce 5. Material Girl – Madonna 56. Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake 6. Work It Out – Beyonce Knowles 57. Lets Stay Together – Al Green 7. All Night Long – Lionel Ritchie 58. Shut Up - Black eyed Peas 8. Tell Me – Groove Theory 9. Superstition – Stevie Wonder 10.Not That Kinda Girl – Anastasia 11.This Is How We Do It – Montell Jordan 12.UFO – Sneaky Sound System 13.Something For The Honeys – Montell l Jordan 14.Love Foolosophy – Jamiroquai 15.Best Of My Love – The Emotions 16.Black & Gold – Sam Sparrow 17.Caught Up – Usher 18.Dont Lie – Black Eyed Peas 19.Doves Cry – Prince 20.Everyday People – Arrested Development 21.Get You Alone – A+ 22.Mercy – Dufy 23.P.Y.T Michael Jackson 24.Pictures – Sneaky Sound System 25.Promiscuous Girl – Nelly Furtardo 26.Rock Ya Body – Justin Timberlake 27.Saturday Night – Oliver Cheatam 28.Shackles – Mary Mary 29.Signed Sealed Delivered – Stevie Wonder 30.Car Wash – The Coasters 31.Respect – Aretha Franklin 32.Toxic – Britney Spears 33.Umbrella – Rhianna 34.Here I Come – Fergie 35.Too Close – Next 36.Sex Machine – James Brown 37.21st Century Life – Sam Sparrow 38.Superstar - Jamelia 39.Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 40.4 Minutes – Madonna & JT 41.Dance With Me – Dizzy Rascal 42.Wait A Minute – Pussy Cat Dolls 43.Marvin Gaye Medley 44.Dirty – Christina Aguilera 45.Michael Jackson Medley 46.Dance With Somebody –Whitney Houston 47.Play – Jennifer Lopez 48.Just friends – Musique Soul Child 49.No Diggity – Black Street 50.Cant Hide Love – Earth Wind & Fire 51.Aint Nobody – Chaka Khan. -

Survey: Both Democrats and GOP Love 'This Is Us,' 'Game of Thrones'

Survey: Both Democrats and GOP love 'This Is Us,' 'Game of Thrones' BY JUDY KURTZ - 03/03/20 © Courtesy of HBO The country may be more politically polarized than ever, but there are at least a couple things that both Democrats and Republicans agree on: They dig "This is Us" and "Game of Thrones." The NBC drama and former HBO fantasy series were some of the top picks on both sides of the aisle, according to a recent survey from E-Poll Market Research. Fifty-five percent of Democrats counted "This is Us" as their fave broadcast TV show, along with 68 percent of Republicans. Fifty-two percent of Democrats and 47 percent of Republicans surveyed also listed "Chicago Med" as one of their top TV picks. Other popular choices among Democrats included "Supernatural," Fox's "9-1-1" and "The Rookie," while Republicans said they delighted in "Grey's Anatomy," "Last Man Standing" and Chicago PD." The two parties had more than half of the top 20 TV shows in common, but there were a few notable differences among their boob tube choices. The results show that, of the Americans surveyed, Democrats prefer getting more laughs from their small screen fare, picking seven sitcoms as their favorites, compared to the GOP respondents' three comedy shows. A separate survey of top streaming and cable shows found that Democrats preferred Starz's "Power," with 63 percent of those surveyed naming it as their favored show, and "Game of Thrones," with 51 percent. Sixty-seven percent of Republicans named "Game of Thrones" — which ended its eight-season run last year — as their No. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Chapter 7 Interact with History

The port of New Orleans, Louisiana, a major center for the cotton trade 1820 James Monroe is 1817 reelected president. 1824 John Construction 1819 U.S. Quincy Adams begins on the acquires Florida 1820 Congress agrees to is elected Erie Canal. from Spain. the Missouri Compromise. president. USA 1815 WORLD 1815 1820 1825 1815 Napoleon 1819 Simón 1822 Freed 1824 is defeated at Bolívar becomes U.S. slaves Mexico Waterloo. president of found Liberia on becomes Colombia. the west coast a republic. of Africa. 210 CHAPTER 7 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1828. You are a senator from a Southern state. Congress has just passed a high tax on imported cloth and iron in order to protect Northern industry. The tax will raise the cost of these goods in the South and will cause Britain to buy less cotton. Southern states hope to nullify, or cancel, such federal laws that they consider unfair. Would you support the federal or state government? Examine the Issues • What might happen if some states enforce laws and others don't? • How can Congress address the needs of different states? •What does it mean to be a nation? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 7 links for more information about Balancing Nationalism and Sectionalism. 1838 1828 Removal of Andrew 1836 Martin the Cherokee 1840 William Jackson 1832 Andrew Van Buren along the Henry Harrison is elected Jackson is elected Trail of Tears is elected president. is reelected. president. begins. president. 1830 1835 1840 1830 France 1833 British 1837 Victoria 1839 Opium invades Algeria. -

Chapter 5 the Americans.Pdf

Washington (on the far right) addressing the Constitutional Congress 1785 New York state outlaws slavery. 1784 Russians found 1785 The Treaty 1781 The Articles of 1783 The Treaty of colony in Alaska. of Hopewell Confederation, which Paris at the end of concerning John Dickinson helped the Revolutionary War 1784 Spain closes the Native American write five years earli- recognizes United Mississippi River to lands er, go into effect. States independence. American commerce. is signed. USA 1782 1784 WORLD 1782 1784 1781 Joseph II 1782 Rama I 1783 Russia annexes 1785 Jean-Pierre allows religious founds a new the Crimean Peninsula. Blanchard and toleration in Austria. dynasty in Siam, John Jeffries with Bangkok 1783 Ludwig van cross the English as the capital. Beethoven’s first works Channel in a are published. balloon. 130 CHAPTER 5 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1787. You have recently helped your fellow patriots overthrow decades of oppressive British rule. However, it is easier to destroy an old system of government than to create a new one. In a world of kings and tyrants, your new republic struggles to find its place. How much power should the national government have? Examine the Issues • Which should have more power—the states or the national government? • How can the new nation avoid a return to tyranny? • How can the rights of all people be protected? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 5 links for more information about Shaping a New Nation. 1786 Daniel Shays leads a rebellion of farmers in Massachusetts. 1786 The Annapolis Convention is held. -

NOW WAP's WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted By: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006

NOW WAP'S WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted by: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006 EMI Music UK puts pop stars in your pocket with launch of mobile music store wap.the-raft.com bringing together music downloads, ringtones & videos from EMI Records, Virgin Records, Parlophone, Angel and Catalogue - http://wapinfo.the-raft.com Calling all music fans… Fancy going home with a Brit tonight? EMI Music UK extends ‘The Raft’ online music store from web to mobile with the launch of its mobile music site (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). By texting ‘GO RAFT’ to 85080 (free text from all networks), music lovers will be able to access official artist news, breaking tour dates, music downloads and video, competitions and artist approved ringtones and realtones. And if you’ve got a bit of a creative urge yourself, you’ll be able to customise your own tracks by adding beats or special features to turn them into personalised ringtones (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). Be the envy of all your friends with your totally exclusive ringtones! You’ll be kept up to date with the latest news and featured artist areas which include Artist A-Zs and weekly competitions in anyone of the following categories; pop, urban, dance, jazz and rock. Wap.the-raft.com (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com) will also host the UK top 10 ringtones plus specialist charts like alternative and Bollywood. Competitions include money-can’t-buy exclusive artist merchandise plus album collections—such as the Brits collection; a bumper hamper of Brits-nominated albums Wap.the-raft.com provides something for every music fan—in an easy-to-find mobile music format. -

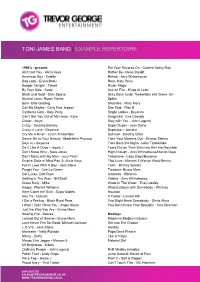

Toni James Band | Example Repertoire

TONI JAMES BAND | EXAMPLE REPERTOIRE 1990’s - present Put Your Records On - Corrine Bailey Ray Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys Rather Be- Clean Bandit American Boy - Estelle Rehab - Amy Whinehouse Bag Lady - Eryka Badu Roar- Katy Perry Boogie Tonight - Tweet Rude- Magic By Your Side - Sade Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Sexy Back Justin Timberlake into Grove Jet - Blurred Lines- Robin Thicke Spiller Burn- Ellie Golding Shackles - Mary Mary Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepson She Said - Plan B California Girls - Katy Perry Single Ladies - Beyonce Can’t Get You Out of My Head - Kylie Song Bird - Eva Cassidy Closer - Neyo Stay with You - John Legend Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Super Duper - Joss Stone Crazy in Love - Beyonce Superstar - Jamelia Cry Me A River - Justin Timberlake Survivor - Destiny Child Dance Me to Your Beauty - Madeleine Peyroux Take Your Mamma Out - Scissor Sisters Deja vu - Beyonce Take Back the Night- Justin Timberlake Do It Like A Dude - Jessie J Tears Dry on Their Own into Ain’t No Mountain Don’t Know Why - Nora Jones High Enough - Amy Whinehouse/Marvin Gaye Don’t Mess with My Man - Lucy Pearl Telephone - Lady Gaga/Beyonce Empire State of Mind Part 2- Alicia Keys This Love - Maroon 5 (Kanye West Remix) Fell in Love With A Boy - Joss Stone Toxic - Britney Spears Forget You - Cee Lo Green Treasure- Bruno Mars Get Lucky- Daft Punk Umbrella - Rihanna Getting in The Way - Gill Scott Valerie - Amy Whinehouse Grace Kelly - Mika Wade in The Water - Eva Cassidy Happy- Pharrell Williams Wanna Dance with Somebody -

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013

War of 1812 Booklist Be Informed • Be Entertained 2013 The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and Great Britain from June 18, 1812 through February 18, 1815, in Virginia, Maryland, along the Canadian border, the western frontier, the Gulf Coast, and through naval engagements in the Great Lakes and the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In the United States frustrations mounted over British maritime policies, the impressments of Americans into British naval service, the failure of the British to withdraw from American territory along the Great Lakes, their backing of Indians on the frontiers, and their unwillingness to sign commercial agreements favorable to the United States. Thus the United States declared war with Great Britain on June 18, 1812. It ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814, although word of the treaty did not reach America until after the January 8, 1815 Battle of New Orleans. An estimated 70,000 Virginians served during the war. There were some 73 armed encounters with the British that took place in Virginia during the war, and Virginians actively fought in Maryland, Virginia, and Ohio and in naval engagements. The nation’s capitol, strategically located off the Chesapeake Bay, was a prime target for the British, and the coast of Virginia figured prominently in the Atlantic theatre of operations. The War of 1812 helped forge a national identity among the American states and laid the groundwork for a national system of homeland defense and a professional military. For Canadians it also forged a national identity, but as proud British subjects defending their homes against southern invaders. -

The Americans

UUNNIITT AmericanAmerican BeginningsBeginnings CHAPTER 1 Three Worlds Meet toto 17831783 Beginnings to 1506 CHAPTER 2 The American Colonies Emerge 1492–1681 CHAPTER 3 The Colonies Come of Age 1650–1760 CHAPTER 4 The War for Independence 1768–1783 UNIT PROJECT Letter to the Editor As you read Unit 1, look for an issue that interests you, such as the effect of colonization on Native Americans or the rights of American colonists. Write a letter to the editor in which you explain your views. Your letter should include reasons and facts. The Landing of the Pilgrims, by Samuel Bartoll (1825) Unit 1 1 View of Boston, around 1764 1693 The College of William and 1651 English Parliament 1686 James II creates Mary is chartered passes first of the the Dominion of New in Williamsburg, Navigation Acts. England. Virginia. AMERICAS 1650 1660 1670 1680 1690 1700 WORLD 1652 Dutch settlers 1660 The English 1688 In England the Glorious establish Cape Town monarchy is restored Revolution establishes the in South Africa. when Charles II supremacy of Parliament. returns from exile. 64 CHAPTER 3 INTERACT WITH HISTORY The year is 1750. As a hard-working young colonist, you are proud of the prosperity of your new homeland. However, you are also troubled by the inequalities around you—inequalities between the colonies and Britain, between rich and poor, between men and women, and between free and enslaved. How can the colonies achieve equality and freedom? Examine the Issues • Can prosperity be achieved without exploiting or enslaving others? • What does freedom mean, beyond the right to make money without government interference? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 3 links for more information related to The Colonies Come of Age. -

The First Americans the 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park

United States Cryptologic History The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park Special series | Volume 12 | 2016 Center for Cryptologic History David J. Sherman is Associate Director for Policy and Records at the National Security Agency. A graduate of Duke University, he holds a doctorate in Slavic Studies from Cornell University, where he taught for three years. He also is a graduate of the CAPSTONE General/Flag Officer Course at the National Defense University, the Intelligence Community Senior Leadership Program, and the Alexander S. Pushkin Institute of the Russian Language in Moscow. He has served as Associate Dean for Academic Programs at the National War College and while there taught courses on strategy, inter- national relations, and intelligence. Among his other government assignments include ones as NSA’s representative to the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council, and on the staff of the National Economic Council. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other US government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (Top) Navy Department building, with Washington Monument in center distance, 1918 or 1919; (bottom) Bletchley Park mansion, headquarters of UK codebreaking, 1939 UNITED STATES CRYPTOLOGIC HISTORY The First Americans The 1941 US Codebreaking Mission to Bletchley Park David Sherman National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History 2016 Second Printing Contents Foreword ................................................................................ -

Declaration of Jihad Against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holiest Sites

(Document page 1) Declaration of Jihad Against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holiest Sites. (Expel the infidels from the Arab Peninsula). A message from Usamah Bin Muhammad Bin Ladin Unto his Muslim brethren all over the world generally and the Arabian Peninsula specifically. Praise be to Allah, we seek His help and ask for His pardon. We take refuge in Allah from our wrongs and bad deeds. Whom ever Allah has guided will not be misled, and who ever has been misled, will never be guided. I bear witness that there is no God but Allah, no associate with Him and I bear witness that Muhammad is His servant and Messenger. {O ye who believe! Fear Allah as He should be feared, and die not except in a state of Islam}, {O mankind! Reverence your Guardian-Lord, Who created you from a single Person, created of like nature, His mate, and from them twain scattered (like seeds) countless men and women-fear Allah, through Whom ye demand your mutual (rights), and (reverence) the wombs (that bore you): for Allah ever watches over you}. {O ye who your conduct whole and sound and forgive you your sins: He who obeys Allah and His messenger has already attained the highest achievement}. Praise be to Allah Who said: {I only desire (your) betterment to the best of my power; and my success (in my task)}. [Hud:88]. Praise be to Allah Who said: {Ye are the best of peoples, evolved for mankind, enjoying what is right, forbidding what is wrong, and believing in Allah}.